Books

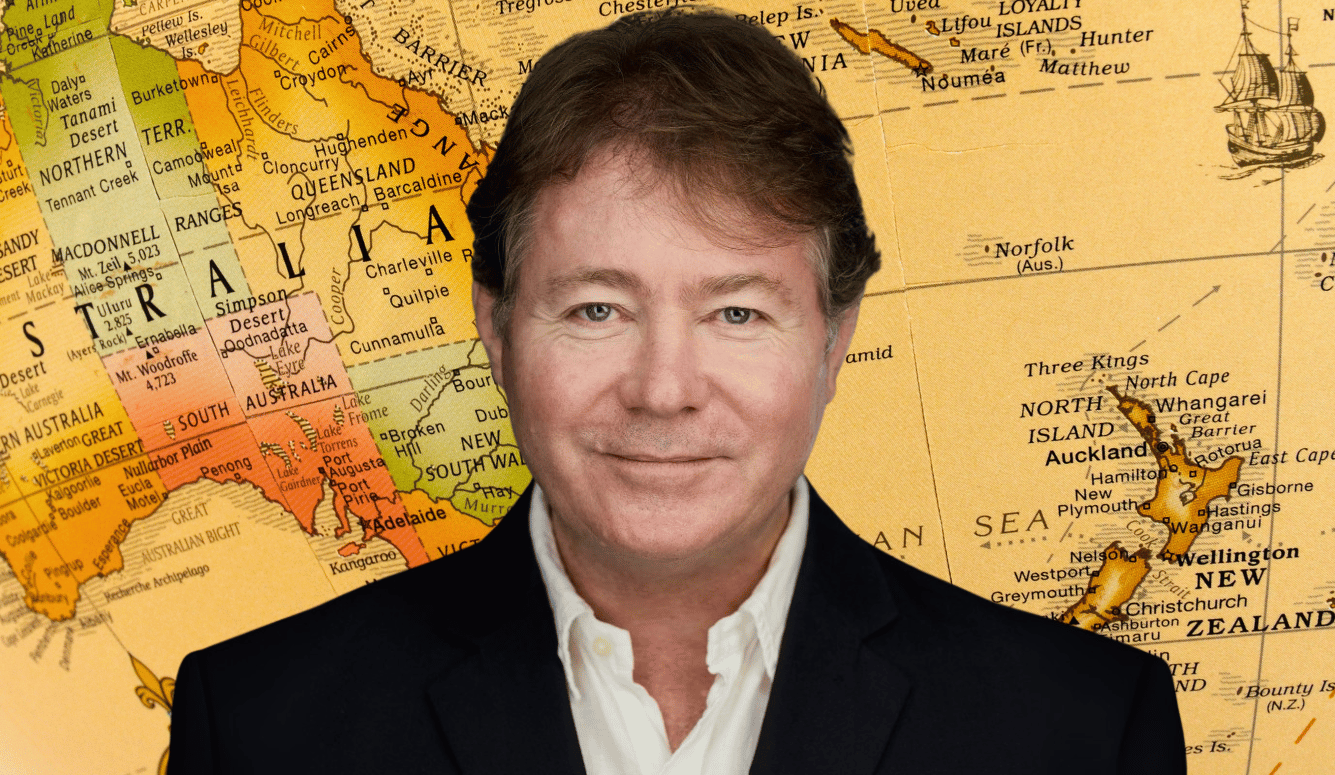

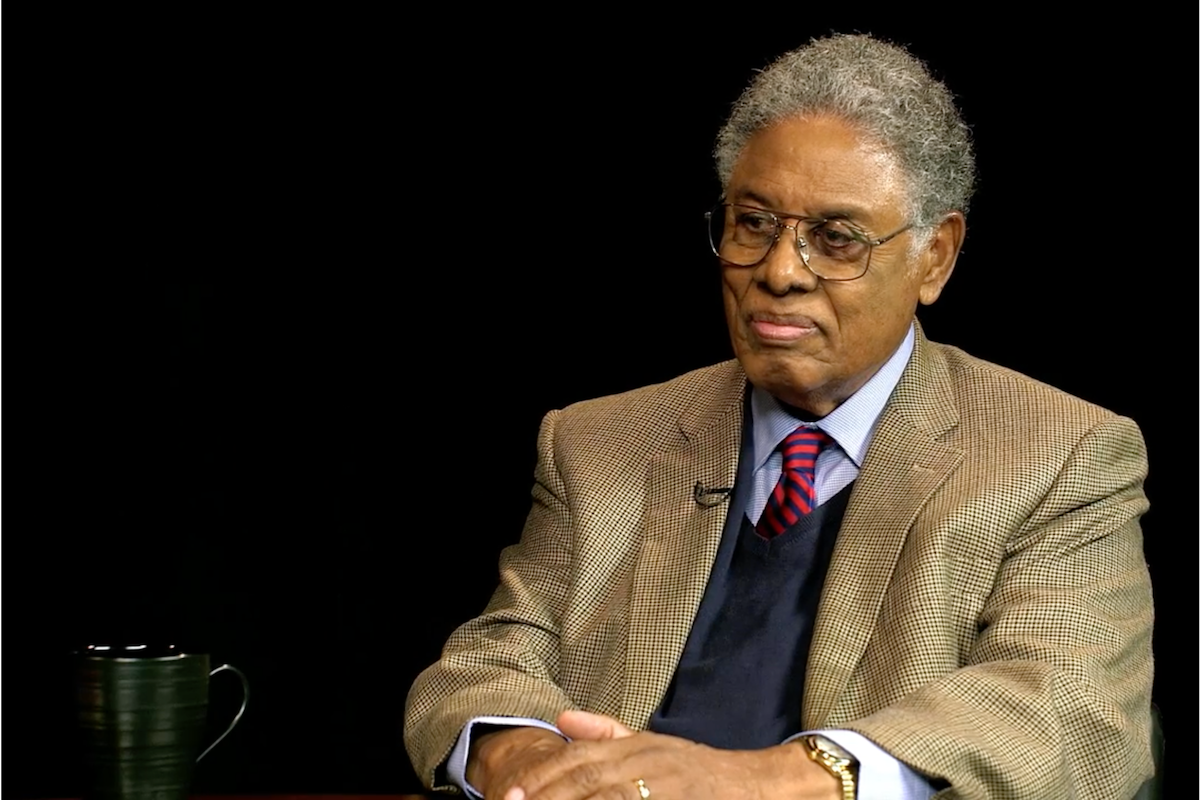

Thomas Sowell: Tragic Optimist

In his 2000 memoir A Personal Odyssey, Sowell recounts a parable that was read to him as a young boy and which he never forgot.

History is not destiny.

~Thomas Sowell, Race and Culture

Somewhere out of the mysterious interplay between nature and nurture, internal and external factors, cultures and structures, and bottom-up and top-down forces there emerge the individual and group outcomes that we care about and which ultimately make the difference between human flourishing and its absence. What distinguishes various political ideologies, in effect, is how the line of causation is drawn, or, more specifically, from which direction. What gets left unexamined in the rush for compelling narratives and ideological certainty, however, is the territory between different causes and how they combine to shape reality. Few have gone further to map that territory than the American economist, political philosopher, and public intellectual Thomas Sowell.

At 90 years of age, Sowell remains among the most prolific, influential, and penetrating minds of the past century. He understands the world in terms of trade-offs, incentives, constraints, systemic processes, feedback mechanisms, and human capital, an understanding developed by scrutinizing available data, considering human experience, and applying robust common sense. Sowell has written over 50 books according to his late friend Walter E. Williams, in which he has applied a humanist economic lens to issues as far-ranging as racial inequality, cultural history, intellectuals, Marxism, charter schools, late-talking children, and affirmative action policies around the world. His nationally syndicated column was published for decades in over 150 different newspapers, including National Review, the Wall Street Journal, and the New York Post. His ability to write with authority on a wide range of issues stems from a genuine curiosity about the world as it is and human beings as they are, not how things ought to be.

In his 2000 memoir A Personal Odyssey, Sowell recounts a parable that was read to him as a young boy and which he never forgot. “One story I found sad at the time, but remembered the rest of my life, was about a dog with a bone who saw his reflection in a stream and thought that the dog he saw had a bigger bone than he did. He opened his mouth to try to get the other dog’s bone—and of course lost his own when it dropped in the water. There would be many occasions in life to remember that story.”1 This set the tone for a life and career committed to closing the gap between image and reality. This is why Sowell’s contributions extend beyond partisan politics. His basic concern is with the dynamism, diversity, and development of living human beings, not inter-temporal sociological abstractions or racial archetypes that can be leveraged for political or moral power. Likewise, his basic orientation is that of a culturalist, with a belief in the effectiveness of evolved ideas, skills, attitudes, interests, and norms to change the course of human history, and the autonomy of individuals to adopt better cultural imperatives to improve their prospects and, crucially, those of their children.

“Cultures are not bumper stickers,” he once said during a lecture at the American Enterprise Institute. “They are living, changing ways of doing all the things that have to be done in life… Their legacies belong to all people and all people need to claim that legacy, not seal themselves off in a dead-end of tribalism or an emotional orgy of cultural vanity.” His work tells a story of human progress and cultural evolution amid the challenges of living in a multi-ethnic democracy and against the historical determinism and cultural relativism that prevent us from meeting our deepest potential as individuals and societies.

“With all that I went through,” Sowell says of his own rise to prominence, “it now seems in retrospect almost as if someone had decided that there should be a man with all the outward indications of disadvantage, who nevertheless had the key inner advantages needed to advance.”2

Sowell’s journey began on June 30th, 1930, in Gastonia, North Carolina, where he was born into poverty and segregation. Both of his biological parents died within the first few years of his life and Sowell was sent to live with his great-aunt and her adult daughters, not learning the truth of his origins until much later. There was no electricity or running water in the house and light and heat required the use of kerosene. Sowell was baffled to discover two running faucets in the kitchen of a white family his elder sister worked for, remarking at the time: “They must sure drink a lot of water around here.”3 He had almost no contact with white people and couldn’t understand why some of the characters in the comics he was reading had yellow hair.4 Of his schooling in the south, he wrote, “My only memories are of fights, being spanked by the teacher, having crushes on a couple of girls and the long walk to and from school.”5 With the attention and care of multiple adult family members, Sowell had already learned to read by the time he entered grade school and quickly excelled, managing all the course material for the semester in a couple of weeks. He speaks happily of his childhood. They were poor, but they had more.

On Mother’s Day 1939, when Sowell was eight years old, his family moved to Harlem as part of the Great Migration of southern blacks to northern cities. The experience was a major culture shock. Nobody in his family had made it beyond the seventh grade and the move was intended to expand his prospects. Sowell was encouraged to acculturate to city life and develop middle class norms, and discouraged from playing with the kids on his block. His family members introduced him to a neighborhood boy of West Indian heritage named Eddie Mapp, a good student who could play classical music on the piano. It was Mapp who brought the nine-year-old Sowell to his first public library. “Unknown to me at the time, it was a turning point in my life, for then I developed the habit of reading books.”6 As Sowell recounts in the recent documentary Common Sense in a Senseless World, narrated by the Wall Street Journal columnist Jason Riley (author of a forthcoming biography on Sowell), “Really, had I not encountered [Mapp], the entire rest of the story could not have been the way it was.” Cultural exposure was crucial to his development.

The Harlem schools were more rigorous than those in the south and adjusting to the higher academic standards was a difficult process. He began at the bottom of the class but refused to be held back a grade and even went to the principal to argue his case. Sowell consistently had trouble dealing with authority—or perhaps authority had trouble dealing with him. He resented the arbitrary rules and regulations of the school system and had physical altercations with his male teachers on more than one occasion. Nevertheless, he was already beginning to grasp the true diversity and complexity of American life. His junior high school was in a lower-middle-class white neighborhood comprised of over 40 different ethnic groups, “proud of its diversity and maybe a little too self-congratulatory.”7 It was here that he noticed one of his first racial disparities: “I do not recall ever losing a fight to a white kid my own size.”8