Education

My Late Father Was a Great Teacher. He Wouldn’t Last a Week in the Modern Classroom.

All teachers have a hope of how they will be perceived by the students sitting in their classrooms. Too many of us today want to be perceived as accommodating and nice, compassionate and endlessly empathetic.

My father passed away a few weeks ago. He had spent his entire working life teaching junior high and high school students. Most communities in our country possess a few teachers of my father’s ilk, educators who are considered local celebrities—the type who can rarely enter a restaurant or movie theatre without encountering at least a smattering of former students or thankful parents.

Often, teacher-celebrities teach for decades. They oversee successful academic, athletic, or artistic programs. They might even win a teaching award or two. But most of all, they are fondly remembered by their former students. They hear superlatives like, “You made a real difference in my life” or “I wouldn’t be where I am today without you.” They are localized versions of Jaime Escalante or non-fiction avatars of John Keating.

Still, I was overwhelmed by the volume of notes, e-mails, and letters I received from his former students, all painting a similar picture of my father: he was a tough teacher, a bit intimidating at first, but ultimately a man who helped generations of young people find their own paths in life. The letters were filled with powerful and colorful testimonials about his unwavering sense of purpose and ubiquitous passion.

One of the letters I received was from a former student who became both an ER doctor and an award-winning medical school instructor. Looking back on my father 35 years later, this is what he had to say:

Only through the natural course of time have I come to appreciate how he engaged his classroom, how he mastered the material he taught, and how he truly cared about his students. I now see his wisdom, humor, and devotion to his craft with a clarity I lacked at the time. His "tough love" approach, which seemed personal, mean, and unbearable at times to my immature 14-year-old brain, was exactly the inspiration and motivation I needed to push me to reach for my potential.

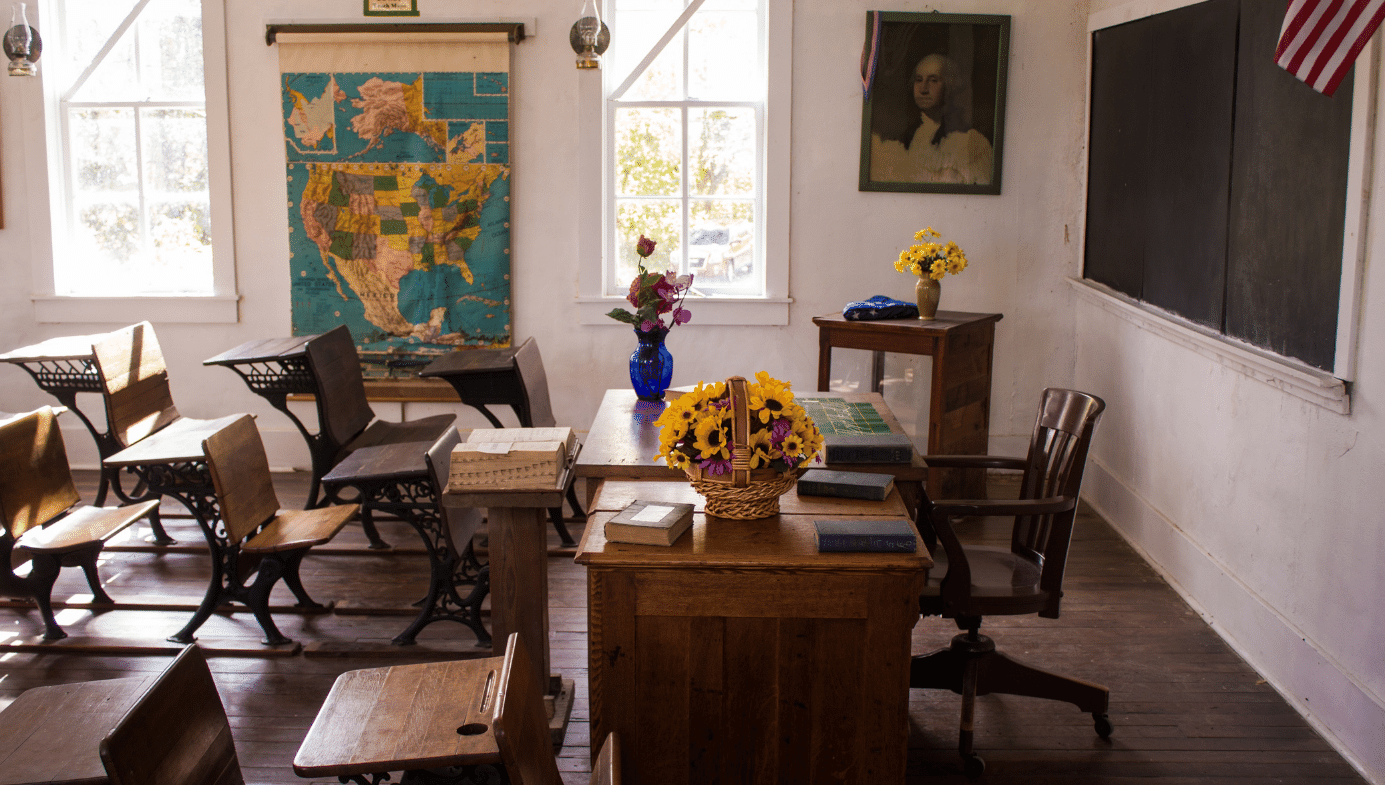

Here was a man who ardently believed in the Socratic method of teaching, walking up and down rows of desks, never allowing anyone to hide in a classroom crevice or sulk with proud indifference. Students eventually came to understand that his affection for them was intimately tied to his belief in their capacity to learn and achieve. After all, a good teacher doesn’t tolerate student ignorance or indifference.

And yet, my father would probably be appalled to learn that the Socratic method is woefully out of step with a generation of young people who find feelings—not facts, evidence, or knowledge—to be sovereign. Challenging a young person to defend the material they devour on TikTok, Instagram, or Twitter—and doing so in front of the entire class, mind you—would probably land him in a bit of hot water these days. Administrators would demand to know the learning objective to which his questioning was tied. Parents would complain about how “uncomfortable” their son or daughter now felt. Fellow teachers would counsel him, “Be careful. Let them think whatever they want to think.”

He never let students chew gum or even wear hats in class because a classroom is a serious place and serious places demand respectful behavior. If you were in his second period class (home room) you learned the proper cadence of the Pledge of Allegiance. “There is no comma after ‘nation’ and before ‘under God,’” he thundered at successive generations. He always respected those who didn’t say the Pledge for religious reasons but would probably be aghast at the blasé, nondescript platitudes offered up by modern students who can rarely articulate concrete reasons for sitting during the national anthem beyond avant-garde pieties about generalized “oppression” or “white supremacy.”

He taught short stories, essays, plays, and poetry if they were instructive about the human condition; he had too much regard for the transformative power of literature to ever use it as a political cudgel with which to insist upon different forms of “representation.” He never judged literature through a postmodern kaleidoscope of race, gender, or class. He simply asked if the reading was instructive about love or hope or death or dreams. Did it touch on vital and timeless human concerns? Did it connect a young mind to a mature aspiration or did it slightly transform the delicate fiber of youth into something resembling wisdom or fortitude?

I was actually a student in his class when I was a high school freshman in the early 1990s. I don’t remember him ever having to apologize for high standards. We had to learn 40 vocabulary words a week. He insisted on old school grammar lessons every Thursday and woe betide those who forgot their grammar books. He spent weeks teaching the history of the English language.

When I try to describe this course and his methods to my current students, the look on their faces sits somewhere between horror and relief. It raises a fascinating but disturbing question: how would my father appear to a modern professor in a chic school of education? How would he come across to the legions of professional development gurus selling the latest fads in education? What would he say to students—or to their parents—manipulating the 504-accommodation policy simply to win test retakes or extra time on exams? How would he process Adderall-addicted students popping pills before the final exam?

Or flip the question around: What would my father do the first time he was cursed at by a student and told by the principal to “have a classroom intervention” instead of writing a referral to the dean? How would he respond to student after student taking out their devices in the middle of class to check their texts, follow their feeds, or update their status? Would he accept that Socrates is a bully, high expectations are a sign of lacking empathy for students, Shakespeare is “problematic,” and grammar is “unnecessary?” I can’t imagine my father finding the humor in “becoming a meme.”

As great as he was, I’m not sure he would know how to teach students who are dogmatic about their skepticism and cocksure in their cynicism. In fact, in the weeks since his death, it has become painfully apparent that his entire storied teaching career stands as a totem juxtaposed to the central educational fiction of our time—chiefly, that teacher compassion is tantamount to an endless softening of standards, of letting things slide, or donning the chic accoutrements that attribute all poor behavior or subpar performance to “structural realities” or “systemic oppression.”

Compassion in the form of excuse-making is producing a generation of students who want the trophy without the excellence and the “A” without the effort. This is how you get a generation that thinks wealth is a birthright and high achievement can be accomplished on the cheap.

My father grew up in a shack. His father was an alcoholic, and his family moved from neighborhood to neighborhood in constant search of affordable housing because employment was never certain. He worked mightily to pull himself out of the squalor that defined his childhood. He enlisted in the military. He put himself through college. He worked while he earned a master’s degree. He put in the long hours to win the 1988 California Speech and Debate championship for the high school where he taught. He was a planner. He was gritty. He was painfully insecure. And no, he never expected anything to be easy.

He understood a truth about America that has been painfully forgotten in modern times: success—even the faintest whisper or morsel of it—requires colossal sacrifice. And yet, even when sacrifice and patience and pertinacity are emphatically practiced, still—still!—success can prove excruciatingly elusive. Just ask any aspiring writer.

My father taught the way he did because he recognized the unpleasant truth that the world only honors those who are willing to grind, drudge, and eek their way towards a goal, even a modest one. Want a good grade? Don’t miss class, pay attention, and put in hours of studying. Want to be praised? Do something that is genuinely praiseworthy. Or, to phrase it in the words of fellow high school teacher, Shane Trotter, author of the soon-to-be-released book Setting The Bar, “What we have is a system driven to create the illusion of education without the inconvenience of learning.”

Young Americans want the freedom that excuses indulgence, but not the freedom that demands self-reliance. They are mired in a moment in history where nihilism has become conventional wisdom and the traditional pillars of excellence—diligence, duty, dedication—are smugly transmogrified into relics of a bygone era. This is how we arrive at a place where students can retake tests as many times as they want to, a place where schools now have more than a dozen valedictorians every spring, a place where a student caught cheating during a test is likely defended rather than punished by his parent.

In this educational cosmos, my father would be an unwelcome alien. Or to be blunt, he would probably be seen as an unsympathetic, pugilistic, classroom “Boomer.” He would be woefully out of touch with an educational system that has tragically conflated the victory of a high GPA with the long-term aspiration of imbuing young Americans with the habits, values, and knowledge that would empower them to live meaningful and purpose-driven lives.

The notes about my father weren’t about test scores and college admission. They were about the universal aim of human flourishing. His former students flourished in their lives not because of my father’s compassion, but because of his inspiration.

All teachers have a hope of how they will be perceived by the students sitting in their classrooms. Too many of us today want to be perceived as accommodating and nice, compassionate and endlessly empathetic. We think we are doing our students a favor by marrying education with ease and academics with adoration. These students might like us in the moment, but trust me, when we die someday, they won’t remember much we ever did for them.