Masochistic Nationalism—A Review

Post-colonial guilt in Britain and other formerly imperial Western powers can produce similar displays of self-flagellation and denial.

A review of Masochistic Nationalism: Multicultural Self-Hatred and the Infatuation with the Exotic by Göran Adamson. Routledge, 138 pages (March 2021).

In his 1945 essay, “Notes on Nationalism,” George Orwell contrasted “positive nationalism”—pride in one’s country—with the “negative” and “transferred” nationalisms displayed by supporters of the Soviet Union—the denigration of one’s country and the embrace of another. Actions are held to be good or bad, not on their merits, but according to who performed them. “Within the intelligentsia,” he wrote, “a derisive and mildly hostile attitude towards Britain is more or less compulsory, but it is an unfaked emotion in many cases.”

In his new book, Swedish academic Göran Adamson calls this combination of negative and transferred nationalisms “masochistic nationalism,” a term he then uses to analyse developments in modern Western Europe. Masochistic nationalism is defined as unjustifiable hostility to one’s own nation infused with a sense of pleasure and grandeur, combined with loyalty to another nation (or other nations) which are said to offer a more positive example of what nationalism ought to be. Adamson identifies some similarities between positive and masochistic nationalism but, as the title indicates, his focus is on the latter. He argues that many Westerners become fascinated by non-Western cultures because they assume this will provide them with an aura of self-critical virtue. Just as Orwell understood negative nationalism to mean that one’s own country must be wrong, Adamson understands masochistic nationalism to mean that “everything native must be criticised and everything exotic must be hailed.”

Adamson offers several examples in support of his case, but the divergent responses to two violent crimes committed in his native Sweden in 2015 are particularly instructive. First, a failed asylum seeker stabbed two native Swedes to death in an IKEA store in Västerås; then, a right-wing extremist murdered three immigrants in Trollhättan. In the latter case, the assailant and his victims became household names within days, and cities throughout the country held a minute’s silence to commemorate the dead. In the capital, Stockholm, the Social Democrats headed a candle-lit vigil “Against Racist Violence, and in Defence of Sweden as a Society characterised by Openness and Solidarity.” Hundreds of thousands answered a Facebook call to oppose “Racism and Xenophobia.” Any right-minded person would find this response laudable.

But in Västerås, all was quiet—there were no vigils, no minute’s silence, and no outpouring of grief on social media—and the victims (a mother and son) remained anonymous. Prime Minister Stefan Löfven rushed to Trollhättan but did not bother to visit Västerås. Adamson concludes that, notwithstanding their obvious similarities, one act is deemed a hate crime but the other is not. A meaningless, terrible act against non-Swedes produced nationwide soul-searching but an equally terrible act against two Swedes was quickly glossed over as if it were an embarrassment. And this is his deeply discomfiting point: “Sweden is influenced by an attitude whereby non-Swedes are systematically being favoured in relation to Swedes, that is, by masochistic nationalism.”

In 2009, an unemployed Muslim man refused to shake hands with a woman at the State Employment Agency and had his benefits terminated as a result. He filed suit and was awarded 60,000 kronor in damages. The head of the Swedish Bureau against Discrimination announced that he was relieved and thought the decision of the SEA was unacceptable in Sweden’s multi-religious society. Adamson points out that the man’s behaviour, despite its apparent basis in sincerely held cultural and religious beliefs, contravened the social rules of the agency and of Swedish society more generally. Importantly, the woman’s perspective and that of a society that proclaims gender equality were blithely ignored because she belonged to the white, Christian majority.

The simultaneous debasement of one’s own culture and the sanctification of those imported from poorer, non-white countries was graphically illustrated in 2002 by the former candidate for Prime Minister, Mona Sahlin. At a meeting of the Turkish youth organisation, she declared, “I think this is in a sense the reason why so many Swedes are so jealous of immigrant groups. You have a culture, an identity, a history, something that binds you together. And what do we have? We have midsummer night and ridiculous stuff like that.” Adamson notes that this was not an isolated absurdity but reflects decades of masochistic political discourse within Sweden’s political elite. At the same time, ideological blinkers help liberal Swedes avoid the uncomfortable realities of what might euphemistically be called the “troublesome” aspects of exotic cultures. It took Karen Jespersen, the former Minister of Integration in neighbouring Denmark, to point out that “it’s hard for cultural self-denial to be more monstrous and horrifying than this.”

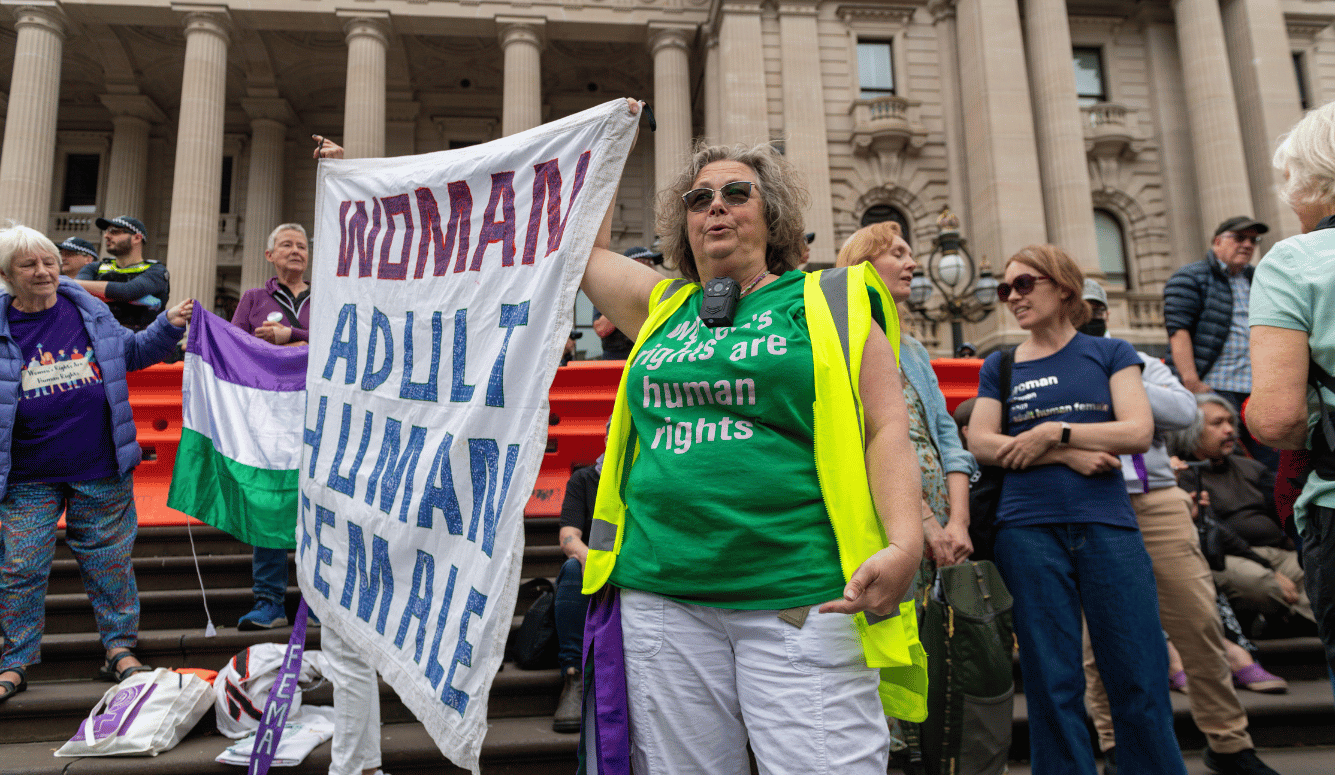

Post-colonial guilt in Britain and other formerly imperial Western powers can produce similar displays of self-flagellation and denial. For example, when the Jay Report examining child sexual exploitation in the Yorkshire town of Rotherham was published in 2014, it found that the perpetrators were almost entirely Muslim men. Denis McShane, who was the town’s MP at the time, frankly admitted in an interview, “I think there was a culture of not wanting to rock the multicultural community boat … Perhaps yes, as a true Guardian reader and liberal leftie, I suppose I didn’t want to raise that [issue] too hard.” White liberal guilt among the authorities allowed horrific acts perpetrated by men from former colonies against vulnerable white girls to pass unpunished—not just in Rotherham, but in several towns and cities in England. Had the perpetrators been white men and the victims Muslim girls, it is safe to assume that McShane and other “liberal lefties” would have demanded immediate action from police stations and town halls.

Adamson’s judgment is apposite here: masochistic nationalism has led to the replacement of the unfair treatment of minorities with unfair treatment of the majority. However, feelings of post-colonial guilt alone do not necessarily imply any sense of pleasure or grandeur, and the corrupting nature of the masochistic mindset also relies upon the promulgation of blatant falsehoods in defence of confected piety. For instance, a Swedish political party called the Feminist Initiative baldly stated that “Swedish men may well be the number one in the world in terms of harassment and violence against women”; a grotesque and easily disprovable lie given the evidence clearly indicating that men from an immigrant background are significantly over-represented in assaults against women in Sweden.

My only concern about the book is the author’s repeated attempts to draw similarities between positive and masochistic nationalisms. While Orwell was correct to draw attention to these, given Adamson’s focus and aims, there was no need to stress discourses around the former. Moreover, positive nationalism is not necessarily reactionary: it is a simple fact of life that individuals absorb the culture and modus vivendi of the society in which they are raised and that these naturally contribute to their identity. In Western Europe, in particular, the large numbers of people who have settled in the region in recent decades, often with markedly different values and mores, have produced much anxiety. This is surely understandable, since the multicultural emphasis on tolerance of difference and the relativist suspension of moral judgement has led governments to be tentative at best in their efforts to integrate these new citizens.

In Britain, for example, the 2014 British Social Attitudes Survey found that almost a fifth of respondents (18 percent) thought that British cultural life was “strongly undermined” by immigration, and a further 27 percent thought it was “undermined” (so, 45 percent held a negative view of immigration in regard to its cultural impact). By contrast, only six percent thought cultural life was “strongly enriched” by immigration and a further 29 percent thought it was “enriched” by immigration (so, 35 percent held a positive view of the cultural impact of immigration). This seems to illuminate an uncomfortable fact—that almost half the population thinks that British national identity has been compromised by mass immigration and multiculturalism. Legitimate concerns like these expressed by positive nationalists should not simply be condemned as expressions of unbridled xenophobia.

Back in 1973, the European Community drafted the Declaration on European Identity which pledged to uphold “the diversity of cultures within the framework of a common European civilization, the attachment to common values and principles, the increasing convergence of attitudes to life.” This was a benign form of positive nationalism that reflected reality. But almost half a century later, with rapid demographic change sweeping the continent, it is no longer possible to retain confidence in such an identity based on deep commonalities. The fracturing of such unifying values and principles has occurred because of the increasing prevalence of negative and masochistic nationalism, and it is to Göran Adamson’s credit that he makes this resoundingly clear.