BLM

America Has Serious Problems. It’s Time to Stop Blaming Them on ‘Trumpism’

It is always tempting to portray one’s political opponents as consumed by some inveterate flaw or social contaminant that marks them as fallen creatures.

Donald Trump may have been defeated in his quest for re-election. But not so the shadowy ideology he supposedly champions. “Even in defeat, the embers of Trumpism still burn in the Republican Party,” declares the Washington Post. “Trumpism wasn’t repudiated,” warns a New York Timescolumnist. “Trump may be on his way out—but Trumpism marches on,” proclaims the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. At the Guardian, it’s “Trump lives on.” At the Chicago Tribune, “Trumpism has been vindicated.” The Daily Beast ran a piece entitled “This Isn’t Enough—We Wanted a Repudiation of Trumpism,” and, to hammer home the point, added an unsettling graphics banner that reads, “Dark Victory.”

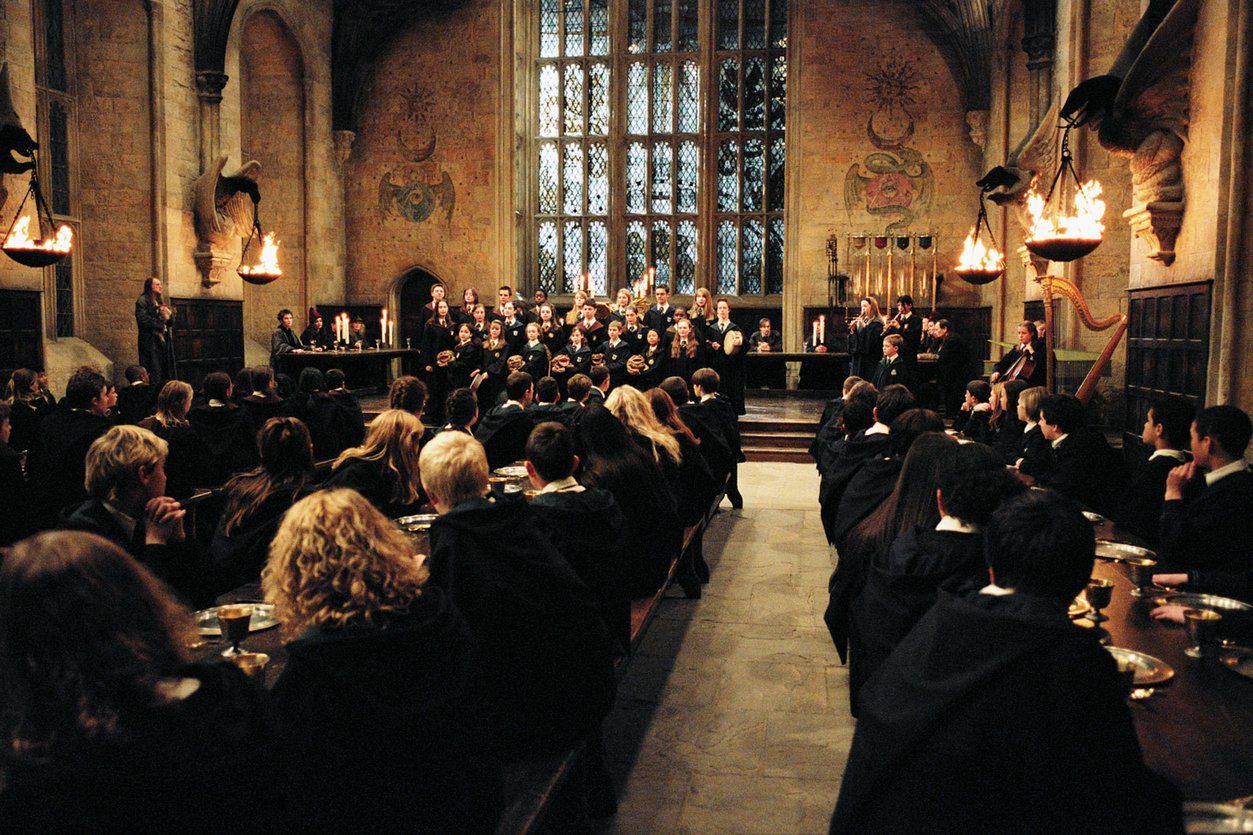

And what is this “Trumpism” of which they speak? It’s hard to say, since Trump himself was always a recklessly unpredictable populist who changed tune unpredictably to suit his own ambitions and vanities. But in the way the term is used journalistically, “Trumpism” often serves as a stand-in for all that is malignant in the world—a sort of Voldemort-like spirit nourishing itself on unicorn blood within the souls of the unenlightened. A staff critic at the Post defined it as that “unique brand of ugliness—rooted in racism, exceptionalism, recklessness, arrogance and a tendency to bully… And although white supremacy may be the better, more clinical term for what ails America, Trumpism is a useful, colloquial alternative. It encompasses an even wider category of people that includes not just avowed racists who have publicly supported the president but also those who downplay the problem, or align with it for personal gain, or are simply unwilling to acknowledge its history and persistence.”

Quillette is not an American media outlet. Insofar as we’ve offered commentary on Donald Trump and the 2020 election, our editorial focus has been aimed at the social, cultural, technological, and academic factors that lie upstream from electoral politics more generally. To the extent our writers embrace any political agenda, they typically have opposed the centrifugal forces that are acting on western democracies—including both crude populism on the Right, and anti-liberal doctrines of race and gender on the Left. What we have observed, time and again, is that these two forces feed off each other. And to the extent anything called “Trumpism” actually exists, it will only be nourished by liberals’ insistence that the president’s appeal is rooted solely, or even primarily, in “white supremacy.” Trump rose to power on the idea that the “elites” despise the values and concerns of ordinary citizens. Even as his presidency enters its twilight, those same elites seem intent on vindicating his thesis.

Back in February, long-shot Democratic presidential aspirant Andrew Yang would sometimes be asked why he didn’t bash Trump—or even mention him prominently—in his campaign speeches. At his New Hampshire campaign events (some of them documented for Quillette at the time), he would explain that no matter what happened to Trump in 2020, the conditions that led to his election in 2016 would still need fixing. And no, he did not mean America’s “unique brand of ugliness” or some other secularized formulation of original sin. Rather, Yang was referring to the complex set of factors that had led to large sections of the middle class watching steady jobs and comfortable lives get upended by automation, outsourcing, and the consequent decline of unionized manufacturing.

When Trump was elected in 2016, Yang told one Nashua, N.H. crowd, “I said, ‘Oh my gosh, tens of millions of our fellow Americans decided to take a bet on this narcissist reality TV star’… So I started looking for an explanation as to why Donald Trump won. And you all know all the explanations—racism, Russia, the electoral college, Hillary Clinton, low turnout, sexism. [But] I’m a numbers guy. So I looked through the numbers for an explanation. And I found one: We eliminated over four million manufacturing jobs in this country… And where were those jobs? Ohio, Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, Missouri, Iowa… There’s a straight line between the adoption of industrial automation in a voting area and the movement to Trump.”

“If you were born in the 1940s, in the United States, there was a 93 percent chance you were going to do better than your parents. That’s the American dream. That’s what brought my family here. That’s what we all aspire to for our kids. But if you were born in the 1990s in this country, you’re down to a 50-50 shot, and it’s declining fast. Donald Trump is our president today because he had a very simple, powerful, compelling message… He said he was going to make America great. What did Clinton say in response? America’s already great.”

Yang’s presidential bid went nowhere because he’s a policy mechanic, not a salesman. And the solutions he offered would require Americans to rebuild the gearbox of their economy—a difficult job—as opposed to just swapping out the hood ornament and slapping on a Black Lives Matter bumper sticker. He told followers that “Amazon is like a giant spaceship” sucking up retail jobs. “The most common job in the economy is a retail clerk—and the average retail clerk is a 39-year-old woman making between $8 and $12 an hour. What is her next job opportunity when the store closes?” It’s a fantastic question, especially for Democrats whose party has traditionally sought to align itself with the working class. But it was liberals, not conservatives, who cheered on the angry protestors who turned COVID-stricken retail neighborhoods across the country into combat zones. Many of the stores and restaurants that put plywood up over their windows will simply never open again, and, in some cases, for reasons that have nothing to do with COVID-19 or “Trumpism.”

It is always tempting to portray one’s political opponents as consumed by some inveterate flaw or social contaminant that marks them as fallen creatures. This is a pattern that plays out on both sides of the political spectrum. And Trump himself often has demagogued whole swathes of America, sometimes lapsing into genuinely hateful language and bald-faced conspiracy theories. But Yang was correct when he observed that Trump was always the symptom, never the disease. Moreover, as much as Trump enabled the worst qualities of nativist conservatives, he also brought out the most condescending and intellectually lazy tendencies of well-educated liberals. As economist Jeff Rubin recently noted, the ostensibly progressive rhetoric of upper middle class knowledge workers now bears little relevance to the hardships of impoverished Americans—of whatever race. And so pretending that America can simply be healed by curing some fictional disease called Trumpism isn’t just wrong, it’s counterproductive, because as we are already seeing, these rites of political exorcism inevitably will mean doubling down on race hustling and hashtag hectoring instead of actually addressing the problems that led to the rise of Trump (and Bernie Sanders, for that matter).

Rick Ross, a recent guest on the Quillette podcast, defined a cult as exhibitingboth (1) “an absolute authoritarian leader without any meaningful accountability that so dominates the group he or she virtually comes to define it,” and (2) a “process of intense indoctrination that inhibits critical thinking and ultimately leads to undue influence, often called ‘brainwashing.’” Ross was speaking on the subject of NXIVM, but it was alarming to observe how much of what he said applied to modern political radicals, with Trump’s most fervent followers embodying the personality-cult element, while strident social-justice activists are more likely to exhibit the second, doctrine-based prong of cult-think. Fired up within their respective social-media silos, both sides highlight the irrational aspects of the other’s belief systems, while lacking self-awareness in regard to their own drift into radicalism. It often takes an extraordinary development to penetrate these belief systems, and it is worth wondering whether last week’s election result will do the trick.

Among Republicans and conservatives (the two groups are not coterminous), the lessons to be gained are somewhat obvious: Populism is a dead end, whether in its left- (think Venezuela) or right-wing variations, because there are no crowd-pleasing slogan-based solutions to the biggest problems of our time—including the ongoing pandemic, income inequality, substance abuse, global warming, terrorism, crime prevention, and the crisis in mental health. And as Trump departs from the political stage (however noisily), the simple fact of his defeat may help hammer this lesson home to those who need to hear it.

Among progressives, the situation is more complicated, because while the Democrats won the presidency, their preferred narrative—the decisive rising up of progressive Americans, led by a vanguard of people of color—didn’t really unfold. As USA Today summarized the exit-poll data, “Trump improved over his 2016 performance among Black women (+4 percentage points), Black men (+5), Latinas (+3) and Latinos (+4).” Overall, minority voters still overwhelmingly picked Joe Biden. But what does it say that a third of self-described Latino men, and a quarter of Latino women, picked Trump; or that Trump’s support was up among Asians and Muslims, and apparently doubled among self-identified LGBT voters. Astonishingly, Trump earned a larger share of non-white voters than any Republican presidential candidate of the last 60 years. Only a true political cultist could imagine that all of these people are “white supremacists.”

Or, perhaps, a New York Times columnist. With the Times having spent much of the last four years presenting Trump as an agent of purblind racism (in parallel with the newspaper’s own internal witch hunts), op-ed columnist Charles Blow pronounced it to be “personally devastating” that Trump’s share of the black vote jumped, in relative terms, more than 50 percent. “Also, the percentage of LGBT voting for Trump doubled from 2016. DOUBLED!!!,” he added, in a flourish of Trump-esque all-caps. “This is why LGBT people of color don’t really trust the white gays.” And then, in a final et tu flourish following a brief drive-by on “white women,” he cites Trump’s higher share of the Latino and Asian vote as “yet more evidence that we can’t depend on the ‘browning of America’ to dismantle white supremacy and erase anti-blackness.”

Four years ago, we were assured by the great and the good that the Trump phenomenon was driven by racist white rednecks. But the main reason Trump lost this election is that his support plummeted markedly—an 18 point drop, if exit polls are to be believed—among white men. All in all, the United States just observed a 16 percent decrease in the racial voting gap, as compared to 2016. As Jamil Jivani told Quillette podcast listeners, there is good news here for those who are inclined to look past a Times columnist’s bizarre claims that gay, Muslim, Hispanic, Asian, and black voters are conspiring to prop up “white supremacy” and “anti-blackness.”

Many black leaders, for instance, openly admitted that Trump’s plan to create 500,000 new black-owned businesses was actually more ambitious than anything the Democrats were proposing. Politico has reported that Trump’s surprisingly strong showing in Miami may be traced to a backlash against the excesses of Black Lives Matter, whose protests have resulted, if only indirectly, in the destruction of countless minority-owned businesses and a huge surge in violent crime. As Quillette contributor Asra Nomani has noted, many immigrants are repelled by Democratic efforts to implement affirmative action plans that massively reduce the representation of Asians at elite schools. (Even in liberal California, voters are sick of such policies.) And one can hardly fault socially conservative voters of all stripes—including Muslims—for being put off by a Democratic presidential nominee who parrots faddish theories of gender. Only in the mind of a true zealot do all of these issues get conflated down to a Manichean electoral division between good and evil, with non-white, non-straight, non-male pro-Trump voters written off as heretics afflicted with the woke version of what Marxists once called “false consciousness.”

But there is hope. Cultists can be deprogrammed. And so can whole political movements, and even nations. In the run-up to this election, a commonly expressed fear was that the United States would melt down into riots and arson, on an even larger scale than occurred over the summer. But aside from sporadic violence—including the now-usual nihilistic rampages in Portland—things have been relatively peaceful during the past week.

It could just be a short-term respite—a breather for exhausted culture warriors eager to continue the violence and tribalism once they get fired up again. Or, perhaps, it’s a sign that both sides are finally interested in finding ways to resolve their differences without recourse to the extremism and race rhetoric that became a defining feature of the American political landscape during the Trump era.