COVID-19

COVID-19 and the Ongoing Global Workplace Revolution

The pandemic has done much to undermine the basis for urban supremacy.

For most of the recent past, economic geography has shifted to ever-larger cities across the globe. By the end of the last decade, many were convinced that we were entering a supreme era of the glittering, high-rise “superstar” city that would inevitably swallow all the best bits of the economy, and serve as unparalleled centers of tech, culture, political activism, and global trade. Globally, the ranks of city-dwellers more than doubled over the last 40 years, from 1.5 billion in 1975 to 3.5 billion according to data from the OECD.

Yet now this urban-centric pattern may be slowing, and even reversing. Three critical factors are at play here. First, of course, the pandemic has weakened the appeal of urban life by the very logic of social distancing and higher levels of infections and fatalities. The second factor has been an alarming uptick in urban crime and disorder, particularly in the United States but elsewhere as well. Finally, there has been a move to dispersed and online work, which enables people and companies to shift their work to more remote locations.

This development, of course, will be resisted by various groups, notably urban real estate investors, green ideologues, and the cultural Left, all of whom are heavily concentrated in the biggest cities. When in political control, as they are now in America, entrenched urbanistas will work against decentralization by limiting automotive mobility and undermining energy dependent industries such as manufacturing, agriculture, and fossil fuels, all of which depend on reliable, affordable energy.

Peasant rebellions: A quick history

Conflicts between the countryside and the metropolis have been a staple of history since the days when Semitic tribes overwhelmed the civilized Sumerians. Often the rough outsiders enjoyed the benefits of greater unity, less debilitating luxury, and better military tactics. Goths, Huns, Mongols, Afghani Muslims, or Ottoman Turks conquered such great centers of civilization as Rome, Baghdad, Delhi, Beijing, or Constantinople. They usually ended up seduced by the attractions of city life, becoming progressively less fierce and more urbane.

In some cases, local peasants constituted a greater threat, particularly in the later Middle Ages as seen in insurrections like the French Jacquerie of 1358 1 and the large English uprising led by Wat Tyler in 1381.2 Even in early America, George Washington had to repress Shay’s Rebellion led by anti-tax farmers in order to preserve the shaky Republic. Arguably the most sanguinary revolts took place in Russia, driven by Ural Cossacks under Emelian Pugachev in 1773, followed by 550 others that failed, but in 1917 the peasants finally succeeded by supporting Lenin’s seizure of power. When the Soviet regime began to confiscate land for collectivization, the property-loving muzhiks rebelled, only to be ruthlessly put down by reconstituted, if red, urban elites.3

The Taiping rebellion in 1843 may have been the most lethal. The rebels called for the overthrow of the Manchu Ch’ing dynasty, land reform, improvements in the status of women, tax reduction, the elimination of bribery, and the abolition of the opium trade. The rebellion was finally put down more than a decade later, but the Taiping program would later be adopted by Sun Yat-sen, who would overthrow the imperial regime, and then by Mao Tse-tung and the Communists.4 Mao deployed peasant soldiers to surround cities controlled by his opponents. The peasant army ultimately succeeded, but largely illiterate and lacking access to information, they ultimately paid the price for their enthusiasm, as the Communist elite in Beijing imposed policies that led to mass starvation and impoverishment for millions.

The pandemic undermines the urban stranglehold

The pandemic has done much to undermine the basis for urban supremacy. For all the blandishments of the urban density lobby, COVID-19 continues to do its worst work in dense urban areas, particularly poorer ones. The association between urban density, poverty, and disease persisted through the Renaissance and the Industrial Revolution—its pandemics were well chronicled by Engels—to the Spanish flu a century ago.5 Despite the pandemic’s relentless spread elsewhere, fatality rates around the world tend to be worst in places with the highest urban densities, particularly those with overcrowded housing, mass transit dependency, and deep pockets of poverty.

In the United States, counties with urban densities greater than 10,000 people per square mile constitute just three percent of the nation’s population but have suffered 8.8 percent of deaths associated with the pandemic—nearly three times their proportional share. By comparison, in the most typical suburban areas (urban densities of 1,000 to 5,000 per square mile), where 81 percent of the metropolitan population lives, the COVID fatality rate is 60 percent lower. This pattern can be seen elsewhere, such as in the United Kingdom and even Japan, where urban areas have suffered much higher rates of fatalities.

The most likely cause here is “exposure density” brought about by crowded housing, transit, elevators, and office environments. These challenges will likely not end even with a vaccine or herd immunity. As Laurie Garrett pointed out three decades ago in The Coming Plague, the growth of crowded megacities—or what she calls the “urban Thirdworldization” evident in China’s dense and unsanitary cities—is ideal for creating new pandemics like SARS, MERS, and swine flu.6 The National Institute of Health’s Anthony Fauci sees potential new viruses already incubating in China while some health experts suggest COVID-19 will plague our society for years and even decades.

Growing urban disorder

The growth of class divides predates the pandemic and arguably represents the greater challenge to urban supremacism. These gaps have widened as the worst effects of the pandemic have been felt in impoverished parts of New York, Houston, Los Angeles County, Chicago’s poor south side, and similar areas. The Bronx and Brooklyn, for example, have suffered an 80 percent and 50 percent worse death rate respectively than denser yet wealthier Manhattan.

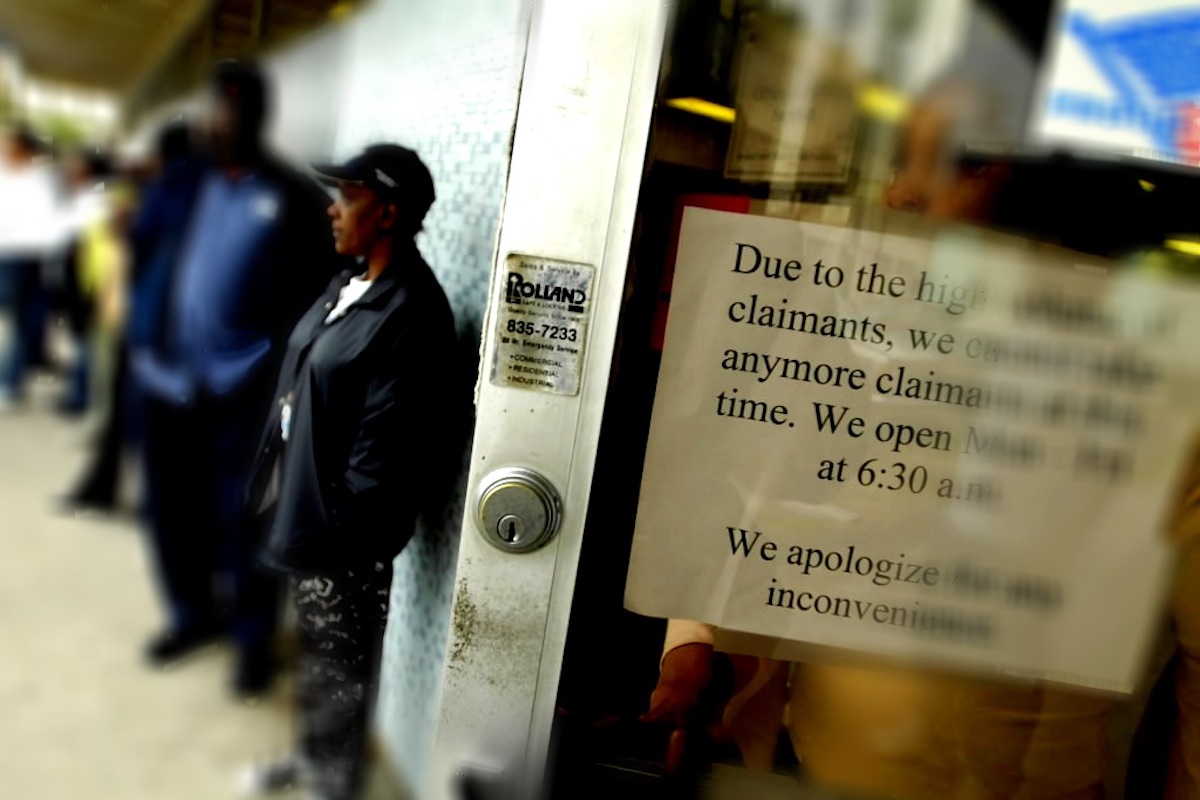

The lockdowns, whether justified or overwrought, have pummeled these low-income workers. Roughly half of all job losses in April were in low-paying fields such as restaurants, hotels, and amusement parks. Almost 40 percent of Americans making under $40,000 a year have lost their jobs, and the wage gains made during the first two years of the Trump Administration have evaporated.

This is also the case outside the United States. Diverse, dense, and largely poor Barking and Dagenham in East London have the two highest COVID-19 infection rates in the country. In Paris, the Banlieue of Saint Denis, long a synonym for inequality, suffered a 130 percent excess mortality rate compared to 74 percent in the richer Paris inner city.

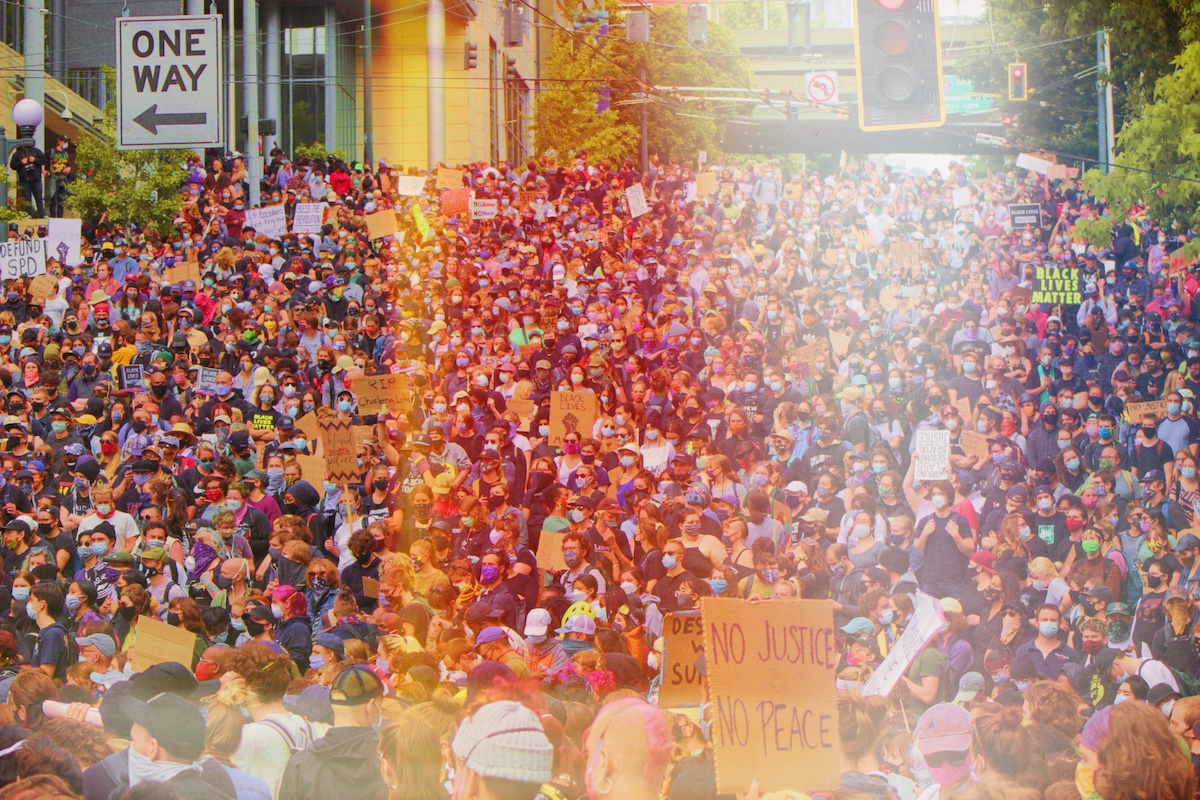

Given the stark inequities, it is not surprising that crime has been inching up in cities around the world. The rioting and demonstrations in Portland have left its downtown largely bereft of pedestrians. The same is true in London and Paris, while resistance to the lockdowns has been greatest in already marginalized minority communities. On January 27th, 2021, French restaurant owners refused to comply with the lockdown orders and staged a mass opening. Similar events took place in Spain, Poland, and Italy. In early 2021, a series of riots broke out in 10 cities in the usually peaceful Netherlands. Mobilized through social media networks, the protestors took to the streets and clashes with the police inevitably broke out. The authorities condemned this behavior as “criminal.”

But the most explosive powder keg may be in the cities of the developing world, where poverty was already rife, and the pandemic is likely to last longer due to lack of vaccines and decent healthcare delivery. Last year, South Africa experienced an increase in the country’s already long history of violent protests—one protester in Johannesburg held a banner bearing the slogan “Freedom from Hunger,” and in Cape Town a protest organized by the disenfranchised colored community movement “Gatvol Capetonians” overwhelmed the police, even though they were armed with stun grenades and rubber bullets.

Civil unrest has also spread in cities in Nigeria, Egypt, and India’s Gujarat state, where hundreds of migrant workers deprived of their income were seen clashing with and throwing rocks at the authorities. Prime Minister Modi’s government has used the COVID-19 opportunity to implement market reforms which produced an explosion of farmer protests in the bigger cities. The government responded with a heavy hand, cutting off the Internet in the city of New Delhi. The peasants, including those living temporarily in cities, are brandishing their digital pitchforks.

Is the online revolution a game-changer?

The global shift to big cities was predicated on the notion that, to run a sophisticated business, one had to relocate there. Most urban economies, particularly in the West, depend largely on the clustering of educated professionals, but in the wake of the pandemic and the riots, many have found a home in the “city of bits” laid out by MIT’s William Mitchell almost a quarter-century ago.7

Technologies that barely existed at the time of 9/11 are now widely deployed within banks and leading tech firms, including Facebook, Salesforce, and Twitter; all expect a large proportion of their staff to continue to work remotely after the pandemic. This shift has reaped unanticipated productivity gains according to one study of European companies, cutting operating costs by roughly one-third. A recent University of Chicago study suggests as many as 34 percent of American workers could do their jobs remotely.

These patterns can be seen globally. Based on OECD estimates, after the pandemic, some 128 million workers will not need office space, which could lead to a reduction of 2.3 billion square feet per year. A survey conducted by France Info shows that the number of people who now work from home had increased by 24 percent by September 2020, and more than half of respondents said they would like to be given the opportunity to continue to work from home once the pandemic ends.

Working from home is also prevalent in other high-income countries. According to a report from the Office of National Statistics, Ireland is considering legislation that will allow workers to labor at home as a “right.” In Australia, efforts to get workers back in the office have largely failed and the transit system connecting neighborhoods to the inner city has lost half its commuters. These patterns may alter once the virus is contained, but home-based work is likely to remain far more prominent in the future.

Even in ultra-dense places like Hong Kong, the online trend is being widely embraced by the city’s powerful banks. In Singapore, arguably the best-run crowded city in the world, close to 80 percent of workers prefer to work at home full or part time. Much the same can be said of cities in South Africa, where a survey of 200 employees found that 53 percent of respondents do not expect to return to the office on a full-time basis and over half felt they were more productive when working from home. The study reported that only 26 percent of the respondents in SA had the freedom to work from home before the COVID-19 crisis. Due to the lockdown, that number increased dramatically, with 79 percent of the respondents working remotely.

The re-discovery of the periphery

This move online is driving a shift to the urban periphery and beyond. A recent report from Upwork finds that between 14 and 23 million Americans are seeking to move to a less expensive and less crowded place. Perhaps more revealing: three-quarters of venture capitalists and tech firm founders, notes one recent survey, expect their ventures to be totally or mostly operating online. According to a study by Big Technology, the largest gains in tech workers since the pandemic are Madison, WI, Cleveland, and the suburbs around New Haven, while New York City, San Francisco, Boston, and Chicago have taken the biggest hits.

Once urban real estate was highly prized, but today the hottest US zip codes, according to Realtor.com, are not in Manhattan but in places like Colorado Springs, Reynoldsburg, Ohio, and Rochester, New York. Prices may be dropping in Manhattan, the core of San Francisco, Los Angeles, and Seattle, but things are looking up in these cities’ suburbs and exurbs as well as in areas like Fayetteville, Arkansas. Some smaller cities, such as Fargo, Sioux Falls, and Huntsville are also beneficiaries of these trends. Roughly half of all Americans, notes Gallup, want to live in a rural area or small town, although it’s likely many won’t actually take the plunge for family or other reasons.

During the first lockdown, almost 20 percent of the Parisian population fled to the countryside but the escapist trend has been building for years. Over the last decade, according to a 2019 report by INSEE, the less dense communes gained in population, while the denser inner ring of Paris depopulated. A July 2020 survey conducted by the French housing website SeLoger showed that, given the choice, the French population would prefer to live in smaller towns such as Aix en Provence, Bordeaux, Nantes, and Toulouse. The densely populated Paris does not make the top 10 of the list.

In the UK, Ernst and Young forecasts that between 2020 and 2023 the fastest growing cities will be places like Nottingham, Bristol, and Cambridge—as opposed to densely populated London. In part due to the pandemic and Brexit, London’s population is set to decline for the first time since 1988 according to a report from PWC, as many workers are now reassessing their options and working remotely. The report found that up to 16 percent of London’s population, which has fallen by a reported 700,000 since 2019, would consider moving away permanently given the opportunity to do so.

Similar patterns can be observed in South Africa. In December 2019, the town of Polokwane almost ran out of water because the government did not foresee these new developments. A 2019 report by the website Property24 shows that South African city folk are increasingly buying property in smaller rural towns as a second option. A December 2020 report from First National Bank found increased interest in making former holiday homes in places like Ballito, Knysna, St Francis Bay, Port Alfred, and Jeffreys Bay a primary residence in a trend known as “semigration.”

The coming political battle

The ongoing revolution in work seems likely to create a new political reality. It’s not only the affluent and old headed to the periphery. Economically vital populations, notes demographer Wendell Cox, like the foreign-born and millennials, are now increasingly heading to smaller, less dense places like Jacksonville, Salt Lake City, Sacramento, and Kansas City. Similar pressures, notably high housing prices, are now driving millennials in France, the UK, and South Africa to consider new locales.

Having gained a seat at the table of the information economy, the periphery may be better positioned to make its political case. The periphery has largely been seen as reactionary, identified with things such as Brexit, France’s National Front, or the election of Donald Trump. But attempts by progressive regimes to eliminate fossil fuels may not be so popular when educated newcomers discover—in New Mexico, for example—that their school funding depends on oil revenues. Large swaths of regions now popular with knowledge workers from Appalachia to The Rockies could experience massive job losses for a climate agenda supported in large part by Wall Street, Silicon Valley, and the cultural icons, turning even vital smaller towns into instant slums.

Living in the periphery, some knowledge workers may change their priorities; attempts to stamp out driving might seem reasonable in Manhattan or the Isle de France, but they are less likely to be embraced by the residents of a small exurban village or rural area. These people may resent how much they must bear the costs of environmental piety, particularly since, as a recent study in Ecological Economics found, green energy policy hits rural communities in Germany much harder than cities, even though they are “on a par” with big cities in terms of greenhouse gas production.

Unsurprisingly, many rural and exurban residents have rallied against urban-driven energy policies, particularly attempts to wipe out affordable natural gas and raise energy prices across the board. This was a major reason behind the gilets jaunes protests in France and similar protests in the Netherlands. There is also a class element, as the green war against affordable energy will be felt most by the poor as levels of fuel poverty have been on the rise in Greece, Germany, France, as well as in the United Kingdom.

The conflict in the developing world, where much of the world’s rural population lives, could become even more fraught. Deregulatory policies that would reduce food prices in cities have sparked violent outbreaks among Indian farmers, coordinated on the Internet, while others have protested attempts to force farmers around Delhi to stop burning stubble while cars, factories and other sources of pollution are largely ignored.

Is there a better way forward?

A shift back to the countryside is also emerging now in China and India, and represents an opportunity to create a more sustainable society, both socially and environmentally. Rather than seeing the periphery as inherently destructive, the new geography of dispersion could help reduce traffic congestion, a primary source of greenhouse gasses, and reduce the urban heat island effect by spreading out population and industry. Future renewable energy depends on rural locations; it is hard to imagine heat-generating solar plants or windmills scarring the urban terroir of Paris, Manhattan, or San Francisco.

But more importantly perhaps, the shift to the periphery allows us to begin rebuilding the middle class by expanding home ownership and beginning to reverse the rapid aging and demographic declines—including a dramatic drop in marriages—associated with big and densely packed cities. It could also be part of a humane redistribution of wealth and power. With their growing appeal to the educated classes, more rural areas could jettison their current tendency to embrace resentment and conspiracy theories and become a greater part of creating a better human ecosystem.

Once thought as marginal and hopelessly antiquated, a revived countryside can not only bring areas back to life that have been losing out for generations. It also offers the world a vital assist in creating a healthier, more humane, and socially sustainable future.

References:

1 Barbara Tuchman, A Distant Mirror: The Calamitous 14th Century (New York: Knopf, 1978), pp 176–82.

2 “Tyler, Watt,” The Columbia Encyclopedia, 6th ed., ed. Paul Lagassé (Columbia University Press, 2000).

3 Nicholas Riasanovsky, A History of Russia (New York: Oxford University Press, 1963), pp 287–89, 410; Richard Pipes, Russian Under the Old Regime (New York: Penguin, 1974), pp 155, 169–70; Orlando Figes, A People’s Tragedy: The Russian Revolution, 1891–1924 (New York: Penguin, 1996), pp 754–75, 764.

4 Kenneth Scott LaTourette, The Chinese: Their History and Culture (New York: MacMillan, 1967), pp 284–86, 292–94.

5 William McNeil, Plagues and Peoples (Garden City, NY: Anchor Press, 1976), p.168; John Barry, The Great Influenza, (New York: Penguin, 2004) ,p.276, p.359, p.373; Fredrich Engels, The Condition of the Working Class in England in 1844, New York, 1887

6 Laurie Garrett, The Coming Plague: Newly Emerging Diseases in a World Out of Balance, (New York: Penguin, 1994), p.509, p.620

7 William Mitchell, City of Bits: Space, Place, and the Infobahn, (Cambridge, MA; MIT Press, 1997, p. 96