Activism

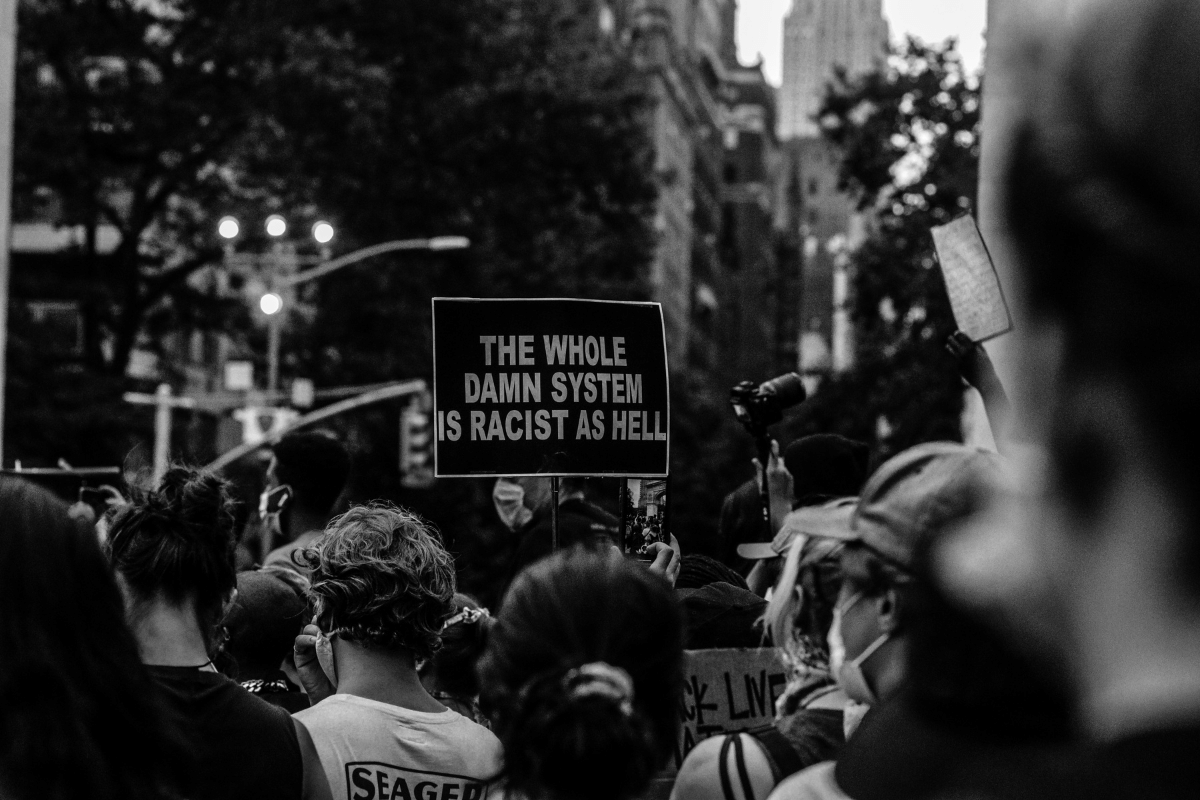

The Faith of Systemic Racism

The radicals, always livid, always demanding more, insist that all this is window dressing. A sham.

We hear constantly about the systemic racism coursing through America. Everything, we’re told, is shot through with hate. It does not matter if no white person ever has actually thought a hateful thought. The structure, or system, these innocents inhabit and profit from was designed by those who hated with abandon; the hate is baked into the edifice and walls and rooftops. It constitutes an architecture of oppression, and the persistence of that architecture amounts to an indictment of its beneficiaries. They’re fools or, more likely, willing participants who go to inordinate lengths to camouflage their complicity—Dean Armitage of Get Out declaring he would have voted for Barack Obama a third time while living on a latter-day plantation.

Of course, if a system is nefarious, it must be blown up, and the bricks and rubble must be redistributed to the politically favored, and anyone who opposes that—anyone who does not loudly and enthusiastically embrace the new dogma—must be a tool of white subjugation.

This is the not so hermetic logic of most every blue-chip multinational, tech behemoth, university, studio, streaming service, and media conglomerate, which, in the past year, have committed to even bolder and brasher equity targets meant to inoculate those institutions against charges of systemic racism.

The radicals, always livid, always demanding more, insist that all this is window dressing. A sham. It does not matter how much money retailers spend on black-owned suppliers, or what percentage of Princeton’s class of 2025 is BIPOC, or how many movies we watch starring a correctly hued Afro-Dominican. The radical does not negotiate with an eye toward arriving at some peaceful coexistence, but a weakening—a razing—of the old order.

There’s something mystifying about all this endless, unctuous yammering about “systemic racism,” and that is its unverifiability. When the radicals call something “systemic” or “structural,” what they really mean is invisible or, better yet, incapable of being experienced. They are referring to the racism that must exist by dint of our many inequities. They assume a causation they cannot assume. Yes, there is disparity between racial groups. No, we cannot declare that the opinions of dead white people caused that disparity. David Hume was skeptical of asserting that contiguity in time and space was the same thing as causality. In this case, we can’t even go so far as to assert a contiguity in time. We can simply assert a vague contiguity in space. We can say that in America—like many, if not most, places—people once believed reprehensible things. We certainly can’t experience systemic racism, not in the way that “experience” is understood by philosophers or, for that matter, judges. We can’t see or hear or taste or feel it, the way an electric current coursing through a live wire can be felt. Which means we can’t be sure it exists. All we can do is assert, with great conviction, its existence and insist that other people believe in it, too, and threaten them with censure or exile if they believe inadequately.

Alas, if one points this out, if one so much as suggests that we consider other explanations for racial disparity, one inevitably risks being charged with racism. Serious inquiry is verboten.

All of which is to say we are dispensing with the empirical, and conflating truth and belief, and migrating from the logical to the religious, from the rational to the arational. In the context of organized religion, we’re unbothered by arationality. We expect it. We bracket it. We say, This is separate from everything else. This is how we reconcile our technocratic and spiritual identities, the modern self and the self that stretches back to our mythical-primal state.

Until recently, this bracketing enabled us to be simultaneously logical and illogical. Logical in our everyday lives. Illogical while exercising our faith.

Alas, most major institutions in America right now are making important decisions about hiring, firing, investment, programming, content, syllabi, and so forth, on the basis of a religious claim—systemic racism permeates the whole of our existence—that is necessarily unverifiable. They are being illogical when we expect them to be logical.

The people who run these institutions, one imagines, would respond that they’re doing what the market demands of them. Their decisions, far from being illogical, are calculated and strategic. You idiot, they’d spout, we’re responding to shifting expectations. We’re acknowledging that the way we used to do things does not comport with the way we think now.

The problem is the way we think now. We are not so good at bracketing anymore. Our two selves, our modern self and our mythical-primal self, intertwine and bleed together. We like to believe that the modern self will soon obliterate the mythical-primal self, that an ever expanding reason will inevitably banish from the human experience any vestige of the old drug. That we will finally molt our ancient, religious longings.

How funny, the conceit of the modern.

It turns out that those longings—while arational, while residing outside the realm of reason—are not irrational. They do not run counter to reason. There is a basis for our religion. Religion exists because humans possess the cognitive furniture to think philosophically. We are not content with simply existing. We want to know why we exist, and we want to know why we have the cognitive furniture to ask the question in the first place. We find it unimaginable to contemplate the possibility that there is no reason, that the whole of humanity is an unplanned pregnancy. It’s true that organized religion has lost much of its numinous glow, but the underlying spiritual impulse, or longing, is the same as ever. It cannot be snuffed out.

So, we try to reconcile our belief that the modern will eclipse the mythical-primal with our belief that we exist for a reason. That we have meaning. Today, that reconciled belief is reflected, with greater frequency, in a stripped down spirituality, a spirituality devoid of religion. In our meditation, veganism, environmentalism, identitarianism, wokeism—whatever we require to feel anchored to something bigger than us. We want to believe that we are not just bookended by eternities, that our existence rises above the darkness that makes a mockery of the very idea of human meaning.

Enter the radicals, who pride themselves on their atheism. When the radicals declare that there is a mysterious, omnipotent force controlling the whole of America, we are more susceptible to their fire and brimstone than we should be. We believe. Or, at least, many of us do. In the not-so-distant past, we would have relegated religious belief to the realm of the formally religious. We would have intuited that one makes leaps of faith in a church or temple or wherever one does those things. One does not make leaps of faith in, say, a boardroom. Today, we do.

It is—let’s not kid ourselves—a tad embarrassing. The whole world, including many Western countries that have reined in or remained mostly impervious to their more intemperate elements, is watching America and wondering what is happening to us. Most Americans, one hopes, one suspects, are still sober. Most (but not all) of these people are those who retain their religion or some semblance of it, those who grasp that there is value in a confined arationality coexisting with the rationality of modern life, who have not lost sight of the distinction between the religious and the merely spiritual. The religious, or religious-adjacent, know that, in its most distilled form, faith elevates and deepens and forces that great existential confrontation of the self that is a precondition for growth. It propels us. It should, although it often does not, make us better.

But then there is the Plurality of the Unwell. Those who are the loudest and most desperate and dangerous. Those behind the new discourse. Those who corner or lobby the people who make the decisions—the CEOs, university presidents, studio chiefs and so on—to pretend that there is a ghost in the machine. That we are being orchestrated by an unverifiable hate. That it is their role, their mandate, to overthrow the veil of false consciousness and lead us to the light. These people, one suspects, are true believers. Their faith is real, but they do not realize it is faith. They would deny vehemently that it is anything of the kind. They believe that they simply know what the old, the dumb, the wicked cannot know. That we cannot make any meaningful distinction between Jim Crow America and America right now. That all of the so-called progress of the past half-century is a distraction and a farce. That we are trapped inside a vast web of manipulations that must be decimated, loudly and with an unbelievable fervor.