Education

The Problems with America's Best Teacher Training Programme

If there is one certainty within educational research, it is that there is no single distinct and best way to teach.

A question central to Plato’s Republic is “What should we teach our children?” Judging from the parents I’ve talked to, this question is not getting the consideration it deserves. Parroting a common conservative refrain regarding what some believe schools teach, a colleague referred to them as “liberal-producing factories.” Thankfully, that’s not quite the case. While the teaching profession as a whole leans left, most educators are aware of their bias and, with varying degrees of success, try to push against it. Unfortunately, this is not true of the programs that train the nation’s school staff.

I received a master’s degree in curriculum and instruction from the University of Wisconsin-Madison, one of the premier schools of education in the country, occasionally nudging out Columbia and Harvard for the top spot in U.S. News and World Report’s ranking of education programs. In reality, it was a series of graduate courses that featured various arts and crafts projects.

To their credit, the faculty seek to ameliorate legitimate and pressing concerns that our schools face: racial disparities, stagnant scores that are falling behind other countries, defective spending structures, high teacher turnover, and a host of other problems. However, they promote a philosophy of education that is effective at exposing these problems but impotent to solve them. The root issue is that the three elements of a progressive worldview I discuss here—restorative justice, contemporary literary theory, and an antipathy to intellectual diversity—result in an education that questions all systems but fails to offer students a coherent alternative.

Restorative Justice and School Discipline

Restorative justice is a central tenet of contemporary educational philosophy and one of the culprits behind the current state of behavior in many public schools. The theory posits that students act out not because they are ‘disrespectful,’ but rather because they either have not learned how to act appropriately from parents or are expressing a deeper emotional need in a destructive way. As such, discipline has little to no place in schools.

To some extent, the theory bears weight. In Teaching with Poverty in Mind, a significant text on educating at-risk youth, Eric Jensen outlines how early childhood trauma alters neurochemistry and ingrains unhealthy coping mechanisms such as aggression or disregard for authority. In response, most schools resort to suspensions and expulsions. Because poverty rates are higher in communities of color, black and Hispanic students receive a disproportionate amount of discipline at no fault of their own. The diagnosis of the problem is correct; restorative justice, the prescribed medication, is not.

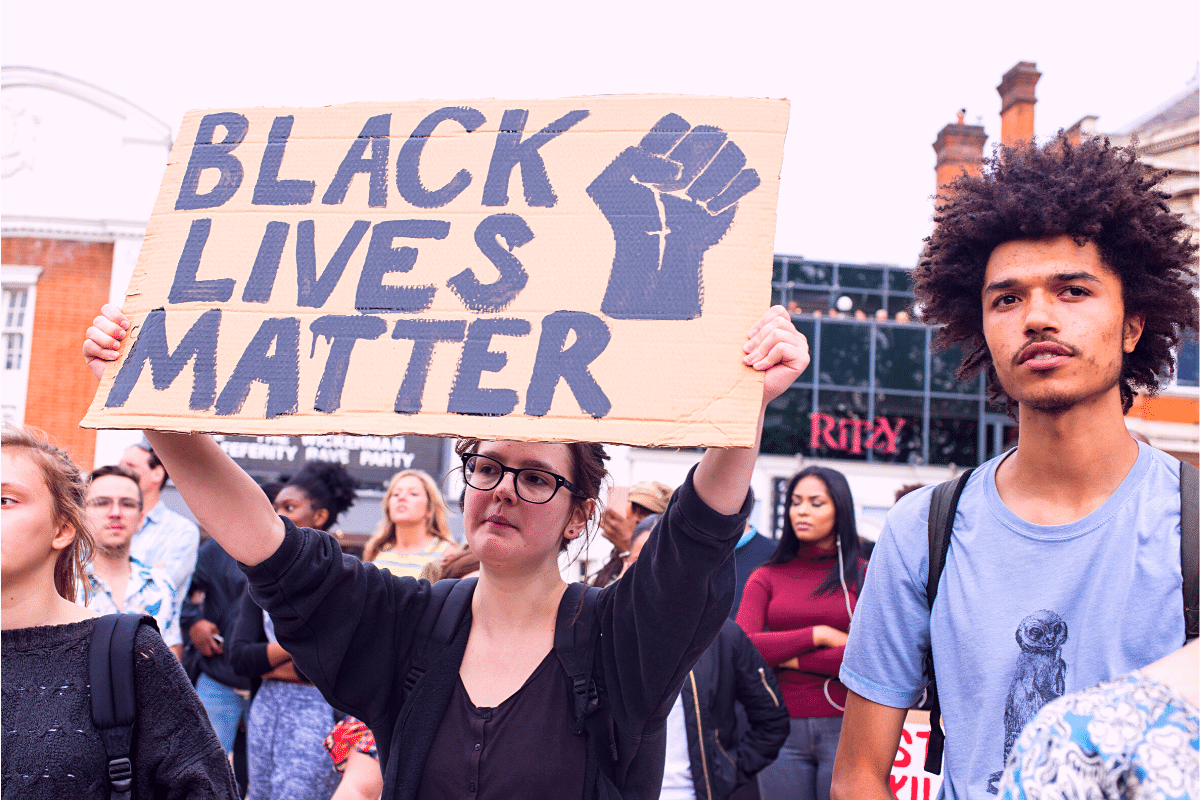

A foundation of this theory is the practice of “restorative circles,” a discussion format with content focused on personal experience. At the university, our instructor posed us with the question: when is one time we had been an oppressor? We proceeded to pass around a “talking piece”—in this case a popsicle stick with googly eyes glued on. Weekly conversations like this always featured a child’s toy as a talking piece and some variety of an oppression-centric question. In the capstone course for my graduate degree, we spent a circle making Black Lives Matter themed friendship bracelets while reflecting on what the movement meant to us.

Paired with restorative circles is the implementation of redesigned consequence structures. Imposed on schools is the necessity for equal rates of suspensions across demographic groups and softer punishments—a discussion with a counselor instead of a suspension. In theory, weakened discipline structures and circles work together to retrain teachers’ brains to see poor behavior as either a mere cultural difference or a cry for help that requires support not punishment; concurrently, students learn how their behavior negatively affects others and so intuitively learn better behavior.

After the RAND Corporation completed a comprehensive review of its effect, media reported restorative justice a striking success; overall suspension rates decreased and the disparity of discipline among racial groups shrunk. Having taught in a school that adopted restorative practices, though, I question what change affected the data. For my school, behavior did not improve; instead, student actions that formerly would have earned a suspension either went unreported by teachers or unaddressed by the administration. Running parallel to my observations is a survey of student perceptions, nestled within the RAND study. According to the students, schools that adopted restorative justice experienced an increase in bullying, an uptick in classroom disruptions, and an overall deteriorating school culture.

Restorative justice isn’t working. It seeks to question what qualifies as a good and bad student; it critiques traditional responses to disruption and misbehavior. In its place, this deconstruction of behavior norms has resulted in few—if any—systems of consequences, leaving administrators unable to call poor behavior what it is and without any tools to fix it. School cultures are suffering for it.

Literary Theory and What We Teach

While literary theory may be an esoteric trifle to most, students read the foundational texts of Western literature in school, making English classrooms the space where teachers most inculcate a worldview and civic values. Thus, the philosophy of how literature should be taught is arguably one of the most important ideas in education. Unfortunately, contemporary theories impart a way of thinking that closes the mind off to the new ideas and ideals literature has to offer.

In a broad scope, there are three approaches to reading. What could be called the “traditional approach,” sees any work of literature as containing a definitive statement by its author, which the reader is asked to uncover. A more popular approach is “reader response theory,” which says that there is no way to uncover any definitive meaning in a text and so all that is important is our subjective experience. The third general theory, the one that is taught at the university, is “critical theory.” It treats any work of literature as a cultural artifact through which we critique the society in which it was written.

In a method’s course, where we were to learn the practical aspects of teaching, we spent a day on literary theory. Scattered across various tables were short explanations of each theory. Moving throughout the room, my classmates and I analyzed the same poem through different “lenses.” We moved from critical race theory to feminist theory, Marxist theory, and deconstructionism—all variations on the overarching “critical theory.” At each table, what the text actually said or taught was secondary to how it exposed oppression or cultural assumptions.

In this mindset, gone are the varied perspectives on love that Shakespeare provides in Romeo and Juliet: Romeo’s idealism, Lady Capulet’s utilitarianism, Mercutio’s flippancy, and the Friar’s doctrine. Instead, Romeo and Juliet become a story of female oppression and class battles. These are important discussions, yes, but with this theory, the same discussion of oppression is then repeated with Hamlet, The Great Gatsby, Don Quixote, or any other work of literature.

At the root of the issue is the lack of an ideal with which literature can present students when analyzed through critical theory. The child psychologist James Marcia studied identity development and determined two things that adolescents need to develop a well-adjusted sense of personhood: exploration and commitment. They need to explore potential vocational paths and moral codes, and then they need to make a definitive choice.

In contrast to critical theory, T.S. Eliot believed that the ideal poet removed himself and his emotions from his work, introducing the reader to ideas themselves. Thus, a book, a poem, a play, or any other work of art is not just a cultural artifact but a statement to be considered. Understood this way, books give students, as Marcia recommends, substantive alternatives to both explore and choose, thereby aiding the achievement of a healthy mental state.

Critical theory, however, closes ears to the voice of the author and instead encourages a deconstruction of preconceived notions—about gender, politics, ethics, religion, etc—without providing the students with an alternative apolitical reading. Once a student has criticized or deconstructed their culture’s norms, they have no tools to seek something better. It leaves them in a state that Marcia calls “identity moratorium,” a listless state of purposelessness and anxiety.

Intellectual Uniformity

The antipathy towards intellectual diversity on campus has been much discussed. It will come as no surprise that I was accused of white supremacy and intentional segregation for allowing a student of color to self-select a seat in the back after they had asked in private to sit there—they had been too close to their friends and unable to focus. Similarly, I am not the only student in a university who has received audible clucks of disgust because I asked if an article contradicted itself. However, a teaching program that practices intellectual uniformity has a unique consequence: the monotony and mediocre homogeneity of public schools will not change in this environment.

There are myriad ways to teach any class; I’ll use English as my example as it is my specialty. The progressive techniques I learned at the University would have me set traditional works like Shakespeare in conversation with contemporary works of art like rap songs or movies, and then compare the biases or stereotypes present in both. A more traditionalist school, military or religious, would explain the meaning of a work explicitly to their students, only to ask them to restate the information on a test. A charter school would teach students four explicit steps for analysis, practice a few times, and then have students repeat the process unaided for a test. Montessori schools let students develop their own curriculum under the guidance of adults.

If there is one certainty within educational research, it is that there is no single distinct and best way to teach. Instead, different methods emphasize different skills and succumb to certain drawbacks. As such, the question is not what is best but what kind of student development do we want to encourage and with what skills.

Ken Robinson, Professor Emeritus at the University of Warwick, popularized a critique of the “factory model” of schools; that students are shuffled along a conveyor belt, responding to bell calls and repeating motions, and end up carbon copies by the time they graduate. Perhaps a progressive model of education would break this specific norm, but in its place, it just creates another carbon copy model.

Speaking more generally, many public schools are failing because they provide the same product to a student living in Brooklyn, to one in small-town Appalachia, and to another in my mid-sized city in Wisconsin. Until a diverse range of ideas is allowed in teacher training programs, there will be a uniformity of teaching methods in the schools.

A Concluding Anecdote

The consequences of progressive theories of education are best shown through an example. Every teacher has certain students who leave a significant impact on them. Mine is the kind who got sent to the office almost 40 times in one semester and had over 15 days of suspensions. He had recently immigrated to the United States, fleeing corruption and violence. He was the kind of student who knocked computers to the ground and cussed out teachers.

One day, he opened up to me. He told me about his insecurities, about his mother’s tendency to ignore him even if he addressed her directly, and about his overwhelming sense of failure and helplessness. Within the progressive theories of education, we could have questioned how he relates to his friends or examined laws that brought this reality to bear. However, if you were to ask me why he should change, I would be left without an answer, without a code of behavior I could recommend to which he could be held accountable, without ideals in literature which he could be invited to consider, and without the freedom to teach him in a distinct manner that might better fit his needs.

There are universities and institutions that are challenging this status quo. Various academics at the University of Arkansas are studying the benefits and drawbacks of various market-based initiatives like school choice, merit-based pay, and pension reform. Systems of charters like Uncommon Schools and KIPP are observing the varied practices of the most effective teachers and disseminating materials to educators across the nations. The scholars at Fordham Institute are questioning both traditional and progressive methods of teaching and public policy to determine the most effective balance between the two.

When my advisor accused me of racism for expressing conservative views, I asked what she would she have me do. She gave no response and ended our final conversation. Contemporary educational philosophies seek to question Western society and various cultural structures but fail to provide any substantive alternative. In response to Plato, educational departments across the country are saying “nothing.”