Culture Wars

On Activist Scholarship: An Interview with Helen Pluckrose

The universities are also where rigorous research, science, and valuable knowledge production continues to happen, and it is the universities we will need to push back at this and self-correct.

In recent years, free speech and inquiry have come under attack on college campuses, ethical relativism has spread, and demands to decolonize syllabi and rid them of canonical white male texts and thinkers have become increasingly common. Hostility to reason, objectivity, and Enlightenment universalism now disfigures some social science and humanities departments, and these alarming ideological trends have trickled down into mainstream culture where they affect the lives of ordinary people.

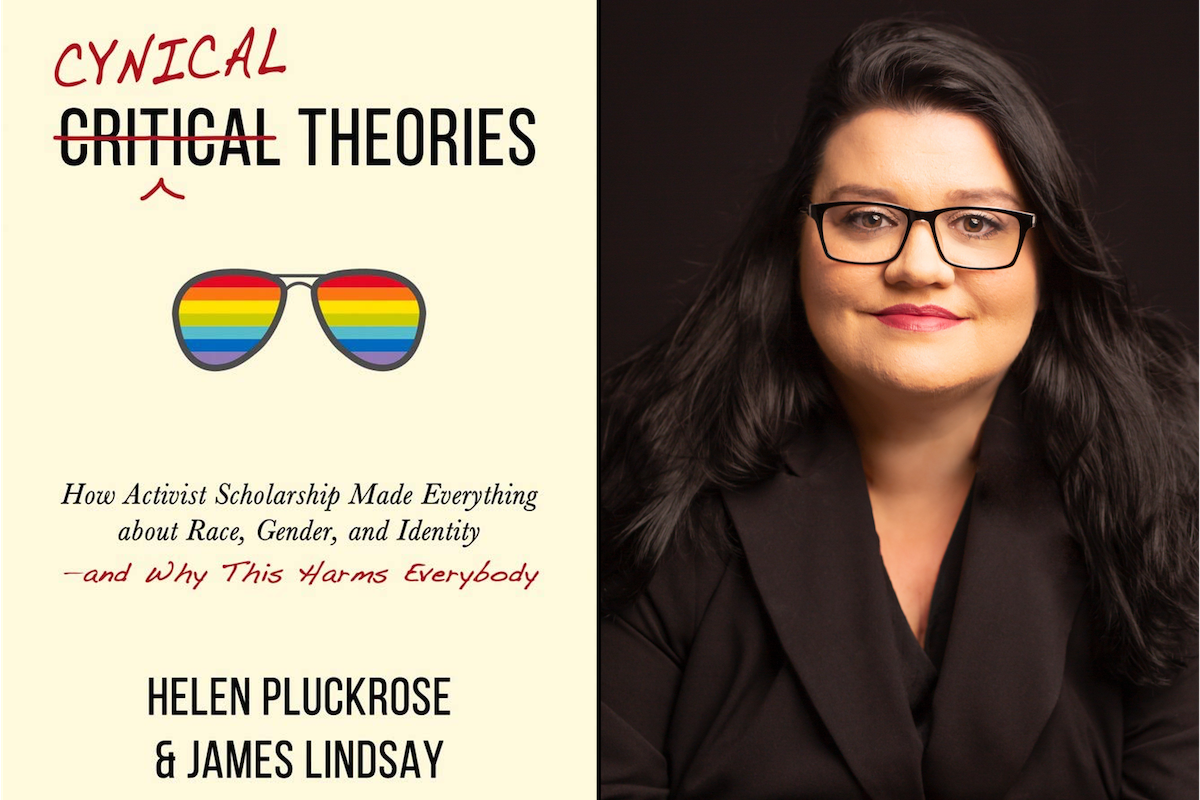

In their book, Cynical Theories: How Activist Scholarship Made Everything about Race, Gender, and Identity—and Why This Harms Everybody, Helen Pluckrose and James A. Lindsay look at how postmodern theory and activism have come to replace traditional scholarship, and the threats these anti-Enlightenment beliefs pose to liberal democracy. I caught up with Pluckrose, an essayist and editor of Areo magazine to discuss her book. She lives in England.

Jason D. Hill: Helen, Thanks for speaking to me and congratulations on the huge success of the book. The book covers a lot of territory from postcolonial studies, to critical race theory, fat studies and disability studies, queer theory, feminism and gender studies and, of course the philosophical rubric that ties them all together: postmodernism: First, can you tell our readers Why you and James Lindsay decided to write this book now? Postmodernism has been around in our universities for a long time. Why the sudden urgency?

Pluckrose: It may feel as though the opposition to postmodern thought is new, but in fact the Marxists have been opposing it from the beginning—see, in particular Noam Chomsky and Jürgen Habermas—and the scientists, empiricists, and liberals from at least the 90s—see Alan Sokal, Meera Nanda and Martha Nussbaum. The reason the pushback is suddenly so much more evident to people outside the universities is because the current manifestation of postmodern ideas of power, knowledge, and language is Critical Social Justice (CSJ) scholarship and activism. CSJ’s influence has increasingly been being felt much more broadly than just in the universities. Books like Kendi’s How to be an Antiracist and DiAngelo’s White Fragility are best sellers. People are being no-platformed, fired, and cancelled for disagreeing with these ideas. Here in the UK, the police have investigated somebody posting a limerick on Twitter that did not adhere to trans activism’s concept of gender identity and a journalist publishing an interview with a historian who said slavery was not genocide. Gender critical feminists are routinely threatened and intimidated for making arguments that self-ID is a threat to women’s sex-based rights. Since the brutal death of George Floyd and the BLM protests, my colleagues and I have been inundated by requests for assistance from individuals whose employer, university or children’s school is trying to impose mandatory “antiracist” training of a thoroughly illiberal kind rooted in critical race theory ideas about invisible systems of whiteness underlain by bad science about “implicit bias.” We have had to set up a Discord server to try to triage this and help people convince their employers to allow them to reject racism from their own philosophical, ethical or religious beliefs and not this highly theoretical and political one. It is important to note that people of all races object to this kind of “antiracist” training and that black people are politically and intellectually diverse. Similarly, many women reject intersectional concepts of feminism, few LGBT people have even read queer theory, the majority of trans people just want to be left alone to live as feels authentic and most obese and disabled people have no wish to take this aspect of themselves on as a political identity.

Hill: Define for our readers the four or so basic tenets of postmodernism and why having spawned so many disciplinary satellites you regard it as the danger that it is?

Pluckrose: The postmodern ideas that have survived into the successive waves of “theory” culminating in Critical Social Justice are rooted in an understanding of knowledge as a product of power perpetuated by discourses. That is, objective knowledge is inaccessible and what we consider knowledge is actually just a cultural construct that operates in the service of power. Dominant groups in society—wealthy, white, heterosexual, western men—get to decide what is and isn’t legitimate knowledge and this becomes dominant discourses which are then accepted by the general population who perpetuate oppressive power dynamics like white supremacy, patriarchy, imperialism, heteronormativity, cisnormativity, ableism, and fatphobia. The critical theorists exist to deconstruct these discourses and make their oppressive nature visible. This results in the breakdown of boundaries and categories through which we understand things like emotion and reason, fact and fiction, male and female. It also produces a profound cultural relativism and a neurotic focus on language and language policing as well as a rejection of individuality and humanism in favor of identity politics. This is a problem because of the resulting threats to freedom of belief and speech, the divisive tribalism and the rejection of science, reason and liberalism.

Hill: From my reading of the book, I came away thinking that postcolonialism was the social justice activist form of activist scholarship that was most dangerous in its comprehensive attack on the West. Do you agree with this assessment?

Pluckrose: I am always wary of speaking in terms of attacks on the “West” because postmodernism, CSJ and the kind of postcolonial and decolonial theory that forms part of it is very much a Western phenomenon. It doesn’t really have much of a presence anywhere else yet. Meanwhile, the antidote to it—science, reason, and liberalism—are values held by people everywhere. However, it is fair to say that postcolonial theory and postmodernism generally demonizes the West as a colonial, white supremacist, capitalist dystopia. Its greatest threat is to science and rigorous empirical research and its problematization of all historical figures and drive to “decolonize” knowledge.

Hill: You write that you do not intend to attack the universities at all. Let me push you on this a bit. The universities are the domains in which these attacks against Enlightenment values and modernity are occurring. It’s university administrators and bureaucrats who are often the creators of these social justice theory disciplines. I know, for example, the mass notification received by faculty at my institution to “Decolonize that Syllabus,” came from a very level administrative command post—not from faculty. So, given the complicitous nature of the universities in the creation of these disciplinary sites, why should we not, say, defund certain aspects of the humanities and social sciences where the professoriate are not teaching critical thinking skills, demonizing reason and logic, and now declaring English a virtual outlaw language?

Pluckrose: The universities are also where rigorous research, science, and valuable knowledge production continues to happen, and it is the universities we will need to push back at this and self-correct.I cannot support aims to defund specific disciplines because I do not think we want to set a precedent of governments deciding what is and isn’t valid knowledge. We need to beat this on the level of ideas and make these ones die a natural death.

Hill: Is there hope in the academy for a renaissance? Will reason, logic, rational discourse, and a commitment to universal liberal values prevail? Or have things turned an irreversible corner? Are these activist scholars and their work national security threats?

Pluckrose: I hope so, yes. That is certainly what I am working for. If we take a long look at the history of universities, we see that they have produced terrible ideas before and they have self-corrected before. We need to change culture and the universities will change. There are many organizations already working for this including FIRE and Heterodox Academy. However, I do think we should not underestimate the current threat. I don’t think it would be going too far to say that what we are witnessing right now is an attempted cultural revolution. I don’t think it can win in the long term because it is too irrational and self-contradictory and results in circular firing squads. The big question is what will push it back? My fear is that it will be a populist, anti-intellectual, anti-equality movement from the Right and that this would be just as illiberal as Critical Social Justice and could actually roll back advances made for racial, gender, and LGBT equality.

Hill: Finally, what keeps you going? What gives you hope in this world to just keep fighting for the values you so clearly articulate in your brilliantly written book?

Pluckrose: The amount of hope I have varies considerably day by day, but I keep going because I think liberalism, humanism, science, and reason really matter and it seems so obvious to me that these are what we need to value as a society. I actually seem to be incapable of not arguing for them because I am a very opinionated person although my targets change. It amuses me that I am currently accused of being far-right by social justice types because, before I criticized CSJ, I focused on religious irrationalism and illiberalism and then I was accused of being far-left because I focused most on Christianity. However, I became far-right as soon as I extended the same criticisms to Islam. I’m not sure why a consistent commitment to liberalism and evidence-based epistemology is so difficult for people to recognize. I don’t claim to be entirely unbiased, though. While I can and do respect ethical conservatives, who support liberal aims of freedom, individualism and universalism, I am of the Left and it is the Left I want to fix.

Thank you for your kind words about my book!

Hill: It has been my pleasure. I learned a lot from you, and so much of what I read was a confirmation of what I had also experienced in academia. I have spent the last 20 years warning readers about the dark side of what I had called Identity Studies.