BLM

The Strange Rehabilitation of the Black Panther Party

Isn’t it a little late for the rehabilitation of the Black Panther Party (BPP)? After all, the organization that first caught the public’s attention in 1969 was already in its death throes by the early 1970s, beset by internal splits, criminal prosecutions, and violent faction-fighting. Yet, five decades later, the BPP is being energetically romanticized, its legacy is being whitewashed, and its leaders are being valorized in murals, documentaries, and major Hollywood productions that portray the movement and its leaders as revolutionary icons of righteous struggle. The most recent attempt to rehabilitate the BPP began in 2015, when Stanley Nelson’s hagiographic documentary The Black Panthers: Vanguard of the Revolution received theatrical distribution, followed by a nationwide PBS broadcast the following year. Notwithstanding a devastating critique by Michael Moynihan in the Daily Beast, the film received a generally favorable critical reception from a credulous media class and was duly followed by further revisionist histories.

The most recent and popular of these is Shaka King’s 2021 feature film, Judas and the Black Messiah. Daniel Kaluuya plays Fred Hampton—known to Panther members as “Chairman Fred”—who was leader of the Chicago branch of the BPP until his assassination aged 21 in December 1969. Distributed by Warner Brothers, the film was made available in theaters (hardly frequented during the pandemic) and also on HBO Max cable. In the New York Times, critic Lawrence Ware praised the film for revealing that the BPP “were important to my community when I was growing up.” For too long, he declared, Hollywood ignored “the Black Power movement” to focus on whites who opposed racism, offering “lessons” for the benefit of white audiences “on how to better perform their whiteness while in proximity to Blackness.” King’s film, however, is not about whites and refuses to “apologize for Hampton’s embrace of Blackness or his deep suspicion of capitalism”—qualities which, Ware enthused, make it “shocking and exhilarating.”

The Judas of the title was an FBI informer named Bill O’Neal, who infiltrated the BPP and helped the Bureau break the Panthers. Such characters have often been portrayed as sympathetic and courageous figures, such as the Federal mole in Gordon Douglas’s 1951 film, I Was a Communist for the FBI. But here O’Neal is cast as a villain and a coward. Hampton, on the other hand, is portrayed as an idealist who simply wanted a good life for the people of his Chicago community. And so, we see him organizing for civil rights, establishing a free food program and free schools for young children, and generally behaving in a noble and admirable way. The story ends when the FBI, in collaboration with the racist Chicago police department and the Cook County State’s Attorney’s office, murder Hampton during a predawn raid on his apartment. An inquest later found that law enforcement had fired 90 shots, while the apartment’s occupants had fired just one—an accidental discharge into the ceiling. Witnesses reported that, upon discovering that Hampton was still alive, he was executed by an officer who shot him twice in the head. Hampton’s wife and young baby were in the apartment at the time.

Like Nelson’s documentary, King’s movie was acclaimed by critics at many legacy publications eager to advertise their anti-racist bonafides following the Floyd protests and riots of the previous summer. Writing in the Atlantic, David Sims congratulated the filmmakers for not turning the Panthers into “militant cartoon characters,” and for their depiction of Hampton “as a robust screen presence who delivered rousing speeches with aplomb.” That he does, but when I watch Hampton bellow “You can kill the revolutionary, but you can’t kill the revolution!” at a mesmerized audience, he sounds to me like a fanatical demagogue. In a separate article, Sims’s Atlantic colleague Elizabeth Hinton allows that the Panthers “did exercise their Second Amendment rights to carry guns and, as King shows, engaged in shoot-outs with police in self-defense.” But the idea that the BPP was of “an organization that wantonly killed police officers and spewed hatred against white people in an effort to foment the Black revolution,” she suggests, is a calumny against which King rightly “pushes back.”

After a lengthy gun battle with police that destroys the BPP’s Chicago HQ, Hampton and scores of altruistic volunteers rebuild it into a state-of-the-art modern facility. Scenes like these, Hinton approvingly notes, “serve to undermine the FBI’s prevailing narrative about the Panthers.” They certainly do, but was the FBI’s narrative completely wrong? Were the Panthers simply misunderstood Boy Scouts working to provide the underprivileged with free food and childcare, while educating them in the benign tenets of groovy communitarianism? The problem is that Sims and Hinton evidently know extraordinarily little about the Black Panthers which makes them unreliable guides. If they had looked further into their history, they would have found a quite different group to the one whose glamorization they are in such a hurry to applaud. It is a dismal reflection of the post-Floyd era that an ostensibly serious publication like the Atlantic has elected to print fawning revisionism instead.

2021 also saw the publication of The Black Panther Party: A Graphic Novel History, written by David F. Walker and illustrated by Marcus Kwame Anderson. The authors’ bias is made clear on the dedication page, which reads:

TO THE RANK AND FILE OF THE BLACK PANTHER PARTY: THE BROTHERS AND SISTERS WHO COOKED MEALS FOR THE FREE BREAKFAST FOR CHILDREN PROGRAM, DELIVERED NEWSPAPERS, AND WHO LIVED AND DIED FOR THE PEOPLE. YOU WERE THE HEART AND SOUL OF THE PARTY, AND THIS BOOK IS FOR YOU.

Of course, this is rather disingenuous. The book is meant for today’s BLM activists, who are encouraged to honor and emulate the message of the Party, and to draw inspiration from their actions. The dedication is preceded by a quote from Chairman Fred, who enjoins his followers to “FIGHT RACISM WITH SOLIDARITY,” rather than the racism and violent action for which the Party was better known. In a review for the New York Times, Ed Park misinforms his readers that, although the Party disbanded in 1982, “they have lived on in popular imagination because of their militant stance toward injustice”:

Its Ten Point Program (reproduced in full in these pages) was a forceful manifesto demanding “land, bread, housing, education, clothing, justice and peace” for the Black community. In the immediate wake of the horrific killings of Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery and George Floyd, Walker notes that “every single concern” the Panthers addressed—from police brutality to reparations—“is still relevant.”

“A mixture of bravery and dread,” Park adds, “hangs over much of the book. For all the party’s talk of guns, they are only shown being discharged toward the end” by the federal agents who murdered Fred Hampton—an observation that says nothing about the Panthers’ relationship with violence but rather a lot about the selectivity of Walker and Anderson’s historical account.

By 1970, the authors concede, the political situation had changed, and after his release from prison, co-founder Huey Newton’s behavior “became erratic and paranoid, fueled by a deadly combination of substance abuse and unrelenting [FBI] Cointelpro actions against the Panthers.” The group split into warring factions which resulted in internecine violence and murder. In one camp, Newton advocated a future revolution led by the working class. In the other, Eldridge Cleaver, who was hiding from the law in Algeria, favored an immediate revolution led by the underclass—the lumpenproletariat in Marxist terms—including unemployed criminals. As the organization splintered, Newton’s alcoholism and cocaine addiction worsened, and he was eventually shot to death in a crack house by a drug dealer he had been trying to shake down. Meanwhile, in Algeria, Cleaver murdered a Panther whom he accused of sleeping with his wife Kathleen.

The authors also manage to report one particularly nasty incident that many other revisionist accounts either ignore or misrepresent—the torture and murder of a young BPP recruit by the Panthers in Connecticut. As Walker and Anderson tell it, a notoriously violent Party member named George Sams was sent to New Haven by the New York City branch to find out if the Connecticut branch had been infiltrated by FBI spies. “Crazy George,” as he was known, “had a bad reputation, including stabbing a party member in Oakland, and allegedly raping a member of the New York chapter.” He had been expelled for a brief period, but then readmitted. Even so, both the NYC and New Haven chapters deferred to his judgement, and if Sams made an accusation, it was assumed to be true.

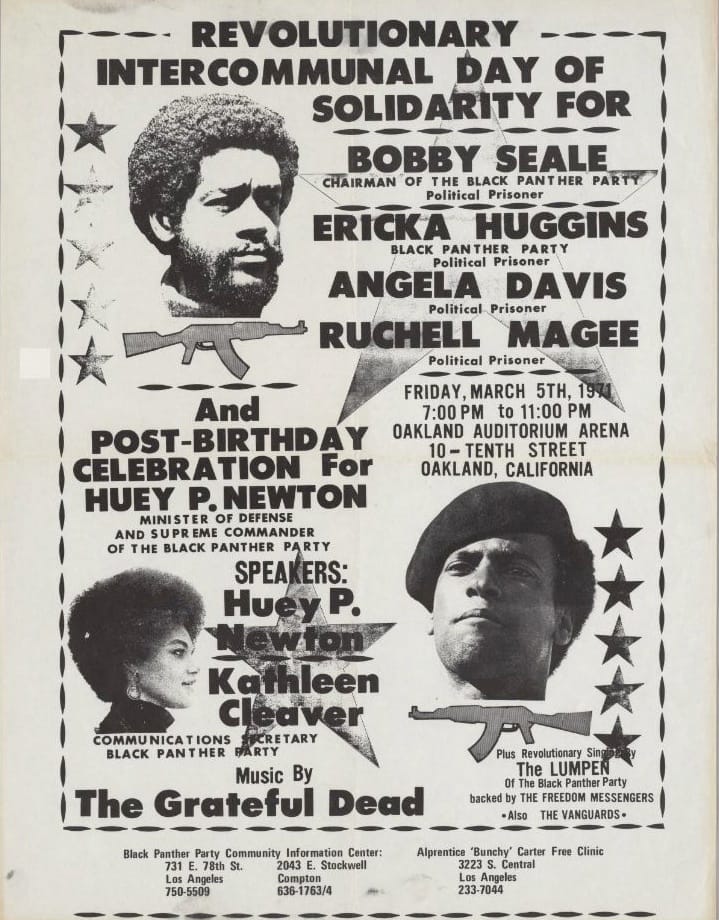

Accompanying Sams was a young new member named Alex Rackley. Two days after they arrived, on May 19th, 1969, the Panthers “tortured Rackley—tying him to a bed, beating him, and scalding him with boiling water. After a day of torture, Rackley confessed—even though he was not actually a spy.” The following day, they drove him to a river, where they shot and killed him. When his body was discovered, the police arrested 14 New Haven Panthers, including the chapter’s prominent female leader, Ericka Huggins. Sams had secretly recorded Rackley’s torture in order to terrify any other members tempted to collaborate with the authorities. That recording allowed the prosecution to prove that it was Huggins who had conducted the interrogation.

Sams fled to Canada. When he was caught, he told police that Bobby Seale had ordered the torture and killing a day earlier, and that he had only been following orders. Seale and Huggins were then tried together for murder in October 1970, but the jury failed to reach a verdict and the presiding judge dismissed the charges on May 25th, 1971. But then Walker and Anderson imply that it was FBI agents—including possibly George Sams himself—who were at fault, and that the incident was part of a “Cointelpro action meant to discredit the Panthers and jail key leaders like Seale and Huggins.” No good evidence was ever obtained in support of this allegation; even if Sams had been working for the Bureau, the Panthers raised no objections to his orders and made no effort to substantiate what they considered to be capital charges before carrying out the death sentence.

The interrogation, torture, and murder of Rackley reveals the shocking reality of what the group really was—a radical and violent cult, the members of which were prepared to go to extreme lengths at the behest of its leaders if they thought it served their revolutionary goals. The authors’ attempt to blame the Panthers’ actions on the FBI is a whitewash of their ruthless and fanatical cruelty, and ignores the fact that the Panthers had coerced a confession from a terrified and innocent young man. A more accurate account can be found Michael Moynihan’s Daily Beast essay:

When his captors uncinched the noose around his neck and shoved him into a wooden chair, Alex Rackley might have assumed his ordeal was over. He had already endured a flurry of kicks and punches, the repeated crack of a wooden truncheon, ritual humiliation, and a mock lynching. But it wasn’t over. It was about to get much, much worse.

Rackley, a slight, 19-year-old black kid from Florida, was tough (he had a black belt in karate), but hardly in a position to resist his psychopathic interrogators. During a previous beating he had gamely tried, kicking and flailing and swinging his arms. But this time he was tied to the chair, with a towel stuffed in his mouth to mute the screams. The women upstairs were tending to the children while assiduously preparing pots of boiling water—because traditional gender roles applied in the torture business, too.

When the bubbling cauldrons were brought to the basement—four or five of them—they were thrown over Rackley’s naked body. Then they worked him over some more. With him burned, battered, and bloodied, the towel was removed from his mouth. As a warning to those who would sell out the party to the Feds (“jackanapes,” “pigs,” and “faggots,” in the party’s nomenclature), the Lubyanka-style proceedings would be recorded on half-inch tape.

Moynihan goes on to quote from the tapes played at the trial and relates how “coolly and dispassionately” Ericka Huggins read the previous interrogation session into the record. Rackley, she declared, “was either an extreme fool or a pig, so we began to ask questions with a little force and the answers came out after a few buckets of hot water … then the brother got some discipline in the areas of the nose and mouth.” Rackley was then tied to a bed and when they next came to see him, he was covered in his own excrement and urine. They bundled him into a car with his hands tied and a noose around his neck made from a wire coat-hanger and drove to the Coginchaug River in Middlefield, Ct. There, he was executed by Warren Kimbro and Lonnie McLucas on the orders of George Sams, who told the group that the national leadership had given the order to “ice him.”

The uncritical hosannas the Panthers are currently enjoying are strange, not least because the truth about the organization’s thuggery, violence, murder, and phoniness has been well-documented for years. The earliest of these was a blistering exposé by Berkeley-based journalist Kate Coleman, published by New Times magazine in 1978. The Black Panthers, Coleman concluded…

…have committed a series of violent crimes over the last several years. Now, disaffected Panther Party inmates and others have told New Times about the scope and nature of this violence—about arson, extortion, beatings, even murder. There appears to be no political explanation for it; the Party is no longer under siege by police, and this is not self-defense. It seems to be nothing but senseless criminality, directed in most cases at other blacks. There is even a secret wing of the Panthers, known within the Party as “the Squad” to administer the brutality. And at the center of it all is Panther founder Huey P. Newton.

Coleman had to flee abroad to escape threats of revenge from former Panther loyalists, who she feared would find and possibly murder her. Huey Newton, as one might expect, personally attacked the piece as evidence of the US Government’s vendetta against him. He announced his intention to sue Coleman and New Times for over $6 million, an empty threat he never pursued.

Then in 1990, Peter Collier and David Horowitz added a chapter about Huey Newton entitled “Baddest” to a new edition of their 1989 book, Destructive Generation: Second Thoughts About the Sixties. During his radical youth, Horowitz had been a passionate supporter of the Panthers; he had raised money for them and met regularly with Newton, who made him an adviser. But as time passed, he came to understand the truth about the group’s character and activities, and in the revised and updated edition of their book, he and Collier provided the most complete account of Newton’s life and leadership of the BPP then available.

They revealed that after a shootout with an Oakland cop Newton killed, he lived in two worlds, in which “the boundaries between violence and good works, crime and politics” became blurred. Before long, he began to demand protection money from liquor stores, “strong-arming after hours clubs,” as well as pimps and drug-dealers. During the days of 1974, he ran the Panther school and played the part of the Marxist intellectual for his white supporters, while at night he beat up enemies with the aid of his bodyguards, and entered bars with guns drawn, chanting “Castroite rants” and telling the customers “I Am the Supreme Servant.”

Building on the revelations in the Collier-Horowitz book, the late African American journalist Hugh Pearson wrote an indispensable account entitled The Shadow of the Panther Huey Newton and the Price of Black Power in America, which was published to rave reviews in 1994. Indeed, two of those reviews appeared in the New York Times before the paper of record surrendered its editorial judgment to BLM-inspired radical chic. A review by Christopher Lehmann-Haupt printed on June 30th was followed by a front-page piece in the paper’s influential weekly book review by Bob Blauner 10 days later. Pearson, Lehmann-Haupt noted…

…has dug up extensive evidence of the corruption of the Panther leadership, which went from mistreatment of female members to such outright crimes as extortion, drug dealing, misappropriation of funds and murder. And he has charted Newton’s own moral disintegration, which left him a paranoid, despotic drug addict who killed subordinates at a whim, who boasted of shooting the police officer for whose murder he was acquitted on a technicality and who was himself finally shot to death on Aug. 22, 1989, by drug dealers apparently fed up with being shaken down for free crack cocaine.

He concludes that Pearson had offered “a richly detailed portrait of a movement most of us were aware of only from intermittent sensational headlines that bounced us from shootouts to show trials.” Pearson’s exposure of the Panthers’ darker side offers a sobering contrast to the sentimental picture now painted by credulous journalists and filmmakers of radical philanthropic social justice activists given to justifiably strident rhetoric. As Blauner notes:

Expecting to write a history in which “the beauty of its breakfast programs, its communal theories and so on far outweighed the negative,” Mr. Pearson instead uncovered a chilling tale of an organization that relied overwhelmingly on terror to further its goals and control its membership. Most disturbing are his accounts of the routine use of violence—intimidation, extortion, beatings and torture—against members and former members. Murder, Mr. Pearson indicates, was not uncommon. Despite a supposedly anti-sexist ideology, sexual harassment was the rule. So was the abuse of party finances. Mr. Pearson even argues that the Panthers’ much-publicized shoot-outs with the police were planned in advance by the party itself, which maintained an impressive arsenal of sophisticated military equipment. The picture that emerges is that of an African-American Mafia. (Newton was so taken with the movie The Godfather, Mr. Pearson tells us, that he saw it repeatedly and urged his comrades to do likewise.)

Before he was murdered, Huey Newton admitted to a friend that he was proud of the crimes he had got away with, including the pistol-whipping of a tailor, the cold-blooded killing of a prostitute, and the unprovoked murder of a white Oakland police officer. He was also proud of how many celebrities worshipped him and came to his aid, particularly the Hollywood producer Bert Schneider, who gave him money and bought the lavish penthouse in which the BPP leader lived, supposedly to avoid attacks from enemies.

Gullible benefactors like Schneider and other wealthy supporters no doubt enjoyed the frisson of transgressive glamor produced by association with fiery revolutionary cant, but the group’s lurid propaganda also misled its supporters about the urgency of its moral mission. After the murder of Fred Hampton, the Panthers’ lawyer Charles Garry claimed that 28 Panthers had been “murdered” by the police in 1968 and 1969 as part of a campaign of “genocide.” However, an investigation by legal journalist Edward Jay Epstein published in the New Yorker in early 1971 (and reported by Paul L. Montgomery in the New York Times) revealed that Garry’s claims were gross exaggerations, if not entirely false.

Pressed to substantiate this claim, Garry reduced the figure of Panthers killed to 19, and then acknowledged that only 12 of those 19 had died in confrontations with the police—the remainder, Montgomery reported, were committed by “members of a rival black organization, by a merchant who claimed he was being held up, and by unknown persons.” Even that did not turn out to be true. As Montgomery’s report continued:

Mr. Epstein found that of the 12 victims finally cited by the lawyer [Garry], two did not involve the police. He said one victim was killed by his wife after a domestic fight and another—Alex Rackley—was, according to confessions, murdered by members of the Party. In the remaining ten killings, with the exception of the Hampton case, Mr. Epstein found that the police had probably acted in self-defense.

For some reason, the Panthers’ hypersensitivity to American racism and social injustice at home did not preclude them from running interference for some of the late-20th century’s most barbaric despotisms abroad. The BPP’s leaders were particularly fascinated by Marxist-Leninist ideology which they believed explained and justified their entire movement. They defiantly proclaimed this allegiance and instructed their members and readers of their newspaper in the glories of Communism. When Angela Y. Davis, then a leading California member of the CPUSA, became involved with the BPP in the early 1970s, she persuaded the Communist Party to merge its fight against racism with that waged by the Panthers, thereby cementing the link between the BPP’s black nationalism and Communist ideology.

The Panthers were, as Michael Moynihan explained, “ideological fanatics.” The Party’s official newspaper, The Black Panther, told its readers that it was guided by “the revolutionary works of Marx, Engels, Lenin, Stalin, Chairman Mao, Comrades Kim Il Sung, Ho Chi Minh, Che Guevara, Malcolm X, and other great leaders of the worldwide people’s struggles for liberation.” They were, the Party announced, “black revolutionaries who are fighting this racist imperialist faggot honky.” Anyone who bothers to read the paper’s back issues will find odes to some of the absolute worst of the communist regimes, including tributes to Enver Hoxha, the Stalinist who led the “People’s Republic of Albania.”

BPP leaders, in their various contributions to the paper, would regularly cite the words and example of Stalin himself. “Our party,” wrote Bobby Seale, “can see Lenin and Stalin when we want to understand Huey [Newton] and Eldridge [Cleaver].” It should not be surprising that when Cleaver fled the United States to evade arrest, he went first to North Korea before taking refuge in Algeria, where he appeared in a propaganda film with Robert Scheer, praising Kim Il-Sung’s Marxist ideology of juche, or self-reliance. (I saw the film when it was first shown in the United States.)

Looking back through issues of the Panthers’ newspaper, I found an amazing full-page article in the March 9th, 1969, issue entitled “Mao-Tse Tungs [sic] Thoughts Guide Surgeon in Severed Arm.” It reported that a young and inexperienced surgeon had successfully performed the operation without the necessary medical equipment at a small local hospital, far from Beijing. The patient, a member of the Red Guards, thanked Chairman Mao whose “brilliant thought guided the hearts and minds of the surgeons in rejoining my hand.” On the facing page, a headline proclaimed: “U.S. Imperialism: The Source of All Evil.”

In the March 13th issue, Eldridge Cleaver filed a dispatch from North Korea entitled “Manifesto from the Land of Fire and Blood,” in which he attacked South Korea’s “vicious railroading” of a pro-North Korean man, which he compared to the “railroading of Huey P. Newton, Bobby Seale, the Chicago 7—through the pig courts of Babylon.” He then introduced his manifesto of the “Revolutionary Party of Unification”—the name of a group in the South funded by the North’s regime—to “show solidarity with our Korean brothers” and prevent “the pig government [of the United States that] will have us all involved in another cruel war” like the one in Vietnam. The following two pages of the paper reproduced the manifesto, which called for a unified Communist Korea under Kim Il-Sung’s leadership.

In 1970, Tom Wolfe wrote a landmark essay for New York magazine entitled “Radical Chic: That Party at Lenny’s,” in which he mocked Leonard Bernstein and the fabulously wealthy socialites who attended his absurd fundraiser for the Black Panthers. Forty-six years later, Beyoncé’s dancers performed in Panther-style berets at the Super Bowl, to show that she too understands the authenticity of the black experience and struggle.

But Hugh Pearson, like Wolfe before him, saw through the perverse vanity of such posturing and understood the power of ideological myth-making to disfigure history. “The radical left and the left-liberal media,” he wrote, “continued to play a major role in elevating the rudest, most outlaw element of black America as the true keepers of the flame in all it means to be black.” Pearson sadly took his own life a few years after the book’s publication, but were he alive today, he would undoubtedly recoil from the adulation lavished upon the group by those who either haven’t bothered to read his research or have seen fit to simply disregard it.

Like David Horowitz, Bob Blauner had once been a Panther supporter. He wrote about the group favorably, and when Newton was tried for murder, he even joined the defense team. But when he read Pearson’s book, he was forced to acknowledge that he’d been duped and revised his position accordingly. Like so many others, he “did not want to believe that such a militaristic methodology might indeed have fascistic implications. The rationale that we didn’t know what was happening is lame. That excuse has been heard before. The truth is that we didn’t want to know.”