Activism

Lesbians Aren’t Attracted to a Female ‘Gender Identity.’ We’re Attracted to Women

Two such orientations are heterosexuality and homosexuality. They are defined in terms of specific patterns of attraction.

There is commonly held to be a difference between a sexual preference and a sexual orientation. Sexual preferences include preferences for blondes over brunettes, or macho men over pretty boys. At the more exotic end, they can include predilections for cars, chandeliers, and dalliances with farm animals. None of these are sexual orientations, though. Opinions differ on what makes an orientation an orientation, but my preferred explanation says that for a preference to count as an orientation, it has to be stable in individuals, widespread among the human population, and have a range of relatively important social consequences.

Two such orientations are heterosexuality and homosexuality. They are defined in terms of specific patterns of attraction. You are heterosexual if you, a member of one sex, are stably sexually attracted only to members of the opposite sex to you. Alternatively, if you’re stably attracted only to members of the same sex as you, then you’re homosexual. If you’re stably attracted to both sexes, you’re bisexual. In addition to these terms, equally applicable to both males and females, the English language has words to describe homosexual orientations disaggregated by sex. “Lesbians” are same-sex-attracted females. There are other sex-disaggregated words, too, often pretty negative: “faggots,” “dykes,” etc.

Putting things this way will, I predict, raise the hackles of readers schooled in queer theory, and in particular fans of French post-structuralist Michel Foucault. It is a commonplace there that orientations are—just as biological sex categories are for Judith Butler—socially constructed, historically contingent, and culturally located. As trans scholar Jack (then non-trans Judith) Halberstam summarises approvingly: “Within a Foucauldian history of sexuality, ‘lesbian’ constitutes a term for same-sex desire produced in the mid-to-late twentieth century within the highly politicized context of the rise of feminism … if this is so, then ‘lesbian’ cannot be the transhistorical label for all same-sex activity between women.” My short answer is that, while obviously we need to acknowledge the interesting fact that throughout the ages, same-sex activity has had many different relatively local sociocultural meanings and names, it wasn’t invented in the 20th century. I’m talking about distinctive, relatively ahistorical patterns of sexual relationship in individuals, and not particular cultural representations of that pattern. That’s a coherent distinction to make.

Saying a sexual orientation must be “stable” for an individual doesn’t mean you can’t have voluntary and even pleasurable sexual experiences at variance with it. It’s fairly typical for young people to take a while to figure out what their orientation is, and sometimes it takes older people a while, too. This is more likely for gay people in a culture in which heterosexuality predominates. A gay person might be less willing or even able to notice relevant clues as to where the real patterns of attraction lie. Or a person can just get drunk and have opportunistic sex with whoever happens to be there, against their normal grain. They can have sex with one kind of person, fantasising wildly about another. Or they can be romantically attached to someone in a way that temporarily causes them to seem attractive but wouldn’t otherwise. Strictly speaking, a sexual orientation should be understood in terms of the sex(es) you would be sexually attracted to under relatively self-aware, uncoerced, uninhibited circumstances, and not necessarily who you actually are attracted to right now. A sexual orientation is for life, not just for Christmas parties.

On most plausible models, sexual orientations develop due to factors beyond individual control. Controversy reigns about whether these are genetic or environmental or both, but either way, heterosexuality and homosexuality are not conscious choices. You like sex with the sex(es) you like, and it seems to start quite early on in life. On that basis, it can only be pointless and psychologically damaging to try to change someone’s orientation through what is known as “conversion therapy.” These days, it is accepted by UK professional therapeutic bodies that attempting the conversion of gay people is ethically fraught.

Let’s pause and look at how many times the word “sex” occurred in the characterisations just given of heterosexuality and homosexuality, and remind ourselves, because it can get confusing with so much sex around, that this is “sex” as in male or female and not the copulatory sense. In order to know the sexual orientation—hetero-, homo-, or bi—of person A, you need to know both A’s sex and the sex of the kind of person to whom A is stably attracted. In explaining why someone has the sexual orientation they have, the concept of biological sex is bound to come into the explanation.

Perhaps predictably, then—though still surprisingly, given that they started out fighting for gay rights—this conception of sexual orientation has been rejected by trans activist organisations such as Stonewall and GLAAD. In their view, it’s gender identity, not sex, that makes you a woman or man. This is assumed to have consequences for sexual-orientation concepts such as gay, straight, lesbian, and so on. A “lesbian” is now understood as anyone with a female gender identity attracted to others with female gender identities. This can include biological males as lesbians, as long as they have a female gender identity. Equally, a gay man is understood as anyone with a male gender identity attracted to others with male gender identities. Being straight, meanwhile, is defined as a person with a given gender identity being attracted to someone with an opposite gender identity (albeit that talk of “opposite” doesn’t make much sense in a context in which gender identities are supposed to be multiple and non-binary). The upshot is that sex is irrelevant to sexual orientation.

There seems to me at least one glaring problem with all this: if heterosexual attraction were directed primarily towards gender identity not sex, it would be pretty inefficient in terms of the continuation of the species. If we had to work out someone’s inner gender identity before we knew whom to fancy, we would die out fairly quickly.

In practice, people tend not to insist that they’re attracted to gender identity, but simply to “gender” (and not sex). They say they have a sexual attraction to “Femme” people, or “Masc” people, meaning: to people of either sex who have a stereotypically feminine presentation or masculine presentation. It is implied that assumptions about a person’s sex are irrelevant to such attractions.

But for most, that can’t actually be true, because what counts as a person’s presenting “Femme” or “Masc” changes depending on whether that person is thought of as male or female. For instance: the female model Erika Linder looks very like a young Leonardo DiCaprio—so much so that her break-out photo shoot deliberately depicted her as Leo. But while a young DiCaprio looks relatively feminine for a male, Linder (at least, in that shoot) looks relatively masculine for a female. Even though Linder and DiCaprio have similar-looking features at the physical level, we interpret these features as differently feminine/masculine, relative to accompanying assumptions about their owner’s sex. So even when you think you’re attracted only to someone’s feminine or masculine presentation, perceptions of sex are still playing a significant underpinning causal role in your attraction nonetheless.

This point is reinforced by the findings of a recent survey, in which 12.5 percent of participants indicated they would consider dating a trans person. For nearly half of these respondents, their stated preferences about whom exactly they would date were described by the researchers running the survey as “incongruent.” For instance, roughly two-thirds of the self-described lesbians in the group said they would only date trans men and not trans women, or would at least date trans men as well as trans women. The researchers had assumed that, to be consistent with lesbianism understood in terms of gender identity, lesbians should exclude trans men and include only trans women. The researchers explained these findings as demonstrating “femmephobia.” A less complicated hypothesis would be that lesbians are not stably sexually attracted to males.

i’ve been researching femmphobia all week and if you’d like a run down of what i’m talking about, check out this article https://t.co/biJrDhIN8Z pic.twitter.com/dqk0caXCcM

— sarah schauer 🦂 (@sarahschauer) August 8, 2020

In arguments about the relevance of sex to sexual orientation, three objections tend to come up fast. One is the familiar line: “You can’t see someone’s chromosomes!” That’s like saying you can’t fancy brunettes because you can’t see the melanocytes that create pigment in their hair. Sex tends to be reliably connected to a variety of observable, potentially arousing physical features: look, touch, taste, scent, and vocal sounds.

A second objection goes: are you really saying that a female in a relationship with a gorgeous, feminine, post-surgery trans woman isn’t a lesbian, just because she’s sexually attracted in this case to a male, technically speaking? Equally: are you saying that a man in lust with a hot ripped trans man, post-surgery and hormones, isn’t actually gay? Actually, I’m not. Rather, I’ll say that these sorts of relatively unusual cases stretch existing concepts to their limits. Our concepts weren’t designed for them, and we just don’t know what to say (and that’s okay). There are reasons both for and against saying that this is a lesbian and a gay man, respectively. In the first case, there’s female sexual attraction to a female-like body, at least on the outside, but the female-like body is artificially produced and not an endogenous phenotype. The body is actually male, no matter what it looks like. In the second, there’s male attraction to a male-like body on the outside, but again it isn’t endogenously produced and is a female body nonetheless.

For an objector to focus only on this sort of example is strange, because their own position would also classify as “lesbians” females who habitually lust after males with absolutely standard male bodies, as long as the latter had female gender identities. And it would even count males with standard male bodies themselves as lesbians—as long as they too had female gender identities. They would, for instance, presumably agree that Alex Drummond—a trans woman on Stonewall’s advisory board who has apparently had no surgery, taken no hormones, looks unambiguously male in terms of morphology, and even wears a full beard—is a “lesbian” because of an attraction to women. In a Buzzfeed interview Drummond says, “I identify as lesbian as I’m female and attracted to women … I’ve been in a long-term committed relationship for a long time now so I’m spoken for, but certainly I draw out the inner lesbian in women!” Yet this is surely to stretch the concept of lesbian to the breaking point. In old money, Drummond is heterosexual, and so, presumably, are the females attracted to her.

A third objection is an accusation: why are you “policing” sexualities? Can’t consenting adults just have sex with whomever they desire? My answer is: Of course they can (or at least, in an ideal world, should). This objection confuses accurate categorisation for the purposes of explanation with prohibition. I’m not setting myself up as the sex police. You can go to bed with whichever consenting adult you like. What I am saying is that if you consistently have enjoyable relations with someone of the opposite sex, you’re probably heterosexual/straight. That’s not to stop you doing what you like. It’s just to accurately describe what you’re doing. No judgement, positive or negative, is implied either way. (I’m gay myself.)

The long-term effects of LGBT organisations like Stonewall and GLAAD treating sexual orientation as based on gender identity have yet to be properly established, but at least two are emerging, neither good. First, it’s reported by some whistle-blower clinicians that significant numbers of trans-identifying children and teens are same-sex attracted. Taking a cue from the prominent public messaging of LGBT organisations, they seem to be interpreting their own patterns of sexual attraction as a sign that they must have a misaligned gender identity combined with a “straight” sexual orientation. So, for instance, same-sex attracted females are interpreting themselves to be straight boys or men. Identity exploration in children is not in itself harmful. However, it becomes a lot more serious when well-meaning parents and teachers uncritically go along with this narrative, seeking what may well turn out to be life-long medication on the minor’s behalf to alter his or her body to reflect a “real” identity.

Worse, also thanks to lobbying from LGBT organisations, some professional therapist bodies now characterise any questioning of this self-narrative as a prohibited form of “conversion therapy.” Hence, there are significantly reduced opportunities for a child or teen to hear alternative interpretations of their sexual desires. As these children grow up, some are coming to realise that they were just gay all along. A wave of “detransitioners” is emerging, many of whom are lesbian and gay, and many of whom now express regret about the life-altering drugs or surgery they were prescribed in the past.

A second problematic effect relates specifically to young lesbians: that is, to female-attracted females. Working out your homosexual orientation in a world in which heterosexuality is the norm can be difficult. Taking the difficulties on mentally while negotiating society’s expectations of you as a young female is tough. It’s fairly obvious that young females tend on average to be less assertive, more anxious, and keener to please than young males. Put these tendencies into a queer community in which young lesbians have sought refuge and comradeship, and in which there are also trans women self-declaring as fellow “lesbians,” and you will inevitably find lesbians—whether themselves trans-identified or not—pressured into sexual relations with members of the opposite sex, and in some cases succumbing.

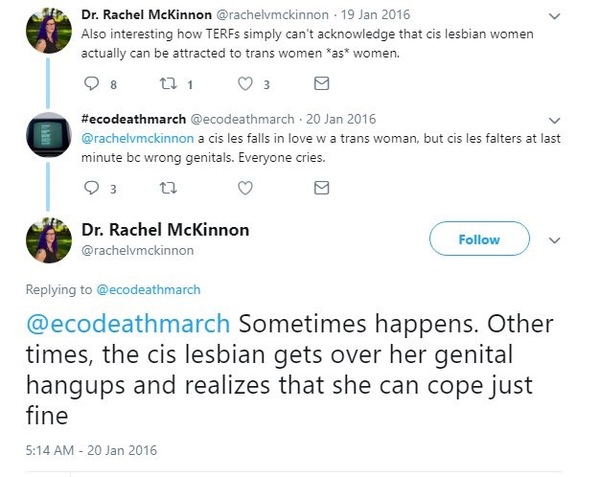

Recently, trans activism has given the world the fairly revolting image of the “cotton ceiling”: riffing on the idea of a glass ceiling for those women in the workplace unsuccessfully seeking promotion, but replacing glass with knickers to represent the “ceiling” that female-attracted trans women often cannot get “past.” Along similar lines, in 2016, a trans activist tweeted, in reference to sexual relations with trans women, that sometimes “the cis [i.e., non-trans] lesbian gets over her genital hang-ups and realises that she can cope just fine.”

In 2019, a University of Brighton conference, “Gayness in Queer Times,” asked, as part of its official call for papers: “How can gay space be made more trans-inclusive?” and then suggested “bedrooms” as a potential site of inclusion. Also in 2019, Oxford philosophy Professor Amia Srinivasan, writing in the London Review of Books, described “transphobia” as an “oppressive system that makes its way into the bedroom through the seemingly innocuous mechanism of ‘personal preference.’” Some legal theorists have even gone as far as to argue that the laws around “sex by deception” should be changed, so that, for instance, a trans man or trans woman initiating a sexual encounter with someone while actively falsely claiming to be of the same sex as them cannot be criminalised as fraud. Stonewall apparently agrees, arguing in 2015 that there should “be judicial clarity of ‘sex by deception’ cases to define the legal position on what constitutes sex by deception based on gender, and to ensure trans people’s privacy is protected.”

The implication of all this is that the main reason for a lesbian refusing to sleep with trans women, or a gay man with trans men, could only be bigotry and disgust for trans people. Yet this ignores a much more obvious explanation: it’s the sexual orientation, stupid. With such statements coming from what seem like authoritative liberal and left-leaning voices, we get a sense of what must be the moral pressure exerted at a more local level upon younger people ill-equipped to deal with it, and especially young lesbians. A former attendee of a trans youth group recalls that “one day, there were three MTFs [trans women, or male-to-female people] over 40 who were hitting on the teen FTMs, very explicitly. It was obviously making us uncomfortable, but almost no one ever said anything, only changed the topic or tried to engage them in a conversation away from us.”

If only those young FTMs—that is, trans men, or “Female To Male” people—had felt socially permitted, within queer culture, confidently to insist upon the fact of their same-sex attraction. Yet largely thanks to the LGBT organisations supposed to protect them, they weren’t. And many still aren’t.

Copyright © Kathleen Stock 2021, extracted from Material Girls: Why Reality Matters for Feminism. Published by Fleet, an imprint of Little, Brown Book Group Ltd.