Canada

On Remembrance Day, Celebrating Two Canadian Prisoners Who Took Down an Entire Shipyard

The need for secrecy was therefore paramount. But as he began to plot his sabotage, Clark realized he’d need at least one trusted accomplice.

To compensate for Japan’s manpower shortage during World War II, the country’s military commanders often shipped their prisoners to the Japanese mainland, where they worked as slave labourers in mining and heavy industry.

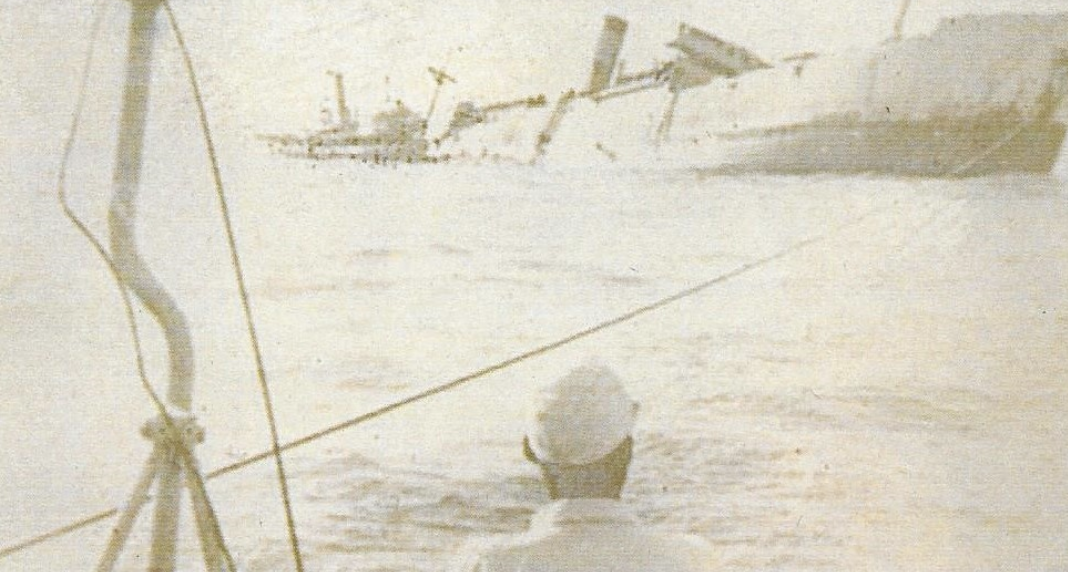

As someone who made such a trip after my own capture in 1941, I can attest that the journey to Japan was terrifying in and of itself. Because the Japanese didn’t mark prisoner transport ships with a red cross or some other agreed-upon symbol, thousands of prisoners were lost at sea when unsuspecting American submarines mistakenly torpedoed some of these transports. One such ship, the Lisbon Maru, carrying about 1,800 British POWs from Hong Kong to Japan, was sunk in the South China Sea on October 1st, 1942, by the American submarine USS Grouper, whose captain had no idea of the precious cargo in the hold. Eight hundred and forty-six prisoners died, either by drowning, or were shot by the Japanese as they tried to swim clear of the wreck.

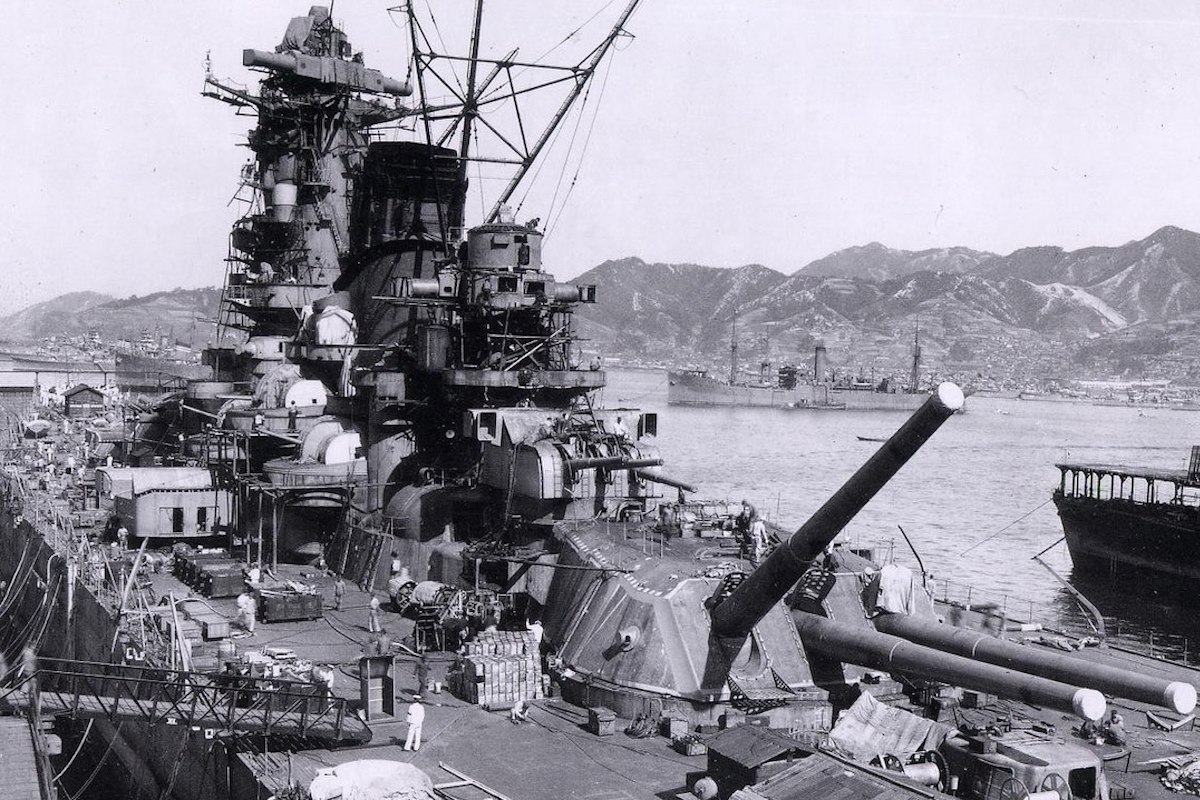

This was the backdrop when the first group of 1,180 Allied prisoners—including 663 Canadians, of which I was one—left Hong Kong on January 19th, 1943 on the unmarked Japanese transport steamer Tatsuta Maru. Prisoners were jammed into a section of the hold so tightly that we could lie down only in shifts. Toilet facilities consisted of large buckets lowered from above. The four-day trip was made particularly hellish by a dysentery epidemic that broke out. And when we arrived in Japan, we were dehydrated, half-starved, and covered with filth. Our destination, we were told, was the (then newly established) Tokyo 3D Tsurumi Prisoner of War Camp, at the Nippon Kokan industrial facility in Yokohama, then the country’s biggest shipbuilding works. (The camp went by several different names over the course of the war.) After leaving the ship, we were taken by train to our camp, which was about a mile from the shipyards. A day or two later, we began work—a schedule of 13 days on followed by one day off.

The Nippon Kokan yard was huge. It produced both civilian ships and naval vessels for the Imperial Navy, this at a time when Japan’s ships were being regularly sunk by American submarines. It surprised us all how little damage this vital facility had suffered, despite numerous attacks by American bombers. And one of my fellow Canadian POWs—Staff Sergeant Charles Alfred (“Charlie”) Clark, who’d served in the Headquarters unit of “C” Force at Hong Kong before becoming a Japanese prisoner—began getting the idea that humble prisoners might succeed where fleets of bombers had not.

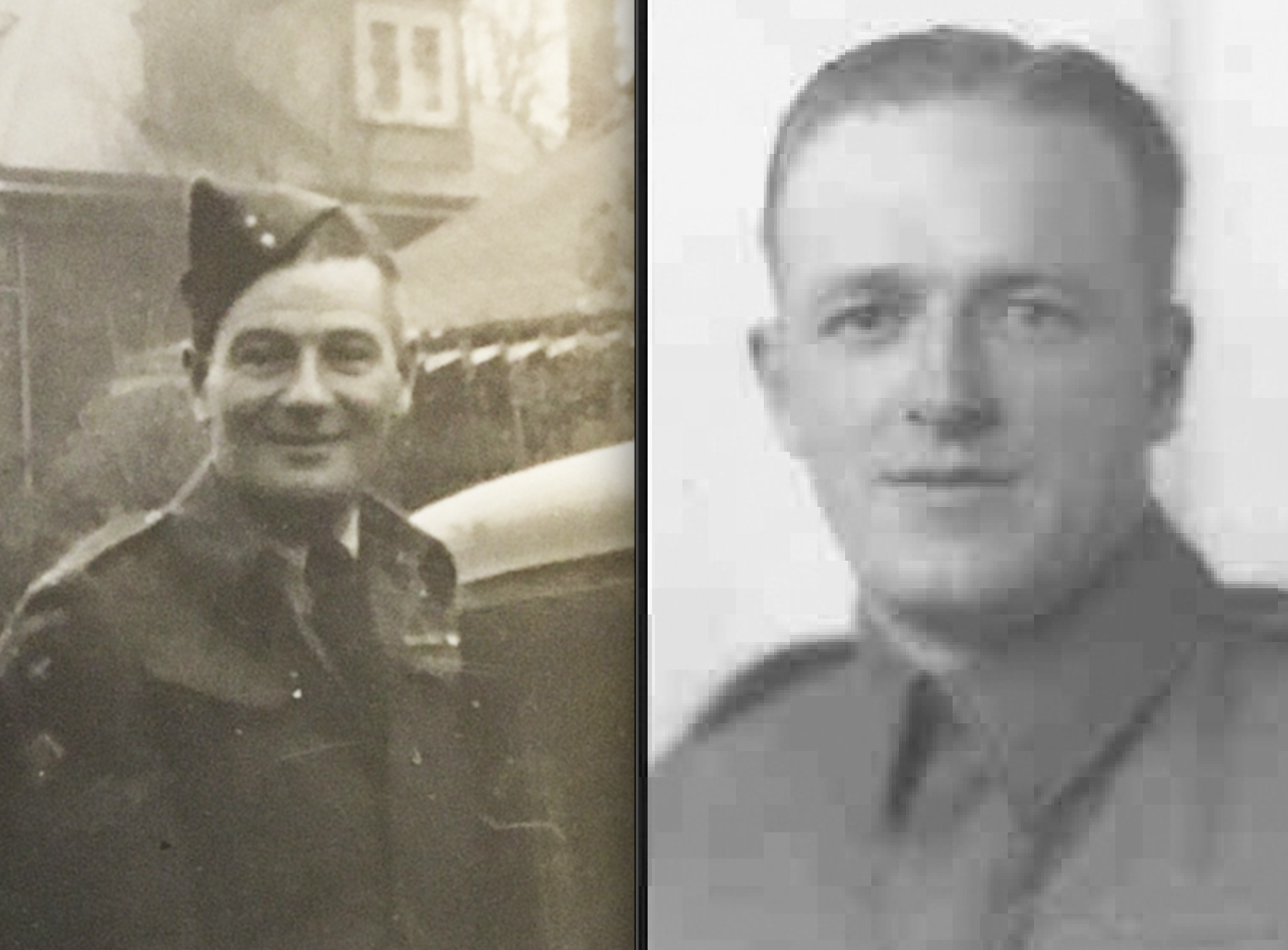

Clark was an unusual individual, one of the few soldiers who served in both World Wars. Born in England, Clark emigrated to Canada in 1915, whereupon he enlisted in the army and was wounded at Vimy Ridge. Following two decades of civilian life with Canada’s postal service, he enlisted again in 1940, now 44 years old, and was deployed to Hong Kong. There, he served with the small Allied garrison that was attacked by the Japanese on December 8th, 1941, just four hours after the attack on Pearl Harbor. According to his Distinguished Conduct citation:

Staff Sgt. Clark of the Canadian Postal Corps was at Headquarters of “C” Force at Hong Kong. A building in which he was quartered received a direct hit from a heavy shell. One of his officers was killed and Col. Patrick Hennessy, DSO, MC, second in command of “C” Force, was mortally wounded. With the assistance of another NCO, (Bill Overton) Staff Sgt. Clark applied a tourniquet to Col. Hennessy’s legs, placed him on a door and carried him to a spot under an iron staircase for safety. Staff Sgt. Clark went for help and had to pass a blazing building which contained 300,000 rounds of small arms ammunition which was exploding. The danger of flying bullets and enemy shells did not deter Staff Sgt. Clark, who crept through this barrage and reached the Mount Austin barracks, where an ambulance was sent for. He returned to Col. Hennessy under the same dangerous conditions with a medical officer who treated him. Then Staff Sgt. Clark assisted in carrying Col. Hennessy on a stretcher to the ambulance and to hospital while under fire.

As a prisoner, Clark knew that a successful sabotage attack on the shipyard—an “inside job,” as it were—would help the Allied war effort immensely. But he also knew that the consequences for anyone caught committing even the smallest hostile act against Nippon Kokan would be severe. The need for secrecy was therefore paramount. But as he began to plot his sabotage, Clark realized he’d need at least one trusted accomplice. After careful consideration, he approached Private Stanley Cameron of the Royal Canadian Ordnance Corps, which proved to be a prudent choice. Indeed, none of the rest of us knew about their partnership until well after the deed had been carried out.

A shipyard is a massive and highly complex industrial system. In 1943, before the age of computer automation, the basic production process could be roughly summarized as follows. A marine engineer would design, in blueprint form, drawings of a ship’s components. These parts would then be rendered into wooden moulds or templates that could be used to trace out the shape of each part on thick steel plate, which would guide the acetylene torches used to cut the steel into required form. As each part was cut from steel sheets, it would be transferred to the appropriate vessel under construction and riveted, welded, or bolted into place. The high volume of ships being produced at the shipyard, and the large number of parts contained in each one, meant that tons of paper blueprints and templates had to be stored on site. The two-building facility where they were stored comprised a single tiny nerve center within an industrial shipbuilding process that otherwise spread out over many square miles—a fact of considerable interest to anyone who might want to bring production to a sudden halt.

The crucial question was how. Since the yard worked on a 12-hour day shift, any scheme Clark developed would have to be executed in broad daylight, under the noses of Japanese guards—an impossible task. What he needed was some way to set the destructive act in motion on a delayed basis, so that it would unfold when the site was empty.

At the work sites to which they’d been assigned, Clark and Cameron began squirreling away a variety of combustibles that they could use to produce a primitive firebomb—such as paint thinner, oil, rags, oil-soaked shavings, benzine, resin, paper, and celluloid. To time the operation properly, they used a candle, which, once lit in the afternoon, would burn down for several hours until it ignited a hand-made fuse that would, in turn, set off the assembled combustibles.

It took Clark and Cameron a year—acting without the knowledge of anyone else, even fellow POWs—to gain access to the target buildings, establish a safe hiding place for the bomb, smuggle in the combustibles, and put the device together, all the while knowing that an unexpected search or a single mistake would lead to certain, and possibly gruesome, death.

It is one thing to act courageously to save yourself or one’s comrades in the heat of the battle—which, while laudable, is typically a product of reflexive instinct. What Clark and Cameron did required a more sustained kind of courage. These two remarkable Canadian soldiers risked everything to take the fight to the centre of the enemy’s heartland.

By mid-January, 1944, Clark and Cameron were ready to get even for what happened at Hong Kong. Shortly before quitting time on the afternoon of January 20th, they set up their device behind a pile of rubbish in one of the rarely inspected storerooms in the mould loft, lit the makeshift candle fuse, then marched back to Camp 3D with their comrades. At 8pm that night, with every POW in camp and accounted for, the candle burned down to the fuse and the bomb ignited, just as planned. The storage building and the neighbouring blueprint facility were engulfed in flame. Because of the nature of the combustibles, the initial incandescent blaze emitted an enormous amount of heat and smoke, and the handful of security officers on site were powerless to extinguish what soon became a raging inferno.

The result was everything Clark and Cameron had hoped for: Work at the massive shipyard ground to a halt. In the days to come, some limited construction did recommence on ships that already were near completion, but building new ships had become impossible. This included the anti-submarine vessels that the Japanese navy desperately needed.

To say that the Japanese were furious is an understatement. And the feared Kenpeitai—Japan’s military police—were soon in our camp, questioning the Canadian warrant officers and anyone else they suspected might be involved. But two things blocked their discovery of the truth. First, the pact of secrecy Clark and Cameron had agreed to had been total. No one (including me) told the police anything because, aside from this pair of conspirators, no one had anything to tell. (In fact, I didn’t discover the facts until the war was over.) Secondly, the fire had consumed the evidence. Clark and Cameron left no telltale signs that could be traced to them or any of the other POW workers.

It also became clear to us that, despite the uproar, the shipyard manager and camp commandant weren’t as anxious as you might think to find out that POWs under their command were guilty of arson—since such a finding almost certainly would have led to their own court martial and, possibly, death. (Moreover, our claims of innocence dovetailed with the Japanese view that we POWs would have neither the skill nor the courage to pull off such an audacious stunt.) And so the safer course was to conclude, at least officially, that the culprit was spontaneous combustion. With no evidence of foul play, Japanese investigators had little to go on except their suspicions, and the focus turned to rebuilding the facility’s production capacity.

With no manual work to be done at the now-dormant shipyard, the prisoners were divided up and transferred to work at other camps. (In my case, I ended up at the Ohashi prison camp in the mountains of northern Japan, whose liberation in 1945 I described in a previous Quillette article). With a rueful chuckle or two, we left the crippled shipyard and its corps of puzzled Japanese commandants.

After his release from captivity, Lieutenant-Commander Edward V. Dockweiler of the United States Navy, the senior Allied officer at Camp 3D at the time of our departure, wrote a report on the Nippon Kokan fire for American and Canadian military authorities. It read, in part:

About 20:00 hours on 18 January 1944, a large fire broke out in this yard, completely destroying the steel shed, ships outfitting stores, prisoner of war mess hall, riggers lobby, tool rooms, part of the shipfitters shop and mould loft. At this time, the yard was engaged in building escort destroyers and merchant shipping. Its tonnage production was about 8,000 tons per month. The fire was started by Staff Sergeant Clark, Canadian Postal Corps. and Private K.S. Cameron, Royal Canadian Ordnance Corps… This act of sabotage greatly crippled the production of this yard and directly minimized the Japanese war effort, and the contribution to the Allied War effort that these two men made under the handicap of being prisoners of war, cannot be overestimated. Their conduct as prisoners of war, while under my jurisdiction, was exemplary and fulfilled the highest traditions of the Canadian Army.

Staff Sergeant Clark and Private Cameron escaped detection until the end of their captivity, and both survived to return home to their Canadian families. For their brave actions, they were decorated by the King. “Charlie” Clark won the Distinguished Conduct Medal (DCM) and Private Cameron the Military Medal (MM).

Clark also became an energetic leader of the community of returning Canadians soldiers, and eventually formed the Hong Kong Veterans Association of Canada. Tragically, soon after returning home, this brave man died in a house fire. And with him perished his detailed notes of how he and Cameron had so bravely carried the war to their enemy.

Back home in Alberta, Private Cameron became active within his community as a Big Brother, Kiwanis Club member, and Canadian National Institute for the Blind (CNIB) volunteer, in which capacity he taught blind people to play golf and curl. While writing this account, I asked his family about his wartime exploits. They told me that they’d only learned of them when he was decorated and written up in the press. When asked why he hadn’t told them about it previously, Cameron had simply smiled and said he “was just doing my duty” (an admirably humble formulation that, as his 1944-era Japanese captors might have noted, wasn’t literally true).

Today is Remembrance Day in the British Commonwealth, a time to pay tribute to veterans and their sacrifices. Like others who served in the military, I witnessed many brave and selfless acts. But few were as admirable—and successful—as those of these two captured Canadian soldiers.

More information about his story may be found here and here.