Environment

As City Budgets Shrink, It's Time to Rethink Recycling Programs

Instead of relying on impractical edicts from politicians, and the costly labor of municipal employees who gather a jumble of mostly worthless material that needs to be sorted, let the market determine what’s worth recycling, and let private operators figure out how to collect it efficiently.

The COVID recession has caused tax revenues to plummet, forcing cities and states to make painful budget cuts. But as they struggle to fund schools, parks, public safety, and other essential services, there’s one simple and painless way for governments to save money: Rethink recycling. The goal should be to transform the practice from a virtuous-seeming exercise that drains funds from core public services, to one by which price signals assure taxpayers that diverted materials are actually recycled.

When recycling programs became common three decades ago, they were sold to taxpayers as a win-win, financially and environmentally: Cities expected to reap budget savings through the sale of recyclable materials, and conscientious taxpayers expected to reduce ecological destruction. Instead, the painful reality for enthusiastic, dutiful recyclers is that most recycling programs don’t make much environmental sense. Often, they don’t make economic sense, either.

The chief buyers of American recyclable materials used to be Asian countries, chiefly China, where wages were low enough to justify labor-intensive recycling operations. But as part of Beijing’s “National Sword” policy, China began banning imports of “foreign trash” in 2017. Other Asian countries also began imposing their own restrictions. Meanwhile, reduced demand sent prices tumbling. The market price for mixed paper, for example, dropped from $160 to $3 per ton from March 2017 to March 2018.

As a result, cities that once collected some revenue for bales of recyclables (though typically not enough to cover the extra costs that recycling introduces into a municipal budget) must now pay to get rid of them. In many cases, they simply send them to landfills.

The situation in San Jose, California is illustrative. Long considered a municipal model in this area (including by the federal Environmental Protection Agency), the city provides financial incentives for two contractors to divert as much household waste as possible from the general refuse stream and into recycling. As an EPA report puts it: “San Jose pioneered the use of contractual rates, fees, taxes, and contractor compensation to provide incentives for generators, waste haulers, recyclers, composters, and even landfill operators to focus first on reducing and reusing materials, then recycling, digesting and composting the rest.” (The recycling contractor receives larger payments for households that recycle a higher percentage of their trash: approximately $5.40 per household for diversion of 40 percent to 42 percent of waste, $6.50 for 42 percent to 44 percent, $8.30 for 44 percent to 46 percent, and so on.) This arrangement once worked to the benefit of both the city and its contractors. But in 2018, local reporting highlighted that waste was piling up due to China’s limits on recycling imports. The situation has become similarly dire for plastics recycling in California more generally. Plastic redemption centers that once collected empty bottles outside grocery stores are disappearing.

San Jose, like many other municipalities, has remained committed to a “zero waste” goal—even though such ambitions are clearly out of reach. Indeed, the city’s “diversion rate,” praised by the EPA, was likely misleading even during better times: Reprocessors in China were rejecting much of the materials they received, often dumping them in Chinese facilities that are more environmentally damaging than their US equivalents. The bottom line is that cities such as San Jose have been spending large sums on “recycling” programs that often are just subsidized trans-Pacific waste-shipment and -burial programs. A better approach would be to limit curbside recycling, incentivize the private sector to collect what’s valuable and usable, and send the remaining trash straight to a landfill or incinerator.

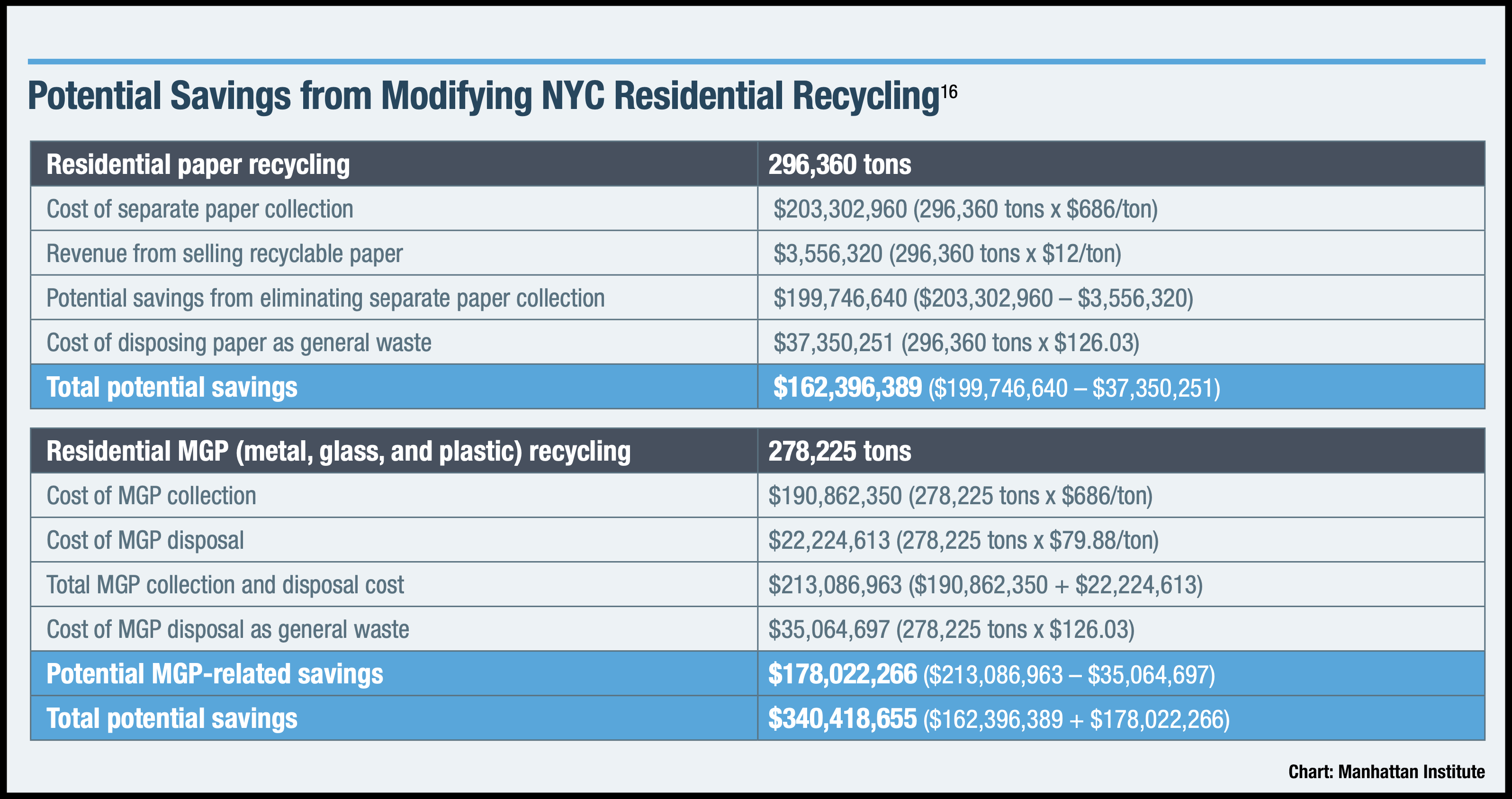

A recent study from the Manhattan Institute analyzes the potential savings that might be generated by such a policy shift. New York City, for example, spends more than $400 million annually on recycling, nearly as much as the budget of its parks department. Diverting recyclables to regular garbage trucks (and paying for disposal in a landfill) could save more than $250 million per year.

As it is, the city’s parks are failing—and the city’s handling of waste is largely to blame. A recent New York Times feature offered a devastating glance at the trash-pile-up problem currently plaguing the parks and rendering some of them unusable. The Department of Sanitation reports it lacks the trucks and personnel to collect the trash in overflowing litter containers. By rethinking recycling, city officials could pick up the trash, restore the parks, and rectify the $84 million cut inflicted on parks in pandemic-driven budget cuts.

The numbers vary, but the story is largely the same in other cities. The city of Rye, NY, with just 15,000 residents, spends some $500,000 annually to collect recyclables. In Boston, the city’s recycling contract calls for it to pay between $125 to $160 per ton to dispose of recyclables, compared with just $80 per ton for general trash. Dallas, the city with the rosiest recycling finances of the municipalities analyzed in the Manhattan Institute study, spends $14 million annually on separate collection—a cost which homeowners absorb—thanks to a long-term fixed-price contract and a landfill owned by the city itself. “The current economics of it, absolutely, it would make more sense to landfill,” says Tim Oliver, the head of the city’s Department of Sanitation Services. “I think that’s the case across the country—or the world for that matter—in most cases.”

Of course, progressive mayors with ambitious climate goals want to signal their commitment to the environment—a laudable goal. But the environmental benefits associated with recycling are largely confined to metal, cardboard, and certain kinds of paper. Recycling other materials makes little if any difference in carbon emissions. For instance, the greenhouse benefits from recycling a plastic bottle are so miniscule that even just rinsing the bottle in water heated by coal-powered electricity yields a net increase in carbon emissions.

Meanwhile, recycling has its own environmental drawbacks, like the burning of fossil fuels in the trucks and ships carrying recyclables (especially on international trips). Many western recyclables have ended up polluting the seas, because these materials were sent to Asian, Latin American, and African waste-processing facilities that allowed plastics to leak into rivers—a phenomenon that is responsible for virtually all the consumer plastics that wind up in the oceans.

The end of curbside recycling programs wouldn’t mean the end of recycling. As noted above, certain items could still be profitably recycled by private companies that already collect these materials from stores, office buildings, and factories. Instead of relying on impractical edicts from politicians, and the costly labor of municipal employees who gather a jumble of mostly worthless material that needs to be sorted, let the market determine what’s worth recycling, and let private operators figure out how to collect it efficiently. That approach may not make give politicians and environmentalists the same warm and fuzzy feeling they get from the universal residential pickup programs. But it’s the best way to do the most good at the lowest price.