Politics

Why AUKUS Matters

The deal is a belated response to the Chinese Communist Party’s mushrooming belligerence.

When a team of Victoria police officers made the decision to fly a Chinese flag over their station at Box Hill one autumn day in 2019, they managed to inadvertently capture the strange moment Australia was living through. They had hoped to “honour … the local police station’s strong relationship with the local Chinese community.” They honoured no one but the Communist Party, which was busy extending its tentacles into all areas of Australian life. The date? The 70th anniversary of the Party’s assumption of power in China. The flag? A symbol of the Party, not of China, and the mark of a long, covert, multifaceted war waged against liberal democracies like Australia’s. That red square stirring in the Box Hill breeze represented Beijing’s imperialist advance, but it also became the occasion for widespread outrage. Australians were waking up to the secret war at last.

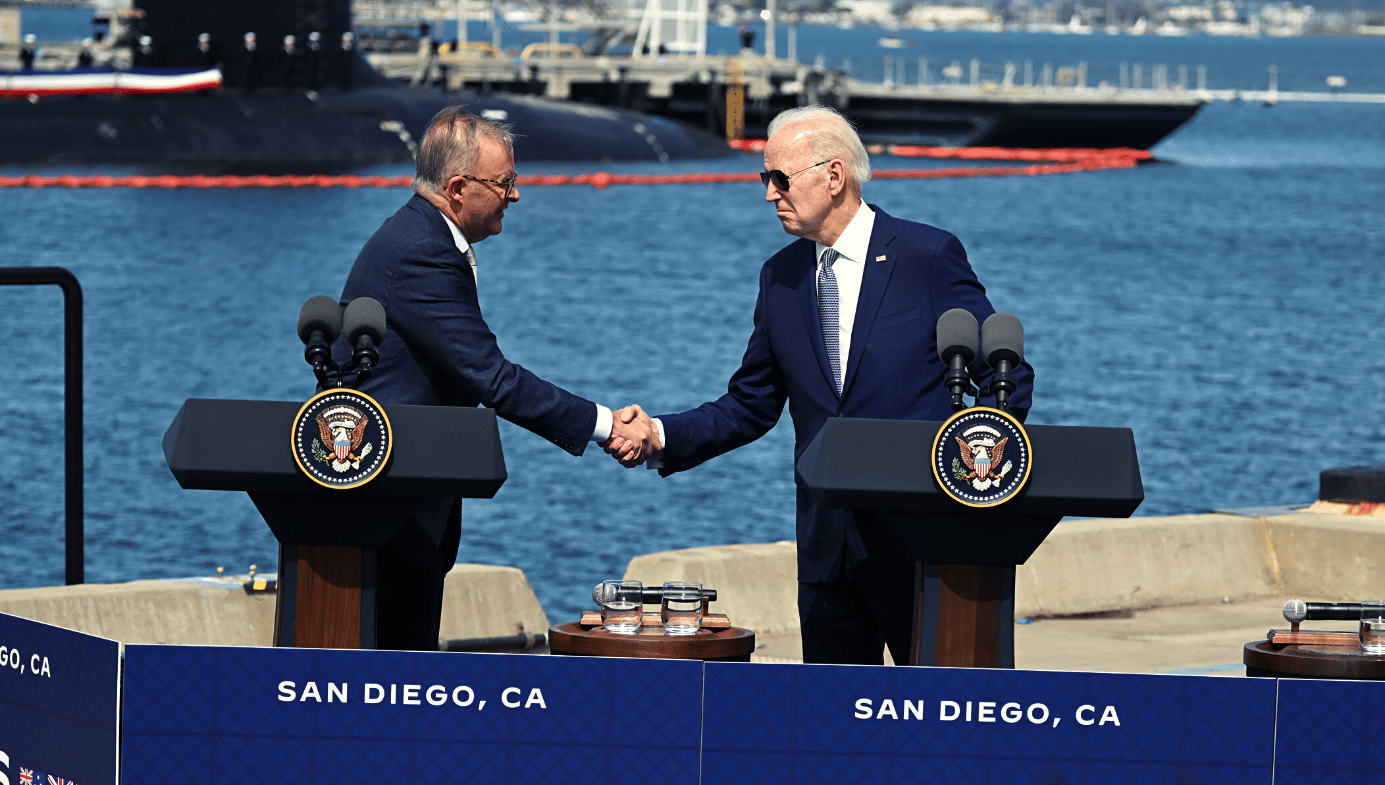

In recent days, Beijing has responded angrily to the finalising of AUKUS, the US-UK-Australia pact arming Australia with eight nuclear-powered submarines. To my eyes, parts of the $AU368 billion deal actually seem like too little, too late. The US is set to provide Australia with three additional Virginia class submarines, but only pending approval from Congress, and only in the 2030s. If war is indeed coming, it could arrive much sooner than that. The UK and US also plan to station their own submarines at HMAS Stirling base near Perth, but not until 2027 (at the earliest). And the Australian navy will receive its first SSN-AUKUS submarine in the agonisingly distant 2040s. That’s time enough for the geopolitical situation to go through many dramatic changes.

Thankfully, the renewed collaboration itself isn’t going to wait two decades. From this year forward, Australian military and civilian personnel will embed with the British and American navies. Australia has purchased long-range Tomahawk strike missiles from the US to integrate into its existing collins-class submarines. And the three states will work together on artificial intelligence, hypersonic weaponry, quantum technologies, and information sharing. Perhaps this is the real reason for the Party’s rancour.

And so we have been treated to the sight of Chinese officials and academics tearing their metaphorical garments and beating their figurative breasts: the deal is “a time bomb for peace and stability in the region”; it leads Australia down “the path of error and danger.” Other comments were calculated to divide. “Australia should not fall into the category of a saboteur of regional security just because of US pressure,” said Chen Hong, president of the Chinese Association of Australian Studies. AUKUS demonstrates that Australia has become a “de facto offshoot of the US nuclear submarine fleet,” said Song Zhongping, a former instructor with the People’s Liberation Army (PLA). This represents “a disservice to Australia’s sovereignty and independence.”

These men spoke partly for the benefit of their domestic audience, painting for the public a cowed Canberra that trembles before Washington’s tyrannous demands. At the same time, their comments were aimed at those in Australia who view the US with distaste. Beijing is particularly keen to drive a wedge between the United States and its allies. AUKUS is a (belated) response to the Communist Party’s mushrooming belligerence, but Beijing will hope that some Australians are still receptive to the evergreen notion of a meddlesome, imperial America. And after the melodrama and the subterfuge, of course, came the threats. Canberra has “officially put itself on Beijing’s defence radar”; nuclear-powered submarines “cannot protect the security of Australia.”

Australia’s location—the nearest of the Western powers—has long made it the subject of CCP interest, and a target for interference. There have been several attempts to subvert the Pacific giant by placing Party associates in positions of political influence. Australian citizens of Chinese heritage have also been recruited for this purpose. Dubbed the huaren, they are considered amenable, tied by blood to Chinese soil, and therefore to its current masters, the Party. In 2019, a Chinese intelligence operative is reported to have offered Australian citizen Nick Zhao between $AU677,000 and $AU1 million in order to finance his election campaign for the Division of Chisholm, in Victoria. Zhao’s response is not known. He was shortly found dead in a hotel room from an overdose.

The CCP also wormed its way into the affections of gullible non-Chinese, funding travel and legal bills for senators such as Sam Dastyari. Dastyari was forced to step down from two separate positions: firstly after accepting money in exchange for supporting China in its South China Sea territorial disputes, and secondly when it emerged that he had given counter-intelligence advice to Party man Huang Xiangmo (by privately advising him that his phone was likely tapped by US authorities).

Beijing even began attempting to silence its Australian critics. The tactics were employed more mildly than back home, but they were recognisable. In Melbourne, journalist John Garnaut (one of the key figures involved in waking up the Australian political establishment) was stalked and intimidated by the Party’s people. He had been writing about CCP interference in Australian affairs. Four Chinese individuals followed him to a restaurant, where they sat at nearby tables, staring him down. Garnaut asked one woman a question in Mandarin and she immediately left. In a scene that typifies for me the dumbfounding amateurishness of the Communist Party, she returned a few minutes later, wearing a differently coloured shirt. Garnaut arranged to meet with the Organised Crime Unit at a café to report the incident, and upon arrival, it turned out that more Chinese were openly filming both Garnaut and the officers from the next table, apparently oblivious to this self-incrimination.

Australia has found itself in a difficult position. By the end of 2020, “more than one-third of every Australian export dollar was earned from the Chinese market.” “Our whole standard of living is virtually tied to our exports to China,” says billionaire businessman Kerry Stokes. The education sector is especially compromised. Three Sydney universities in particular—the University of Sydney, the University of New South Wales, and the University of Technology at Sydney—enrol more mainland Chinese students than any American university.

When Australia’s government called for an inquiry into the origins of the COVID-19 pandemic, it was given a taste of the schizophrenic punishment that the Party can dole out. It was also reminded of the dangers of being so heavily reliant on rich Chinese students. An apoplectic Beijing cut imports of beef, barley, wine, coal, and lobster, demanded that Canberra immediately change its laws on countering CCP influence, ordered the Australian press to censor all criticism of the Party, employed a historically illiterate analogy by comparing Australia’s actions to Brutus stabbing Caesar, had a CCP official tweet a doctored photo of an Australian soldier slitting the throat of a child, and finally toyed with a genuinely serious threat: suggesting to China’s prospective students that they might want to reconsider applying for Australian universities. If the Party ever turned off these lucrative taps, stifling that vast flow of tuition and accommodation fees, then Australia’s economy would certainly feel the pain.

Despite such threats, pushback against the Party’s malign behaviour began in the late 2010s. The Australian authorities banned Huawei in 2018, having recognised the unique threat the corporation poses to any non-Chinese nation’s security and sovereignty, and they persuaded the US and UK to follow suit. Erstwhile Prime Minister Scott Morrison introduced a national security test for foreign investments, and also greatly increased defence spending with a focus on the Indo-Pacific region. Sydney’s University of Technology reviewed its partnership with CETC, a Chinese military tech company that had created an app to track Uyghurs. New South Wales scrapped all of its Confucius Institutes. (Posing as education programmes to teach Mandarin in universities, these are essentially spy hubs.)

Attitudes hardened fast, with Defence Minister Peter Dutton suggesting in 2021 that a war over Taiwan could no longer be discounted, and that Australia was “already under attack” in the cyber domain. Ground and satellite intelligence on Chinese activities is now being shared with Indo-Pacific neighbours such as Vietnam. Gone are the days when Prime Minister Kevin Rudd could assure citizens that Beijing was willing “to make a strong contribution to strengthening the regional security environment and the global rules-based order.”

The Party was caught off-guard by this change in attitude. Since 2018, it has refused to accept cabinet-level meetings with Australian counterparts; since 2020, it has refused to accept phone calls. Furious state editorials deride Australia: “ungrateful,” an “upstart.” Now AUKUS may have damaged the relationship irreparably.

But in the context of the Communist Party’s naked ambition, Australia’s ability to defend itself has never been so important. The stakes are enormous. PLA training manuals talk of “surpass[ing] the West’s thinking” and forging “an innovative way forward for global governance.” These textbooks are refreshingly blunt: “mankind needs a new order that surpasses and supplants the [Westphalian] balance of power.” When visiting Beijing a few years ago, sinologist Kerry Brown (a man with access to the corridors of power) was told quite simply that Xi wants to rule the world.

That will probably never happen, but great danger lies in the attempt. The Party slithers into multiple UN agencies, intent on undermining the liberal world order. It has already seen success: the United Nations now grants serious consideration to Party proposals, such as state control of the flow of information to every network-connected device. As Benedict Rogers has explained in his book The China Nexus, Chinese nationals now head UN agencies such as the Department of Economic and Social Affairs, which receives $20 million a year from Beijing for the explicit purpose of advancing the Belt and Road Initiative within the UN system. The only people who get to decide how those funds are spent are the secretary-general, his chief of staff, the Chinese permanent representative to the UN, China’s Ministry of Commerce and Foreign Ministry, and the auditors.

Until recently, Chinese nationals also headed the International Civil Aviation Organisation, the Industrial Development Organisation, and the International Telecommunication Union. The last of these was successfully persuaded to promote policies enabling governments to use technology for the repression of citizens. Farcically, China has been accepted onto the UN Human Rights Council despite the humiliating fact that the Communist Party does not allow this body to investigate human rights concerns in China.

Beijing inveigles the phrases “win-win co-operation” and “mutual respect” into UN documents, hoping to legitimise the idea of nations maintaining their own completely independent (i.e., non-liberal) political systems, while not interfering in the business of neighbouring (presumably non-liberal) states. Of course, the truth is that the CCP routinely interferes in everyone else’s business—the real intention of this phraseology was always to swat away critics of Beijing while it climbs the long pole to hegemony. In China-watcher Ian Easton’s succinct summary, “The CCP’s mission is to gain access to the international system without being changed by it, to gain enough leverage to subvert it, and then to remake that system in the model of its own totalitarian form of government.” Already, most member states can be relied on to support China, because they depend on the Middle Kingdom for loans, infrastructure, and cheap tech. They refrain from critiquing Beijing’s horrendous human rights record, and they agree to shun Taiwan.

Meanwhile, the Party continues to ratchet up its military capabilities, from deep ocean to outer space. It hopes to seize the reins of the much-mooted Fourth Industrial Revolution and leave other nations in the dust, just like Britain did in the 1700s. The chaos of the past few years has left the CCP in a weakened position, but that hardly means the danger has passed. As Michael Beckley has convincingly argued, when an aggressive expansionist power realises that its window of opportunity is closing, it presents a particular potential for menace.

The peril is greatest in China’s periphery, which includes Australia. Xi has already created and militarised seven artificial islands in the South China Sea. Japan, Brunei, Vietnam, Malaysia, and the Philippines are all claimants to other disputed territory in the surrounding area, and as such, they find themselves routinely harassed by Beijing’s navy. The region’s sea lanes pulse with Chinese traffic: warships, armed coastguard, and fishing vessels (the maritime militia).

Taiwan, of course, is the primary flashpoint. All that drama—AUKUS, Australian security fears, quarrels in the South China Sea, Japanese re-militarisation—all of it is playing out in the huge and unavoidable shadow of the Taiwanese question. If the PLA invades Taiwan, then the global balance shifts decisively and historically, and no one is safe. The island’s future matters to the whole world.

Such an invasion would breach the “first island chain” of Pacific archipelagos flanking China’s east coast, purposed as a method of anti-communist containment since the days of the Korean War. (Australia itself lies just beyond the “second island chain.”) The CCP would win for itself what has been called an “unsinkable aircraft carrier” from which it could project power across the western Pacific. It would gain the ability to choke off oil shipments to Japan and South Korea. Most states would immediately fall in line with Beijing’s various demands, fearful for their own safety.

Pax Americana would collapse. Chaos would reign. Further territorial expansion would be inevitable. The Party may want to take control of the region’s US territories and possessions: American Samoa, Guam, Hawaii, the Northern Mariana Islands. More certain would be the return of old-school imperialism. The CCP’s notion of “Chinese” land has always been rooted in the distant past: Tibet, Xinjiang, and Taiwan all “belong” to China simply because they were controlled by Chinese emperors at various stages of the nation’s history. This logic could easily extend to Vietnam and Korea.

Japan would certainly not be safe, considering Beijing’s obsession with the two nations’ historical enmity. The terrible crimes of the Imperial Japanese Army in Nanking circa 1937–8 are drilled into the minds of every Chinese mainlander at school, along with the hatred they are expected to feel towards every single blameless descendant. And most of them feel it intensely. Chinese taxi drivers casually inform passengers that they long for the day when the CCP will kill every Japanese man, woman, and child. It was the Party itself that lovingly cultivated this mania. So what will the Party do once it possesses the means and the strategic advantage to punish Japan?

A successful invasion would result in the CCP taking control of some of the most cutting-edge technologies in existence—notably the world-beating semiconductors at TSMC (described by historian Niall Ferguson as “the microchip Mecca”). With 80 percent of global semiconductor production now under its control, Beijing could wage potent economic warfare on Western countries. Inevitably, many heads of state would end up deciding that perhaps those human rights concerns they kept talking about in the past don’t matter quite so much after all. “He who rules Taiwan,” Ferguson has observed, “rules the world.”

A messier invasion would not produce a happier result. In the chaos of war, the PLA may struggle to seamlessly assume control of Xi’s coveted microchips. “Were production at TSMC to stop,” reports the Economist, “so would the global electronics industry, at incalculable cost.” The US has a long way to go before it can catch up with TSMC’s level of sophistication—China longer still. And disruption would affect more than just semiconductors: a Taiwan War could transform the world’s most important shipping lane into Armageddon. Estimates suggest a war would reduce Chinese exports to America by $100 billion. Millions of people would plunge through the trapdoor into poverty. A worldwide depression is certain.

Taiwan has a population of 24 million people crammed into dense urban areas (9,575 people per square kilometre in the capital city of Taipei), which creates the potential for civilian carnage many times worse than anything we’ve seen in Ukraine over the past year. And if the Communist Party wins full control, then the nightmare would really begin. “After re-unification,” said the Chinese ambassador to France last year, “we will do re-education.” Uyghurs and Tibetans know the visceral hell that lurks behind that bland euphemism. Any ethnic subcategories that prove to be “deviant” will experience the uplifting of their “bio-quality”—a notion all the more terrifying for its vagueness.

Taïwan: "Après la réunification, on va faire une rééducation", affirme l’ambassadeur de Chine en France pic.twitter.com/as6hM5U9lS

— BFMTV (@BFMTV) August 3, 2022

Even a fast and decisive victory for the US, Japan, and Taiwan would involve the loss of dozens of ships, hundreds of aircraft, and thousands of lives. America’s global position would be severely damaged. Taiwan would be left ravaged and gutted: a ruined economy without electricity or basic services.

There are various possible outcomes to a Chinese invasion of Taiwan. Each one is disastrous. At all costs, we must deter Beijing. From Australia to Japan, everyone in the region should be scaling up militarily. This is no time for nervous quibbling about the risk of “provoking” a war via attempts at deterrence: the Korean War provides us with an instructive example of the dangers that follow a failure to act and fear of confrontation. Sī vīs pācem, parā bellum, as the Romans used to say: if you want peace, prepare for war. We need to make a Taiwan War unwinnable for the PLA, and most importantly, we need to convince them that this is the case. AUKUS represents a step in the right direction, but much more is needed, and much faster.