Top Stories

Return of the Strong Gods: Understanding the New Right

A great many Americans held their noses to vote for Trump, whom they saw as the lesser evil.

And what rough beast, its hour come round at last,Slouches toward Bethlehem to be born?

~W.B. Yeats, “The Second Coming”

In mid-November, just two weeks after one of the most contentious elections in American history, Democratic National Committee member David Atkins took to Twitter. “No seriously… how *do* you deprogram 75 million people?” he wondered, sounding more like a member of the Politburo than the DNC. “Where do you start? Fox? Facebook? We have to start thinking in terms of post-WWII Germany or Japan.” He continued: “This is not your standard partisan policy disagreement. This is a conspiracy theory fueled belligerent death cult… the only actual policy debates of note are happening within the dem coalition between left and center left.” As the comments flooded in, Atkins doubled down: “You can’t run on a civil war footing hopped up on conspiracy theories… without people trying to figure out how to reverse the brainwashing.”

What is most striking about Atkins’s comments is not his evident belief that 75 million Americans are conspiracy theorists, nor his suggestion that we re-educate citizens for wrongthink—in the world of Left-Twitter, this is comparatively mild fare—but rather his insistence that the Democratic party is a uniquely heterodox space, a forum for robust policy debates, while the GOP is some kind of monolith. A “cult,” as he called it. And yet, the Republican Party possesses more viewpoint diversity and is more internally factional than its competitor by a wide margin. Of all the exhausted canards one hears from liberals and never-Trumpers alike, the one that most needs retirement is the notion that Trump bent conservatism to his will, or, as Tim Alberta put it in 2017, “The conservative movement is Donald Trump.”

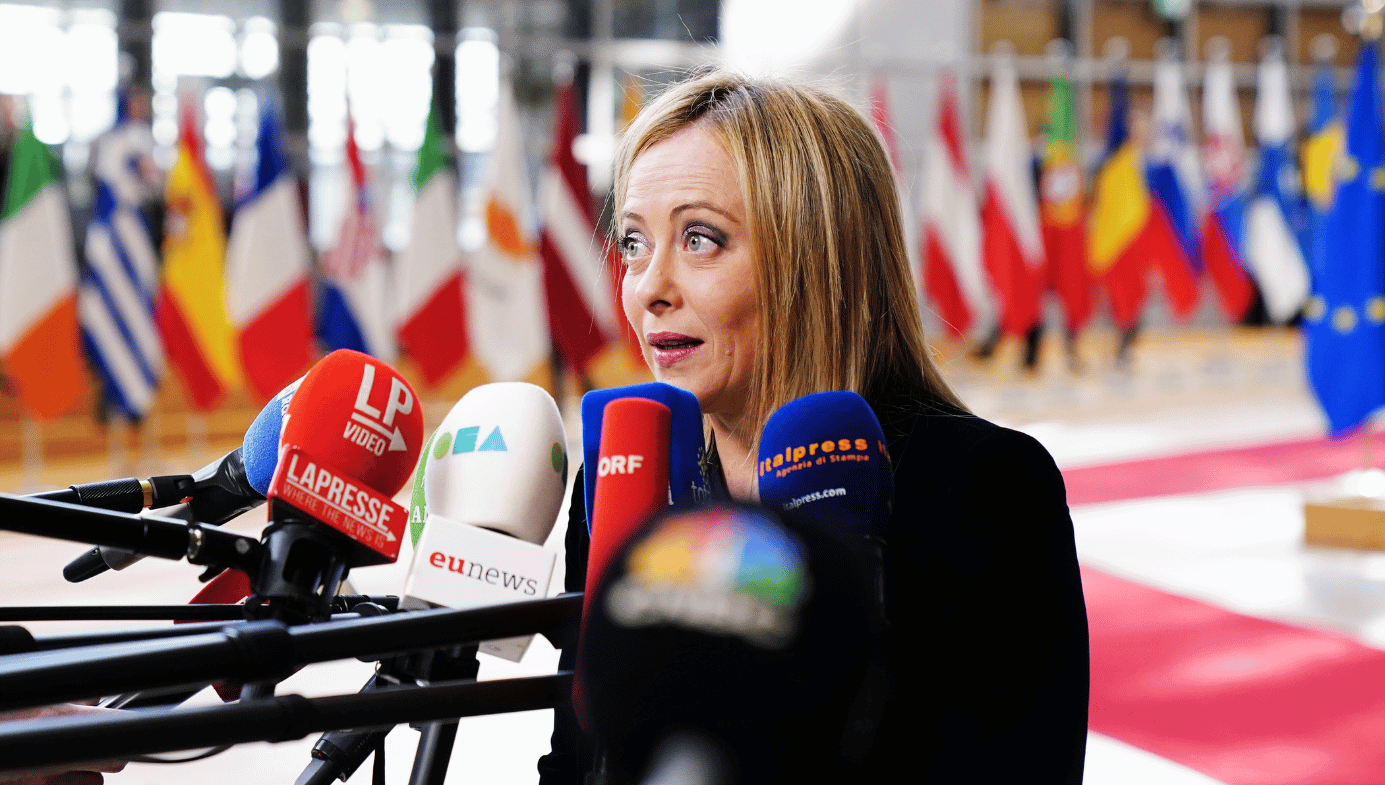

Trump’s election in 2016 was not the reflection of a unified coalition, but a deeply divided one. A great many Americans held their noses to vote for Trump, whom they saw as the lesser evil. Atkins’s caricature of half the country is the sort of monocausal explanation that declines to take seriously the real forces that led to Trump’s rise: the economic dislocation brought about by automation and globalization; the collapse of the manufacturing sector; dueling opioid and suicide epidemics; a three-year consecutive decline in the life-expectancy rate; a crisis of loneliness and despair brought about by family collapse, institutional decay, and declining social capital; a student-debt crisis that has crippled young people’s futures; the corruption of our media and sense-making institutions; and a growing disconnect between our politically correct, chthonic governing elites and the concerns of ordinary Americans, which include such untouchable issues as immigration, the warfare state, and corporate bailouts. As Tucker Carlson puts it in his book Ship of Fools: “Happy countries don’t elect Donald Trump… desperate ones do.”

There is a growing intellectual movement on the Right (I call them the “New Right,” though they have also been called the “illiberal Right” and even “America’s Orbánists”) that understands this, even while acknowledging Trump’s many flaws. For some in this cadre, Trump is not unlike Hegel’s “world historical figure,” a leader who embodies the zeitgeist, if only for a moment, and carries forward the ruthless march of Kant’s “World Spirit,” discarding stale orthodoxies and outdated structures along the way. For others, Trump was merely a bull in a china shop who shattered the postwar consensus, brittle as it was, and summoned in its place a return of the “strong gods” (to borrow Rusty Reno’s phrase) of loyalty, solidarity, and home. The oracles of these strong gods are an impressively credentialed cast of scholars and writers; they include Notre Dame professor Patrick Deneen, former Trump advisor Michael Anton, New York Post opinion editor Sohrab Ahmari, Israeli political scientist Yoram Hazony, and Harvard Law professor Adrian Vermeule.

The New Right is not a monolithic entity, nor does it follow a set of prescribed tenets. It is, what George F. Will (of all people) might call, a “sensibility.” Certainly, there are uniting threads of nationalism, populism, protectionism, and traditionalism at play; yet what distinguishes the New Right more than anything is its counter-revolutionary spirit, its politics of opposition. “In this progressive theocracy in which all must worship at the altar of Wokeness,” writes Hillsdale professor David Azerrad, “conservatism, if one can still even call it that, is more about overthrowing than conserving.” If Atkins is right about anything, it is this: With Trump at the helm, conservatism has become less an ideology than a battle cry. Where the old guard stood athwart history yelling “Stop!” the new guard screams, in a pitch closer to that of Rousseau than Burke, “Tear it all down!” “This new Right,” says Azerrad, “has a decidedly unconservative temperament.”

Post-fusionism and the dead consensus

In some ways, conservatism has never been a fixed orthodoxy. Russell Kirk, the great cloistered sage of conservatism, famously characterized the tradition as “neither a religion, nor an ideology,” but “an attitude” possessing “no Holy Writ and no Das Kapital to provide dogmata.” Even the so-called consensus that animated postwar conservatism was not a coherent ideology, but the cobbling together of three disparate factions: the “three-legged stool” of the Reagan coalition—classical liberalism, social traditionalism, and muscular interventionism, all held together by the glue of anti-communism. The melding of these traditions became known as “fusionism,” a term associated with William F. Buckley, though it is said to have originated with National Review editor Frank Meyer. The New Right, for reasons that were not initially clear to me, defines itself as stridently post-liberal, and therefore “post-fusionist.”

I spoke with Patrick Deneen, author of Why Liberalism Failed (a book Barack Obama recommended for its “cogent insights into the loss of meaning and community that many in the West feel”). What was it, I asked him, that needed to be torn down? What conserved? “In the 1950s and the 1960s,” Deneen told me, “fusionism made a degree of sense, especially in light of the Cold War and the threat posed by communism… as well as a growing sense that the welfare state was undermining American prosperity. Now, in the aftermath of the Cold War, since 1989, that fusionism makes a lot less sense.” Actually, he continued, it was never really a genuine fusion in that the various parts never became one but remained in tension. Communism—which is premised on the idea that human beings are malleable and can overcome the natural bonds that tie them to home, country, and past—used social engineering and economic centralization to weaken the family. It promised the recovery of what Marx termed “species being,” an early prototype for what the Bolsheviks would later call the “New Soviet Man.” For these and other reasons, social traditionalists saw in liberal individualism a powerful weapon for combatting left-wing collectivism and defending institutions like religion and family. Since the fall of the Berlin Wall, however, new stresses have been exerted on the fusionist stool that not all of its legs were equipped to handle.

Liberalism may have been able to ward off the Left’s collectivist impulses for a time, Deneen and others maintain, but its own Randian excesses—its materialism and fetishization of autonomy—have had the effect of undermining the very structures conservatives say they want to protect: family, religion, community, and limited government. “Today our challenges are different,” wrote Sohrab Ahmari in October 2019, whose public joust with former National Review writer David French became an inflection point for the New Right. “Our society is fragmented, atomized, and morally disoriented. The new American Right seeks to address these crises—and to do so we need a politics of limits, not of individual autonomy and deregulation.” Indeed, borders, boundaries, and limits, along with a religiously reordered public square, are key to the cultural revival the New Right seeks to bring about. It is not surprising, then, that the row between Ahmari and French, which New York Times columnist Ross Douthat called “a full-employment bill for conservative pundits,” was ignited by a debate over whether public libraries should be permitted to stage Drag Queen Story Hour events for children.

I talked briefly with Ahmari, who declined to be interviewed but pointed me to what he described as his “most definitive statement” on these matters. The gist of that essay is that to defeat collectivism we must—all irony aside—implement collectivism. “The vast administrative state,” he writes, “arises in order to regulate societies that have been deregulated by an individualistic liberalism.” True freedom, he adds, requires a moral and religious teleology, not only at the private and cultural level, but at the level of the “state and the political community.” In March 2019, Ahmari and 14 others in the post-fusionist caucus outlined an alternative vision to what they call the “warmed-over Reaganism” of French and other beltway insiders. They argued that the old consensus “paid lip service to traditional values” but “failed to retard, much less reverse, the eclipse of permanent truths, family stability, [and] communal solidarity.” The Lockean tradition of limited government and the value-neutral public square—the postwar consensus—may have defeated communism and secured natural rights, but it has also displaced American workers, treating them as “interchangeable economic units” in a “borderless world.”

In discussions such as these, the New Right likes to cite journalist David Goodhart, whose book The Road to Somewhere makes a distinction between cosmopolitan “anywhere” voters and their more nationalist “somewhere” counterparts. For years, Deneen told me, our highly financialized consumerist economy has benefited this former group at the expense of the latter. Our elites have a mobile soul and the ability to thrive anywhere; they have achieved a kind of portable identity, Deneen argued at a recent public lecture. Their first-class educations have equipped them with the knowledge and skills to survive, and even profit from, the incessant mutations and revolutionary upheavals—what Joseph Schumpeter has called “creative destruction”—of an increasingly globalized technocratic capitalism. Then, of course, there are those who are not part of the educated ruling class—those who value home, stability, tradition, generational continuity, and memory, and “for whom relocation,” in the words of French demographer Christophe Guilluy, “is almost always a wrenching experience.” The current liberal order, Deneen insists, is failing these people and casting them aside as dead wood.

Several conservatives I chatted with, including Deneen, mocked National Review writer Kevin Williamson’s charge that the white working class “failed themselves,” that they need to get off OxyContin, rent a U-Haul, and go where the jobs are. “Isn’t that what America is about?” I asked Deneen. “Whatever happened to the pioneer spirit?” Deneen, who connected with me several times over Skype and is the paradigmatic Notre Dame professor (Irish and Catholic, with a friendly patrician demeanor), told me: “For the most part, the people who departed from their home countries came in order to settle, in order to make a home here. That’s as much a part of the American self-understanding as the idea of the pioneer or person who gets up and goes.” He then reminded me of characters like Dorothy from The Wizard of Oz, a girl who feels trapped by her boring life in dusty Kansas, but by the end of the film clings to the mantra “there’s no place like home.” Or George Bailey from It’s A Wonderful Life, a man who desperately wants to leave Bedford Falls but ends up becoming one of its foremost contributors. “These are some of the most mythic tellings of who we are,” Deneen said.

When I asked him if perhaps he and others weren’t reaching back to a bygone age, seeing America as “some kind of front-porch Republic that no longer exists” (I learned later that Deneen had actually founded a conservative journal called Front Porch Republic), he pushed back: “America’s civic life and the kind of nation that we’ve built over the course of our history has relied extensively on a large number of people who have dedicated themselves to improving the places where they have lived and settled. A lot of what we think about as the achievements of America,” he told me, “is not just the pioneers, but the people who have… improv[ed] the places where they are. And I think that ethos has been deeply undermined because of changes to the economic order of the United States.” At this point, I followed up with the words of philosopher C. Bradley Thompson, who has characterized Deneen’s vision of the country as being “like the Andy Griffith Show forever,” which is “not what America is all about.” Deneen’s response was succinct: “It’s odd to hear someone say that Mayberry is un-American.”

Deneen spoke passionately of the need for a strong middle class and of the various civic and national security reasons for retaining a robust manufacturing sector, citing the pandemic and our inability to produce the necessary personal protective equipment. For Hillsdale College professor David Azerrad, the question of economy also comes with significant cultural ramifications. “The issue is,” said Azerrad when we spoke, “do we have an economy that is producing well-paying jobs that allow men without degrees to find dignified employment so they can get married and raise a family? The issue is less location than the bifurcation of the economy into menial service jobs and abstract thinking jobs. That’s the issue,” he told me: “the fact that manly men are viewed as a problem and made to feel less and less at home in the American economy and society.” When I brought up Kevin Williamson’s point, Azerrad responded, “There has to be a backbone of the country that will work with its hands. If it means moving a few towns, that’s fine. But you can’t move to Mexico.”

Azerrad looked pained when I asked him to give his brand of conservatism a label. “I don’t know that I’m comfortable—I mean, if I had to give myself a label, I would say I am part of the New Right that is dissatisfied with the platitudes of what Rusty Reno has called ‘the rotting flesh of Reaganism.’ I want a Right that is anchored in the realities of the 21st century, that understands its base, that is aggressively fighting the culture wars, that is not beholden to the neocons on foreign policy or to the libertarians on economic thinking.” At one point in our conversation, he shared a line from one of his friends, whom he declined to name: “The Republicans should be the party of men who like being men, women who like being women, and Americans who like being Americans.” He flashed a boyish grin.

Orbán and the liberal “anti-culture”

Deneen spoke with me from his office. Behind him hung a portrait of Alexis de Tocqueville, a framed photograph of former President of Notre Dame Fr. Theodore Hesburgh, and an artsy world map that, while not strictly functional, conveys the impression that Deneen is a “global thinker.” Which, in fact, he is. Unlike many in his camp, who have struggled to articulate a forward-looking policy agenda, Deneen understands that opposition alone cannot sustain a political coalition. In his public debate with David French at Catholic University, for instance, Ahmari floundered when faced with French’s repeated questioning of what, precisely, he would do to reorder the public square. How, French wanted to know, would Ahmari bring about the “Highest Good” he wished to see, which would presumably involve banning men in drag from public libraries. “What public power would you use?” French asked. “And how would it be Constitutional?” Ahmari uncertainly suggested holding public hearings, applying cultural pressure, and passing local ordinances, but seemed otherwise at a loss.

Deneen, who wants to see the GOP become a working-class party, was at no such loss. His policy prescriptions included, among other things, rethinking the United States’ Europe-centered foreign policy; forging potential alliances in the near-East; establishing a “more contestatory role with China” while strengthening our relationship with India; introducing pro-family legislation like paid parental leave; taxing university endowments; and redirecting Federal support from liberal arts colleges and universities to job-training and apprenticeship programs. The way we do education in America results in the “overproduction of elites,” Deneen declared. “There need to be fewer people like me, with jobs like mine.” When I laughed at this, he smiled and said: “I mean, gosh! Just try getting someone to do brick work on your house.”

In November 2019, Deneen traveled to Budapest to visit Hungary’s Prime Minister Viktor Orbán, who admires Deneen’s work and has met with other like-minded conservatives in the past, including Rod Dreher and Yoram Hazony. Deneen sees Orbán’s approach as an example of “how a non-globalist, national-conservative direction could be developed” in America. Deneen told me:

The next working-class conservative administration should take a look at some things being done in nations such as Hungary—which I know is the bête noire of liberals—but their policy is showing signs of supporting family formation and reversing declining birth rates. They’ve been very aggressive and creative… One policy provides significant funds toward the purchase of a home, depending on the number of children that are born into a family. Families with three or more children are relieved of almost all income taxes. Their government provides generous child support and maternal leave benefits. These are really extraordinary kinds of policies, but I think unless there is a similar commitment by our citizenry, through the auspices of our government, we are likely to see the continued decline of birth-rates in our nation and the concomitant generational selfishness that you get when people no longer feel a… connection to the future.

It isn’t just Deneen. Many on the New Right have praised Orbán’s leadership, from Pat Buchanan to Christopher Caldwell to Sohrab Ahmari (who once claimed that “the highly literate Orbán has done a much better job of actually enacting a conservative-nationalist agenda than Trump has”).

This fascination with Hungary worries many of those on the Left and liberal Right who see Orbán as an authoritarian, or at least one in the making. And they have a point. Since coming to power in 2010 and declaring his state an “illiberal democracy,” Orbán has overseen rampant cronyism and done much to undermine his country’s democracy. Beyond diminishing the fairness and openness of elections in Hungary, the prime minister has curtailed press freedoms, had journalists arrested, and, through the Fidesz party and its allies, seized control of over 90 percent of its media outlets. Since the outbreak of the coronavirus, Orbán has only ramped up his autocratic tendencies, using the pandemic as an opportunity to suspend elections and centralize power, effectively ruling by decree.

For all that, attacking the New Right through Orbán, while rhetorically effective, offers a distorting lens at best. My conversation with Deneen made it clear that for traditionalist conservatives the allure of Orbán’s approach runs deeper than politics and boils down to the question of what the telos (purpose or function) of a society should be. “It’s a concept of society,” Deneen told me, “that is pre-liberal, that has at its basis the fundamental society, the family.” Whereas liberalism sees the individual as the fundamental organizing unit of society, traditional conservatism begins with the family. The family, after all, shapes and gives rise to the individual. I cut in: “So instead of stripping society down to atomized individuals in a ‘state of nature’ and then building up Lockean rights,” I asked Deneen clumsily, “you’re starting with the family, and then society grows out of that?”

“That’s exactly right,” Deneen told me. “It’s conceptually and anthropologically different from liberal assumptions. If you begin by building from that point and you think about the ways that those institutions are under threat from a variety of sources in modern society… to the extent that you can strengthen those institutions, you do the things that someone like David French wants, which is to track a lot of the attention away from the role of central government. One of the reasons liberalism has failed in the thing it claims to do—which is limiting central government—is precisely because it is so fundamentally individualistic that radically individuated selves end up needing and turning to central governments for support and assistance.”

According to Deneen, liberal orders seek to liberate individuals from the “despotism” of custom, place, and tradition, reducing culture to a sterile consumerism, allowing us to “sample from other cultures but not be of a culture.” This “anti-culture,” as he calls it, is at the heart of the liberal project, whose aim is to “free us” from the traditional associations and commitments that would bind us, limit us, and define us. Liberalism, then, is a fundamentally homogenizing force. By compelling us to affirm all cultures, it deprives us of our culture. By taking us everywhere, it leaves us nowhere. By urging us not to conform, it renders us formless. This formlessness is a hallmark of the liberal anti-culture. “In the same way that we have bankrupted the next generation by leaving them negative balances in their bank accounts, we’ve given them negative balances in their cultural coffers,” Deneen said.

In his recent book Return of the Strong Gods: Nationalism, Populism, and the Future of the West, Rusty Reno expands on this critique. His central thesis is that, since 1945, Western culture has been one of “anti-imperatives”—anti-fascism, anti-totalitarian, anti-imperialism, anti-colonialism, and anti-racism. These are what the author calls “weak gods.” “In the second half of the twentieth century,” he writes, “we came to regard the first half as a world historical eruption of the evils inherent in the Western tradition, which can be corrected only by the relentless pursuit of openness, disenchantment, and weakening.” Traumatized by the horrors of fascism and totalitarianism, and by the violence of two world wars, the postwar consensus was a repudiation of the powerful passions and loyalties that unite societies and bind men to their homelands. Anything strong or solid became suspect. Globalism supplanted nationalism, the “open society” upended traditionalism, relativism questioned axiomatic truths, multiculturalism replaced cohesion and solidarity, and critique and deconstruction chipped away at the pillars of Western civilization.

But citizens, Reno argues, will not tolerate a society of “pure negation” for long. The strong gods always return. Public life requires a shared mythos and a higher vision of the common good—what Richard Weaver called a “metaphysical dream.” Human beings long to coalesce around shared loves and loyalties. We unite in solidarity to elevate the sacred. “Our social consensus,” Reno writes, “always reaches for transcendent legitimacy.” There must be a center of things. Without that integrating ideal, without that centripetal force, societies begin to disperse, spiraling ever outward in a “widening gyre” until the culture lies in fragments. “There can be no society,” wrote the French sociologist Émile Durkheim, “which does not feel the need of upholding and reaffirming at regular intervals the collective sentiments and ideas which make its unity and personality.”

The strong gods, in other words, will always be with us. The only question is, what form will we allow them to take? And how will we prevent them from overpowering us once we summon them?

Taking the New Right seriously

Like others in my intellectual bubble, I was not truly aware of the scale and intensity of the Trump phenomenon, nor of the rising populist fervor throughout the West, until a few months prior to the 2016 election. It was around September—when Michael Anton, using the pseudonym Publius Decius Mus, wrote a scathing essay for the Claremont Review of Books entitled “The Flight 93 Election,” in which he urged his readers to take a chance on Trump. “2016 is the Flight 93 election,” he announced: “charge the cockpit or you die.” The essay made the rounds and soon became the basis of a cottage industry for legacy media pundits. Anton lambasts the liberal international order (the “Davos class”) and establishment conservatives (“keepers of the status quo”) for constantly failing up and leaving Americans worse off by just about every dimension in the process. The piece is over-the-top, and it reads like a list of war crimes, but there was also something bracing about it that captured the energy and frustration that many on the Right, eager for a change, were feeling in 2016.

I remember thinking at the time that this new nationalist populism, whatever it was, had a lot to say about the “ills” plaguing the nation, but almost nothing to speak of in the way of viable remedies. In the months and years that followed Trump’s election, I read books like Charles Murray’s Coming Apart, Patrick Deneen’s Why Liberalism Failed, Oren Cass’s The Once and Future Worker, and Michael Lind’s The New Class War. I was discovering that underneath the noise and hysteria, underneath the media’s condescension and lies, underneath Trump’s bloviating and his tweets, underneath the angry chants of “Lock Her Up!”—there were not only dire concerns hitherto ignored by both political parties, but there was also something like a serious, solutions-oriented intellectual doctrine that, however unconstrained (and, in my view, misguided), was emerging to grapple with those concerns. As a libertarian, I had never even bothered to notice.

Which brings us to the 2020 election. Though pollsters forecasted a sweeping wave of Democratic victories down-ballot, the GOP is on track to control the Senate, despite being massively out-raised. In the House, while Democrats retained control of the lower chamber, the GOP made impressive gains, flipping 12 seats and ushering in a record number of Republican women. Trump himself earned an unexpected share of the minority vote, according to exit poll data. The jubilation that flooded the streets following Biden’s victory was fleeting, giving way in short order to confusion and in-fighting as Democratic officials and lawmakers struggled to process the underperformance. As votes were still being counted, the headlines began to pour in: “The 2020 Election Has Brought Progressives to the Brink of Catastrophe,” moaned Eric Levitz at New York Magazine. “Trump lost, but Trumpism did not,” wrote Michael Tackett at the Associated Press. “Trumpism has been vindicated,” declared Eric Zorn at the Chicago Tribune. “‘It was a failure,’” announced Christal Hayes at USA Today. The New Right, in other words, has an opening.

I asked the Dispatch editor-in-chief Jonah Goldberg if the New Right can exploit it. Goldberg, who has been a staunch critic of Trump, is skeptical that the GOP could or should become a so-called “working class party.” He told me: “I think emphasizing class isn’t as bad as emphasizing race, but I don’t think either are particularly helpful forms of reducing politics to a single issue. I’m against monism in all its forms. I don’t like to reduce any complex phenomenon to a single cause. And I don’t think the Republican party should be reduced to a single focus on class issues.” Goldberg criticized the idea, peddled by politicians like Marco Rubio, Tom Cotton, and Josh Hawley, that Trump’s victory in 2016 and his gains in the last election were due to a surge of working class energy. “I think that’s really dumb analysis… [T]hey’re getting the causality backwards. These people didn’t join the Republican Party for its working-class policies because virtually all of Trump’s successes were variations of outsourcing to the Federalist Society and Paul Ryan. These things people are calling zombie Reaganism were… the successful parts of his presidency.”

For Goldberg, the intellectual conservatism being pushed by outlets like the Claremont Review of Books and First Things has little to do with the Trump phenomenon. Deneen and Ahmari can talk about bringing back manufacturing and banning drag queens from local libraries but, Goldberg told me, “it misses the point that Trump’s attraction was as an entertainer, a celebrity, and a fighter. I mean, yeah, they might be pro-life, but the GOP probably had them already. They might be against some of the crazier progressive stuff like defunding the police, but the GOP had them already.” To the extent that Trump’s presidency was effective, his success came from a combination of satisfying traditional Republicans on policy and then ginning up the tribal passions of a whole new segment of the population that may have otherwise been inclined to vote Democrat.

When I asked him whether he thought it was possible to keep Trumpism without Trump, Goldberg wasn’t having it. Doubling down on policy prescriptions that Trump himself never championed and hoping this will be a “satisfactory substitute for the folks who just like the pro-wrestling aspect of the Trump presidency? I don’t think they can sell it,” he told me. The idea that “anybody who goes all in at a MAGA rally, and is just in it for the spectacle—what they call in pro-wrestling ‘Kayfabe’—is going to sit through a Mike Pence rally while he explains the details of his new tax credit is deluded. It’s like when Homer Simpson is watching Lake Wobegon and he starts kicking at the TV saying, ‘Stupid TV! Be more funny!’ I just don’t see how these guys can fill the entertainment criteria with turgid policy proposals.”

But what about the underlying concerns that led to Trump’s election? I asked. Aren’t folks like Deneen at least trying to address real problems that ordinary Americans face? Goldberg, who said that he likes and respects Deneen, went on: “I have very few problems with the symptoms. When he says loneliness is a problem, I agree. When he says alienation is a problem, I agree… I think all of these guys have got to do an enormous amount of work in persuading me that they have solutions that will actually fix the problems that they’re talking about rather than just replace the current class of policymakers with a new crop of policymakers who will reward their constituents the way they want to be rewarded. When Hayek said in the Road to Serfdom that it was dedicated to socialists in all parties, this is part of what he was getting at.”