Memoir

To Skate—Perchance to Soar

Skateboarding is simple and complex, pointless and transformational.

Nairobi, January 2021. Saturday morning. I whizz joyfully around the multi-coloured skatepark. Beneath my feet, the board responds with twists and turns. I apply pressure with my toes and heels. I pop its tail and jump. It rises into the air, lifting me with it. My confidence grows. Now I decide to drop in from the edge of the kidney shaped pool. My heart races. I fly into its deep end and carve around the bowl’s steep edges. But I am coming back over the hip when, abruptly and unexpectedly, the skateboard slips away from me. My fast-moving body obeys its own trajectory. I fly up, then down, before crash landing—arms splayed, chest first—on the hard concrete. The impact knocks the breath out of my lungs. I roll onto my back, gasping. Faces appear above me, silhouettes against the blinding equatorial sun. They keep saying sorry. What for, I wonder? It’s not their fault.

It might seem odd, given that I am in a skatepark and far from the written word, but gathering my breath, I find myself thinking about Antoine de Saint-Exupéry and Wind, Sand, and Stars, a work I recently discovered by chance. I remember that, in the foreword to the book, which describes his life as a commercial pilot opening up mail routes across the world, the author asserts that self-discovery “comes when man measures himself against an obstacle. To attain it, he needs an implement.” The words “obstacle” and “implement” bounce painfully around my mind. Published just before the Second World War, Wind, Sand, and Stars is more than mere reflection on the challenges and romance of early flying: it is an existential treatise on identity in post-industrial society. A society, which, in Saint-Exupéry’s view, reduced most humans to exhausted, dormant lumps of “wet earth,” stripping them of emotional life and creative energy.

Saint-Ex, as his friends called him, found his implement to be an aircraft. Flying across the Saharan desert or the Andean mountains, often by night, connected him to the universe and its deeper questions. But writing at a time of immense change and upheaval, he was also aware that commercial flight and the technological advances it heralded were happening so fast that mankind was struggling to keep up: “Everything has changed so rapidly around us: human relationships, working conditions, social customs. Our very psychology has been rocked on its most intimate foundations… We are all young barbarians still enthralled by our new toys.”

I wonder how Saint-Ex would describe the current moment, a century since he learned to fly? What would he think of hyper-connectivity and cyber reality in the increasingly bad-tempered and overcrowded global village he helped to create? Our psychology still rocks on its foundations and, more than ever, we are in thrall to new toys. But reading Wind, Sand, and Stars, I find immense comfort in the realisation that I, too, have discovered an implement of unexpected self-discovery. It helps me tap into creative energy and to measure myself against obstacles. This implement takes me to places where I never planned to go and facilitates human encounters I never expected to have. Sometimes it allows me (very briefly) to fly. But it is not machine powered. Nor does it consume precious resources. It keeps my feet much closer—although not always firmly—to the ground. The skateboard is just a plank with wheels, physically more aligned with gutters than stars. But I do believe Saint-Ex might approve, for while my adventures are terrestrial and routine in comparison to his epic, celestial quests, the journey of the heart is one.

* * *

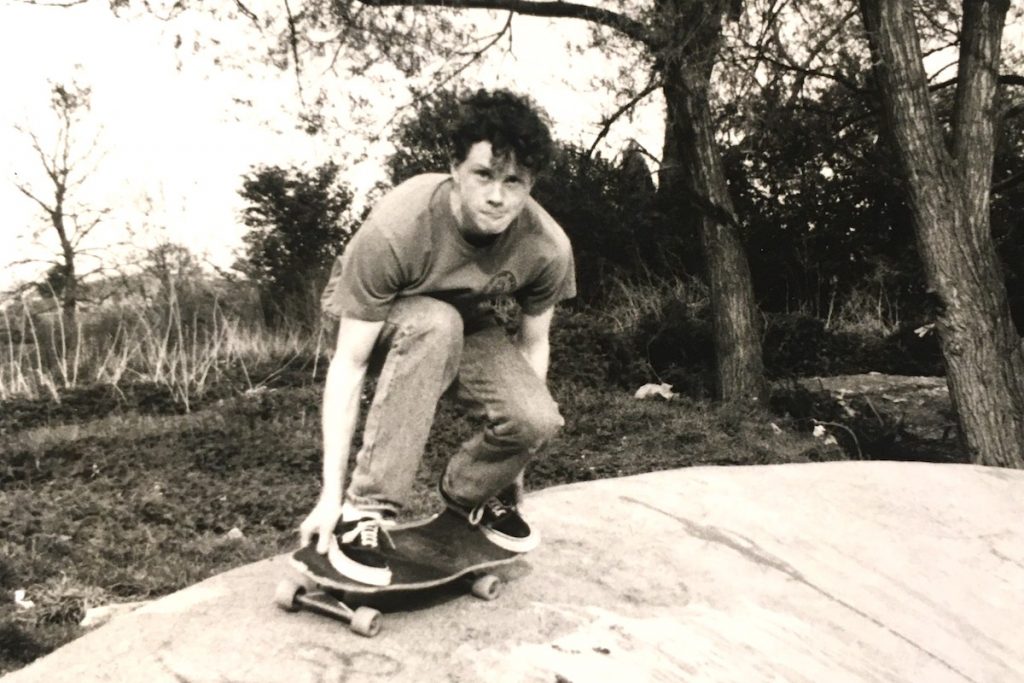

I first learned to skateboard 37 years ago on a short stretch of pavement in London. After peaking in popularity as a 1970s-era craze, the practice had fallen to its lowest ebb in the early 1980s. Skateboarding wasn’t cool anymore. Every second item put up for exchange on Noel Edmonds’s Multi-Coloured Swap Shop, the popular Saturday-morning kids TV programme, was an unwanted skateboard. Most commercial skate parks had closed. Wobbling on the rickety fence between childhood and puberty, I wasn’t cool either. After borrowing a thin plastic skateboard from a friend, I learnt to stand on it indoors. From inside the house, I progressed to the nearest street corner, a long right-handed sloping U-bend. The garish orange object had very hard plastic wheels that easily stuck on tiny pieces of grit, throwing you to the ground. Only after several painful falls did I learn to bend my knees and spread my arms wide. It was worth it. Mastery of the corner guaranteed an uninterrupted cruise down to my gate, wheels-a-clacking, the wind in my face and a warm feeling of accomplishment inside me.

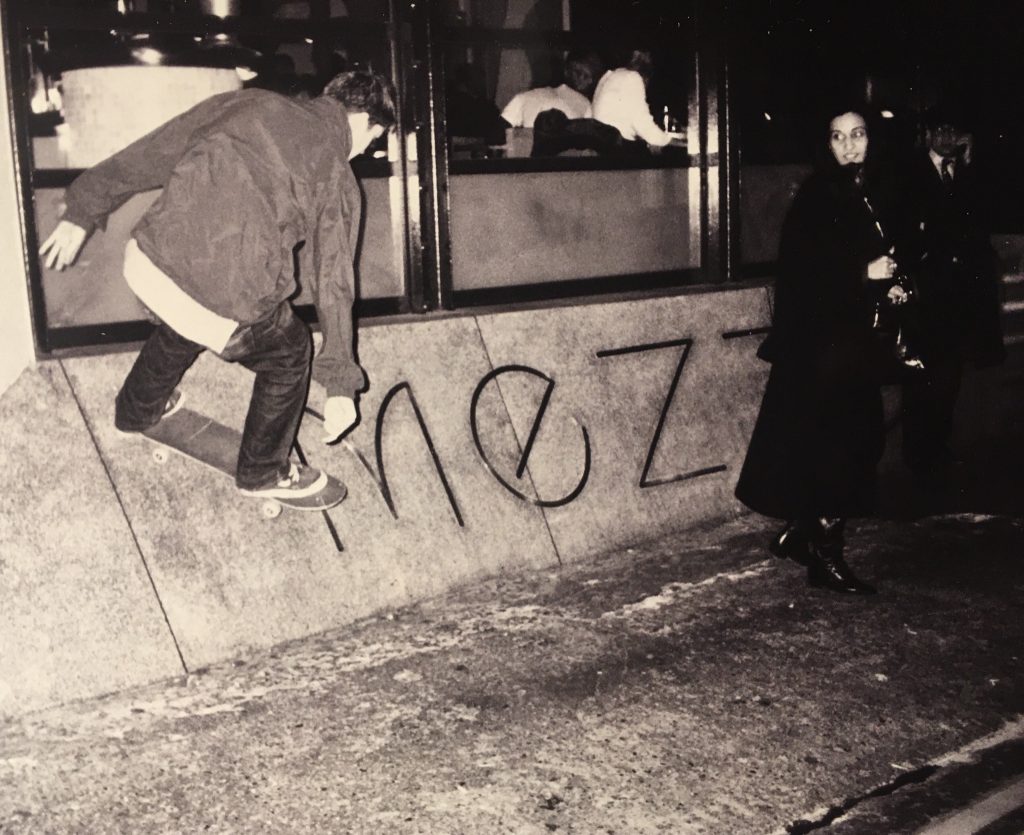

When an older neighbour gave me his wooden skateboard with soft wheels, I could travel further and faster. Without the risk of hard wheels skidding to a sudden halt, I was also safer. From the street corner, I graduated to a nearby hill and then beyond. I started to map out Notting Hill, the part of London where I lived. I met and made friends with other skaters. Every time I went out I mastered a new trick, discovered a new place or encountered someone different.

I began to visit “Meanwhile 2,” a purpose-built skate facility tucked under the Westway near Royal Oak tube station and hence protected from the elements by the overhead flyover. Meanwhile, as we usually called it, consisted of two smooth concrete ditches. It had earned its nickname as younger sibling to a neighbouring 1970s skatepark built in Meanwhile Gardens, a grandly denominated patch of grass by the Grand Union Canal in Westbourne Park. Meanwhile 2 drew a very eclectic crowd. Streetwise west Londoners rubbed shoulders with landlocked surfers. Skate punks from Ipswich and Bristol fraternised with skate brats from Bromley. There were all sorts and no types. A Deptford-based American called Steve hosted occasional and anarchic competitions that, for reasons known only to himself, he called “The Smell of Death.” The skatepark locals were always friendly. In their company, I rapidly improved, learning to push my limits as a skateboarder. Their encouragement—I was often the youngest in the group—helped me grow in confidence.

Although usually welcoming, Meanwhile could also be unpredictable and dangerous. Discarded condoms littered the curbs behind the skateboard ditches, evidence of unsavoury nocturnal usage of our space. Rancid puddles of urine stank in corners. Thug kids frequently hovered in the shadows, hunting for soft touches. They were after money but also your board: a good skateboard was easy to resell. On weekends, when older local skaters were about, the thieves kept their distance. However, on a quiet afternoon, when the place was empty, you might have problems. Knife-wielding assailants sometimes hid behind the Westway’s giant pillars. A friend had ammonia thrown in his face.

Despite the risks, I kept going. And older Meanwhile locals continued to treat me well, keeping me supplied with skate gear. In turn, I passed my used kit on to others. I patched and glued my skate shoes until they fell off my feet. I stayed fit, had adventures, explored London, and made friends. I learned the values of generosity and frugality. I found joy in random acts and improbable places. I was that most rare of urban beasts—a happy, healthy teenager.

But I gradually tired of hurling myself at and off curbs. Approaching adulthood, I grew more self-conscious, especially when clattering noisily down the street. Seeking invisibility, I pretty much gave up skateboarding. But I always missed it.

I attempted to revive my enthusiasm at regular intervals throughout my 20s and 30s. But something always got in the way—work, an unpleasant fall, bad weather—and I would stop again. Thinking about these failed comebacks today, I realise what was missing: I was always alone.

Then in 2014, wandering across a godforsaken piece of reclaimed swampland, wedged underneath a grimy stretch of motorway at the edge of one of Rio de Janeiro’s many favela communities, I came across some skateboard ramps propped against a wall. I had been working with young people in the city’s favelas for a decade, and was intrigued to learn that skateboarders existed in the Maré complex, a crowded urban cauldron of 150,000 inhabitants. Maré—the word means “tide” in English—began as a collection of wooden houses built on stilts over salt marshes at the edge of Rio’s Guanabara Bay. The first residents were fishermen and migrant construction workers from impoverished rural communities in Brazil’s north-east. Today, their descendants live in one of South America’s most densely populated and, tragically, balkanised urban communities. Across Maré, heavily armed criminal gangs wage lethal turf wars with each other and against Rio’s police, who, in response, swoop low over the residential area in combat helicopters, firing into the streets. Fatalities from stray bullets are not uncommon. Which is one reason why the original residents’ grandchildren, some of whom now ride skateboards, might choose to do so underneath a motorway.

Friends informed me that the ramps belonged to a group who met each weekend. Curious as to what favela skateboarders might look like, I took a bus to Maré from my comfortable residence in Rio’s South Zone. Children and teenagers now launched themselves from the ramps I had seen leaning against the motorway pillar. I even discovered the community’s very own Maré Skate Shop. By the end of the Saturday morning, I was wobbling around on a new skateboard with new friends. I returned the following Saturday and the one after that. With assistance from the locals, I relearned old tricks and acquired one or two new ones. Protected from the harsh sun by the flyover above, and drowning in the roar of overhead traffic, I’d unearthed a graffiti-covered corner of Rio that quickly became my tropical Meanwhile 2.

Rio de Janeiro is one of the planet’s most violent cities. The default mind-set of most favela teenagers is fear. In addition to terror of the police, deranged gang members and stray bullets, a deep-rooted dread of the world beyond the favela limits is also common. Rio threatens them, as if at any moment it could swallow them up without a trace. Most favela youth, once they leave the community, become illegal aliens in their own city. I was therefore pleased and amazed to discover that such dread of the outside did not afflict the Maré skateboarders. They travelled to different neighbourhoods in order to skate, making friends who belonged to different social backgrounds. They were among the most confident and sophisticated young people I’d encountered in Rio. The simple wooden instrument was helping them to develop resilience, build friendship groups, and shed the invisible manacles of ghetto mentality in the process.

The threat of physical injury is constant when you’re skateboarding. And so, in order to progress, you must carefully balance the risk against your skills. You must also learn to fall, get up, and try again. Good skateboarders master these processes. It struck me that this might help explain why Maré’s skateboarders appeared well equipped to manage engagement with the outside world.

* * *

Two years after reigniting my passion for skateboarding in Brazil, I returned to the UK to train as a teacher. I was working in a large secondary school in Bradford, struggling as a rookie in this taxing profession. Smelling the inexperience of a trainee, the children all but took me to the cleaners, to begin with at least. Jelly tots, launched by unseen fingers, occasionally soared across the classroom to ping off my desk. A smirking boy propelled a paper airplane into the air and, subsequently, my forehead, holding my gaze as he did so. Teaching was tough going, and a radical gear shift from my laidback lifestyle in Rio.

I studied the work of psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi (pronounced Me-High Chick-Sent-Me-High), who is adamant that the best moments in our lives are not the passive, receptive, or relaxing times. Somewhat echoing the ideas of Saint-Ex, he argues that our greatest moments occur when we are engrossed in a challenge. According to Csikszentmihalyi, at such times the “ego falls away. Time flies. Every action, movement and thought follows inevitably from the previous one, like playing jazz. Your whole being is involved, and you’re using your skills to the utmost.” Csikszentmihalyi calls this state of optimal experience “flow.” But while I endeavoured to create flow in lessons—a guaranteed winner according to my mentors—I rarely, if ever, succeeded.

Overwhelmed by work and low on friends, I missed Brazil. But I had a skateboard. And I found an outlet at a nearby self-built skatepark, wedged between a canal and railway line on an abandoned patch of Yorkshire concrete. DIY culture has become an integral component of skateboarding in recent years. Today’s purpose-built skateparks are often overcrowded and too-closely monitored. Consequently, many independent-minded skaters have opted to erect their own self-financed projects in forgotten spaces, bringing life to unloved urban nooks. Here, I left my fledgling teacher persona in the car. The weather was rarely accommodating, and it was a far cry from Rio. But at the Shipley DIY, I snatched brief, reinvigorating moments of distraction and enjoyment.

One Friday afternoon after school, while repeatedly trying and failing to learn a new trick, I fell and hurt myself. A fellow skateboarder reminded me that, in order to learn new moves, it helps if you are “stoked”—an ancient piece of skate and surf slang signifying that feeling when your blood is pumping with enthusiasm. According to Urban Dictionary “being stoked is the epitome of all being. When one is stoked, there is no limit to what one can do.” To be stoked, in other words, is to achieve flow. And I feel that Csikszentmihalyi (who said that he experienced flow while “rock climbing, cooking, painting, and playing chess“) would approve.

I also sometimes visited an official council-built skate facility in Leeds’s Hyde Park on weekends, where I made more friends, including the generous owner of Welcome Skate Store. Come the school holidays, when I made trips to Brazil, he supplied me with used equipment to donate to Maré’s skateboarders. Then, shortly before qualifying as a teacher, I discovered the existence of Make Life Skate Life, a Belgium-based organisation that mobilises teams of volunteers to build skateparks—bigger, more beautiful versions of the Yorkshire DIY spot—across the globe. I contacted the group’s founder and, after qualifying as a teacher (there were fewer airborne jelly tots in the second year) I returned to Rio with a new plan: to build a skatepark in the favela.

However, we could not simply occupy the space. In order to build a skatepark in Maré, we needed multiple authorisations—not just from local government and the company responsible for the motorway that ran over the site, but, crucially, from the criminal gang that ran the area. The road company said they didn’t mind as long as it was okay with government. The mayor’s office sent an architect to visit the proposed site, and looked at our plans approvingly, even while inquiring whether we’d secured permission from the local unofficial powerbrokers.

To complicate matters, a mid-ranking criminal, who ran an unofficial transport service in the community, used our site to park his vans. A large metal container, occupied by his drivers, sat squarely in the middle of our would-be skatepark. We could build only if he agreed to move the container, which would require a crane. He said he would move the container only if his own boss asked him to do so—which meant we needed endorsement from the top. In Rio, such a person is called the dono, literally owner, of a community. But tracking him down proved difficult. We were told that he didn’t sleep in the same place on consecutive nights, nor carry a mobile phone.

Meanwhile, a team of international volunteer builders from Colombia, the United States, France, Germany, Denmark, and the UK, who all paid their own way to Rio, were on their way to help. We were to provide them with meals and accommodation in the favela. Supporters from Rio, both inside and outside Maré, were mobilised. Saturday skate classes were fully registered. Everything was set, but we still hadn’t spoken to the dono. This was apparently related to the fact that a TV crew had been filming in Maré, and so he was careful to be off the streets. Without his consent, we couldn’t begin.

The go-ahead came at the last minute, when I was already at the airport, waiting to pick up the first volunteer builder, a Frenchman named Camille. “He [the dono] just wants to see the accounts when we finish, to make sure we’re not stealing anything,” the caller told me. Oh, the irony.

The next day, the mid-ranking gangster rustled up a crane and moved his container. The build went ahead in a happy, chaotic flurry of dirt, brick, rubble, sand, metal, and cement. I was amazed by the skill, dedication, and sense of comradery among the volunteers, who took only two days off during the month needed to complete the job. When we’d finished, and the builders were taking their first runs around the smooth curves and slopes sculpted underneath the motorway pillars, I was delighted to hear it described as a “flow park.” A few months later, at the end of 2019, Sky Brown, global child skateboarding phenomenon, visited the favela with her younger brother Ocean. Their presence provided the next generation of girls and boys learning to skate in Maré with a joyful, indelible experience.

I wasn’t around to share that moment. I’d already left Rio de Janeiro on my way to begin a new life in Nairobi. With time to spare en route to East Africa, I travelled to Palestine to volunteer with Skatepal, a small non-profit dedicated to promoting skateboarding in the West Bank. Alongside Make Life Skate, it’s one of a burgeoning number of grassroots peer-to-peer skate-development outfits springing up across the globe. Issues faced by Palestinians and favela residents are similar yet different: While the favela is not physically fenced in, the West Bank separation walls are real and high.

Fellow volunteers came from Canada, the United States, and the UK. Once again, I found myself alongside creative, altruistic individuals working to bring relief and hope to a corner of the world afflicted by prejudice and violence. In Asira, the small town outside Nablus where we were based, the local community embraced us, inviting us to join walks, family meals, and olive-picking expeditions. Two of the volunteers, young women born to parents in exile, were visiting Palestine for the first time. Fluent in Arabic, they formed strong bonds with the local girl skaters. The growing presence of girls and women in skateparks across the world has breathed fresh life into 21st century skateboarding, helping to make such places more carefree and inclusive, and less the testosterone-heavy arenas they sometimes can be.

Unfortunately, while skateboarding can bring oxygen to communities suffocated by violence and isolation, it is no magic bullet. Nor can it always build bridges. I was sad, though not surprised, to learn there is currently little or no contact between Palestinian and Israeli skateboarders.

* * *

Saint-Ex, who believed as much in the power of friendship as in the value of implements, also wrote that “there is only one true form of wealth, that of human contact.” Thanks to my modest plank with wheels, I make friends through skateboarding wherever I go. When I visit family in England, I now skate at Meanwhile 2 on Sunday mornings together with ex-pat American dads on the cusp of middle age. Whereas I was once the youngest at the skatepark, I am now this group’s most senior member.

The first time I went skateboarding in Kenya—at a skatepark built by a German organisation called Skate-Aid—I met Balo and Mwangi, two former street kids who once dwelled in a ditch next to a skate spot in downtown Nairobi. The two urchins, who kept watch on the skateboarders’ belongings in exchange for rides and coins, soon learned to skate. Before long, the two were out-performing the regulars, who got organized, took them off the streets, and found them a home, guardianship, and schooling. Today, in their mid-teens, they are two of Kenya’s best skateboarders.

When I think of Balo and Mwangi, I remember that at the end of Wind, Sand, and Stars, Saint-Ex, observing a child in a train full of sleeping Polish workers, describes the bittersweet sensation of identifying the “Mozart” he sees in a face promising a “life filled with beauty.” Tragically, he reflects, because of poverty, that child’s life will never fulfil its potential. And looking around the carriage of snoring workers, the “murder of Mozart” in all of them torments him.

At face value, a skateboard is a toy. But as an implement, it can change lives for the better and help to kindle the dormant creative embers that lie inside all humans. I have been privileged to see this magic at work among the young men I first skated with as teenagers in Maré seven years ago, as I observe them, in difficult circumstances, develop into young adults. They are resourceful and inventive, many of them involved in music and visual arts. The entrepreneur of the group, who opened his own haircutting salon, has great flair. He and his friends now tutor the next generation on Saturday mornings.

Skateboarding is simple and complex, pointless and transformational. It has taught me that by doing something for the sake of it, without any expectation of compensation, I can reap priceless rewards: self-esteem, happiness, health, and friends. And that is a great consolation, especially when I find myself flat on my back after a fall on a Saturday morning, in painful contemplation of the African sky.