Art

Carl Th. Dreyer's 'Day of Wrath' and the Power of the Punished

It is difficult to believe in heaven, but it is also difficult not to believe in a heaven.

NOTE: This essay contains spoilers.

Part of what makes Carl Theodor Dreyer’s greatest films so rewarding is their moral ambivalence. The Danish director’s oeuvre spans several decades, from the 1910s to the 1960s, but it was in his final three feature films, Day of Wrath (1943), Ordet (1955) and Gertrud (1964) that this theme became fully apparent. Gertrud can be read as a feminist liberation story or a compelling case against sexual liberation. Ordet might be an expression of religious truth, but it might also be anti-theist (it might even be both). Day of Wrath may be about the cruel persecution of innocent women accused of witchcraft, but it can also be read as a story about the evil of witches and the strange benevolence of their flawed persecutors.

I sympathise with Dreyer’s uncertainty. It is difficult to believe in heaven, but it is also difficult not to believe in a heaven. This paradoxical sensibility appears repeatedly in Dreyer’s work. He speaks for the undecided—those who see something wondrous but are blinded and confused by it; those who sense something frightening or malevolent but can see only its vague outline in the shadows; those who know they are moving towards something, but cannot work out what it is. He speaks for those who look at a situation in all its maddening complexity and say, “There is something very important here, but what is it?”

This sense of mystery in Dreyer’s films always surrounds questions of belief. Belief in the supernatural, belief in resurrection, belief in one’s own liberation. In Ordet, a man believes himself to be Jesus, a community is divided by religious belief, and a child’s pure belief in miracles ends the film. In Gertrud, a woman is motivated by a belief in herself and her passions. And in Day of Wrath, everyone believes in witchcraft, even the accused witches themselves.

We never witness anything unambiguously supernatural occurring in Day of Wrath, but the film is filled with eerie coincidences and malevolent intent, and we are left in wonder at the power of human desire and will. Anne (based on the real-life 16th-century witch, Anne Pedersdotter) is the daughter of a suspected witch, and the young and lovely wife of the aged village pastor Absalon. Her desperate and carnal desire for love is repeatedly rejected by her husband whose feelings are bound by religious duty and doctrine. In this pitiable state, Anne begins to hope that she may possess her late mother’s supposed power “to call the living and dead.” And so, in her thirst for lust and revenge, she whispers into the night sky for her adult son-in-law Martin to come. Moments later, he enters the house. Towards the end of the film she tells Absalon, “I wish you dead. Dead!” and he dies in front of her. Earlier in the film another, older witch tells one of her torturers that, “If you send me to my death, you shall follow,” and days later he succumbs to an illness. The same witch says Anne will burn at the stake and she does. Whether or not these events are supernatural doesn’t change the frightening but intoxicating idea that we have more power than we think.

Of Dreyer’s last three films, it is Day of Wrath to which I have repeatedly returned. Because it was made during the National Socialist occupation of Denmark, many critics have speculated that the witch-hunts it dramatised were intended as an analogy for the contemporary persecution of Europe’s Jews. I do not, and nor did Dreyer (if he is to be taken at his word). Anne is not a helpless innocent—she is spiteful and cruel and believes in the power of witchcraft. The more oppressed and unhappy she feels, the more she wants to become a witch. She reminds me of a political extremist—those societal outcasts singled out for their dangerous behaviour, who feel empowered by their infamy. Anne never says as much (Dreyer would never ask a character to explain themselves), but part of what makes her manner so frightening is the growing satisfaction that she takes in the fear she inspires in others. The witches become more certain in their abilities and their attitude, and more willing to believe in their superiority over others and to excuse their own evil.

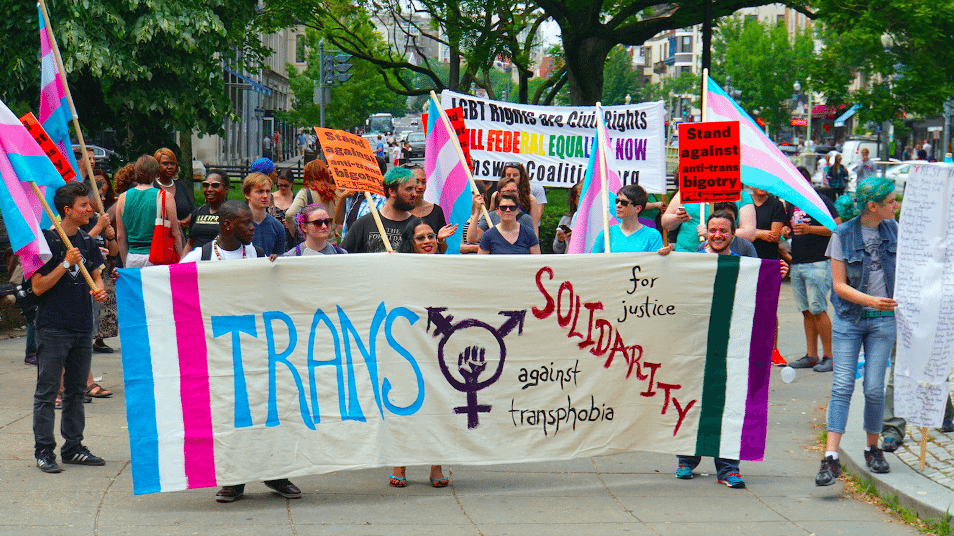

Dreyer uses his story to explore the secularised Christian belief that those who are persecuted, ridiculed, and maligned are presumptively on the side of truth and virtue, and that this provides them with greater moral authority than their tormentors. When we find ourselves on the receiving end of mistreatment and abuse, we tend to reconstitute our pain as pride and believe that we are the powerful ones. This is perhaps why some of the most unhappy examples of our species are attracted to extreme political factions or fringe social movements.

But there are plenty of others who feel more powerful as part of the majority (or at the least as part of the dominant group). Some have majoritarian instincts, others are unduly influenced by the powerful. In Day of Wrath, we also see the potential dangers of a common and unchallenged moral purpose—not merely in the actions of those in authority, but also in their followers who allow themselves to become complicit in what ought to be morally repellent behavior. Multitudes are more pliable than individuals, which is why once a convention has been established, it can be incredibly difficult to undo.

Dreyer’s distinct cinematic style is slow and brooding and often chillingly quiet. His films moved faster when they were silent—his 1928 classic The Passion of Joan of Arc is intense, and arguably the most dramatic of his films. Sound changed everything, even though Dreyer uses very little of it. In a silent film, true silence is seldom possible, as silence is the absence of sound, and silent pictures are usually accompanied by a score from start to finish. But in his talkies, Dreyer makes very effective dramatic use of long pauses between dialogue during which the empty soundtrack weighs on characters and audience alike. He was interested in what has been ignored, what has been neglected, and what is left unsaid. There is so much grievance, misery, and joylessness to be seen, but it is seldom more than implied—a sort of quiet oppressiveness, emphasised by Dreyer’s claustrophobic sets. This is most evident in Anne’s eyes, which the camera seems to follow, and which are surely among the most unforgettable in cinema. Martin, her son-in-law and lover, notices this:

Martin: Anne, you’re crying.

Anne: I’m seeing you through tears.

Martin: Tears I am wiping away… No one else has such eyes.

Anne: What are they like? Innocent, pure and clear?

Martin: No. Deep and mysterious. But I see into their depths.

Anne: What do you see?

Martin: A trembling, quivering flame.

Anne: Which you have lit.

This misery is shrouded in silence. Her husband possesses many strong and admirable traits, none of which he directs towards his wife. He is not unkind, but there is no romance or affection. Anne is neglected, almost ornamental; she is unloved, unappreciated, and never understood—an awful and dangerous combination. No hand of love is offered to Anne. Her husband is dutiful but cold; her mother-in-law sees her for what she is, and hates her for it; her husband’s son shows her sexual attention, but this is only the product of lust, not love. The horrors of the fire, the torture, and the oppressive passionlessness all contribute to the sum of evil in the world, a smoldering pile from whose fumes the witches draw their power. Nevertheless, Dreyer is uninterested in a trite narrative of injustice. Not once do the witches deny they are witches—on the contrary, they are defiant. The clergy and various officials are distant, fanatical, and hypocritical, but are they entirely wrong?

At the end of the film, Anne sheds tears over Absalon’s open coffin. She confesses her guilt and displays her suffering, and the onlookers stand apart from her. They consider themselves blameless and her persecution morally justified, even though compassion, understanding, and the pursuit of the common good have been forsaken in her destruction. Anne’s final words are beautiful, and capture the complexity and ambivalence that pervade the film. As she stands over the body of her husband, she says:

Absalon… So you got your revenge after all. Yes, I murdered you with the help of the evil one. And I have lured your son into my power with the help of the evil one. Now you know… Now you know. I’m seeing you through tears, but nobody is coming to wipe them away.