Politics

Why Australia Opted for AUKUS

While Reuters reports that the French had ample warning the project was in trouble, the AUKUS announcement and the cancellation of the submarine contract nevertheless took them by surprise.

There's more to Australia’s decision to cancel its submarine contract with France than offending the French, risking an EU free trade deal, allowing “floating Chernobyls” into Sydney Harbour, and further antagonising China, its largest trade partner. As well as committing to closer defence technology sharing arrangements with two of its “Five Eyes” intelligence partners, Australia has reversed a decades-old, clearly stated assumption in government papers repudiating nuclear powered submarines.

As recently as 2016, a Defence Science and Technology report on submarines said: “The Australian Government has ruled out the nuclear option since Australia lacks the appropriate infrastructure, regulation guidelines and procedures to successfully build and operate nuclear submarines, and the time required to amass such support systems and skilled people would extend beyond the timeframe for replacement of the Collins class fleet” (which is the 2030s).

The decision not to use nuclear propulsion on policy and logistical grounds caused extensive problems when the Collins class submarines were in the design and build phases in the 1990s and early 2000s. According to the 2016 paper, “problems were encountered with excessive boat noise at higher speeds and an underperforming combat system.” These problems attracted negative media reports for years.

Even so, back in 2016, the Australian government was still ruling out nuclear propulsion for its submarines. Consequently, it signed a contract with the French to deliver 12 diesel-electric submarines to be named the Attack class. They were to be a conventionally powered version of France’s existing nuclear-propelled Barracuda class. And just like it did with the Collins class, the Australian Government opted for a custom build rather than buying “off the shelf.” By 2021, negative stories about cost blowouts and delays for the new Attack class had been running for years. According to Reuters, the French contractor, the Naval Group, had plenty of warning the project was in trouble.

Meanwhile, between 2016 and 2021, the relationship between China and Australia sank to new lows. In November 2020, the Chinese issued a list of 14 grievances that would need to be addressed in order to improve relations between Canberra and Beijing. They were upset about Huawei being denied access to 5G network contracts and other large investments in Australia on what Beijing termed “unfounded” national security concerns. They objected to the Australian government speaking out against Chinese activities in the South China Sea, Xinjiang, and Hong Kong. They objected to Australia’s views on Taiwan and calls for a thorough WHO inquiry into the origins of COVID-19.

Relations between the US and China deteriorated during this time as well. President Trump imposed tariffs complaining of unfair trade by the Chinese. He also berated US allies about not pulling their weight in defence. Several European nations in NATO were consistently spending less than two percent of GDP.

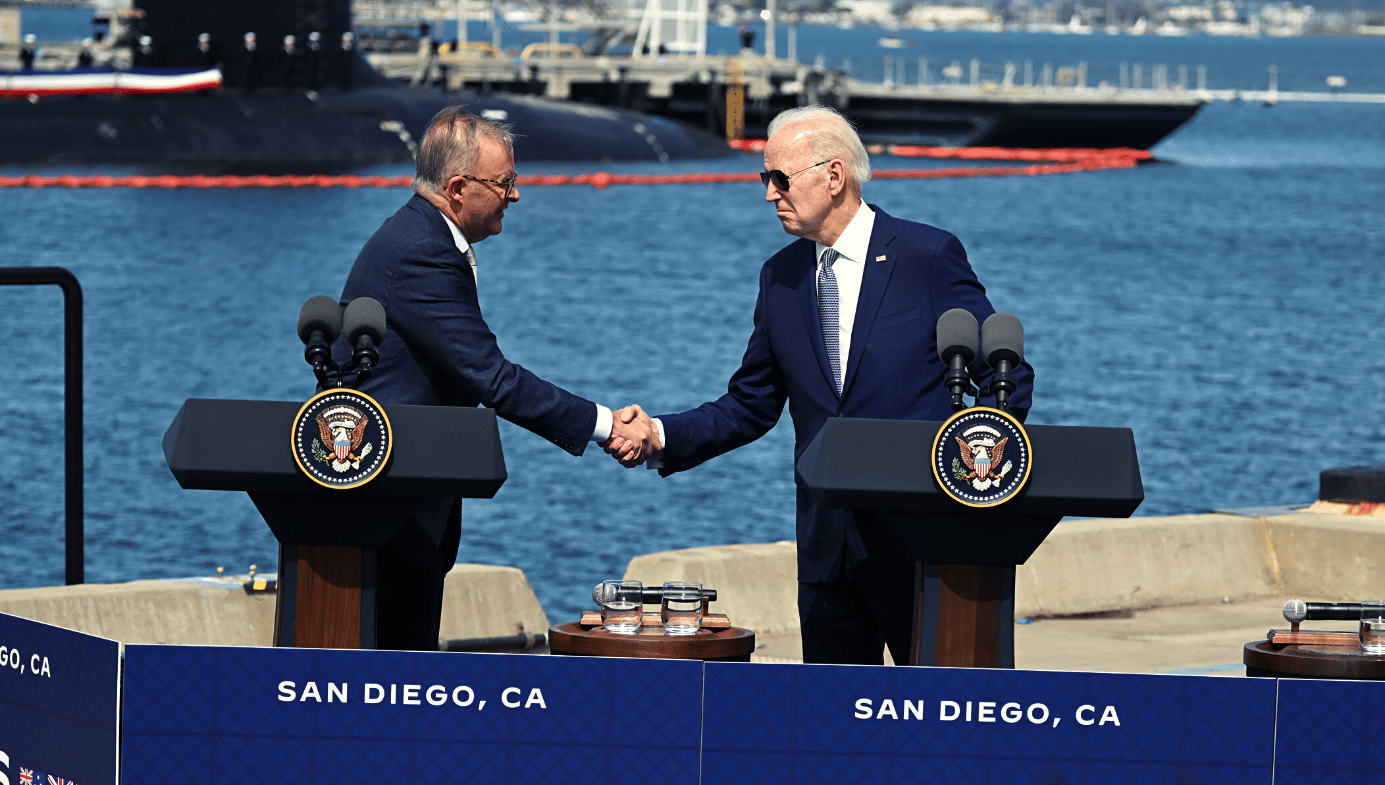

Noting the increase in Chinese naval shipbuilding, Australia’s defence planners and policymakers began rethinking their long-standing reservations about nuclear propulsion. Australia had asked its closest allies for this technology before but the US and the UK had demurred. Exploiting existing close intelligence contacts in the “Five Eyes,” the Australians started to sound out the US and the UK about sharing critical technology as well as critical intelligence. They found considerable support for the idea. Under Joe Biden, the Americans were keen on restoring alliances neglected by Trump. Under Boris Johnson, the British were keen to put some flesh on the post-Brexit idea of “global Britain.” Consequently, Scott Morrison, the Prime Minister of Australia, got a sympathetic hearing. Discussions were kept secret. The three leaders convened in a side meeting at the G7 meeting in Cornwall in July to finalise agreement of the pact at the top level. A few weeks later, on September 15th, AUKUS was made public.

The headline commitment was that AUKUS would “focus immediately on identifying the optimal pathway to deliver at least eight nuclear-powered submarines for Australia.” This provided a credible alternative to the troubled French project and enabled Australia to cancel the contract, which was done only hours before the public announcement of AUKUS.

The French were not impressed. While Reuters reports that the French had ample warning the project was in trouble, the AUKUS announcement and the cancellation of the submarine contract nevertheless took them by surprise. They responded with vigorous complaints, the most colourful of which was that Australia was behaving like an adulterous groom announcing he has a new mistress on the eve of a wedding. The analogy is not entirely inept. It is true that Australia dumped the French for a better strategic offer and the French were kept in the dark about Australia’s Plan B.

Even so, as a result of jilting the French at the altar, Australia now has a choice of two state-of-the-art nuclear submarines that are already in production, the US Virginia class and the UK Astute class. Some say AUKUS is a coup for Australian diplomacy. Others say it was a mishandled blunder.

One of the reasons the French were so angry at the contract being cancelled is that they offered Australia nuclear propulsion in secret talks but the offer was not taken up. The French embarked on five years of design work to alter the design of a nuclear boat to accommodate diesel-electric propulsion. Now they find themselves with a cancelled contract because Australia has changed its mind and decided to buy nuclear powered submarines from the UK and the US when the French were willing to sell Australia nuclear propelled submarines. The amount spent by the Australian government on the abandoned project to date is AUD 2.4 billion.

Historically, the politics of uranium and nuclear power have presented difficulties for Australia’s politicians. While Australia has more reserves of uranium in the ground than any other country, uranium mining and nuclear power have been viewed with suspicion by voters. When news of the first main deliverable of the AUKUS security partnership broke, Adam Bandt, the Green MP for Melbourne, tweeted: “This dangerous nuclear submarines move puts floating Chernobyls in the heart of Australia's cities.” The Greens, he said, would “fight this tooth and nail.”

On the other side of the Tasman, Jacinda Ardern said nuclear-powered submarines would not be welcome in New Zealand. Twisting the diplomatic knife a little more, the French suggested that Australia would no longer be seen as a reliable and trustworthy partner in a complex negotiation such as an EU trade deal. However, domestically, the opposition Labor party has offered conditional bipartisan support. The Leader of the Opposition, Anthony Albanese, has said AUKUS would remain in place under a Labor government. Thus, barring electoral Armageddon for the main parties in Australia, AUKUS is here to stay.

The rationale for nuclear propulsion is simple: it means the submarine does not have to come up to periscope depth to “snort” air to run its diesels so it can charge batteries to run its electrics. While electric motors are extremely quiet, having to come up to periscope depth exposes a submarine to an increased risk of detection. Also, diesel power requires large tanks and a location to refuel. A nuclear-propelled submarine need not snort or refuel. It can stay submerged in a forward area devoid of friendly bases for months. Indeed, with nuclear propulsion, the main limit becomes the endurance of the crew, who still need to eat, drink, and breathe.

The French accused both the US and Australian governments of betrayal and recalled their ambassadors from both countries. French President Emmanuel Macron is reportedly livid. Under the circumstances, given the French offered a nuclear option, that is understandable. However, not everyone is sympathetic with the French for losing a plum contract. After all, they are not above bending EU rules to prefer their own contractors when it comes to defence.

It is likely that Australian ministers meeting their French counterparts experienced a strong sense of déjà vu, with overruns and delays in submarine procurement. Most of them will remember reading negative media about the Collins class. Many commentators have said over the years that a mid-sized power like Australia would be better off buying a well-designed submarine “off the rack” from a reliable ally rather than an expensive “custom” solution with a short production run. It appears Australia’s ministers had no appetite for another submarine project running late and over-budget.

When it comes to submarines, no ally is more reliable for Australia than the US. A VLF (very low frequency) facility the US uses to communicate with its own submarines in the Indian Ocean lies in Western Australia. Also, a critical joint US-Australian signals intelligence facility is located in the Northern Territory. One might add that the US has more commitment to the Indo/Pacific than either the UK or France, given that Hawaii is in the Pacific, and Washington, Oregon, and California are adjacent to it. Further, Australia fought alongside the US in World War I, World War II, Korea, Vietnam, Gulf I, Gulf II, and Afghanistan. Interoperability between Australian, US, and British forces is high. The language is the same. The cultures are similar.

Consequently, it makes a lot of sense for Australia to buy nuclear-propelled attack submarines from allies. Australia is already buying US F-35 fighters and various other items of US military equipment “off the shelf” and has a substantial order for UK frigates. Dropping the long-range conventional propulsion requirement will enable Australia to buy nuclear-propelled submarines “off the shelf” as well. This should reduce risk, save money, increase interoperability, and result in more reliable delivery times.

Now that the objection to nuclear engines in submarines has been withdrawn by the Australian government, it will be critical to work out the “optimal pathway” for Australia to acquire the capability to build and maintain them. A key benefit of AUKUS for Australia is likely to be a solution to the nuclear maintenance question. A likely outcome will be an expansion of the existing submarine facilities in Adelaide to enable them to build and service nuclear-propelled submarines. Politically, this will be controversial but no more so than opening new uranium mines or building the Hell’s Gate dam. Historically, the opposition Labor party has split on uranium. Some unions stress the environmental risks of nuclear projects. Others see highly paid jobs and stress the fact that for many nations nuclear power is an integral part of plans to their commitments under the Paris Agreement to reduce emissions.

There will also be sharp questions about the enrichment of the uranium used to power the submarines and disposing of the nuclear waste they generate. These are sensitive matters but few defence commentators see them as insurmountable. It is by no means a given that nuclear waste would be stored in Australia in any case. Both UK and US submarines come equipped with highly enriched uranium reactors that have enough fuel inside them to run a submarine for 33 years. As for what happens to these reactors at the end of their working life, both the US and the UK have experience in these matters. Besides, the amount of spent fuel is tiny, since the reactor in a submarine only has to power a single vessel not a city.

The main domestic political problems for Australia’s politicians will be how the voters react to nuclear propulsion and the inevitable “no nukes” campaigns that will result. Internationally, there are also likely to be concerns about starting a new arms race.

AUKUS also gives Australia the ability to lease US submarines to cover any capability gap that arises as the Collins class is phased out. While submarines were the substance of the initial announcement, the AUKUS “enhanced trilateral security partnership” also covers cooperation in defence projects involving artificial intelligence, quantum computing, and cyber capabilities.

As yet, there is no precise commitment as to what Australia will buy from the US and the UK. There is an 18-month period for this to be sorted out. A key detail will be how Australia meets its obligations under the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons. Commentary on compliance with the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons was conspicuous by its absence, as none of the AUKUS powers have signed it. Even so, in the initial AUKUS press conference all three leaders were at pains to stress that the new Australian submarines would not be nuclear-armed. However, it is likely that there will be projects to augment the manned submarines with unmanned underwater vehicles (UUVs), as such projects are already underway in the US and the UK.

In a recent strategy document on intelligent autonomous systems (IAS), the US Navy commented on the strategic implications of a war fought with IAS. They noted how the Azeri use of small, cheap drones enabled a swift victory in its 2020 war against Armenia. Much as drones have taken over the air, naval planners expect drones to play an increasingly large part in war at sea.

The IAS strategy document goes on to spell out how it will promote the increased use of AI and robotics in the military and reduce procurement times. Given this, one might question the emphasis on manned submarines. As the future unfolds, there is likely to be an increased emphasis on long-range, intelligent, stealthy (and cheaper) autonomous submarine systems. Telepiloted Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) have displaced manned aircraft for intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) missions because UAVs can be smaller, cheaper, more expendable, and remain airborne much longer than manned aircraft. AI does not need to eat, drink, or breathe, it just needs a power source to fight. Increasingly, AI can outperform humans in combat.

For the same reasons, UUVs will replace or augment manned submarine craft for ISR and strike missions at sea. The current Australian “loyal wingman” project is designed to augment crewed aircraft. Similar projects will augment and possibly replace crewed submarines. While there is no obstacle to telepiloting in the air (apart from enemy counter-measures such as jamming and electromagnetic pulses), deep water is a significant obstacle. Consequently, autonomy in military UUVs is likely as Very Low Frequency and Extremely Low Frequency transmission cannot support telepiloting at depth due to acute bandwidth constraints. While there is a strong military case for systems that remove humans from the front line of warfare (as recently demonstrated by the Azeris), such systems are frequently attacked as “killer robots” by opponents of AI.

Eminent figures in the field seem to be wedded to an increasingly dated assumption that superhuman performance in Chess, Go, and the analysis of protein folds can be achieved by AI, but that superhuman performance in normative domains (such as compliance with military law) cannot. Given the current pace of innovation in AI, it seems to me that superhuman performance in ethics and law is inevitable.

This is not to suggest it is imminent or easy. Nor do I know how long it will take. What I do know is that we live in turbulent times, buffeted by waves of accelerating technological disruption and endemic information warfare. Australia’s submarine force and the ever-expanding role of AI within the military will prove controversial for years to come.