China Syndrome Series

The China Syndrome Part II: Transmission and Response

The human rights record of the Chinese Communist Party provides ample evidence of its capacity for repression and cruelty, and therefore ample opportunities for condemnation.

Note: This is the second part of a four-part series of essays looking in detail at China’s role in the COVID-19 pandemic. Part One looked at the circumstances surrounding the initial outbreak; this part looks at the discovery of human-to-human transmission and the immediate response; Part Three investigates allegations that the pandemic began in a “wet market” or that the virus escaped from a lab in Wuhan; Part Four examines charges that the Chinese have falsified their pandemic data.

There is evidence that, in mid-January, Chinese officials withheld suspicions that sustained human-to-human transmission was occurring. Nevertheless, most of the claims about Chinese mendacity and its implications have been wildly exaggerated. A useful account of the ways in which the local health authorities delayed the release of crucial information was published on February 5th, 2020, in China News Weekly, but apparently deleted from their website almost immediately. Fortunately, it was archived and eventually translated by China Change, a website created by Chinese human rights activists in the US. A fair-minded story published by Associated Press also illuminates the role played by the national authorities in the delay. And on March 6th, the Wall Street Journal published an essay which helps establish a timeline of who knew what and when about human-to-human transmission. (Any claim I make in what follows for which I don’t provide a link is supported by at least one of those sources.)

As I explained in Part One of this series of essays, by early January, the Wuhan Health Commission and the national health authorities had realised that a new virus closely related to SARS-CoV-1 had emerged in Wuhan and was responsible for a cluster of pneumonia cases there. On several occasions during the first half of January, both the local authorities in Wuhan and the national authorities in Beijing denied that sustained human-to-human transmission was occurring. On January 5th, the Wuhan Health Commission issued a statement saying that the number of cases had risen to 59, but that “no clear evidence of human-to-human transmission has been found and no infections by medical personnel.” The Commission made no further public announcements about the status of the outbreak until January 11th, when it announced that the number of cases had risen to 41 and that one person had succumbed to the disease on January 9th. This statement also said that “no health worker has been found to have contracted the disease” and reiterated that “no clear human-to-human transmission has been established.” The period between January 6th and January 10th, during which no new cases were announced, coincided with the convening of Hubei’s “Two Sessions,” the annual meeting of the city’s party officials which ran from January 6th–17th.

On January 15th, the Commission published a document in which it slightly revised its position. “No clear evidence of human-to-human transmission has been found,” it said, “and the possibility of limited human-to-human transmission cannot be ruled out, but the risk of sustained human-to-human transmission is low.” The same day, it announced that one woman may have contracted the virus from her husband. This limited acknowledgment that human-to-human transmission might be occurring took place two days after the first case was reported in Thailand—a 61-year-old Chinese woman who had arrived from Wuhan on January 8th and reported regularly visiting Huanan Seafood Market before the onset of symptoms. On January 15th, Li Qun, the head of the China CDC’s emergency centre, told Chinese state television that “the risk of sustained human-to-human transmission is low.” This seems to have been the first update from China’s national health officials since the identification of SARS-CoV-2 was announced on January 9th.

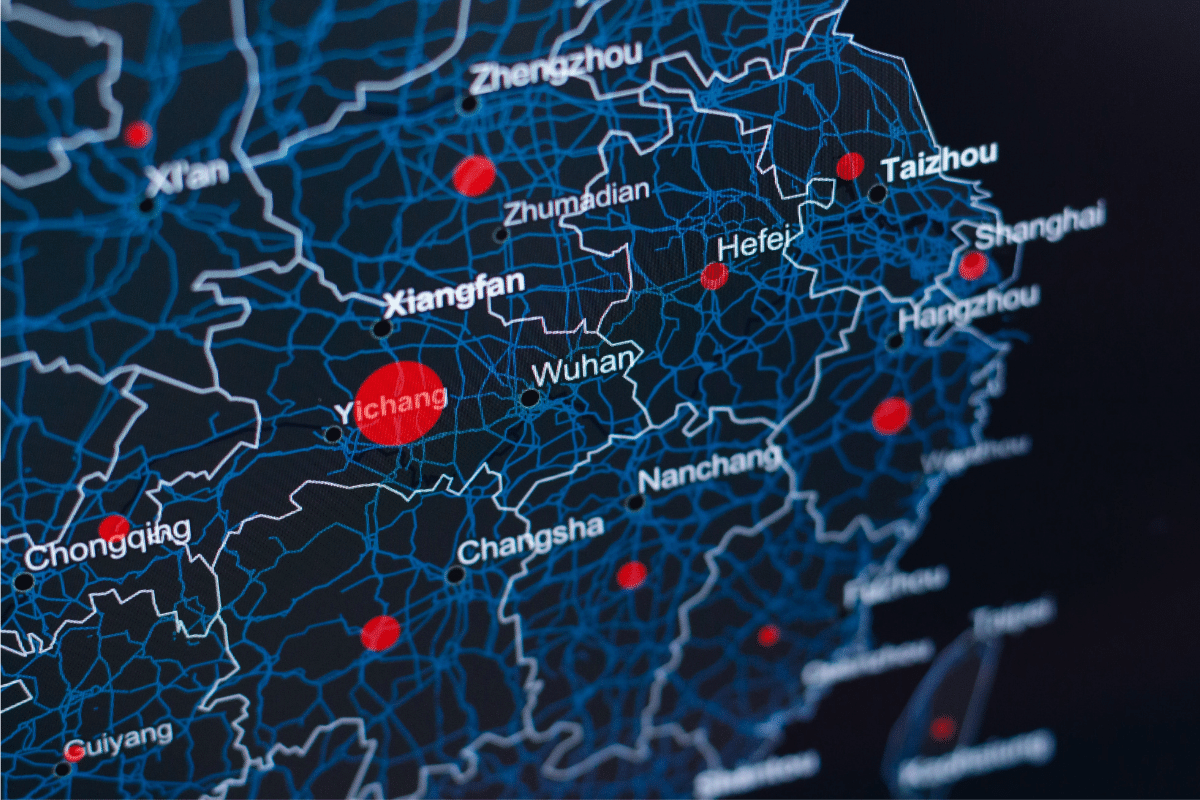

But as more cases began to appear outside China, developments inside the country accelerated. The Wuhan Health Commission had not reported any new cases since January 11th, but on January 17th, the day Hubei’s “Two Sessions” conference concluded in Wuhan, four new cases were announced. On January 18th, the Commission announced 17 new cases, then 136 on January 19th. The same day, the National Health Commission announced the discovery of the first Chinese case outside Wuhan, in the city of Guangdong. Finally, on January 20th, the head of a team of experts sent to Wuhan by the National Health Commission the previous day announced on television that human-to-human transmission was occurring, and that 14 healthcare workers had been infected while caring for a single patient. That night, Xi Jinping made his first public statement about the outbreak and acknowledged the gravity of the rapidly developing situation. From this point forward, the Chinese authorities acted quickly and it should have become clear to everyone, both in China and abroad, that a pandemic was now likely.

The annual Chinese New Year migration had been underway since about January 10th and millions of people had already moved across the country. Cases started to multiply in other Chinese cities and in various other countries around the time human-to-human transmission was publicly acknowledged, but this didn’t prevent the local authorities from going ahead with public events that gathered thousands of people in Wuhan during that period. On January 21st, the National Health Commission began a daily count of cases, and the following day, the Wuhan Health Commission mandated mask-wearing in public. On the evening of January 22nd, officials announced that Wuhan would be placed under quarantine the following morning at 10am and that no traffic would be allowed in or out of the city. On January 24th, quarantine was extended to several other cities in Hubei province and Wuhan authorities began construction of a purpose-built treatment centre for COVID-19 patients. The same day, most other provinces declared a level 1 public health alert, the highest emergency level. It was around that time that the number of cases exploded and that the first studies of the outbreak started to emerge. This was the beginning of a massive effort to suppress the epidemic across China that continues to this day.

The first case

In order to determine whether China suppressed information about human-to-human transmission, it’s useful to review the time it took for US health authorities to announce that sustained human-to-human transmission was occurring at the beginning of the 2009 swine influenza pandemic. The transcripts of every CDC press briefing during that period allow us to establish a timeline and compare it to China’s response in 2020. The CDC’s report announcing the discovery of the virus in samples from two different children was published on April 21st, 2009. At that time, human-to-human transmission had still not been established, let alone sustained human-to-human transmission (defined by the CDC as “transmission from person-to-person through several cycles”). The report did note, however, that “the lack of known exposure to pigs in the two cases [increased] the possibility that human-to-human transmission of this new influenza virus [had] occurred.”

By April 23rd, 2009, the interim deputy director for science at the CDC was saying he believed that human-to-human transmission was occurring, but that the CDC “certainly [didn’t] know the extent of the problem.” On April 24th, the acting director of the CDC explained that unconnected cases suggested sustained human-to-human transmission, but he remained circumspect. On April 27th, the WHO raised its pandemic alert status to phase 4, which indicated that sustained human-to-human transmission of the virus was occurring in at least one country. The acting director of the CDC now said that, although they had “only one case of documented by viral testing person-to-person spread,” they were “seeing significant rates of respiratory infection among contacts,” which suggested that the virus was “acting like a flu virus” and was spreading from person to person. So, 13 days after the virus was first sequenced on April 14th, the health authorities made it clear that sustained human-to-human transmission was occurring. But the CDC had already indicated that it believed human-to-human transmission was occurring 10 days after the virus was first sequenced and only three days after the discovery was announced.

Human-to-human transmission of SARS-CoV-2 was announced 17 days after the virus was sequenced by the National Institute of Viral Disease Control and Prevention and 11 days after this discovery was made public. That it took China significantly longer to announce unequivocally that human-to-human transmission was occurring suggests that China wasn’t entirely forthcoming during that period. It’s not clear whether the local authorities or the national government was responsible for this obfuscation and it’s not easy to ascertain exactly what the various actors knew at each point. Even so, a lot of reporting on this topic has been poor and it’s important to correct the record.

In an article for National Review entitled “The Comprehensive Timeline of China’s COVID-19 Lies,” Jim Geraghty wrote:

According to a study in the Lancet, the symptom onset date of the first patient identified was “Dec 1, 2019… 5 days after illness onset, his wife, a 53-year-old woman who had no known history of exposure to the market, also presented with pneumonia and was hospitalised in the isolation ward.” In other words, as early as the second week of December, Wuhan doctors were finding cases that indicated the virus was spreading from one human to another.

If this were true, it would mean that China had evidence of human-to-human transmission at the beginning of December 2019, but continued to deny that it was occurring until January 20th, 2020. However, the ellipsis in Geraghty’s quote of the Lancet study excludes information that completely changes the meaning of this passage. Here is what it looks like when quoted in extenso:

The symptom onset date of the first patient identified was Dec 1, 2019. None of his family members developed fever or any respiratory symptoms. No epidemiological link was found between the first patient and later cases. The first fatal case, who had continuous exposure to the market, was admitted to hospital because of a 7-day history of fever, cough, and dyspnoea. Five days after illness onset, his wife, a 53-year-old woman who had no known history of exposure to the market, also presented with pneumonia and was hospitalised in the isolation ward.

As the Lancet study makes perfectly clear, it is not the wife of the first case who fell ill, but the wife of the first fatal case—a different individual who died on January 9th. And it explicitly states that none of the first case’s family members developed any fever or respiratory symptoms. This same misrepresentation was repeated on the blog of a Chinese dissident. I don’t know whether Geraghty edited this passage himself or just copied it from somewhere else without double-checking the source. But whoever inserted the ellipsis was being deceptive.

Even if members of the first case’s family had developed symptoms, it still wouldn’t follow that China knew or even suspected that human-to-human transmission was occurring by the second week of December. As the Lancet paper notes, December 1st is the date of the onset of symptoms—none of the patients included in the study were hospitalised until December 16th. More importantly, the information in that study is the result of a retrospective epidemiological investigation conducted in January after the Chinese realised the outbreak was caused by a new coronavirus. As we have seen, nobody in Wuhan had any idea that a new virus had started to spread until late December, but a lot of commentary seems to assume the Chinese knew then what we know they only learned much later.

The Taiwanese warning

Another widely repeated story is Taiwan’s claim that it warned the World Health Organisation (WHO) about human-to-human transmission in late December, and that this warning was ignored. On March 20th, the Financial Times reported the following:

Taiwan has accused the World Health Organisation of failing to communicate an early warning about transmission of the coronavirus between humans, slowing the global response to the pandemic. Health officials in Taipei said they alerted the WHO at the end of December about the risk of human-to-human transmission of the new virus but said its concerns were not passed on to other countries.

[…]

Taiwan said its doctors had heard from mainland colleagues that medical staff were getting ill—a sign of human-to-human transmission. Taipei officials said they reported this to both International Health Regulations (IHR), a WHO framework for exchange of epidemic prevention and response data between 196 countries, and Chinese health authorities on December 31.

This claim certainly sounds damning and it has been used by numerous commentators and politicians to accuse both China and the WHO of a cover-up. But it’s simply not true. Taiwan did not immediately publish the email in which it had allegedly given this warning, and when it did so on April 11th following a WHO denial, it turned out that it said nothing of the kind. The full text of the December 31st message read:

News resources today indicate that at least seven atypical pneumonia cases were reported in Wuhan, CHINA. Their health authorities replied to the media that the cases were believed not [to be] SARS; however the samples are still under examination, and cases have been isolated for treatment.

I would greatly appreciate it if you have relevant information to share with us.

Thank you very much in advance for your attention to this matter.

No mention is made of human-to-human transmission, nor does the email say anything about healthcare workers getting sick, so the claim of advanced warning of human-to-human transmission was just a propaganda stunt on the part of Taiwan. At this point, even the Chinese had not confirmed that SARS-CoV-2 was responsible for the cluster of pneumonia in Wuhan. So, the notion that Taiwan already knew that and had also figured out that human-to-human transmission was occurring is preposterous.

A somewhat defensive statement released by Taiwan the same day explained that “public health professionals could discern from [the wording of the email] that there was a real possibility of human-to-human transmission,” because the email talked about “atypical pneumonia” and said that cases had been “isolated for treatment.” Needless to say, this is a world away from the unambiguous warning Taiwan initially claimed it had delivered, and which it said had been scandalously ignored. Indeed, the first statement published by the WHO about the outbreak on January 5th also states that “all patients are isolated” and refers to “cases of pneumonia of unknown aetiology.” So, if public health professionals could have reasonably discerned that human-to-human transmission was likely from the wording of Taiwan’s email, they could equally have drawn the same inference from the WHO’s assessment five days later.

In the same statement, the Taiwanese authorities went on to say:

In mid-January, the Taiwan CDC dispatched experts to Wuhan to gain a better understanding of the epidemic, the control measures taken there, and patients’ exposure history. Based on preliminary research, Taiwan determined that this form of pneumonia could indeed spread via human-to-human transmission.

This, too, is demonstrably false. It is true that, in mid-January, China allowed Taiwanese experts to visit Wuhan, and that they held a press conference on January 16th upon their return. Here is the statement published by Taiwan’s CDC on January 20th:

On January 15, 2020, Taiwan CDC was notified by the Chinese Centre for Disease Control and Prevention that the total number of cases of the novel coronavirus-associated pneumonia remained at 41, including six severe cases, one death, and seven cases that had been discharged from the hospital. On the other hand, on January 16, 2020, Japan announced the first imported case of the Wuhan novel coronavirus. The case developed fever during his stay in Wuhan, but he did not visit the Huanan Seafood Market, which is linked to most cases. Nevertheless, it was possible that he came into close contact with patients of unexplained pneumonia. Taiwan CDC will continuously closely monitor the development of the case. Since confirmed cases that had not visited the Huanan Seafood Market have been subsequently reported in Thailand and Japan, limited human-to-human spread in Wuhan cannot be ruled out. Additionally, as the source of infection is still under investigation, Taiwan CDC has raised the travel notice level for Wuhan City to Level 2: Alert, advising travellers planning to recently visit Wuhan and other neighbouring areas in China to take personal precautions to ward off infection. [Emphasis mine.]

Does this sound like the Taiwanese health authorities had already “determined that this form of pneumonia could indeed spread via human-to-human transmission”? The Wuhan Health Commission had said much the same thing the day before once they realised a woman might have been infected by her husband. It’s quite possible that the Chinese concealed information relevant to the possibility that human-to-human transmission was occurring from the Taiwanese experts during their trip to Wuhan. But that doesn’t change the fact that Taiwan had not determined that human-to-human transmission was occurring by mid-January, let alone in late December.

On December 31st, the Taiwanese health authorities began screening passengers from Wuhan, and this prudence and distrust of the Chinese served them well. But nothing Taiwan has said or done proves that Beijing was suppressing knowledge of human-to-human transmission or that Taipei was somehow privy to information that the Chinese government and the WHO lacked. Taiwan’s claim that it tried to warn of human-to-human transmission seems to have been nothing more than disinformation intended to damage China and discredit the WHO. If that was indeed the intention, it has been astonishingly successful. Even though the story has been comprehensively debunked, it is still widely believed and repeated, including by President Trump who tweeted this on April 17th, six days after the text of Taiwan’s email had been made public:

Why did the W.H.O. Ignore an email from Taiwanese health officials in late December alerting them to the possibility that CoronaVirus could be transmitted between humans? Why did the W.H.O. make several claims about the CoronaVirus that ere either inaccurate or misleading….

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) April 17, 2020

From uncertainty to urgency

It is not easy to determine exactly when the Chinese health authorities concluded that sustained human-to-human transmission of SARS-CoV-2 was occurring, not least because establishing human-to-human transmission is itself very difficult to do when a new virus is identified. Since the implications of such a finding can be enormously consequential, health officials tend to move cautiously from “it is not known if” through “it is possible” or “cannot be ruled out,” then “it is likely that” and finally to “it has been established” as they amass and scrutinise the emerging data. If the Chinese health authorities didn’t know that human-to-human transmission was occurring, this is admittedly not necessarily exculpatory, because sometimes people don’t know something they ought to know. Nevertheless, we must be careful not to ascribe knowledge to the Chinese they couldn’t possibly have had at the time.

There are two fundamental points about human-to-human transmission that are often missed in these discussions and this explains much of the confusion around this topic. First, human-to-human transmission is not an on-or-off affair, it sits on a continuum. Even the distinction between limited and sustained human-to-human transmission is a gross oversimplification. In principle, if a virus can be passed from one person to another, then it can also be passed from that second person to a third. But the ease with which a virus is contracted and transmitted can vary enormously, so there is no precise moment at which anyone can determine that sustained human-to-human transmission, as opposed to limited human-to-human transmission, is taking place. Interpersonal transmission does not, by itself, indicate pandemic potential.

The second point is that a determination of human-to-human transmission relies on probabilistic judgments—it’s a gradual process during which people adjust their assessment of the probability that different kinds of human-to-human transmission are occurring based upon available but incomplete evidence. In the case of avian influenza viruses, family clusters and infections of healthcare workers have both been documented, but the CDC still deems sustained human-to-human transmission unlikely and doesn’t think a pandemic of avian influenza will occur as long as those viruses don’t mutate. So, even though China knew that some sufferers had been infected by family members or that healthcare workers had been infected by their patients by such-and-such a point in time, it doesn’t follow that they must have also known that sustained human-to-human transmission was occurring by then.

According to a story published by the China Youth Daily on January 28th, Lu Xiaohong, the director of gastroenterology at Wuhan’s Fifth Hospital, heard around December 25th, 2019, that personnel at two hospitals in Wuhan had been placed in isolation after they developed symptoms of unexplained viral pneumonia. However, she doesn’t name the facilities in question and I haven’t been able to find any evidence in support of her story, despite the fact that numerous reporters have interviewed the doctors in Wuhan, on and off the record. It is possible Lu simply misremembered the date she heard this rumour, which would be unsurprising since her claim was made more than a month later, and it’s not uncommon for people to convince themselves retrospectively that they understood what was going on before they actually did.

This conclusion is further supported by independent evidence that is hard to reconcile with her testimony. After a surveillance mechanism for pneumonia of unknown aetiology was established in Wuhan on January 3rd, epidemiological investigations began. A study based on the data collected was published in the New England Journal of Medicine in March and concluded that no healthcare workers developed symptoms before January 1st. Of course, these Chinese data could be false. But although various articles claim that healthcare workers started to fall ill in late December, I have not been able to find the name of a single one. Given the timeline of the outbreak, even if healthcare workers were getting sick by December 25th, it’s unlikely that anyone would have attributed their condition to the appearance of a new virus in Wuhan, since nobody realized it was circulating until a few days later.

What does seem to be clear is that, by January 14th, both the local and national health authorities had concluded that human-to-human transmission was probably occurring. As the Associated Press story explains, internal documents show that, on that day, the head of the National Health Commission told provincial health officials during a confidential teleconference that “the epidemic situation is still severe and complex, the most severe challenge since SARS in 2003, and is likely to develop into a major public health event.” Under a section entitled “sober understanding of the situation,” a memo obtained by the Associated Press describing the conference said that “clustered cases suggest that human-to-human transmission is possible.” Internally, China’s CDC initiated its highest-level emergency response and the National Health Commission distributed 63 pages of instructions to provincial health officials ordering “health officials nationwide to identify suspected cases, hospitals to open fever clinics, and doctors and nurses to don protective gear.”

The language used in the internal memo indicates that China’s national public health officials were still not certain that human-to-human transmission was occurring. But the urgency with which they began quietly implementing precautionary measures was by no means reflected in the public statements of Chinese officials, who continued to maintain that sustained human-to-human transmission was unlikely until January 20th, six days later. This delay arguably had serious consequences, since these events were unfolding during the Chinese New Year migration, when a lot of people left Wuhan and seeded the virus elsewhere in China.

But this fact alone should put to rest the notion that the Chinese government had known how contagious SARS-CoV-2 was since the beginning of January. That is, unless one assumes that, for reasons unexplained, the Chinese government wanted to ensure this deadly epidemic would spread throughout the country instead of being contained in Wuhan. But what possible purpose could that have served? And if the plan had been to allow the disease to simply tear through their own population, why did they then take such aggressively draconian steps to suppress it, inflicting massive damage on the country’s economy in the process? Some theories do such violence to basic common sense that entertaining them is simply a waste of time.

A far more plausible and parsimonious explanation for the actions of the Chinese government is that they simply weren’t yet convinced about just how grave the situation was. So, they hesitated to acknowledge that human-to-human transmission was occurring and delayed implementation of containment measures they knew would crater the country’s economy. This tentative response to the crisis has been replicated by governments around the world confronted with the dilemma of how to fight the pandemic, even though they knew much more about what they were dealing with than the Chinese government could possibly have known in mid-January. It should not be surprising that Chinese leaders hesitated before making decisions that would affect the lives of hundreds of millions of people and possibly jeopardise their own power. The local authorities in Wuhan faced different incentives, but even they must have known that, were a deadly epidemic to spread over the whole country because they had suppressed information, they would pay a heavy price.

Sustained community transmission is established

So, what led the Chinese authorities to conclude in mid-January that human-to-human transmission was probably occurring and why did it take so long to make this determination? The New England Journal of Medicine study found that 45 percent of the cases who developed symptoms before January 1st had no known link to Huanan Seafood Market. According to the Lancet study, the earliest confirmed case, who developed symptoms on December 1st, didn’t have any known connection to Huanan Seafood Market either. Of the subsequent cases examined (as of January 22nd when the data analysed in the paper stops), only 8.5 percent had a connection to the market. From these data, the authors conclude that human-to-human transmission had probably been occurring since mid-December.

Although the New England Journal of Medicine study analysed data collected by a monitoring system established on January 3rd, it probably took a while for a coherent picture to emerge, not least because this kind of epidemiological investigation is a time-consuming and painstaking process. To get a sense of what’s involved, consider the methodology as described in the paper:

The earliest cases were identified through the “pneumonia of unknown etiology” surveillance mechanism. Pneumonia of unknown etiology is defined as an illness without a causative pathogen identified that fulfils the following criteria: fever (≥38°C), radiographic evidence of pneumonia, low or normal white-cell count or low lymphocyte count, and no symptomatic improvement after antimicrobial treatment for 3 to 5 days following standard clinical guidelines. In response to the identification of pneumonia cases and in an effort to increase the sensitivity for early detection, we developed a tailored surveillance protocol to identify potential cases on January 3, 2020, using the case definitions described below. Once a suspected case was identified, the joint field epidemiology team comprising members from the Chinese Centre for Disease Control and Prevention (China CDC) together with provincial, local municipal CDCs and prefecture CDCs would be informed to initiate detailed field investigations and collect respiratory specimens for centralized testing at the National Institute for Viral Disease Control and Prevention, China CDC, in Beijing. A joint team comprising staff from China CDC and local CDCs conducted detailed field investigations for all suspected and confirmed 2019-nCoV cases.

Data were collected onto standardized forms through interviews of infected persons, relatives, close contacts, and healthcare workers. We collected information on the dates of illness onset, visits to clinical facilities, hospitalization, and clinical outcomes. Epidemiologic data were collected through interviews and field reports. Investigators interviewed each patient with infection and their relatives, where necessary, to determine exposure histories during the 2 weeks before the illness onset, including the dates, times, frequency, and patterns of exposures to any wild animals, especially those purportedly available in the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market in Wuhan, or exposures to any relevant environments such as that specific market or other wet markets. Information about contact with others with similar symptoms was also included. All epidemiologic information collected during field investigations, including exposure history, timelines of events, and close contact identification, was cross-checked with information from multiple sources. Households and places known to have been visited by the patients in the 2 weeks before the onset of illness were also investigated to assess for possible animal and environmental exposures. Data were entered into a central database, in duplicate, and were verified with EpiData software (EpiData Association).

In other words, even with everyone working as hard and as fast as they can, something like this is going to take time. So, it’s not as if, once the surveillance system was established, the Chinese were immediately in a position to identify the contacts of sick people who had no connection to Huanan Seafood Market and, from there, the emerging patterns of infection.

Moreover, as the study notes, the reagents necessary to laboratory-confirm cases by RT-PCR were not provided to Wuhan until January 11th, so before that samples had to be sent to the National Institute for Viral Disease Control and Prevention in Beijing to be tested. Bear in mind that, at the time, the virus had only just been sequenced there and that researchers were still in the process of confirming that it was responsible for the outbreak. As they explained in a study published on January 23rd, in the process they had to develop and validate tests to detect SARS-CoV-2 in swabs that, for obvious reasons, didn’t previously exist. The Chinese health authorities could not have known that human-to-human transmission was occurring at the beginning of January because they didn’t yet have tests to confirm suspected cases.

As the memo obtained by the Associated Press suggests, the Chinese health authorities didn’t really start thinking sustained human-to-human transmission was likely until around January 14th. They may have reached this conclusion a bit earlier, but almost certainly not much earlier, because they were barely able to conduct PCR diagnostics before January 11th. Of course, this information comes from Chinese researchers, so some scepticism is justified, but this timeline is consistent with what we know about the technical challenges involved in dealing with a new virus and what we have seen in other countries that had the benefit of hindsight. It is also consistent with how long it took the American CDC to determine that sustained human-to-human transmission was occurring after it identified the virus responsible for the swine influenza pandemic in 2009. Had the Chinese health authorities acknowledged publicly what they were saying privately in mid-January, it would have more or less matched the 2009 timeline, so there is no reason to assume they had reached their conclusion much earlier than that.

The Associated Press conjectures that, had the doctors who leaked information about the pneumonia cases they were seeing in late December not been publicly admonished, others would have been less reluctant to share information. However, although it was obviously wrong to reprimand those doctors, I doubt this is true. First, the doctors were not reprimanded for sharing information up their chain of command, but for releasing it online without authorisation. Moreover, the health authorities had already established a pretty thorough surveillance mechanism (subject to an important caveat I will discuss shortly), so the problem was not a dearth of information. Finally, even if the reprimand handed down to doctors had not had a chilling effect on medical personnel, conducting the necessary epidemiological investigations, developing and validating the laboratory tests and producing the required reagents in sufficient quantities would still have required the same amount of time.

Health experts cited by the Wall Street Journal say the Chinese missed a lot of cases early on because they were only looking for “patients who had fever, direct Huanan Seafood Market exposure and chest scans ruling out regular bacterial pneumonia.” As a result, “they overlooked those who had come in close contact with such cases, and other patients who had no direct exposure to the market, milder symptoms or illnesses other than pneumonia.” (The Associated Press gives the same explanation.) This is consistent with the surveillance mechanism described in the New England Journal of Medicine, which provides the definition of a suspected case used between January 3rd and January 17th in the following passage:

A suspected NCIP [novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia] case was defined as a pneumonia that either fulfilled all the following four criteria—fever, with or without recorded temperature; radiographic evidence of pneumonia; low or normal white-cell count or low lymphocyte count; and no reduction in symptoms after antimicrobial treatment for 3 days, following standard clinical guidelines—or fulfilled the abovementioned first three criteria and had an epidemiologic link to the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market or contact with other patients with similar symptoms.

If the Chinese were only looking for people that satisfied these criteria, it’s not surprising that they missed a lot of cases. And, at the time, nobody knew that many SARS-CoV-2 patients exhibit only mild symptoms and sometimes exhibit no symptoms at all. They only knew that a novel virus similar to SARS-CoV-1, which appeared to kill around 10 percent of those it infected and usually produced very acute symptoms, was attacking the population. That patients were placed in isolation is not evidence that human-to-human transmission had been determined, as the Wall Street Journal and others have alleged, it is evidence only of the prudent precautionary measures that any healthcare facility might reasonably be expected to adopt when dealing with patients suffering from an aggressive and mysterious new disease. What do people think Chinese doctors were going to do with those patients? Stack them on top of each other and lick their eyeballs?

Yuen Kwok-yung is a microbiologist and specialist in infectious diseases who advised the national government in Beijing and the authorities in Hong Kong. This is what he told Caixin when they asked him why Hong Kong had declared the situation “serious” as early as January 4th:

We did not know how serious the virus was at that time, nor did we know it was a new type of coronavirus, but because the virus appeared in the winter season and we were told it was related to SARS, we decided to be very cautious, and the Hong Kong government took our opinions seriously. As scientists we should never neglect “soft intelligence,” because this kind of information can sometimes be more timely than official warnings, like animals who can sense the coming of earthquakes and reacted ahead of time.

The New England Journal of Medicine study retrospectively confirms that seven healthcare workers fell ill between January 1st and January 11th, but we don’t know when the Chinese found out they had developed symptoms or when, given the shortage of tests, their diagnoses were confirmed. I’m unaware of any case of a healthcare worker who developed acute symptoms before January 12th, when Li Wenliang, the ophthalmologist punished for leaking information about the virus on December 30th, was placed in isolation with a fever and a cough. Moreover, he tested negative several times, before a test finally came back positive on February 1st. (Another doctor died on January 25th, but he was much older and apparently wasn’t infected until January 18th. Ai Fen says she was informed that a nurse in her department was infected on January 11th, but there is no indication that she had acute symptoms or that her diagnosis had even been confirmed by a laboratory test.) So the focus on people with acute symptoms can explain why the Chinese might not have noticed that healthcare workers started to get sick in early January.

Even if the Chinese health authorities had also been looking for people with mild symptoms at the outset of the surveillance, it would hardly be surprising if they had not noticed right away that seven health care workers had fallen ill. According to this paper, in 2011, there were 7.9 healthcare workers per 1,000 people in the urban areas of China. If we use that figure to estimate the number of healthcare workers in Wuhan, we end up with approximately 87,000, and 150,000 for the metropolitan area. It wouldn’t be especially shocking if the Chinese health authorities had not noticed right away that seven of them were sick because they had been infected by SARS-CoV-2, particularly if their symptoms were mild. There must have been a lot of healthcare workers with a cough or even a fever in Wuhan at the time and the Chinese health authorities weren’t about to test them when they didn’t even have enough tests for severe cases. In fact, it is highly probable that other healthcare workers were infected around that time but never diagnosed with COVID-19 because they only suffered mild symptoms.

When a team of experts was dispatched to Wuhan by the national health authorities on December 31st, they apparently failed to find clear signs of human-to-human transmission. A second team of experts was sent over there on January 8th, but according to the Associated Press, they also failed to find to unearth any clear signs of human-to-human transmission. That Wang Guangfa, the leader of that second team (who fell ill after his return to Beijing on January 16th), later declared that he “always suspected it was human-to-human transmissible,” doesn’t mean that he’d found any clear evidence to support this suspicion. So, it is unlikely that anyone, not even the local health authorities, had concluded that human-to-human transmission was occurring during the first 10 days of January. Some people probably suspected as much, but clear and sufficient evidence was almost certainly not available until the national health authorities concluded that human-to-human transmission was probably occurring, sometime between January 10th and January 14th.

In Hong Kong, meanwhile, Yuen Kwok-yung told Caixin that six members of a family of seven, including one person who hadn’t travelled to Wuhan (unlike the others who had just returned from a trip over there), were admitted to Shenzhen Hospital on January 10th, and that by January 12th, his team had “basically confirmed” they had all been infected by SARS-CoV-2. However, according to the paper in which this family cluster is discussed, not all members of that family had shown up at the hospital until January 15th. It is possible that this family was one of the clusters mentioned in the memo obtained by the Associated Press, which apparently convinced the national health authorities that human-to-human transmission was likely around that time. However, those cases were not publicly confirmed at the time, because on January 3rd the National Health Commission had ordered the institutions not to publicly disclose any case until they had been independently confirmed by the national health authorities. Had those cases been publicly confirmed right away, human-to-human transmission may have been established sooner.

A third team of experts, led by Zhong Nanshan, was dispatched by the National Health Commission and arrived in Wuhan sometime between January 17th and January 19th. The national health authorities had by now determined that human-to-human transmission was likely, but they still weren’t certain. This visit seems to be what finally cleared up any remaining doubts and convinced officials to quarantine Wuhan. According to Yuen Kwok-yung, the local health authorities were not entirely forthcoming with information during that visit and many of the people they talked to sounded like they’d been briefed about what to say. But when pressed, their testimonies convinced the team that human-to-human transmission was definitely occurring, which led to Zhong Nanshan’s public statement to that effect on January 20th. (The fact that a single patient had apparently infected 14 health care workers seemed to have played a particularly important role in their reaching that conclusion.)

So, what should we make of all this? It is unlikely that anyone, even the local health authorities, had concluded that human-to-human transmission was occurring during the first 10 days of January. Some people probably suspected as much, but clear and sufficient evidence was almost certainly not available until the national health authorities concluded that human-to-human transmission was probably occurring sometime between January 10th and January 14th. It is also clear that, between January 14th and January 20th, the national health authorities made several public statements about human-to-human transmission that didn’t accurately reflect what they were privately saying. They were certainly dissembling, but given the difficulty of determining human-to-human transmission and the patchy evidence officials were assessing, this dishonesty probably wasn’t quite as blatant as people think. Doubts were not entirely dispelled until sometime between January 17th and January 20th, after a third team of experts dispatched by the National Health Commission returned from Wuhan.

During the week that separated the confidential teleconference on January 14th and the announcement that human-to-human transmission was occurring on January 20th, the local health authorities waited to provide the information they had, possibly because Hubei’s communist party wanted to be able to hold its annual meetings undisturbed. After all, if local health authorities had noticed that 14 healthcare workers had been infected by a single patient by January 20th, they will almost certainly have noticed that healthcare workers were being infected by this patient before then. This is where critical time was lost.

The blame game begins

Is it then China’s fault that the outbreak in Wuhan led to a global pandemic that has killed hundreds of thousands of people and will cause trillions of dollars’ worth of economic damage? It is important to distinguish three questions here. First, could China have acted sooner to contain the outbreak in Wuhan? Second, even if the Chinese government could have acted sooner and contained the virus, is it reasonable to blame it for having failed to do so? Third, if we assume that China can reasonably have been expected to contain the epidemic, can Western governments legitimately blame the disasters that unfolded in their own countries on China? A lot of debate around this topic proceeds on the assumption that these questions are interchangeable, but they are not, and the answer to one doesn’t necessarily determine the answer to the others.

Could the Chinese government have acted sooner? Once the country’s health authorities determined, on or around January 14th, that human-to-human transmission was likely occurring, nothing in principle prevented the government from quarantining Wuhan immediately instead of waiting until January 23rd. So, what difference would it have made? The truth is we don’t know because estimating this kind of counterfactual is extremely difficult. One study used simulations to conclude that, had the Chinese government implemented non-pharmaceutical interventions a week earlier, the number of infections in China as of February 29th would have been reduced by 66 percent. But there’s a lot of variability in the simulations and it’s a pretty crude model. (Incidentally, this study is often used to criticise the Chinese government by the same people who claim Chinese pandemic data are faked, but the study is based on those very data.) It makes intuitive sense that locking Wuhan down a week earlier could have significantly reduced the number of infections, but we really don’t know by how much, exactly. Frankly, given how badly Western governments botched their own COVID-19 responses, I’m sceptical that a pandemic could have been averted entirely, but we’ll never know.

So the Chinese government could in theory have acted earlier and, had it done so, it might have prevented a pandemic, although I doubt it. But is it reasonable to expect that China should have acted earlier than it did? People seem to think the answer to this question is obvious. Since the government had reached the conclusion that human-to-human transmission was probably occurring by mid-January, it should have acted then, end of story. However, as I hope the foregoing discussion has shown, this kind of decision is not clear-cut. Certainly, once China did resolve to act after January 23rd, the measures it took to contain the outbreak were unprecedented—nobody had ever attempted anything like them before and nobody has gone as far since. The lockdown devastated China’s economy and Chinese officials must have known that it would have that effect. Keep in mind that, before January 20th, only three people had died and China had no idea what the infection fatality rate was. More than six months later, we still don’t know. Yet people assume that China should have known in mid-January how dangerous the virus was and they blame Chinese officials for not immediately taking decisions that they knew would inflict colossal economic pain on their country. I don’t think this position is tenable unless you assume that Chinese leaders are übermenschen, untroubled by the doubt and hesitation that afflict other ordinary people faced with terrible dilemmas under extraordinary circumstances.

Finally, let’s turn to the question of whether or not it’s reasonable to blame China for the damage inflicted on Western countries by the pandemic, on the grounds that withholding information prevented Western governments from making the correct decisions in time. During a press conference on April 18th (at 36:07 in the video), the Response Coordinator for the White House Coronavirus Task Force, Deborah Birx, accused China of withholding information that would have allowed US authorities to know what they were dealing with. It was only thanks to the information passed on by European countries, she added, that American lives had been saved. This claim is by no means unique to Birx, it is ubiquitous and bipartisan. In a recent ad released by Joe Biden’s campaign, Trump is accused of botching his response to the pandemic because he believed what China was telling him. This absurd narrative unfortunately promises to play an important role on both sides of the upcoming US presidential election.

No one ever specifies what China should have divulged that would have allowed the rest of the world to respond to the pandemic more effectively. By the end of January, Western countries had ample information to know that the virus demanded to be taken seriously, yet most of them failed to do so. Instead, public health officials in the West downplayed the threat even as the corpses began to pile up in Hubei province. By January 20th, cases were proliferating in China and everybody knew that sustained human-to-human transmission was occurring. By January 24th, most of Hubei, a province of 58 million people, was under strict quarantine. In the days that followed, the Chinese government began imposing increasingly drastic measures to contain the epidemic, not only in Hubei but also across the rest of the country. That the Chinese government, not a regime known for its sentimentality, had decided that such extreme measures were necessary ought to have indicated that something very serious was happening.

This conclusion should also have been clear from the studies published around that time. The Lancet study published on January 24th reported that 15 percent of the first 41 patients had already died. A further study published in the Lancet on January 30th showed that 11 percent of the 99 patients admitted to Wuhan Jinyintan Hospital had died by January 25th. Of course, those studies looked at hospitalized cases, so there were good reasons to suspect they were substantially overestimating the case fatality rate. Nevertheless, Western governments were strangely reluctant to heed these early warnings. (Another study published in the Annals of Translational Medicine on February 12th found that, among laboratory-confirmed cases recorded between January 10th and February 3rd, the fatality rate was 0.15 percent in mainland China excluding Hubei, 1.41 percent in Hubei excluding Wuhan and 5.25 percent in Wuhan.) The New England Journal of Medicine study published on January 29th concluded that SARS-CoV-2 had a basic reproduction number of 2.2, which suggested that the virus was spreading rapidly.

On January 26th, China’s health minister announced that asymptomatic transmission was possible, but several Western public officials said they were very sceptical. The following day, after the Chinese Health Commission said it believed people were infectious during the incubation period, the Australian government’s chief medical officer declared that its experts didn’t believe this was likely because it was not a characteristic of either SARS-CoV-1 or MERS-CoV. In the US, the country’s top immunologist Anthony Fauci also expressed his scepticism on NPR that day, but at least allowed for the possibility. It was only when German doctors published a letter to the editor in the New England Journal of Medicine, in which they claimed to have identified a case of asymptomatic transmission, that Western experts began to take the idea seriously. (Ironically, this claim turned out to be unfounded when it transpired that the patient believed to have been asymptomatic when she infected other people had in fact been exhibiting symptoms at the time.) Finally, by January 31st, Chinese researchers had already uploaded 41 genomes of the virus on GISAID, a public database used by researchers all over the world. In short, the notion that the rest of the world didn’t have enough information to prepare for the pandemic is a fiction.

Had China been more forthcoming about the risk of human-to-human transmission in the days between January 14th and January 20th, would it have made a difference? It may have saved lives inside China, but the effect on the Western response would almost certainly have been negligible. The US started screening arrivals from Wuhan at three airports on January 17th. After China announced on January 20th that sustained human-to-human transmission was occurring, screening was extended to a further two airports the following day, but still only for passengers flying in from Wuhan. On January 27th, a week after the Chinese public health authorities declared that human-to-human transmission was occurring, the CDC announced that passengers from China would be screened for symptoms at 20 airports, and American citizens were advised against travelling to China. China had by now already confirmed almost 2,800 cases, including more than 1,000 outside Hubei. Cases had been confirmed in every province except Tibet and officials had just announced that asymptomatic transmission was possible. Even so, the US waited until January 31st to announce a “ban” on travel from China, a decision that wasn’t effective until February 2nd and which, in any case, did not apply to citizens and permanent residents. (Amazingly, many public health experts criticized this decision at the time, on the nonsensical grounds that “viruses don’t care about borders,” and some even testified to that effect before Congress on February 5th.) In an article published on April 4th, the New York Times estimated that 40,000 people travelled to the US from China after the ban went into effect.

Although the United States waited more than 10 days after Chinese officials said that human-to-human transmission was occurring to partially ban travel from China, it was actually one of the first developed countries to take this elementary step. The European Union did not close the borders of the Schengen Area until March 17th. Some member states, such as Italy, had already imposed restrictions on travel from China by then. (Italy actually did so before the US, which didn’t prevent it from being very badly hit.) But many European countries, such as France, never took any steps to restrict travel from China. This is also true of several other developed countries, such as Canada and the United Kingdom, which refused to restrict travel from China (and then justified the decision with some very silly arguments indeed). So, even if China had been more transparent about human-to-human transmission, and we further assume the US would have imposed its partial ban on travel from China 10 days sooner, it probably wouldn’t have made any difference in the end. The US didn’t partially ban travel from Europe, excluding the UK and Ireland, until March 14th and genetic evidence shows that SARS-CoV-2 was mostly brought to New York, the most badly affected state in the US at the time of writing, from Europe.

In short, the claim that Western countries would not have botched their pandemic response had China not lied is not simply false, it is a transparent attempt by Western governments to deflect blame for their own shambolic incompetence. (This essay about the European pandemic response, or lack thereof, is particularly instructive, but one could say very similar things about the response in the US and several other countries.) In fact, many countries were able to deal with the crisis effectively, not only in East Asia but also in Australia, New Zealand, and Eastern Europe, despite the fact that, in many cases, they were more closely connected to China in general and to Wuhan in particular.

But most Western leaders and many of their public health officials didn’t seem to care about SARS-CoV-2 until it started killing people under their jurisdiction. As late as March 7th (after more than 3,000 people had died in China and the death toll had begun to climb in Italy), French President Macron went to the theatre with his wife to encourage people to continue to go out despite the pandemic. Countless other comparably clueless statements and gestures were made by public figures and their advisors in Western countries during that period, long after we knew that human-to-human transmission was possible. And yet, in spite of this ineptitude, we’re asked to believe that, had Chinese officials told them that human-to-human transmission was possible a week earlier, things would have been totally different.

The question of moral luck

On the other hand, once Chinese officials realised that sustained human-to-human transmission was occurring, they acted far more quickly and decisively than any Western government. And they did so without the benefit of a demonstration of just how dangerous this new virus could be as it attacked another country. Not only did Western governments waste weeks despite knowing more and having more time to prepare than China, but Western public health experts even criticised the measures taken by China to suppress the epidemic. Now the same newspapers who printed those rebukes are insisting that China should have taken those measures sooner.

Even if it were entirely reasonable to blame China for failing to quarantine Wuhan earlier, the recklessness and irresponsibility of certain Western governments and media outlets precludes them from doing the blaming. Not only did most of them fail to act quickly and decisively enough to prevent disaster, but some lied at least as much as the Chinese government did. This is certainly true of the French government and of the US government. Astonishingly, people seem to be happy to focus on the shortcomings of China instead of holding their own governments to account for failing to prepare for the pandemic when the seriousness of the situation became apparent. China may be a convenient scapegoat, but the citizens of Western countries should not be falling for such obvious misdirection.

Given how badly Western governments botched their response to the pandemic, there can be no doubt that, had it started in Europe or the United States instead of China, they would have fared far worse than the Chinese, even if the reasons for their failures would have been different. So, to the extent that China is blameworthy but the West isn’t, there is a lot of moral luck involved, simply because the outbreak happened to start there rather than here. We can tell the Chinese that the authoritarian nature of their regime prevented them from handling the outbreak better, but they might justifiably reply that the West’s own institutional failures would not have allowed us to do any better under similar circumstances.

Philosophers disagree about whether moral luck is really a thing. Is someone who kills a child while driving drunk really more blameworthy than someone who drove drunk but didn’t kill anyone because he was luckier? As we shall see in the next essay, the fact that the pandemic began in Hubei province was simply a matter of bad luck. But before we condemn China for its missteps, we should remember that we might not be so lucky next time. This is by no means an attempt to draw moral equivalence between the Chinese regime and Western liberal democracies. The human rights record of the Chinese Communist Party provides ample evidence of its capacity for repression and cruelty, and therefore ample opportunities for condemnation. But the country’s pandemic response is not among them. Instead, a sober assessment of what the Chinese got right and wrong is vital if all countries are to learn to appropriate lessons.

Part Three of this series can be read here.