Activism

Slack Wars: Corporate America’s Woke Insurgency

Labor leaders no longer even pretend they can staunch the layoffs, and so their focus increasingly has turned to questions of editorial direction and ideology, over which they still believe they can exert leverage through the back door of social media.

Between 2008 and 2019, total newsroom employment in the United States declined by 23 percent. At newspapers, the drop has been more than 50 percent. Journalists are hardly to blame for the underlying causes of this contraction (which include the long-term shift from physical to digital media, and the growing ad-market share controlled by Google and Facebook). But they can be blamed for the gratuitous acts of self-sabotage that are exacerbating the industry’s woes. Many journalists—and even their unions—now seem more preoccupied with denouncing heresies among colleagues than with maintaining their audience and livelihoods.

At the New York Times, to take one obvious case study, op-ed editor James Bennet was hounded out in June after publishing a column that reflected widespread frustration with violent social-justice protests. Bari Weiss, one of the newspaper’s brightest stars, decided to follow Bennett out after enduring an internal newsroom campaign of verbal bullying, which included bizarre claims that she was a racist and a Nazi (these slurs targeting a Jewish woman whose recent book is titled How to Fight Anti-Semitism). And this past weekend, the New York Times Guild, the union representing the newspaper’s media workers, publicly denounced one of the Times’s own columnists on Twitter—before deleting its tweet, which the union now claims was posted “in error.”

Times media columnist Ben Smith reports a union source to the effect that the original tweet was sent out by a rogue Guild official “without any internal discussion, causing a furor in Slack and drawing heated objections from others.” Yet either way, the union is already on record as advocating a regime of “sensitivity reads” to control what reporters and pundits are allowed to publish. In normal times, journalists and their unions fight for editorial independence and viewpoint diversity against bosses who push for centralized control. In 2020, it’s the journalists themselves who are championing a rigid ideological monoculture.

Quillette often focuses on disputes within rarified professional subcultures because these milieus serve as canaries in our cultural coal mines. The professional duties of media workers require them to hold each day’s news developments up to the light of prevailing orthodoxies. As public figures, they tend to have prominent social-media platforms from which they can prosecute their grievances. And so they provide us with a chance to study the dynamics of in-house corporate mobs that otherwise operate behind closed doors.

At Hachette Book Group, employees actually demonstrated in the street earlier this year, claiming to “stand in solidarity with Ronan Farrow, Dylan Farrow, and survivors of sexual abuse”—this as part of a successful (if completely libelous) campaign to force their bosses to cancel publication of Woody Allen’s memoir. At Hachette UK, meanwhile, a group of employees tried to refuse to work on JK Rowling’s new book, on (false) claims that Rowling is a transphobic bigot. At the Guardian, employees have passed around petitions demanding that editors block all but the most doctrinaire viewpoints on gender dysphoria (claiming that to do otherwise would create an atmosphere that’s “hostile to trans rights”). When Toronto Star reporter Rosie DiManno recently protested the elevation of “race and gender” columnist Shree Paradkar to a parallel “ombud” position in regard to BIPOC complaints about editorial content, Star journalists responded not by protesting Paradkar’s clear conflict of interest, but instead by demanding DiManno’s public humiliation. At Spotify, staffers have threatened to walk out or strike because the company has refused to grant them editorial control of Joe Rogan’s Spotify podcast. (According to one report, the company has held no fewer than 10 separate meetings with workers who believe that Rogan’s content is transphobic and, in the words of one aggrieved staffer, makes “many LGBTQAI+/ally Spotifiers feel unwelcome and alienated.”)

It’s always unclear how many of the workers who join these mobs actually read the social-justice manifestos they sign. Commenting on analogous campaigns at universities, Princeton professor Joshua T. Katz has noted in Quillette that while some signatories presumably “believe in every word,” many sign without reading, simply as a lazy way to signal virtue, appease activist colleagues, or avoid falling under suspicion in regard to their own lapses. But regardless of the underlying motives, these spectacles have encouraged the practice to spread to other sectors, especially in liberal tech hubs such as New York, Seattle, and San Francisco.

In some cases, employers are pushing back, especially when large sums of money are at stake. The hyper-progressive internal politics of Facebook have been documented here at Quillette by one of the company’s former senior managers. Yet Facebook still makes millions from pro-Trump ads. At Spotify, which reportedly paid $100 million to get exclusive rights to Rogan’s podcast, it’s perhaps not surprising that Spotify management “has a limited tolerance for the mutiny on deck.” At Coinbase—a large San Francisco-based digital currency exchange, CEO Brian Armstrong recently issued an explicitly apolitical mission statement, and stuck with it even after activist-minded subordinates threatened to quit. (According to Armstrong, about five percent of his staff are walking away.) While Hachette caved to the anti-Allen mob in New York, it’s important to remember that its UK counterpart held firm on defending Rowling. And that Star workers who came for DiManno never got the struggle session they demanded. No senior editors signed on to the anti-DiManno letter, and the issue seems to have simply disappeared—perhaps because DiManno, unlike Paradkar, has a real following among ordinary readers. Once you get beyond the public postures, corporate culture is still, ultimately, about making money.

When these disputes play out on social media, one often sees conservatives demanding that managers “grow a spine” and face down their activist staff. Armstrong, in particular, has won praise for his stance among some tech entrepreneurs, including computer scientist Paul Graham, who told his 1.2 million followers that “@brian_armstrong leads the way. I predict most successful companies will follow Coinbase’s lead. If only because those who don’t are less likely to succeed.” Yet the dynamic that’s developing here isn’t a simple narrative of woke staffers versus hard-headed management. Over the summer, recall, many corporate social-media accounts turned into a non-stop slide show of Black Lives Matter slogans and solemn #allyship messaging. As York University management professor David Weitzner noted in Quillette, these campaigns often serve as a quick and cheap gambit to enhance a company’s brand, and thereby advance the core mission of increasing shareholder value.

Moreover, some tech leaders really do seem to have become true believers—including, apparently, at Yelp, which recently announced a dubious feature that would allow users to tag local businesses as racist. And it’s interesting to observe that Armstrong’s most vicious critic is none other than former Twitter CEO Dick Costolo, who denounced the Coinbase CEO as one of those “me-first capitalists who think you can separate society.” He added that such people “are going to be the first people lined up against the wall and shot in the revolution” and that he would “happily provide video commentary.” (Costolo’s own worth is estimated at $300 million. During his tenure as Twitter CEO, ironically, he bemoaned the proliferation of exactly this type of abuse on his own platform.)

As economist Jeff Rubin told Quillette podcast listeners last month, the relationship between workers and business owners has been in flux for all sorts of reasons in recent decades. At newspapers such as the Times and the Star, union leaders once understood their role as maximizing wages and staff count, while reducing the demands placed on workers. This conflict caused all sorts of frustrations and inefficiencies. But at the very least, it anchored editorial staffers and their unions in the real world of money, head count, and punch clocks. Even if the unions spouted Marxist jargon, they also created rigidly hierarchical bureaucracies that couldn’t easily be co-opted by lone activists acting on passing trends.

That world, of course, no longer exists. In almost every private-sector industry, journalism included, unions are a pale shadow of their former selves. Labor leaders no longer even pretend they can staunch the layoffs, and so their focus increasingly has turned to questions of editorial direction and ideology, over which they still believe they can exert leverage through the back door of social media. But since their favored social-justice doctrines cast ideological dissent as a quasi-medical issue of “harm” and “safety,” the primary effect of these campaigns is to stifle staffers’ own editorial freedoms—often in a way that, paradoxically, aligns perfectly with management’s branding efforts.

Which is to say that many of these internal disputes aren’t really ideological battles at all, since both labor and management inhabit the same political subcultures, and are inclined to share the same beliefs (or at least pretend to, for public consumption). Rather, they are tactical disagreements about how big the money pot has to get before litmus tests are waived. The number, as we’ve seen, sits somewhere between Woody Allen and Joe Rogan.

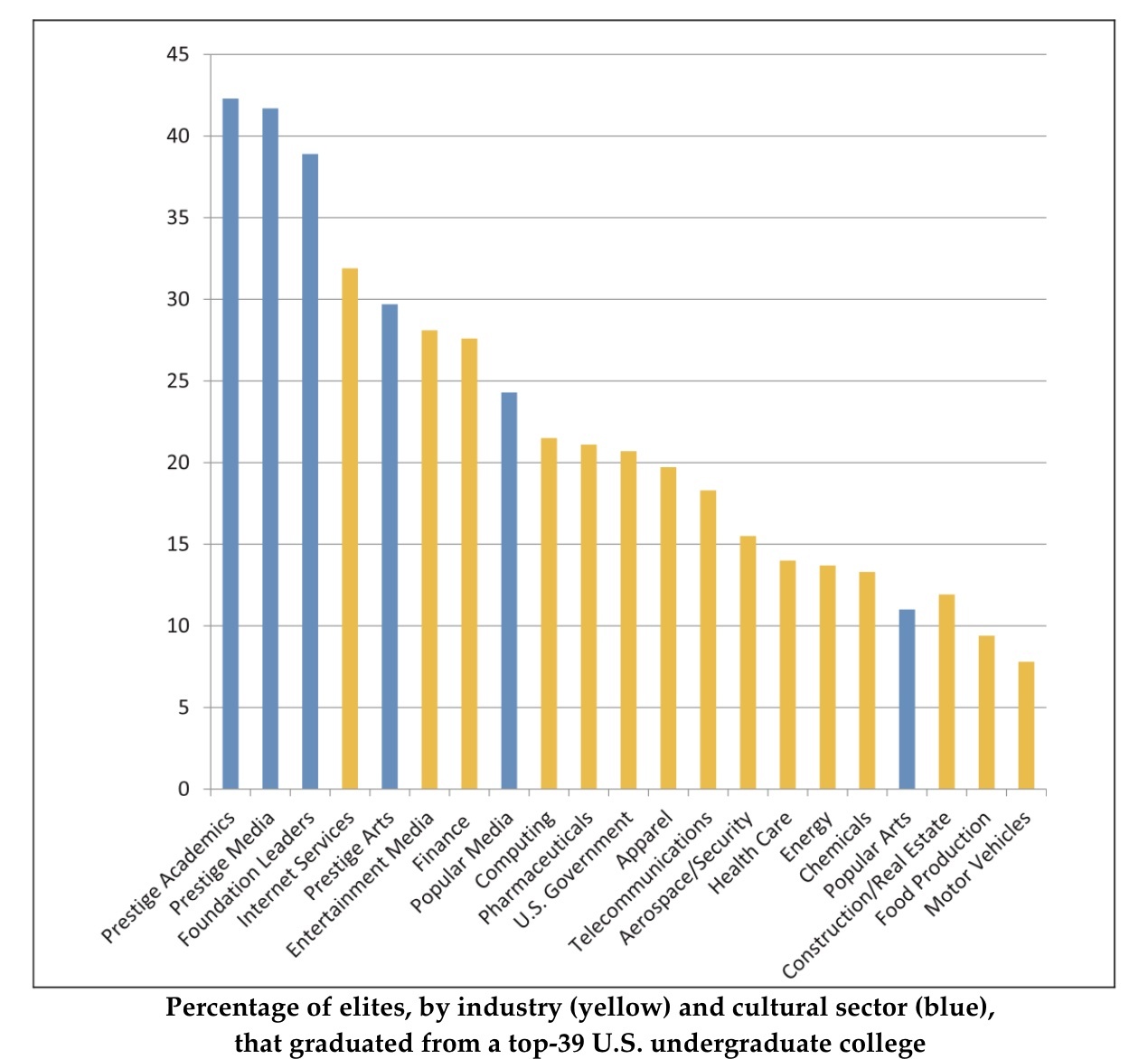

Steven Brint, an organizational sociologist at Stanford University’s Center on Poverty and Inequality, recently led a research team that investigated the educational backgrounds of what he calls “cultural elites.” In the April 2020 edition of Sociology of Education, his team reported data showing that there is a growing cultural chasm not only between elites and non-elites, but also within elite circles. While the business elites who run manufacturing, processing, farming, energy, health, aerospace, pharmaceuticals, and construction tend to be drawn from a relatively wide array of university backgrounds, the same isn’t true of cultural elites—academics, media workers, and artists—whose professional functions “depend on the quick absorption and sophisticated manipulation of symbolic media.” For instance, over 30 percent of the leaders of America’s most prestigious media outlets, academic departments, and Internet services have an undergraduate degree from one of the country’s top-rated colleges. In the field of motor vehicles, the corresponding figure is eight percent. For food production, it’s nine percent. For construction, 12 percent.

This, in turn, has created a cycle of academic and professional self-selection within cultural silos—including at leading tech companies, where executives and entry-level knowledge workers alike tend to emerge from the same elite schools. The old Marxist-inflected tribalism of worker-versus-capitalist has been replaced with a groupthink model that spans business hierarchies.

This kind of ideological homogenization is especially apparent at Silicon Valley operations that employ small groups of high-value workers who create software used by millions. Cold War-era widget-manufacturing companies were bland and risk-averse in their public-facing values, because workers were primarily concerned with wages and working conditions, while customers were sensitive to brand and reputation. But in the tech economy, where the focus is on getting first to market with a dominant app or software platform that can generate a natural monopoly through system effects, a customer’s values don’t count for much. What matters most is attracting the small handful of elite engineers and software developers whose genius can truly make or break a product. And so the values these companies peacock are those that align with the educational environments that enroll the best talent, especially the Ivy League, Stanford, and the best University of California schools.

There’s still a class-based cultural conflict going on, but it’s playing out between industries, not within them. As Brint and his team hypothesized, cultural elites who trade in symbolic manipulation tend to “achieve prominence through peer or expert recognition,” while elites who sell more tangible goods and services tend to “gain prominence though popular acclaim.” This divergence explains, among other things, why rank-and-file Spotify workers (who earn more than $120,000 annually, according to one report) seek to muzzle a podcast that gets over 190 million monthly downloads. Joe Rogan, a state university dropout, is accountable to the global English-speaking public. Spotify workers are accountable to a few dozen colleagues, all with largely identical viewpoints, on Slack.

Some readers might notice the irony at play here. The crux of the social-justice belief system is the claim that society’s elite structures are shot through with powerful forces that invisibly prop up privileged cliques. This is why managers at every large organization now spend much of their time on programs aimed at detecting, analyzing, and suppressing increasingly esoteric forms of implicit bias—often with the active encouragement of the youngest and lowest paid workers and their union representatives (if any). Yet the result of this process has been to simply shift the locus of privilege from professional rank and socioeconomic status to markers of doctrinal purity developed in a small cluster of high-status schools and companies—schools and companies that (surprise, surprise) are stuffed with the sons and daughters of privileged cliques.

After all, who else but society’s most pampered specimens can seriously entertain the delusion that the biggest threat to a worker’s psychological health is a book by JK Rowling or a podcast host who expresses belief in the idea of biological sex? The problem we face isn’t that young workers don’t respect the values of their older bosses. It’s that the most culturally influential and prominent sectors of the economy now operate in an ideological universe that their own customers increasingly find unrecognizable.