Books

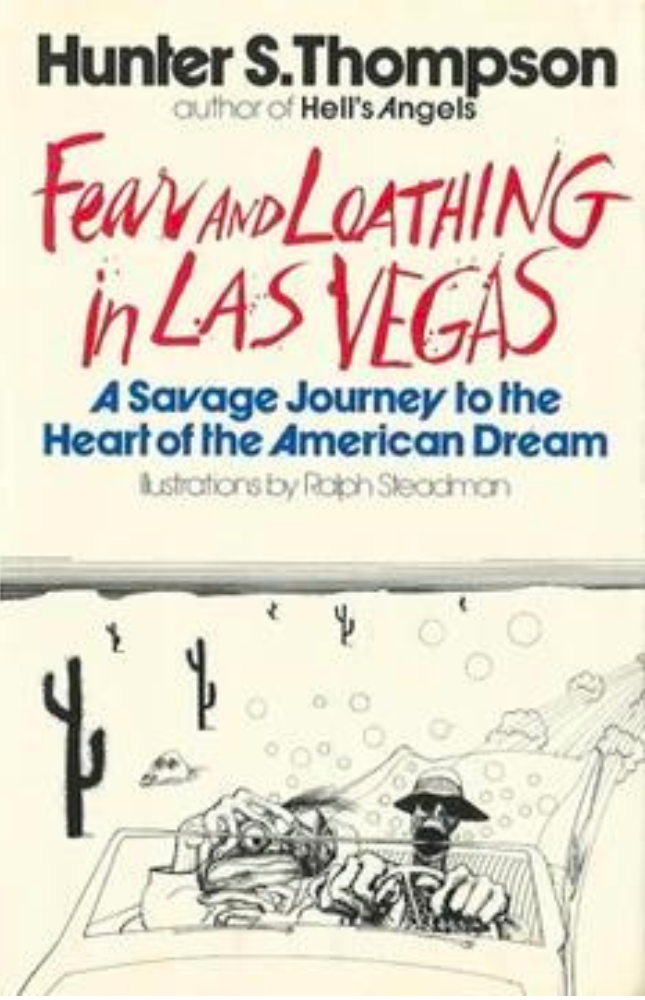

Fifty Years of Fear and Loathing

Finding out the truth about any aspect of Hunter Thompson’s life is frustrating given his propensity for self-mythologising.

On March 21st, 1971, Hunter S. Thompson and Oscar Zeta Acosta arrived in Las Vegas to cover the Mint 400 desert rally for Sports Illustrated. Asked to write a 500-word summary of the race to accompany a photograph, Thompson annoyed his editors when he turned in thousands of words about his escapades in the city of sin, with barely a mention of the race itself. This bizarre piece of writing ultimately became Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, one of the most important but misunderstood novels of the 20th century.

In 1971, Hunter S. Thompson was at the peak of his literary powers but not yet a household name. His first book, Hell’s Angels, had been published to widespread acclaim just five years earlier, and in 1970, he had stumbled upon a great literary breakthrough with an essay entitled “The Kentucky Derby Is Decadent and Depraved,” a piece of writing so unique that it created a new literary genre that came to be known as “Gonzo journalism.” As the star writer for Rolling Stone, Thompson then embarked upon a more serious piece of journalism: a 20,000-word essay on the murder of Ruben Salazar, a Chicano rights activist murdered by the LAPD.

In Los Angeles, Thompson and Acosta, a prominent Chicano lawyer, worked together to report on the case, but they found it was impossible to communicate openly. Acosta’s militant friends were unhappy with the white journalist in their midst and both men feared they were under surveillance by the authorities. So when Thompson was offered what seemed to be a straightforward sports-writing gig in Las Vegas, the two men seized the opportunity to escape. They hired a large convertible and sped off through the desert, which is where Thompson’s story begins:

We were somewhere around Barstow on the edge of the desert when the drugs began to take hold. I remember saying something like “I feel a bit lightheaded; maybe you should drive…” And suddenly there was a terrible roar all around us and the sky was full of what looked like huge bats, all swooping and screeching and diving around the car, which was going about a hundred miles an hour with the top down to Las Vegas.

From the outset, Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas is an outrageous and darkly amusing tale of two crazed men turned loose in the world’s capital of decadence. Raoul Duke and Doctor Gonzo, clearly based upon Thompson and Acosta, are carrying a veritable pharmacopoeia in the trunk of their rented car, and throughout the novel they abuse a litany of substances as they stumble through casinos, bars, and hotels terrorising staff and patrons alike. Though Duke and Gonzo are, like the real Thompson and Acosta, tasked with covering the Mint 400, their assignment is quickly lost in the carnage. Near the end of the book, Duke admits he “didn’t even know who’d won the race.”

If you are unfamiliar with Thompson’s work, you may wonder why it matters that their efforts to complete a minor assignment ended in failure. Authors like Ernest Hemingway had mined their journalistic experience for material to incorporate into their fiction, so it is hardly unusual that Thompson would find inspiration for a novel whilst covering the Mint 400. But his approach with this book went beyond mere inspiration. Throughout Fear and Loathing, reality and imagination are blurred to the extent that no one really has much idea of what really happened on their trip.

Even before it was released, Fear and Loathing proved to be a headache for its publishers, bookstores, and newspapers, all of whom demanded to know whether it was a work of fiction or a piece of creative journalism. Thompson was adamant that such distinctions were outdated, calling fiction and non-fiction “19th-century terms.” For years he had been attempting to fuse fact and fiction in a new form that he called “personal journalism,” inspired by Orwell’s Down and Out in Paris and London and Kerouac’s On the Road, with an obnoxious protagonist cribbed from The Ginger Man, an approach to thematic exposition adapted from Hemingway, and the concise, era-defining prose of Thompson’s favourite novel, The Great Gatsby.

“The Vegas book,” as he often referred to it, was written like a novel but detailed apparently real events. In a sense, it was like New Journalism, except that real places and people and events were supplemented with fictional ones. This was an approach Thompson adopted throughout his career as a writer, making up quotes and statistics as a young reporter and including flights of fancy in politic coverage, such as the transformation of Richard Nixon into a salivating werewolf. Sometimes it was obvious what he was doing; other times it was hard to tell.

The idea of deliberately confusing his readers with a blend of reality and imagination came about in the late ’60s as a response to what Thompson perceived as state-sanctioned propaganda and the collusion between public relations managers and the media. He pitched ideas for books that would chronicle real events but with fabricated ones inserted surreptitiously, pushing his readers to do more than simply accept what they were being told. It was for precisely this purpose that he invented the character of Raoul Duke. Although Duke’s name first appeared in Hell’s Angels, with several references littering Thompson’s journalism and notes in the following years, he was only successfully deployed with Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas. However, Thompson had known for several years that Duke was the key to bridging the gap between reporting and fictionalising events.

Thompson most likely came up with the name Raoul Duke in 1965 while he was preparing to write Hell’s Angels. Raoul “Duke” Duquette was a Canadian businessman whose name was often in the papers that year. Given Thompson’s voluminous research for his book, it is likely that he stumbled upon this name and borrowed it, as he did with so many names and words and phrases that he liked. For years, he struggled with a follow-up book but his ideas increasingly came to rely upon Duke as the central character and “the Death of the American Dream” as its theme. With the assassinations of Martin Luther King and Bobby Kennedy, followed by the horrors of the Democratic Convention in Chicago, Thompson felt in 1968 that he had witnessed the end of an era that had offered hope and freedom.

He knew that somehow Raoul Duke was a means to explore this theme, but even as he set off across the desert, he had no idea that he was living out the story of his next book and that he was becoming Duke. Yet that is largely what happened. In Vegas, Thompson and Acosta made no real effort to cover the race and instead embarked upon several days of drinking. At some point, though, it became clear that they were doing more than just getting hammered. Thompson began scrawling notes about the things he saw—and, of course, things he didn’t see. He let his imagination run wild and minor incidents were blown all out of proportion. When he left Vegas, he continued writing. Layer upon layer of absurdist fantasy was imposed on their drunken misadventures.

For the rest of his life, Thompson played coy with interviewers and fans who asked about the extent to which the book was based on real events. His answers varied depending on his mood and, alas, it is impossible to say for sure how much was real and how much was imagined. To Thompson, though, it never really mattered. He believed journalism was art and that art should be experienced on its own terms, without further explanation. Still, the question of what really happened in Vegas remains tantalising, not least because Thompson insisted upon playing cat-and-mouse with the truth, teasing readers and deliberately blending reality and hallucinatory imagination on both the pages of the book and in interviews about it.

Finding out the truth about any aspect of Hunter Thompson’s life is frustrating given his propensity for self-mythologising. From a young age, he learned to adopt personae and tell stories about his life that were hard to believe. As a young journalist, he began inserting himself into his stories as an intrepid reporter, fearless but often comically incompetent. His penchant for exaggeration and fabrication means that even now, after a number of biographies, it is hard to pin down the truth about his life and work. Like Bob Dylan, he countered attempts to reveal the truth with further obfuscation.

Thompson describes Duke as wearing the usual Hunter Thompson attire (aviators, cigarette holder, sneakers) and also mentions his “crippled, loping walk”—a gait that made Thompson instantly recognisable, even at a distance. At the end of part one, Duke receives a telegram addressed to “Hunter S. Thompson c/o Raoul Duke,” which provokes a comically confusing conversation with a hotel clerk. In part two, a casino bouncer shows Duke a photograph of the real Thompson and Acosta in Vegas. Denying it is him, Duke says, “That’s a guy named Thompson. He works for Rolling Stone… a really vicious, crazy kind of person.”

This photo was prominently displayed on the back cover of the first edition of the book, with both men identified. The caption says, “Oscar Zeta Acosta… insists on being identified as Dr. Gonzo.” This was added in part to placate Acosta, who had threatened to derail the book’s publication after falling out with Thompson. In his mind, Doctor Gonzo was his intellectual property and he had been given next to no credit by a man he considered a close friend. Thompson contended that he had obscured Acosta’s true identity in order to protect him. He was, after all, a lawyer and facing various legal problems of his own.

But the photo was also included as a both a form of playful metatextual confusion and as another ego-trip for Thompson, who had always gone to lengths to present himself as an oddball anti-hero. He wanted his readers to believe that he had run amok in Las Vegas in an epic drug frenzy. He even confessed as much to Jim Silberman, his editor at Random House:

All I ask is that you keep your opinions on my drug-diet for that weekend to yourself… the piece has already fooled the editors of Rolling Stone. They’re absolutely convinced, on the basis of what they’ve read, that I spent my expense money on drugs and went out to Las Vegas for a ranking freakout.

In this letter, he made the startling confession that Fear and Loathing had not merely exaggerated the debauchery that took place in Vegas, but that there had in fact been no drugs at all. Could this really be true? Was the most notorious drug book of its era really inspired by a drug-free journey?

Before we can answer that, it is important to note the chronology of events on which the book was based. Whilst the book portrays the two men tearing apart hotels and casinos over a period of several days, there were in fact two distinct trips. First, they went to cover the Mint 400 on Mach 21st–23rd, then they returned for the National District Attorneys’ Conference on Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs on April 25th–29th. Thompson simply rolled the two events together into a single narrative. The evidence suggests that, during the first trip, Thompson and Acosta drank heavily and perhaps smoked a little pot, but certainly did no serious drug-taking. The famed pharmacopeia in the trunk of their convertible was fictitious:

The trunk of the car looked like a mobile police narcotics lab. We had two bags of grass, seventy-five pellets of mescaline, five sheets of high-powered blotter acid, a salt shaker half full of cocaine, and a whole galaxy of multi-colored uppers, downers, screamers, laughers… and also a quart of tequila, a quart of rum, a case of Budweiser, a pint of raw ether and two dozen amyls.

As tempting as it is to believe that this existed, it was a product of Thompson’s prodigious imagination. He was, however, keen to keep his readers in the dark, hence his letter to Silberman and the inclusion of his photo on the back cover. Since childhood, he had been obsessed with appearing as an outlaw, yet real outlaws never explicitly said that’s what they were. They merely hinted at it.

Of course, Thompson’s “drug-diet” did consist of various illegal substances, which made his descriptions of their effects rather convincing, but not only did he remain mostly drug-free in Vegas, he also wrote the novel with little more than beer and tobacco in his system. Back home in Colorado, he polished his story carefully through many drafts. The result was a far more intelligent and coherent work than almost anything else he published.

It was only during the second of the two trips that they began to consume drugs, but even then their indulgence was mild when compared with Duke and Gonzo’s extravagant excesses. They had marijuana, a few pills, and possibly some mescaline, but nothing else. His descriptions of LSD came from experiments several years earlier, the parts about adrenochrome were entirely fabricated, and—surprisingly—Thompson had not yet tried cocaine by 1971.

Whether the drugs were real or not, Fear and Loathing is very much a drug book. As a piece of writing intended in part to act as a reflection upon the ’60s’ hippie ethos, it depicts hallucinogens like LSD and mescaline vividly, though exaggerated for comic effect. Importantly, however, Thompson was keen to criticise the naïve hippie mysticism of Timothy Leary and others who recommended powerful drugs as a form of spiritual liberation. For Thompson, drugs were messy but fun; a necessary release from the daily grind. This book was among the first to reflect that side of their use.

Although he was no hippie, Thompson enjoyed their drugs and music and had lived on the fringe of the hippie sub-culture in San Francisco during the mid-’60s. He admired their values even if he recognised a naivety that ultimately doomed their movement. He had briefly shared in their optimism, but for him this had died amid the political violence and clouds of tear-gas in 1968. It is no coincidence, then, that when Duke and Gonzo search for the American Dream in Las Vegas, they are led to the site of a nightclub that had burned down during that tumultuous year.

In the novel, this discovery occurs following a conversation with two waitresses at a taco restaurant, and surprisingly this was transcribed from a genuine recording that Thompson and Acosta had made in Vegas. More interestingly, it was Acosta that led their search for the American Dream whilst Thompson was preoccupied with a more tangible quest for drugs. He took charge of their interviews and actively pushed them in search of the book’s theme, insisting upon finding a physical location for the American Dream.

The book that was subtitled “A Savage Journey to the Heart of the American Dream” had confusingly meandered through the desert and into Las Vegas via a mess of flashbacks, flights of fancy, and even some philosophical tracts, but it ultimately arrived at this destination. Yet the book is still best known as an epitaph for the counterculture. In the novel’s most famous passage, Thompson mimics the rhythms and themes of the final pages of The Great Gatsby to produce one of the most poignant descriptions of that era:

And that, I think, was the handle—that sense of inevitable victory over the forces of Old and Evil. Not in any mean or military sense; we didn’t need that. Our energy would simply prevail. There was no point in fighting—on our side or theirs. We had all the momentum; we were riding the crest of a high and beautiful wave… So now, less than five years later, you can go up on a steep hill in Las Vegas and look West, and with the right kind of eyes you can almost see the high-water mark—that place where the wave finally broke and rolled back.

It is an odd section to include in a story ostensibly about two men attempting to cover a race in the desert, but then that race was always just a MacGuffin—an excuse for Thompson and Acosta to get out of Los Angeles and to explore the American Dream. The book itself was a collage of sorts—more a chaotic collection of connected vignettes than a coherent plot. It began with a failed sports-writing assignment and continued when Thompson and Acosta returned for the conference.

Much of the story had already been drafted when a Rolling Stone staffer suggested Thompson attend the DA convention. Thompson latched onto the idea, deciding it would be perfect for two degenerates to infiltrate the event as an exposé of institutional incompetence. They planned to walk among the supposed experts whilst tripping on mescaline, listening to them pontificate about drugs oblivious to the invaders in their midst. Layers of fiction were added by Thompson, blending genuine quotes from the conference with imagined ones, and an invented conversation in which Duke and Gonzo convince a district attorney from Georgia that the police in California have taken to decapitating Satan-worshipping drug addicts in order to stop their crime sprees.

This was the same approach he would later take to reporting on politics. Whilst most of the media took candidates’ statements at face value, essentially amplifying lies, Thompson chose to include deliberately absurd stories and treat them as if they were true. In his own mind, any half-intelligent reader would be able to delineate fact from fiction. In Fear and Loathing, Thompson recounts genuine quotes from reading materials at the convention, but then confects his own, claiming that a user of marijuana can be identified because “his knuckles will be white from inner tension and his pants will be crusted with semen from constantly jacking off when he can’t find a rape victim.”

Thompson used black comedy and an anarchic blend of fact and fiction to make his critiques of American culture. Chief among these was the idea that Las Vegas represented the very worst of American life. Duke and Gonzo are deranged by ether, acid, and adrenochrome and yet they remain indistinguishable from the usual tourists and their hallucinations are scarcely distinguishable from the tasteless, indulgent décor of any Vegas casino or hotel. Whilst the book appears to celebrate meaningless excess, it is in fact a damning critique of a culture of greed and hypocrisy.

Thompson’s conflation of reality and fiction was carried out of the narrative and into the real world when his story was first published in two instalments in Rolling Stone. Here, it was credited to Raoul Duke rather than Hunter S. Thompson, but eight months later the book was published under Thompson’s own name. It was an instant hit. Even though reviewers could hardly tell where Thompson ended and Duke began, they seemed to understand what he was trying to do. His bizarre approach to satire was widely recognised as the most inventive and brilliant American novel (as most chose to label it) since Naked Lunch.

What began as an assignment for a 500-word caption for a sports magazine in March 1971 ended up as a genre-bending, era-defining book in July 1972. The Mint 400 barely featured, but that hardly mattered. A failed attempt at sports writing had resulted in a book about a failed attempt at sports writing that in fact charted the end of the hippie dream and the death of the American Dream as Thompson understood it. It was an accidental masterpiece; the definitive study of the counterculture era, whose “wave passage” was as beautiful and concise a description of that phenomenon as has ever been written. Indeed, it was this elegiac lament, this lyrical prose, fused with a hysterical, dark, inventive, madcap story that made Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas an instant classic. Even now, 50 years later, it is celebrated for its puerile surface details—the drugs, the madness, the abhorrent behaviour—but lying just beneath that is one of the most beautiful, brilliant, and complex pieces of writing in American literature.