Books

Before 'Groundhog Day': The Time-Loop Novel that Started It All

On March 4th, the Ringer, a website that covers pop culture, featured an article entitled “We’re in a Time Loop of Time-Loop Movies.” Similar articles have appeared in many other pop-culture venues of late. Suddenly, time-loop stories seem to be everywhere. This month Hulu began streaming director Joe Carnahan’s new sci-fi action film Boss Level, the tale of a soldier in the near future who wakes up every morning only to relive the day of his death. Carnahan has described the film as “Groundhog Day as an action movie.” A few weeks before the release of Boss Level, Amazon Prime released director Ian Samuels’s film The Map of Tiny Perfect Things, which could be described as Groundhog Day as a teenage romance. Last July, Hulu released director Max Barbakow’s film Palm Springs, a time-loop story starring Andy Samberg, Cristin Milioti, and J.K. Simmons. The film is both a romance and an action film.

It’s no surprise that time-loop stories seem suddenly relevant to many pop-culture consumers. Because of the coronavirus pandemic and the various quarantines and lockdowns it engendered, the year 2020 had a lot of people feeling as though they were stuck in a time-loop. If you were a worker whose job could be performed remotely from your home, then nearly every day of 2020 was fairly similar. You probably didn’t leave the house, you didn’t have to put on work clothes and so probably wore the same two or three items over and over again, you couldn’t go out to eat at a restaurant so you probably ate a lot of the same meals (frozen pizzas, cereal, canned soups) over and over again, and you interacted personally with only a small handful of people, most of them relatives. But what’s curious about the current time-loop phenomenon is that all of the recent films and TV series employing that trope were in the works long before anyone had heard of COVID-19.

The last decade or so has given us dozens of variations on the Groundhog Day theme. Critics described director Christopher Landon’s 2017 horror film Happy Death Day, about a sorority girl forced to relive the day of her murder over and over again, as “Groundhog Day meets Scream.” It was successful enough to inspire a 2019 sequel, Happy Death Day 2U, and an as-yet-untitled threequel, which is still in the works. Netflix’s 2019 limited TV series Russian Doll starred Natasha Lyonne as a computer-game developer who finds herself stuck in a time-loop that forces her to relive the same day over and over again. A second season is in the works. Both Rian Johnson’s 2012 film Looper (as the title suggests) and Christopher Nolan’s 2020 film Tenet play with the idea of time-reversibility and the possibility of revisiting certain events in the past over and over again. The 2014 Tom Cruise vehicle Edge of Tomorrow, directed by Doug Liman, is about a public relations specialist for the military who finds himself forced to relive the same events over and over again. Cruise’s character, Major William Cage, is not confined to the events of a single day. Time doesn’t reset for Cage until he dies, at which point he always returns to the same starting point. The 2017 film Before I Fall, directed by Ry Russo-Young, tells the story of a teenage girl trapped endlessly in the same day. Amazon Prime’s 2018 limited series Forever starred Maya Rudolph and Fred Armisen as a married couple who die and find themselves in an afterlife in which every day at first appears to be largely a repeat of the previous days. The 2020 Amazon Prime series Upload, created by Greg Daniels, the man behind the American version of The Office, also treats the afterlife somewhat like a time-loop that must be escaped. Amazon Prime seems to specialize in time-loop-adjacent fictions. The Amazon Prime series Tales of the Loop (as the title suggests) plays with a variety of temporal conundrums (for instance, what would you do if you could stop time for everyone but yourself and your lover, essentially living in the same day forever?). The 2020 Netflix limited series The Haunting of Bly Manor condemns some of its characters to repeat the past over and over again. A Wikipedia page entitled “List of Films Featuring Time Loops” contains 49 entries to date.

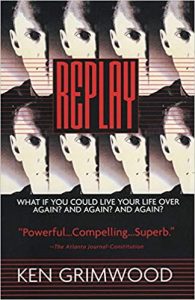

One of the odd things about the time-loop genre is that just about everyone credits the 1993 Harold Ramis film Groundhog Day as its progenitor. This is curious because, in its original release, the film was only modestly successful and didn’t inspire any immediate successors. It didn’t make the list of the 10 highest grossing films of 1993, finishing well behind such forgettable fare as Cliffhanger and The Pelican Brief (as well as such cultural landmarks as Jurassic Park, Schindler’s List, Mrs. Doubtfire, The Fugitive, and Sleepless in Seattle). It also received not a single Academy Award nomination. But what is really frustrating to many fans of fantasy and science-fiction literature is that, in January of 1987, a full six years prior to the theatrical release of Groundhog Day, Arbor House, a science-fiction imprint, published a novel called Replay by Ken Grimwood that essentially laid down the ground rules for all of the time-loop stories, including Groundhog Day, that would follow over the next three decades and more. And Replay was not an obscure or neglected book. It won the 1988 World Fantasy Award for best novel, beating out tough competitors including Stephen King’s Misery, Clive Barker’s Weaveworld, and John Crowley’s Ægypt.

The 1980s were a decade particularly rich in fine fantasy novels. Hundreds of highly regarded titles were published during that 10-year span including Gene Wolfe’s The Shadow of the Torturer, Peter Straub’s Shadowland, John Crowley’s Little, Big, D.M. Thomas’s The White Hotel, George R.R. Martin’s Fevre Dream and The Armageddon Rag, John M. Ford’s The Dragon Waiting, Stephen King’s Pet Sematary, Dan Simmons’s Song of Kali, Anne Rice’s The Vampire Lestat, Patrick Süskind’s Perfume, and many others. Only 11 novels were awarded World Fantasy Awards in that decade (in 1985 two books tied for the honor) and Replay was one of them. The book has been included on a number of guides to the best fantasy and/or science-fiction novels of all time. In 2015, the Easton Press brought out a specialty edition of Replay bound in leather and embossed with gold accents. It quickly sold out and copies of that edition can’t be found online for less than $145.

Plenty of time-travel stories existed prior to the publication of Replay in 1987. But time-loop stories—tales in which individuals are condemned to repeat the same day or week or year over and over again—were almost unheard of prior to the arrival of Replay. In its entry for Replay, Wikipedia lists only one earlier example of time-loop fiction, a story by Richard Lupoff called 12:01 P.M., which appeared in the December 1973 issue of the Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction. It tells the story of a New York business executive forced to relive the same hour over and over again. It was made into an Academy-Award-nominated short film in 1991 and a TV movie in 1993, the same year as Groundhog Day. Lupoff and Jonathan Heap, the director of the short film, believed that Groundhog Day violated their copyright and considered suing Columbia Pictures for damages. After six months of conferring with lawyers, Lupoff and Heap apparently decided that a protracted battle with a deep-pocketed corporate entity wasn’t worth the effort, and Columbia was allowed to get away with the rip-off (Loop-off?). Besides, Lupoff’s story wasn’t the first to feature a time-loop. In 1892, William Dean Howells published a story called Christmas Every Day, about a girl who spends an entire year reliving Christmas. What’s more, Lupoff’s story is little more than a nightmare about a man trapped in an endless time loop. Even if he kills himself, the protagonist starts all over again at 12:01 P.M. of the same day. He has no time to implement the self-improvement strategies adopted by Bill Murray in Groundhog Day or Cristin Milioti in Palm Springs or Tom Cruise in Edge of Tomorrow. But the protagonist of Replay does find time to completely remake himself during the course of his endless time loop. And so it’s Grimwood’s novel, rather than Lupoff’s short story or Ramis’s film, that would seem to be the progenitor of the contemporary time-loop genre.

Replay is the story of Jeff Winston, a 43-year-old news producer at a New York City radio station, who drops dead of a massive heart attack in the first few pages of the novel, at precisely 1.06pm, October 18th, 1988. But instead of ceasing to exist, he wakes up back in his old dorm room at Emory University in Atlanta, Georgia. The time is May of 1963. Although he finds himself back in his 17-year-old body, he still possesses all his memories of his previous life. He knows, for instance, that President Kennedy will be assassinated later in the year. He also knows who will win the Kentucky Derby that year and who will win the World Series. He uses his knowledge of the future to quickly amass a fortune by betting on sporting events whose outcome he already knows and by investing in companies that he knows will soon become darlings of the stock market. He founds a company of his own, Future, Inc., which becomes hugely profitable. He makes an attempt to prevent the Kennedy assassination. And when his effort fails, he pretty much gives up on the idea of altering major world events and spends the next few years increasing his fortune and pursuing love in all the wrong places. At one point he goes to Boca Raton, Florida, and tries to woo his former wife, Linda, but this time around she wants nothing to do with him (probably because he is now a cocky rich guy, and she can sense it). Eventually he marries a woman named Diane and, though their marriage is a troubled one, they produce a daughter, Gretchen, who is the love of Jeff’s life. He takes great care of himself physically. He exercises regularly to keep his heart strong this time around. He is rich and can afford the finest medical care. And yet, at 1.06pm, on October 18th, 1988, he suffers a massive heart attack, dies, and once again finds himself back at Emory University in 1963.

This cycle will repeat itself over and over again throughout the novel. Every time he arrives back in the past, Jeff retains all his memories of his previous lives. He tries to use this information in order to avoid heartbreak and to make himself a better person. Eventually he will find evidence that there are other “replayers” out there. He forms a strong bond with one of them, a woman named Pamela Phillips, and they spend several relatively happy lifetimes together. Alas, a snake lies hidden in their Garden of Eden, something called “the skew.” Every time Jeff dies, he travels a bit less far into the past. On his second return, he arrives not in May of 1963 but several months later in the year. On subsequent returns he skips all of 1963, arriving in 1966, and then 1969. The same thing is happening to Pamela, but her skew is not in perfect sync with Jeff’s. Thus it becomes harder for them to find one another in each new iteration of the past. In his later replays, Jeff returns to a past in which he is already a married man. And thus he must extricate himself from his marriage with Linda in order to be with Pamela. Complications continue to compound. Grimwood does an excellent job of ratcheting up the stakes and the suspense. Wisely, he never fully explains the origins of the time loop in which Jeff and Pamela are stuck. He focuses instead on what two well-meaning, highly intelligent and creative people might do given such bizarre circumstances. Some of their replays are more successful than others.

Replay is not just a fantasy novel. It is also a romance and an adventure and a mystery. And it is a pop-culture artifact that celebrates a lot of other pop-culture artifacts—Spielberg movies, Hitchcock movies, TV shows like Laugh-In and The Name of the Game, popular music, popular books. Grimwood was born in 1944. He grew up in Florida and Alabama. He was steeped in the pop culture of mid-20th-century America. He was also a Los Angeles radio news producer, and he had a sure knowledge of all the big news events of the 1960s, ’70s, and ’80s. His vast knowledge of world events and the pop culture of the era makes Replay an enjoyable blast from the past. If it had been written by Michael Crichton it would probably have spawned an entire entertainment-industry franchise—at least one follow-up novel, several films, perhaps a TV series. I’m a big Crichton fan, but I’m glad he didn’t write Replay. If he had, the book would probably have focused more on explaining various theories of time travel than on developing real flesh-and-blood people and the various ways they choose to navigate the difficulties life throws at them. Crichton was born two years before Grimwood but seems to have come from a different era entirely. His work evinces no nostalgia for the pop culture of 1950s, 1960s, or 1970s. It either looks ahead to the future (as in Prey) or behind to a faraway past (such as in The Great Train Robbery and Dragon’s Teeth) or it looks in both directions at once (as in Westworld and Jurassic Park and Timeline).

If Replay had been written by Stephen King, it would have been made into a major motion picture no later than 1990 and would probably now be undergoing adaptation as a quality TV series for HBO, Amazon Prime, or Netflix, something along the lines of Under the Dome, 11-22-63, and Castle Rock. But, as much as I admire King, I’m glad he didn’t write Replay either. If he had, the book would probably have built to some huge apocalyptic finale. Instead, Grimwood gives us a quiet, hopeful but not fully resolved finale which focuses on the ordinary human aspects of Jeff Winston’s life and not on the apocalyptic possibilities of the extraordinary time loop in which he finds himself trapped.

Replay is neither a lost classic nor a bona fide pop-cultural landmark. Most pop fiction fans have probably never heard of the book or the author. But it remains in print, it seems to be attracting new fans all the time, and Hollywood has been sniffing around the property for years and will probably bring it to the big or the small screen at some point. Ken Grimwood was working on a sequel when he died at the age of 59 (Replay’s epilogue hints at a sequel that covers the years 1988–2017). Although I lament his death, I’m glad he never produced a sequel. Replay is damn near-perfect as it is.