Top Stories

The Contradiction That Broke the Modern Right

The parties that have previously sold themselves as staunch defenders of freedom are now the parties most susceptible to authoritarianism.

Conservative parties throughout the West are in crisis. This may not be fully understood by simply looking at recent election results, as conservative parties have continued to win elections. But these parties are currently in a state of ideological flux, and their commitment to existing liberal democratic principles and institutions are in noticeable decay. The conventional perception of conservative parties as steady and secure governing hands has made way for a more volatile and agitated form of politics. Parties that have routinely positioned themselves as defenders of the established order have instead become actively hostile to it. Conservative parties, the Economist noted last year, are now “on fire and dangerous.”

This phenomenon is most evident in the United States, where the Republican Party has become a wholly owned subsidiary of Donald Trump; a political actor guided solely by parochial instincts and personal narcissism, untethered to any intellectual understanding of his party’s traditions. The party’s convictions are now driven solely by fealty to the president, regardless of his actions. While Trump may be a singular figure, the tension he represents—between principle and parochialism—has also created the divisions within the Conservative Party in the United Kingdom that were aroused in response to the country’s membership of the European Union.

In Australia, the Liberal Party has been engaged in a decade-long civil war that has seen a number of hostile leadership changes (including against two sitting prime ministers). Although this struggle for control of the party has ostensibly been a battle over the recognition of climate change, that issue is the local proxy for the wider internal problems that conservative parties are facing. In Western Europe, meanwhile, the political systems have provided enough oxygen for radical reactionary parties to form and significantly eat into the electoral support of traditional conservative parties (although they have also drawn support from social-democratic parties).

What has become apparent is that conservative parties—and movements outside these parties that push and pull at them—are now increasingly uncomfortable within the prevailing norms of their societies and political systems. Most worryingly, these parties are demonstrating a notable suspicion towards the restraints placed upon their action by liberal democratic principles; constitutionalism, the rule of law, the protection of individual and minority rights, market-orientated economies, and the scrutiny of the press.

While there is an increasingly clear comprehension of the populist and illiberal impulses that have been developing within Western conservative parties, the question that still requires investigation is: why? Why have parties that have previously characterised themselves as forces for political and social stability transformed themselves into agents of instability? To answer this question, we need to understand what modern conservative parties have been advocating, why these ideas have undermined their own core values and inclinations, and how this has in turn instigated their current agitated and chaotic behaviour.

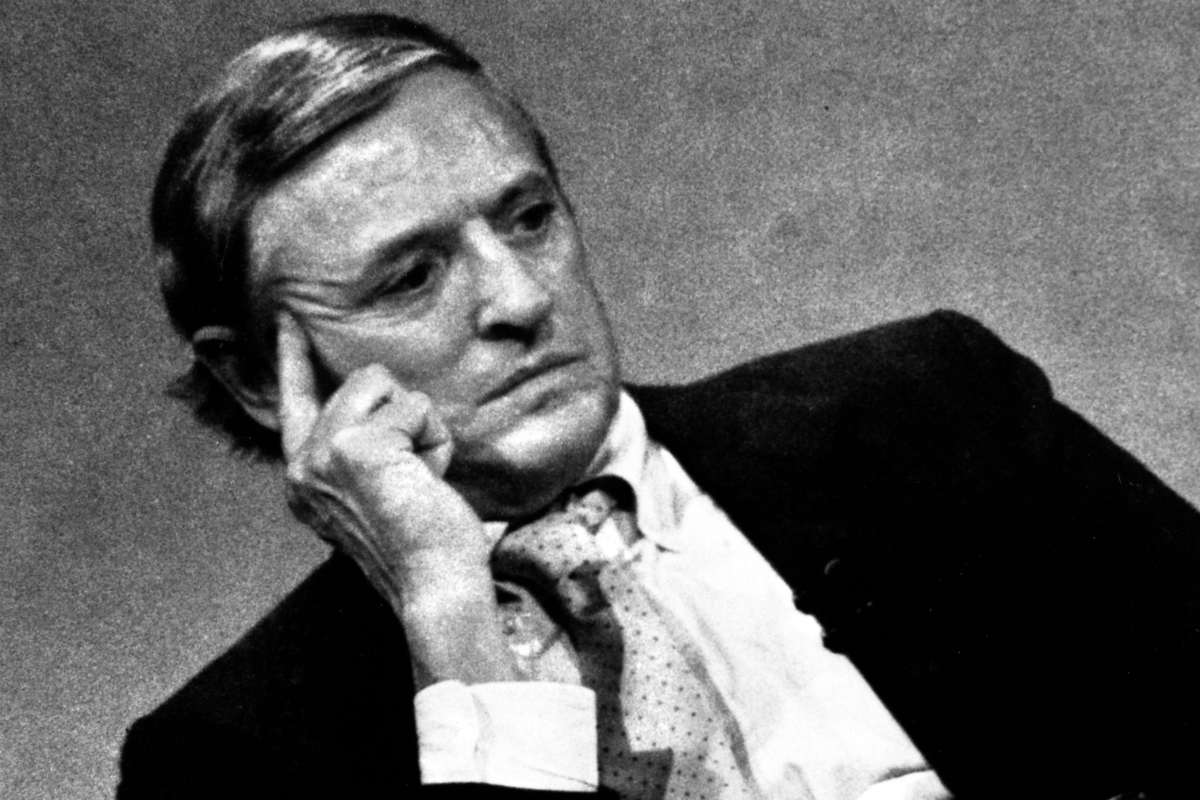

Modern conservative ideology has a reasonably well-known origin story; in the early-1960s William F. Buckley’s National Review magazine sought to develop a bulwark against the global threat of communism, and began to build a coalition of cultural and social traditionalists with the ardent economic liberalism advocated by the Austrian and Chicago schools of economics to create a new ideological conception of conservatism. The calculation was simple enough; if communism was the all-pervasive hand of the state in a country’s economic activity, then we, as anti-communists, must therefore be staunch free-marketeers. With the elections of Ronald Reagan in the US and Margaret Thatcher in the UK, the project had fully taken root; conservatism was the advocacy of ever-freer markets.