Canada

What Are Dads Good For?

The sadly deflating truth of the matter is that it can take a good few years before children begin to apprehend what fathers are good for.

Last weekend, our lone London, Ontario-residing child somehow got it into her head (and successfully implanted the idea into ours as well) that it was Father’s Day and came over bearing tins of Guinness and a saucy new red wine called Off The Press to join us in a splendid repast featuring the favourite foodstuff of right-thinking fathers everywhere, fish and chips. Realizing that we’d jumped the gun, we joked that we should endeavour to set things right by reconvening on the true Father’s Day this Sunday with my second favourite foodstuff, Chinese takeaway. If that reprise should happen to come off, fine and well. But really, my cup of paternal homage already overfloweth: I think we all recognize that Father’s Day is a sort of poor cousin or add-on jubilee that wouldn’t exist at all if it weren’t for Mother’s Day—rather like Boxing Day is to Christmas.

The sadly deflating truth of the matter is that it can take a good few years before children begin to apprehend what fathers are good for. After nine months of incubation and development in the omni-nourishing mothership, when we naked astronauts get ejected out into the hard cold world (a separation, G.K. Chesterton cannily observed, that is in its way “as solemn a parting as death”) babies remain hardwired to their moms in a way that they never are with their dads. Just the sound of an infant’s cry from another room causes a mother to secrete reciprocal milk. And while the intensity and immediacy of that connection will diminish with maturity, it’s a rare mother who can kill it off for good. I don’t think terrified soldiers dying in battle have ever been known to call out for their dads.

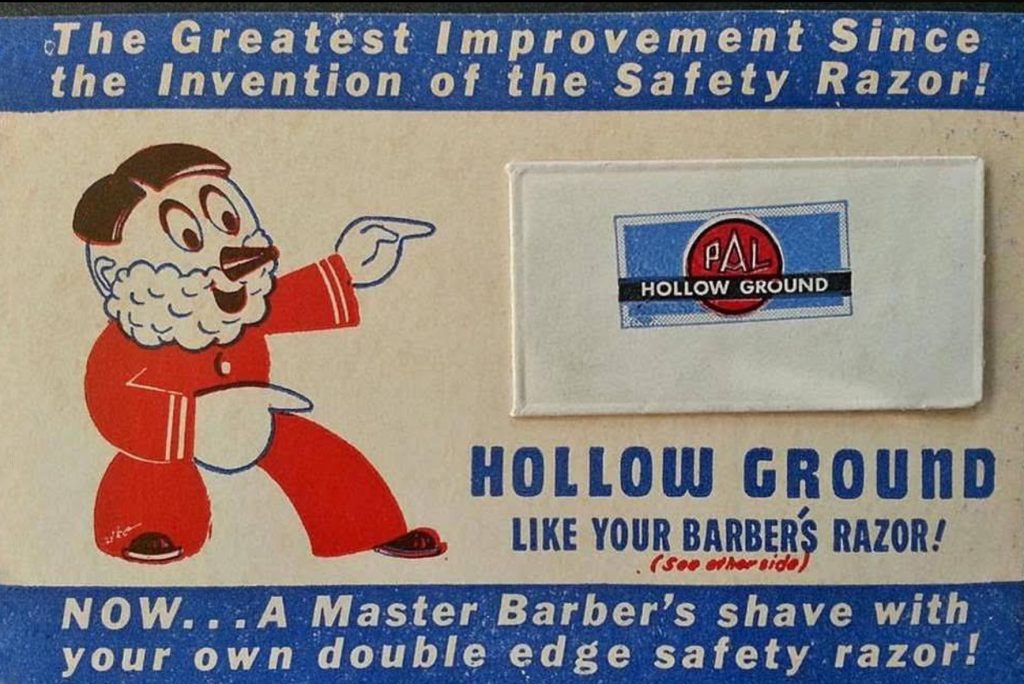

One of the few things I always knew for certain about my own dad was that he shaved. Even before I could formulate words, I’d feel his prickly whiskers whenever we came into close contact. Not so surprising then that when I came to understand that Father’s Day was something I needed to observe, I’d wander down to Dell’s Drug Store and slide a dime across the counter to buy a packet of four single edge, hollow ground Pal razor blades that came in a little box decorated with a cartoon of a guy sporting frothy dollops of white foam all over his chin and cheeks—just like Pops during his early morning ablutions except his latherings were never quite that voluminous.

Gratifyingly, it turned out to be an excellent choice of gift. He was absolutely thrilled with them and told me so every year. “It’s just what I always wanted,” he’d say. So I got him the same thing next year and the year after that and they continued to be rapturously received, though I secretly started to wonder if he wasn’t having me on just a little bit. By the age of about 10 or 11, razor blades started to seem like an inexcusably cheap token by which to pay annual homage to this man who—I’d come to vaguely understand—laboured away five and six days of the week out in the real world as a meat salesman and a butcher (like his father before him) to keep our home afloat. What a hard and thankless row to hoe, that seemed to me from the perspective of pampered youth.

Clearly, it was time to move upmarket, to throw a little more largesse the old boy’s way. Still not knowing what made him tick or what he’d really appreciate as a gift—and still knowing for certain that he did shave—I stuck with the same aisle at Dell’s but zeroed in on aftershave. It was Old Spice if I was feeling flush and Aqua Velva if I was skint. And in the end it didn’t matter which I got because (as I had neglected to notice) Dad didn’t go in for aftershave at all. Maybe it was a generational thing; in the same way that I never pack a bottle of water while my own kids never seem to head out into the world without one. Eventually observing how bottle after bottle would just stack up in the medicine cabinet over the sink, I finally twigged to the pointlessness of acquiring him more facial balms and started buying him books or records instead, some of which, I like to think, might have come reasonably close to addressing his actual interests.

The best Father’s Day gift I ever gave Jack—all of his sons started calling him that when they were in their 20s—was a top-of-the-line pool cue that I inexplicably lucked into and had no use for. He didn’t say it was just what he always wanted. He was too flabbergasted to say anything but “Well, now,” and I knew I’d hit the mark. Jack had a billiard table in the basement where my brothers and I would sometimes shoot a few racks with him whenever we dropped over. He liked to win and if you were gaining on him, he’d tip forward the lamp that hung over the table and ask, “Can you read out how many watts are on that bulb?” Then, your vision messed up by the glare, he’d let the lamp swing back and say, “Never mind. Just take your shot.” Jack also spent a lot of time down there on his own. If you ever dropped by and couldn’t find him, you’d nip downstairs and there he’d be, setting up shots.

Jack’s been gone 17 and a half years now. In the last couple years of his life, he had his own small apartment at Chelsey Park and would spend his days visiting Mom on the Alzheimer’s ward and then make his way through interconnecting halls to his own place where he’d cook (and frequently burn) his supper. We’d often take him out with us when we went grocery shopping, and if we ever lost track of him in the cavernous Metro, we always knew where to find him. The meat coolers at the north end of the store drew him like his basement pool table. Sometimes I wouldn’t approach him right away but would stand there in teary-eyed wonder as he cased out the coolers, comparing the cuts and wincing at the prices, keeping in touch with the trade that had sustained him and the people he loved for almost 90 years.

When (with my wife’s able assistance) I started having kids of my own, I not only learned a lot of life’s very deepest truths in a pretty big hurry, but I saw Jack and the role of fathers generally with new eyes. The clearest illustration of what I mean is to recall the childhood experience of waking up screaming from a nightmare. (Mine, more often than not, involved snakes.) Mom would come and console me, maybe fix up the sheets and say reassuring things, but the moment she was gone, I’d be anxious again and might even fall into part two of the same damned nightmare. She would address my neediness so completely that I wouldn’t quite snap out of it. Whereas with Jack (who’d be the one to come through if I called out a second time), he’d talk about the nightmare a bit, and maybe even make a few jokes about it, which had a wonderful dispelling effect. But crucially, he wouldn’t really address and certainly wouldn’t indulge the neediness. His message—at first glance, a little brusque but ultimately more fruitful—was, “You’re a big boy. You can handle this.”

When our two girls were nine and three, they both had their tonsils removed on the same day. We stood vigil with them in two 12-hour shifts on the day of their operations. My wife went in with them at 7am, saw them off to the operating room and stayed with them when they came to. I went in at suppertime and stayed with them until the next morning. I know my wife had a much rougher go of it. She phoned me at about 4pm with a postoperative progress report and was only able to talk for a couple of minutes because the girls needed her back at bedside. When she left to go home to sleep, their goodbyes were absolutely wrenching. “Please stay, Mom. Let Dad go home.”

I might’ve felt miffed, but I knew exactly what they were feeling. Dads might be better to have around than nothing, but they won’t play endless cajoling games when it’s time to take your medicine. They might play along for two minutes but then they’re going to pour that medicine down your throat whether you’re ready or not. They won’t spoon-feed you ice cream and make encouraging sounds with every wincing swallow. Instead, they pass you the dish and say, “If you eat this stuff up, we can get you out of here in the morning.” In short, dads have what appears to be a relatively shallow well of compassion. They’re interested in how crummy you feel, but they won’t wallow with you in the bathos.

That wallowing is exactly what any child wants in the immediate wake of an operation. But a little further down the road to recovery, dads start to have their uses. Our nine-year-old pretty well bounced back within a week. She came running into the kitchen after her first day back at school to announce she’d eaten some salt-&-vinegar potato chips and they hadn’t hurt at all. Our three-year-old (she of the Guinness and the Off The Press wine) still had a bit of a cold when she went in for the operation and this made for complications that roughly doubled her recovery time. About her 10th night back at home, she woke up crying at 3am. That was usually my shift, but my wife went instead and asked her in those soothing motherly tones, just what was the matter. Her response came back harsh and angry, utterly fed up with this bullshit and wanting no further indulgence. “I want Dad,” she announced and my heart soared.