Books

In Praise of the Novelization—Pop Fiction's Least Reputable Genre

This month brings us the release of Quentin Tarantino’s Once Upon a Time in Hollywood. No, not the film. That came out in 2019. But now HarperCollins is publishing a novelization, written by Tarantino himself, and based on the earlier film. This particular type of fiction—the bastard offspring of the film treatment and the legitimate novel—is probably pop fiction’s least reputable genre, which no doubt is why it appeals to Tarantino. When HarperCollins announced the project last fall, Tarantino issued a statement saying:

To this day I have a tremendous amount of affection for the genre. So as a movie-novelization aficionado, I’m proud to announce Once Upon a Time in Hollywood as my contribution to this often marginalized, yet beloved sub-genre in literature. I’m also thrilled to further explore my characters and their world in a literary endeavor that can (hopefully) sit alongside its cinematic counterpart.

Movie novelizations have been around since filmdom’s silent era and are still a fairly common sight on the paperback spinner racks of chain bookstores and airport gift shops. The genre is often looked down upon as a literary backwater, attracting only hacks and whores. Tarantino’s affection can probably be at least partially attributed to the year of his birth—1963. Those of us born into the so-called Baby Boom generation grew up before videocassette players were widely available (and before DVD players and streaming services had even been conceived). Back in those benighted days, if you enjoyed a film based on an original screenplay and you wanted to experience it again after it had left the theater, your options were limited. You could wait for it to appear on television (where it would almost certainly be shortened, censored, cropped from its original aspect-ratio via pan-and-scan technology, and chock-full of commercial breaks), you could hope for it to enjoy a theatrical revival (highly unlikely), or you could seek out a novelization, which, though it would lack the colorful visuals and the musical score and the performances, would at least allow you to be thrilled once again by the plot and the dialogue, or some semblance thereof. Furthermore, although theaters wouldn’t allow people under 16 to see an R-rated film without parental accompaniment, bookstores had no such restrictions. A kid could buy the novelization of an R-rated movie without the book clerk asking to see his ID.

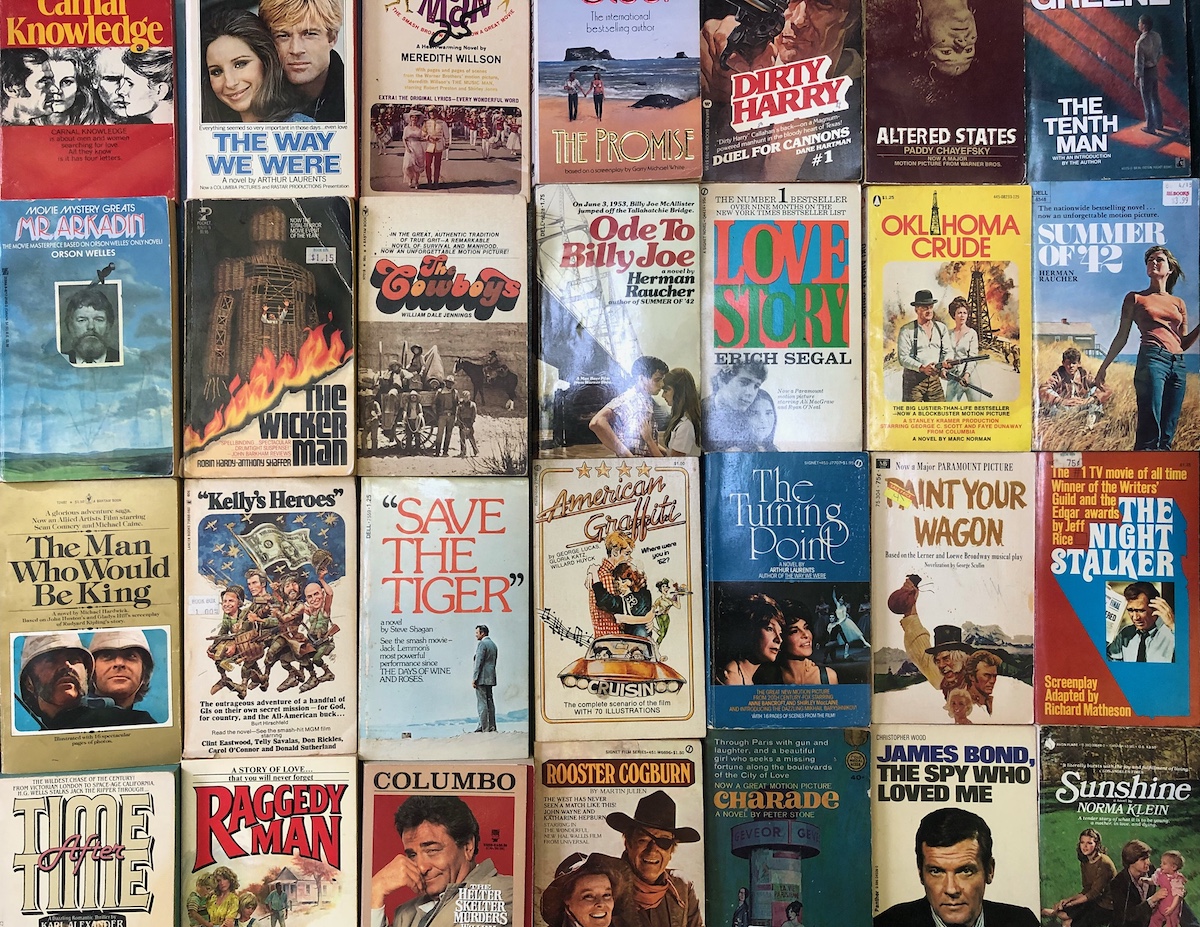

The 1960s and 1970s were probably the golden age for both the TV and movie novelization, at least in terms of sheer numbers. I was a young book-lover back then and I can recall spinner racks filled with novelizations of dozens of successful—and a few not-so-successful—TV series. Leave It To Beaver, Ironside, The Man From U.N.C.L.E., Starsky and Hutch, Time Tunnel, Star Trek, Hawaii 5-O, Mannix, The Prisoner, I Spy, Get Smart, The Partridge Family, The Mod Squad, Rat Patrol, The Brady Bunch, Batman, Columbo, Dark Shadows—the list goes on and on. Some of these books (such as the adaptations of Star Trek episodes written for Bantam Books by James Blish) were based on actual episodes of the program, but many contained original stories that employed the TV show’s characters and settings and themes.

There’s a lot of talk about cinematic universes these days, but novelizations were expanding those universes even before the concept had a name. Casual fans of fictional San Francisco homicide detective Harry Callahan are probably familiar with the character only through the five films in which he has appeared, Dirty Harry (1971), Magnum Force (1973), The Enforcer (1976), Sudden Impact (1983), and The Dead Pool (1988). But superfans will also be familiar with Duel for Cannons, Death on the Docks, Massacre at Russian River, and the nine other spin-off novels in which Harry’s story was expanded by “Dane Hartman” (a pseudonym used by a collective of authors).

Sometimes the novelizers took famous TV or movie characters and sent them off in surprising new directions. According to Lori A. Paige’s study The Gothic Romance Wave: A Critical History of the Mass Market Novels, 1960–1993, author Marilyn Ross (real name: Dan Ross) wrote a phenomenally successful series of Dark Shadows tie-in novels without ever having watched the program, a gothic daytime soap opera that ran from 1966–71. His ignorance of all but the barebones outlines of what the show was about allowed him to create a Barnabas Collins (the vampire whose exploits eventually became the focus of the series) who differed greatly from the one portrayed by Jonathan Frid on the TV screen. Writes Paige, “[L]iterary Barnabas is nowhere near as frightening” as TV Barnabas:

He is a gentleman on every page, a tragic soul yearning for a lasting love his curse prevents him from attaining. He is described (repeatedly, in fact) as a handsome and articulate man, a welcome guest at any party, a patron of the arts … Dan Ross admitted in interviews with Dark Shadows fans, conducted long after the series ended, that he had little interest in following the scripts from the show. He decided to strike out on his own, creating new characters and situations. He was interested in exploring avenues the show could not due to time, cast, and budget constraints.

Doctor Who appears to be the all-time champion of TV show novelizations, having generated hundreds of them. Curiously, British publishers sometimes hire a Brit to write a movie tie-in book even though an American author has already done the job. Thus, the UK novelization of Peter Hyams’s 1978 thriller Capricorn One was written by Ken Follett (using the pseudonym Bernard L. Ross), while the American novelization was written by Ron Goulart.

A few gifted authors occasionally deigned to write a novelization of a film or TV series. Beverly Cleary, the highly regarded children’s author who died earlier this year at 104, once wrote a Leave It To Beaver spin-off (coincidentally, her name was a near-anagram of the show’s main character, Beaver Cleaver). Sometimes novelizations served as a writer’s springboard. Early in her career, Danielle Steel, the fourth bestselling fiction writer of all time, novelized Garry Michael White’s screenplay for the 1979 film The Promise. Sometimes novelizations served as a sad swan song. Late in his career (and life), legendary crime writer Jim Thompson wrote a spin-off novel for the TV series Ironside. He also wrote novelizations of the films The Undefeated (1969) and Nothing But a Man (1970). Paul Monette, who won the 1992 National Book Award for his memoir Becoming a Man: Half a Life Story, novelized several films in his too-short life, including Scarface (1983), Predator (1987), and Midnight Run (1988). William Kotzwinkle, author of numerous novels, including the World Fantasy Award-winning Doctor Rat (1976), wrote a novelization of Melissa Mathison’s screenplay for E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial. It turned out to be the bestselling work of fiction in America for 1982. Pulitzer Prize-winning film critic (and novelist) Stephen Hunter wrote a novelization of Arthur Penn’s 1985 film, Target.

Graham Greene’s novella The Third Man is a novelization of sorts. He sketched it out merely as a précis of a film script he wanted to write, which he had no intention of publishing. But Carol Reed’s 1949 film became a hit (in 1999, the British Film Institute voted it the best British film of all time), which encouraged Greene to make his novella available to the reading public (the novella differs in some important ways from the film). Likewise, Greene’s novel The Tenth Man began life as a film treatment he wrote in the 1930s and quickly forgot about. At some point MGM acquired the rights to the treatment but then decided not to make a film from it. They sold the rights to a British publisher who gave Greene permission to convert the treatment into a novella, which he did. The book was published in 1985 and then adapted into a 1988 TV movie starring Anthony Hopkins and Kristin Scott Thomas. William Saroyan’s novel The Human Comedy started out as a 240-page script for a film that Saroyan hoped to direct himself. When MGM dropped him from the project, he novelized the script and sent it off to Harcourt, his publishers. The novelization made it into American bookstores just a month before the film made it into American movie theaters and became the fifth bestselling work of fiction of 1943. The film earned Saroyan an Academy Award for Best Story, a category that no longer exists. A much fuller list of novelizers, famous and not, can be found in Randall D. Larson’s excellent 1995 tome, Films Into Books: An Analytical Bibliography of Film Novelizations, Movie, and TV Tie-Ins. It is the only full-length academic study of the genre I’ve ever come across, and it is not nearly as pretentious as the subtitle makes it sound.

Unfortunately, Larson’s book covers only acknowledged novelizations, whereas one of the most interesting sub-categories of the genre is the stealth novelization. This type of book pretends to be the source of a film when it is actually its byproduct. Herman Raucher wrote the first draft of the screenplay that would eventually become Summer of ’42 (1972) back in the 1950s but could never find any takers for it. In the late 1960s, he showed it to filmmaker Robert Mulligan (To Kill a Mockingbird), who eventually got Warner Bros. studios to greenlight a movie from it. According to Wikipedia, here’s what happened next:

After production, Warner Bros., still wary about the film only being a minor success, asked Raucher to adapt his script into a book. Raucher wrote it in three weeks, and Warner Bros. released it prior to the film to build interest in the story. The book quickly became a national bestseller, so that when trailers premiered in theaters, the film was billed as being “based on the national bestseller,” despite the film having been completed first. Ultimately, the book became one of the best selling novels of the first half of the 1970s, requiring 23 reprints between 1971 and 1974 to keep up with customer demand.

Something similar happened to Erich Segal. In the late 1960s, he wrote a screenplay about a young female student at Radcliffe and a young male student at Harvard who fall in love only to discover that the young woman is terminally ill. Paramount Pictures purchased the screenplay but asked Segal to write a novelization of it in order to drum up interest in the film. Segal complied and the result was Love Story, the slim novel (novelization, actually) that became the bestselling work of fiction in America for 1970.

In 1976, five years after his impressive work on the Summer of ’42 novelization, Herman Raucher pulled off an even more impressive feat—he novelized a pop song! It seems that Max Baer Jr. (best known as the actor who played Jethro Bodine on The Beverly Hillbillies) had become determined to make a film out of Bobby Gentry’s spooky 1967 ballad, Ode to Billy Joe, and he hired Raucher to write the script. The notoriously cryptic song has a running time of four minutes and fifteen seconds and contains all of 358 words. Somehow Raucher turned it into a respectable screenplay that, when filmed, had a running time of an hour and 45 minutes. He also converted it into a literate and entertaining 253-page novelization.

Neither Raucher’s Summer of ’42 nor Segal’s Love Story was actually labeled a novelization by its publisher. Rushing out a short novel in advance of a film in order to drum up interest in the film’s release was a fairly standard practice back in the1970s. The practice appears to have largely died out since then, probably because today’s pop cultural consumers are a lot savvier than their parents and grandparents were. In the 1970s, such stealth novelizations were commonplace and fairly easy to spot if you knew what to look for. Most (but certainly not all) of them were paperback originals (meaning that no hardback edition was ever issued). Most of them were well under 300 pages (240 pages seems to have been the genre’s sweet spot). Stealth novelizations were almost always written by the author of the film’s screenplay and usually arrived in bookstores just a few weeks, or perhaps a few months, before the film version arrived in theaters. Stealth novelizations were never identified as such—their cover copy either identified them as “novels” or offered no genre identification at all.

Consider, for instance, Marc Norman’s novel Oklahoma Crude. My paperback edition, which is 240 pages long, is a tie-in to the Stanley Kramer film of the same name, starring George C. Scott and Faye Dunaway. The copyright page says 1973. The film was released in July of that year. The archived review of the book at the Kirkus Reviews website mentions that a Stanley Kramer film is already in production. Even in 1973, Marc Norman (who would later share a Best Original Screenplay Oscar with Tom Stoppard for the 1998 film Shakespeare in Love) was already working as a writer of teleplays and screenplays and had no published novels to his name. Norman’s entry on Wikipedia asserts (without citing a source) that his screenplay for Oklahoma Crude came first and that the novel was adapted from it. If this is correct, then it gets my vote for greatest stealth novelization of all time—a small comic masterpiece reminiscent in some ways of Charles Portis’s True Grit.

Another excellent stealth novelization is The Cowboys, a 1971 western written by William Dale Jennings and based on a film treatment he had already sold to Warner Bros. The book, like the 1972 film version starring John Wayne and directed by Mark Rydell, is set in Montana in 1877 and tells the story of rancher Wil [sic] Andersen (Wayne), whose ranch hands abandon him en masse to go prospecting for gold just before a 400-mile cattle drive. It being summertime, the town’s young boys (all of them between 13 and 15 years old) are out of school and largely idle, so Andersen, despite misgivings, decides to train them to replace his cowhands. The movie was as straight as an arrow, but the novelization differed in an important respect.

Jennings was a fine writer best remembered today for having been a fierce advocate of gay rights long before the Stonewall Uprising of 1968, and his novel contains homoerotic touches that never would have made it into a John Wayne western of the 1970s (or any other era). The most prominent female in the book is Miss Dulcy Drew, a prostitute whom Jennings slyly suggests is probably a man in drag. In an afterword, Jennings notes that one of the reasons he wrote The Cowboys was to explore what men did to slake their sexual urges on cattle drives, when they might go weeks or months without seeing a female. “Western historians and Hollywood would have us believe that erectile tissue was completely missing in the metabolism of the West,” he writes. He describes the aftermath of a naked swim the boys take together like this:

They stood on the river bank and peeked at one another with secret interest … Inevitably comparing their bodies, they were envious of some and proud before others … But it was Horny Jim who received the most comment. He was almost ludicrously lucky. They laughed and kidded him and he was delighted. “My father says you don’t get your full growth until you’re eighteen or so. Think how big I’ll be in four more years!”

Later in the novel, when the boys go bathing together one last time, they’ve begun maturing from boys to men:

Bathing in the river, they again compared the jewelry of their groins and that peculiarly male thing, their hair: how dark on the crotch, how thick on the chest, how bristly on the chin.

John Wayne’s image adorned the paperback edition of The Cowboys, which was one of the most widely distributed homoerotic novels of the early ’70s. Presumably, the Duke was blissfully unaware of this fact. Unlike Wayne, who noisily supported every American war but bent over backwards to avoid serving in any of them, Jennings served in World War II, fought at Guadalcanal, and earned multiple medals for his valor. Jennings’s patriotism was the real deal; the Duke’s was more in the spirit of a cheap movie tie-in. In today’s neo-Puritan culture, a book like The Cowboys would likely be condemned for its frank portrayal of adolescent sexuality and its use of racial slurs. But back in the 1970s, it was just another piece of pop fiction on the local supermarket spinner rack. I managed to read it aged 13 without being turned into a child molester or a Klansman.

But was The Cowboys really a novelization and not a novel? The opening credits of the film claim that it is based on the book by William Dale Jennings. Jennings shares the screenwriting credit with two other men. Wikipedia (not always the world’s most reliable source of information) claims the novel derived from Jennings’s film treatment. Is this true? A clue can be found in the back of the book, where Jennings confesses to having made a mistake in historical accuracy. It turns out that, in the 1870s, Montana children only attended school during summer because it was too cold in the winter months. But, writes Jennings, by the time he discovered this error, “the publisher, film producer, and writer were quite unwilling to scrap the whole project just because this one point made the story impossible.” This suggests that the book was being written while the film was being made, and so the script must have predated the novel. The hardback edition of the book was published in September of 1971. The film was released in January of 1972. The movie tie-in paperback came out the following month. That tight chronology suggests a stealth novelization to me. What’s more, if the book, in all its homoerotic glory, had come first, it seems unlikely that any American studio would have considered it appropriate source material for a John Wayne film. I suspect Jennings sold the much tamer screen treatment to Warner Bros. first and then subversively transformed it into a raunchy sausage-fest during its novelization.

Sometimes a novelization’s path to publication has as many twists and turns as its plot. In 1966, a 26-year-old British writer and actor named David Pinner set out to write a screenplay about a cop investigating a ritualistic murder. He titled the screenplay “Ritual.” Film director Michael Winner liked the script and wanted to make the film. Pinner’s agent, however, suspected that the screenplay might get trapped in development hell for years and recommended that his client convert it into a novel instead. So, Pinner spent seven weeks novelizing the story. The novel was published in 1967. In 1971, it caught the attention of writer Anthony Shaffer, best known then for his 1970 stage play Sleuth. At that time Shaffer and actor Christopher Lee were looking for an intelligent horror story that they could turn into a film. After reading and liking Ritual, Shaffer and Lee paid David Pinner £15,000 for it, and Shaffer went to work transforming it into a screenplay—which is what it had been originally. But Shaffer quickly decided that Ritual wouldn’t work as a film. Instead, he opted to write an original screenplay incorporating just some elements of Pinner’s novel. Shaffer called this new story The Wicker Man.

The tortuous path that Shaffer and director Robin Hardy traveled to bring The Wicker Man to the screen is the subject of numerous articles and a number of full-length books, including The Quest for The Wicker Man, edited by Benjamin Franks and Jonathan Murray, and Inside The Wicker Man: How Not To Make a Cult Classic, by Allan Brown. The film was released in Britain in 1973, but only after Hardy had been forced by the studio to remove nearly 20 minutes from his preferred cut. Fortunately, the film became a big enough hit that, a few years later, Hardy and the studio decided that a fully restored director’s cut might be able to find an audience. Alas, the studio had thrown out all the copies of the original cut but one. Early in the process a lone copy of the longer version was sent to American horror film impresario Roger Corman, to see if he might be interested in distributing it in the US. Corman had passed on the distribution rights but he had hung on to his copy of the film. Thus, a fully-restored director’s cut was made for re-release in January 1979. At that point, Shaffer and Hardy decided that a novelization of the film, published slightly ahead of the film’s re-release, might help drum up publicity for the re-edit. So, together they cranked out a tie-in novel of 240 pages. This book was a novelization of a screenplay that had been inspired by a novelization of another screenplay.

This type of cross-pollenization of intellectual property isn’t at all unprecedented. In the 1970s, Christopher Wood wrote novelizations of the scripts he contributed to the James Bond films The Spy Who Loved Me (1977) and Moonraker (1979) despite the fact that both films were based (loosely) on existing novels written by Ian Fleming. There are fans online who prefer the Wood novelizations to the Fleming originals. Likewise, it isn’t unusual to find people online who prefer a novelization to the film it is based on. For instance, there seem to be a lot of fans who prefer James W. Ellison’s novelization of Finding Forrester to Gus van Sant’s 2000 film version (written by Mike Rich and starring Sean Connery). A possible explanation for this phenomenon is that novelizers are often working from a very early draft of a screenplay, and early drafts are almost always more straightforward and less convoluted than rewrites. Hollywood screenplays often grow more complex for reasons that have nothing to do with story logic.

For instance, Arthur Laurents’s original script for The Way We Were (1973) focused mainly on the character of political activist Katie Morosky (played by Barbra Streisand in the film). Her sometime-boyfriend Hubbell Gardiner was a secondary character. When director Sidney Pollack brought his friend Robert Redford on board to play Hubbell, they insisted that the Hubbell character be given equal stature with the Katie character. Laurents resisted so Pollack elbowed him out of the film’s development process and brought in 11 different writers, including Dalton Trumbo and Paddy Chayefsky (about whom, more in a moment), to tinker with the script. The result was a bloated mess. Though no literary masterpiece, Laurents’s novelization of the film is based not on the shooting script but on the 125-page treatment he had drafted early in the process in order to sell the project to producer Ray Stark. As a result, it is much more coherent than what Pollack managed to put up on the screen.

So, Quentin Tarantino isn’t the only prestigious name connected with the lowly literary product known as the novelization. In fact, he isn’t even the only highly regarded film director to have novelized one of his own films. In 1994, New Zealand filmmaker Jane Campion co-wrote, with Kate Pullinger, a novel called The Piano, which was essentially a novelization of her 1993 film of the same name, for which she had won an Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay. Steven Spielberg novelized his script for Close Encounters of the Third Kind (with an uncredited assist from Leslie Waller). Filmmaker Whit Stillman has written novelizations of his 1998 film The Last Days of Disco and his 2016 film Love & Friendship (itself based upon Jane Austen’s novel, Lady Susan). In 1978, the great filmmaking team of Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger wrote a novelization of their classic 1948 film The Red Shoes. Mexican filmmaker Guillermo del Toro has novelized several of his films, including Pan’s Labyrinth (with Cornelia Funke) and The Shape of Water (with Daniel Kraus). George Romero (in collaboration with Susan Sparrow) wrote novelizations of two of his films, Martin and Dawn of the Dead (both released in 1978). John Boorman co-wrote (with longtime collaborator Bill Stair) a novelization of his 1974 fantasy film Zardoz, which starred Sean Connery. John Milius wrote a novelization of his 1975 film The Wind and the Lion, which also starred Connery. Paul Mazursky co-wrote (with Josh Greenfeld) a novelization of his 1974 film Harry and Tonto, which did not star Connery. This is by no means an all-inclusive list.

One of the most notorious director-penned novelizations is Mr. Arkadin, published in 1955 to tie in with the release that year of Orson Welles’s film of the same title. The novel was credited to Orson Welles, although it was first published in French, a language in which he wasn’t fluent, and distributed only in France. An English translation appeared the following year. In an interview, Welles told director Peter Bogdanovich that he didn’t write the book and had never read it. Nonetheless, when it was reprinted in 1987 as a Zebra Books paperback it was still being credited to Welles, who had been dead for two years by that time. The paperback’s cover announces it as “Orson Welles’s Only Novel!”

Some novelizations are little more than published screenplays, although they’ve generally been stripped of their slug lines (eg: INT. LESTER’S BAR & GRILL – EVENING), which are often replaced by more reader-friendly scene descriptions. The novelization of Rooster Cogburn, a 1975 sequel to the 1969 film version of True Grit, follows this format, although nothing on the book’s cover suggests that it’s anything other than a paperback novel. The paperback tie-in to the film American Graffiti, published in 1973, is also just a screenplay with the slug lines made more reader-friendly (Ballantine Books had the decency to announce this fact on the front cover: “The complete scenario of the film, WITH 70 ILLUSTRATIONS”). Since the name George Lucas meant almost nothing to your average pop-fiction junkie back in 1973, it appears in tiny print on the front cover alongside the names of his co-writers, husband and wife team Gloria Katz and Willard Huyck (frequent Lucas collaborators). But four years later, when the first Star Wars film was released, the tie-in book featured the words “A Novel by George Lucas” in bold above the title, even though it had actually been written by Alan Dean Foster. One of the most prolific novelizers of all time (as well as a writer of his own original works), Foster has written tie-in books for the Star Trek franchise, the Alien franchise, the Terminator franchise, the Transformers franchise, and for a lot of standalone films, including Krull (1983), Starman (1984), and Pale Rider (1985).

Plenty of successful movie musicals also got the novelization treatment back in the 1960s and 1970s, which may seem odd when you consider that musicals are popular primarily because of… well, the music. But George Scullin’s novelization of the 1969 movie musical Paint Your Wagon is actually more charming and witty than the ponderous film upon which it is based, even though the script had been co-written by Paddy Chayefsky, the only person ever to have won three solo Academy Awards for writing original scripts and adaptations. Chayefsky himself was the author of a stealth novelization. His 1978 novel, Altered States, began life as an 87-page film treatment. Daniel Melnick, a producer at Columbia Pictures, saw the treatment and recommended that Chayefsky turn it into a novel first, in order to build interest in the subsequent film. So, Chayefsky—somewhat surprisingly, since he was an iconoclast who hated taking orders from studio suits—complied, though it wasn’t easy.

Chayefsky wasn’t a natural novelist (or even novelizer) and the stress of turning his treatment into a book took a toll on his health. He suffered a heart attack in 1977 while still working on it (coincidentally, the story is about a research scientist who pursues his inquiry into the nature of human consciousness so relentlessly that he nearly kills himself). The book’s protagonist, Edward Jessup, might well have been speaking for his creator when he tells his wife near the end of the novel why he can’t give up the project that is taking such a toll on his mental and physical health: “I think it’s too late. I don’t think I can get out of it anymore. I’ve committed myself to it … It’s a real and living horror, living and growing within me now, eating of my flesh, drinking of my blood.”

Chayefsky finally delivered the book, his only novel, to Harper and Row, and it was published in 1978. The film was expected to follow shortly, but the production was one of the most troubled in Hollywood history, primarily because of interference by Chayefsky himself. Arthur Penn, the original director, walked away after clashing with his writer. The job was then offered to Steven Spielberg, Orson Welles, Sidney Pollack, Robert Wise, Stanley Kubrick, and many other top filmmakers, all of whom turned it down. Ken Russell, who eventually took the job, claimed that he was the studio’s 27th choice. Inevitably, Russell, too, clashed with Chayefsky and had him banished from the set. Chayefsky didn’t want the studio to use his name to promote the film so he took his screenwriting credit under the pseudonym Sidney Aron (his birth name was Sidney Aron Chayefsky). The film, which starred William Hurt and Blair Brown (as well as Drew Barrymore in her screen debut), was finally released on Christmas Day 1980. It was modestly successful at the box office and earned generally positive reviews. But the ordeal had left Chayefsky’s body in a badly altered state. He died a little more than seven months later. He was 58.

For as long as novelizations have been around they have mostly been cranked out in a hurry by hack writers who haven’t spent much time worrying about the quality of the product. Paddy Chayefsky may be the only writer in history whose death can be partially attributed to the effort he brought to bear on this much maligned task. Let’s hope Quentin Tarantino didn’t work that hard on his. He turned 58 in March.

CORRECTION: Due to an editing error, in an earlier version of this article, the authors of the US and UK novelizations of Capricorn One were reversed.