Art

The Troubled Maker: Transgressive Art, Public Shame, and Mike Tyson

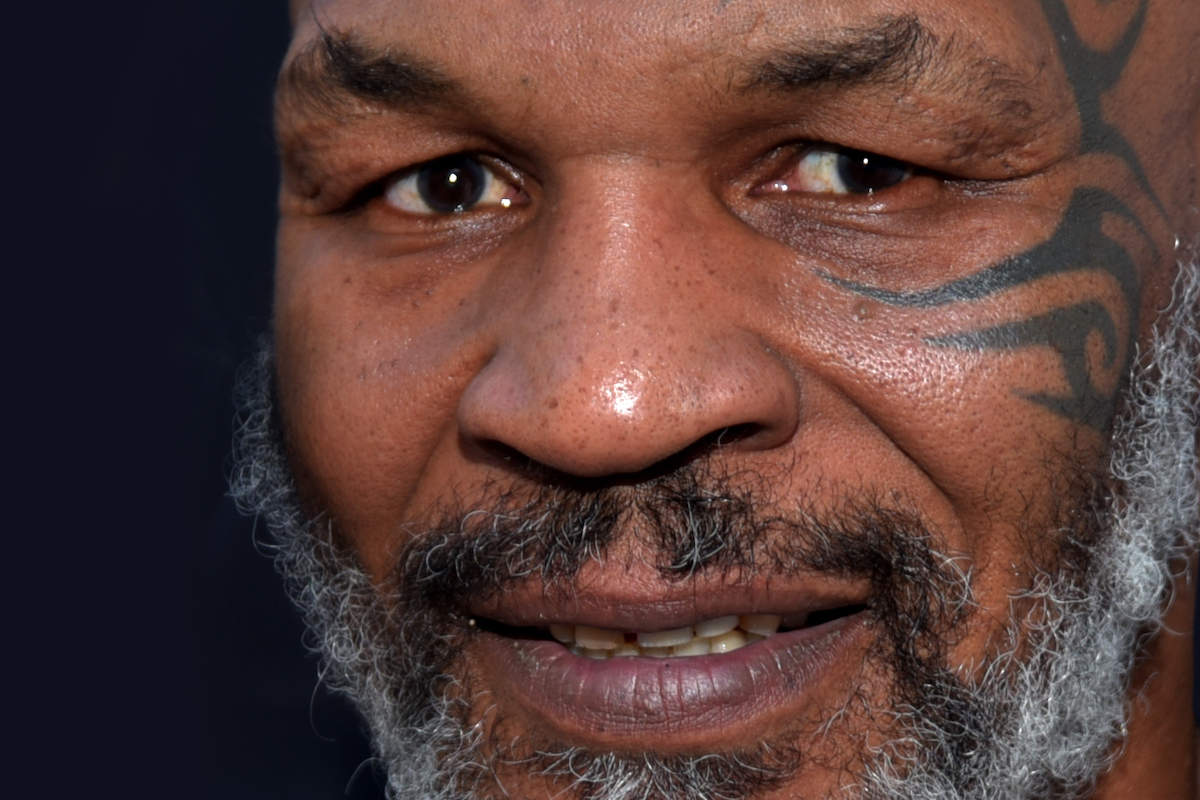

Tyson embodies the moral ambiguity of boxing’s rich tapestry: brutal and beautiful; entertaining and repellent; dishonorable and inspiring.

In many ways, my personal experience with life after public shaming has gone exactly as one might expect: depressing, painful, and weird. Yet, at some point over the past three years, after managing the existential crisis of fractured identity, and learning to refrain from scratching at the phantom limb of my reputation, I’ve noticed something strangely liberating about it too. I no longer struggle to reconcile my blue-collar background with my former aspirations of being a successful and cool artist; I no longer find it necessary to cultivate the avant-garde persona of an active performance artist and theatre director. Instead of worrying about every detail of ignominy, I can finally indulge in vulgar interests like Monday Night Football, Bo Jackson YouTube compilations, or Mike Tyson’s latest exhibition bout against fellow boxing legend Roy Jones Jr.

I didn’t even watch the fight, to be honest. I didn’t need to. At this point in his career, I’m more interested in Tyson’s redemption narrative than what remains of his athletic prowess. So I tuned in just in time to catch the post-fight press conference. There was a warmth and gentleness to the event—the rapport between Tyson and the room full of reporters was like a fireside holiday party among old friends. It was mutually respectful, everyone was jovial—simpering even—and drunk on nostalgia. “That was a hell of a question!” Tyson commended one reporter. “Thank you so kindly.” There were laughs as Tyson joked about smoking weed right before the fight, there were instances of genuine concern for Tyson’s health, and there were even some introspective philosophical moments that have become the norm from the cozy post-retirement pop-culture version that Tyson has slipped into: “What happens when I die? I may begin to live when I die… it has to be beautiful. It can’t be bad, dying has to be something special.”

When the press conference ended, Tyson softly thanked everyone—“It was really my pleasure, thank you”—before leaving to an unusual smattering of applause from the press corps. Lest we get too sentimental about this apparently reformed, grandfatherly iteration of Mike Tyson, here’s a quick look back at some of the previous encounters between the media and “The Baddest Man on the Planet”:

“I ain’t doing shit, scumbag. Fuck you.” [1996]

“Fuck off!” [1999]

“I wish one of you guys had children so I could kick them in their fucking head or stomp on their testicles so you could feel my pain.” [2002]

“I’ll eat your asshole alive, you bitch. You’re not man enough to fuck with me, you can’t last two minutes in my world… I’ll fuck you till you love me, faggot.” [2002]

Tyson embodies the moral ambiguity of boxing’s rich tapestry: brutal and beautiful; entertaining and repellent; dishonorable and inspiring. His 54 years have been a sold-out rollercoaster ride of self-destruction and salvation, as his struggle between being a role model and “a bad boy for life” has been a lifelong reality show.

I haven’t missed a phase of this man’s life; I grew up in awe of his mystery and superhuman athleticism, and remained transfixed during his fall(s) from grace. And as I watched him hold court at this congenial press conference, I saw in him all at once everything he’s ever been: an unstoppable force with an aura of invincibility, an ex-convict who was arrested 38 times before he turned 13, a victim of exploitation by those closest to him, a beast who once bit off part of an opponent’s ear, and an introspective and deeply complicated human being striving for redemption. Beyond even the uniqueness of Tyson himself, there is something else that strikes me as profoundly strange about Tyson’s second act—the vanishingly rare public display of moral complexity.

How does a controversial figure like Tyson exist in today’s post-#MeToo, pro-cancelation environment? He’s an unlikely anachronism against a backdrop of cultural revolution, a blitz of reckoning, with fervent erasure at the vanguard and crossed fingers at the rear hoping that what is removed will be replaced with something better. Our moment, we are told, is one of correction, in which statues are toppled, classic texts redacted, brand and sports logos retired, individuals paraded and condemned. This is our culture cleaning up. In many instances, it’s long overdue, in many ways it’s necessary, but it’s also attended by strains of unchecked hyper-negation that confuses sanitization with justice. In this progress towards a better functioning of society, how much excess of collateral cleansing may be expected? When does over-policing of “problematic” behavior bleach some of the important-yet-profane bacteria in the cultural ecosystem? Under an un-rehabilitative, scorched-earth cultural policy, moral ambiguity has no value, and any challenge to the burgeoning new status quo is quickly cast as fascist, racist, demonic. The result is an aimless and general referendum on wickedness.

Now that forgiveness has become a greater effrontery than sin, it’s likely that we would not have heard from Tyson again had his rape conviction occurred last year. No radio show, no movie cameos, no comebacks, no second (or is it third? fourth?) chance. And yet, Tyson can still draw attention and even elicit affection, as evidenced by the $1.2 million pay-per-view haul, which far exceeded expectations. Perhaps he hasn’t gone the way of Louis C.K., Woody Allen, or [insert any number of disgraced/erased men], because, 25 years removed from his prison stretch, he can plausibly leverage himself as a reformed man, or at the very least, a rehabilitation-always-in-progress project. Or maybe he benefits from people not taking him seriously anymore. More likely, he survived cancellation because fighters enjoy immunity because the boxing industry makes no pretense of elevated moral standards, unlike the civilized world of art and letters. This is the world in which I exist. Or at least, it’s the world in which I used to exist before I was called out in 2017.

I’m not as beloved as Mike Tyson, the convicted rapist, admitted batterer of women, professional puncher of faces, and notorious biter of ears. What a crazy thought. As he continues to pull in millions, and boxes his way to senior citizenship (and, honestly, good for him), my nascent career as an artist and theatre director lies in ruins following a social media campaign orchestrated by a former lover. The indiscretions of which I was initially accused amounted to little more than the wages of a messy love life, exacerbated by my own relationship failings, but not entirely without assistance from those in the relationships with me. I was secretly dating two women at once, I lied a whole fucking lot, and slept around too much, including—to the virtuous disgust of many—with a woman aged 22 (I was 37).

There were no crimes, no threats, no violence or legal proceedings, just unsupported allegations of an “abusive relationship” tossed around on social media and accusations that I had sent my ex “harassing emails” for months after we broke up. From there, the pile-on began. A crowd of avatars—most of whom I barely knew, intimately or otherwise—grew giddy on what anthropologist Roger Lancaster in his book Sex Panic and the Punitive State calls “poisoned solidarity.” Surreal claims emerged that I’d been involved in conspiracies of embezzlement and arson, and that I’d been maliciously spreading STDs (I’ve never even had an STD).

I made my apologies where appropriate, but apologizing wasn’t enough; I was expected to simply absorb the shame in some novel public ritual. The snowballing mob of aggrieved parties and organized allies pressured my employer into firing me, they convinced organizers to cancel my shows, and they cut off enough social support that it became impossible for me to stay in town. Many distanced themselves from me lest they be blackened by association, not because they believed there was any truth to any of the increasingly lurid claims.

The details can be found here, for those interested—all names have been altered. But the upshot was that I was left a pariah to the communities that used to be an integral part of my life and identity. None of this is to say that I was merely an innocent victim. I was—and still am—a difficult person. I’ve let unresolved childhood stuff sabotage several relationships, and I had a difficult time shedding the “bad boy” persona before it settled into the altogether less appealing “bad man” persona. It’s hard to rally sympathy for the consequences of a reckless life, but the extent of my public shaming was straight up bizarre. Like a human whack-a-mole game, I continue to get anonymous emails sent to publishers and collaborators any time I attempt to return to creative work.

I envy someone like Mike Tyson, who got to serve an actual sentence for his guilty verdict. People in my position hang suspended in perpetual fault, with no clear path to redemption. Guilty without terms, without sentencing, it can feel like a death penalty for everything but the body. In her book Conflict is Not Abuse (my life preserver during the lowest points), Sarah Schulman recognizes the use of “unidirectional” messaging for cutting off avenues of defense, mediation, or dialogue as a sublimation of traumatized logic into supremacy logic: “Refusing to speak to someone without terms for repair is a strange, childish act of destruction in which nothing can be won.”

Despite constant feelings of alienation, I know I’m far from alone. It seems like every day there’s another small press, writer, artist, venue, or musician getting called out for a range of wrongdoing, often petty, often waged without allowing dialogue an opportunity to resolve the issues offline. Not all cases are the same—some are perhaps more deserving of a demand for accountability than others, but enthusiasm for persecution idles high in the arts, manufacturing a consensus that those considered “bad people” should not be free to make art. This, despite the fact that the arts have long been a haven for misfits, troublemakers, weirdos, and anti-social outcasts of all kinds. During the culture wars of the 1990s, controversial artists like Robert Mapplethorpe and Karen Finley provoked hysterical conservative efforts to curb federal arts funding. But today, it’s the artists themselves who are the zealous guardians of decency, and in the process of purging those deemed enemies of progress, some very important art gets caught in the widening net of the “super-problematic.”

One of the more uncomfortable but unremarked-upon realities in this march of progressive punishment is that it often finds itself tangled in basic class issues. For all the talk about empowering the historically powerless, the moral codes are still largely authored by privileged actors and written in the language of wish-fulfilment. The poor are not cancelling anyone or anything. It’s worth emphasizing how pronounced class dynamics are in contemporary art scenes, likely a result of academia’s influence on the arts. I can’t help but feel that class and difference played a major role in my situation. My bad behavior and strained personal relationships alone did not lead to my disgrace, but I feel certain that my failure to fit in politically or in social status (which was reflected in my artwork as well) also had much to do with it. For dirtbag artists, access is primarily administered by the graduates of expensive art schools.

It has become fashionable to question whether cancel culture even exists, because—or so the argument goes—it’s not a real thing as long as someone like Mike Tyson is still making money. But this is the wrong debate to be having. What about those who aren’t powerful in the first place? Call it whatever you want, but it’s unfortunate that the debate about cancel culture has been straw-manned to focus on those “too big to be canceled” instead of those too small to fight back, especially when their exile is unwarranted or baseless. Those stories disappear after the point of scandal, too inconsequential to care about. When destroying someone can be done with such ease—without the need for dialogue or due-process—that is power too.

But I’m curious—hopeful even—that things may change in a post-Trump America. It’s no surprise that the censorious radical politics of rage reached a boiling point under Trump. His ability to bob and weave around every scandal (including more than two dozen accusations of sexual misconduct) and emerge unscathed created a crisis of tolerance on the Left. It’s a helpless feeling, and sometimes when you can’t thwart the poster-boy for the patriarchy you’re trying to dismantle, your co-worker, teacher, or your ex will have to do.

Cultural critic Adam Lehrer wonders if a changed landscape may emerge from “heterodox art.” In a piece for Caesura magazine, he suggests that “[T]here might be an opposition forming. Cancellation is, from one perspective, a kind of freedom. Once cancelled, you are unburdened of meeting the expectations placed upon you by the tragically conformist masses.” This would spring from an unwillingness to give power over to negative group consensus-making, thus deflating the stigma of “canceled” status. It reminds me of the chapter in Jon Ronson’s So You’ve Been Publicly Shamed about former president of the Fédération Internationale de l’Automobile, Max Mosley: He survived a public sex scandal because, as Ronson puts it, “he refused to be shamed.”

Imagine it—a critical formation of cultural outcasts; a bull market on cancel chic. A flipping of the cancel culture script that embraces the complexity and messiness of human life would be an antidote for our hyper-allergic cultural universe. It could be an opportunity for the surplus of the shamed circa 2016–2020 to restore both self and cultural value in a wonderland of error, imperfection, and troublemaking. I’m not suggesting that actual criminals, racists, misogynists should be let off the hook (although restorative justice could use some time trending on Twitter too); this is about the complexity that gets unreasonably—and, yes, at times unjustly—swept up in culture wars that admit only a stark division between good and evil.

Sure, I have a clear bias in welcoming the fantasy of a canceled cancel culture, but this goes beyond my own self-interest. This isn’t a cause I’ve adopted in order to defend myself. I have always believed that a healthy dose of transgression is good for keeping institutions on their toes, challenging the status quo, and fucking with the establishment; that misbehavior can be a critical component of art and culture. And I’ve always recognized the richness in the narratives of imperfect heroes like Mike Tyson, who can’t change his past, but can learn to find peace within his own contradictions: “I’m many things: I’m a convicted rapist, I’m a hellraiser, I’m a father, a loving father.”

At this stage of his career, Tyson is more self-aware than ever, presenting himself more as a trickster than a warrior, less angry and more thoughtful. However it came to pass, I’m glad that he was able to arrive at this point, no matter how ugly and uncomfortable that path sometimes was, and that we were able to watch, learn, and maybe, to some degree, even relate. It’s the dissenting and nonconformist works of art (and I use that term broadly to include personal narratives like Tyson’s) that are best positioned to oppose spikes in reductive bourgeois moralism, and are therefore more threatened by it. Whether there exists the possibility of deeper dialogue surrounding that which offends, or whether it faces increasing scrutiny to be canned or spooked into silence, remains to be seen.

In the meantime, maybe I’ll take up boxing.