Culture Wars

Remembering Cancel Culture’s 40-Year-Old Stepfather

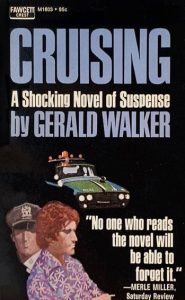

"Cruising" faced protests and boycotts from gay activists and the LGBTQ+ community, but later became a cult hit.

The worst-case scenario for a film that falls afoul of the morality police is that its release is scrapped after reviewers react negatively. In other cases, movies have been banned on a country-by-country basis. Then there are film projects that fall apart even before would-be censors have had a chance to see the final product: The very idea of the movie is simply too shocking to tolerate.

That’s what happened to Rub and Tug, which was shelved in 2018 following outrage over Scarlett Johansson playing the transgender lead. (“While I would have loved the opportunity to bring [American trans gangster Dante “Tex” Gill’s] story and transition to life, I understand why many feel he should be portrayed by a transgender person, and I am thankful that this casting debate, albeit controversial, has sparked a larger conversation about diversity and representation in film,” Johansson told the media.) Then there’s The Hunt, which saw its release scrapped—and then unscrapped—earlier this year, after Donald Trump fanned anger over a plotline that has wealthy elites hunting down poor people for sport. Clearly, cancel-culture attacks on edgy films can be led by both sides of the culture war.

A much earlier example is William Friedkin’s 1980 film Cruising, which was released 40 years ago, just weeks after Ronald Reagan took office as US President, in part thanks to the rise of Jerry Falwell Sr.’s Moral Majority movement. Yet it wasn’t homophobic Christians who demanded the film be scuttled, but gay activists.

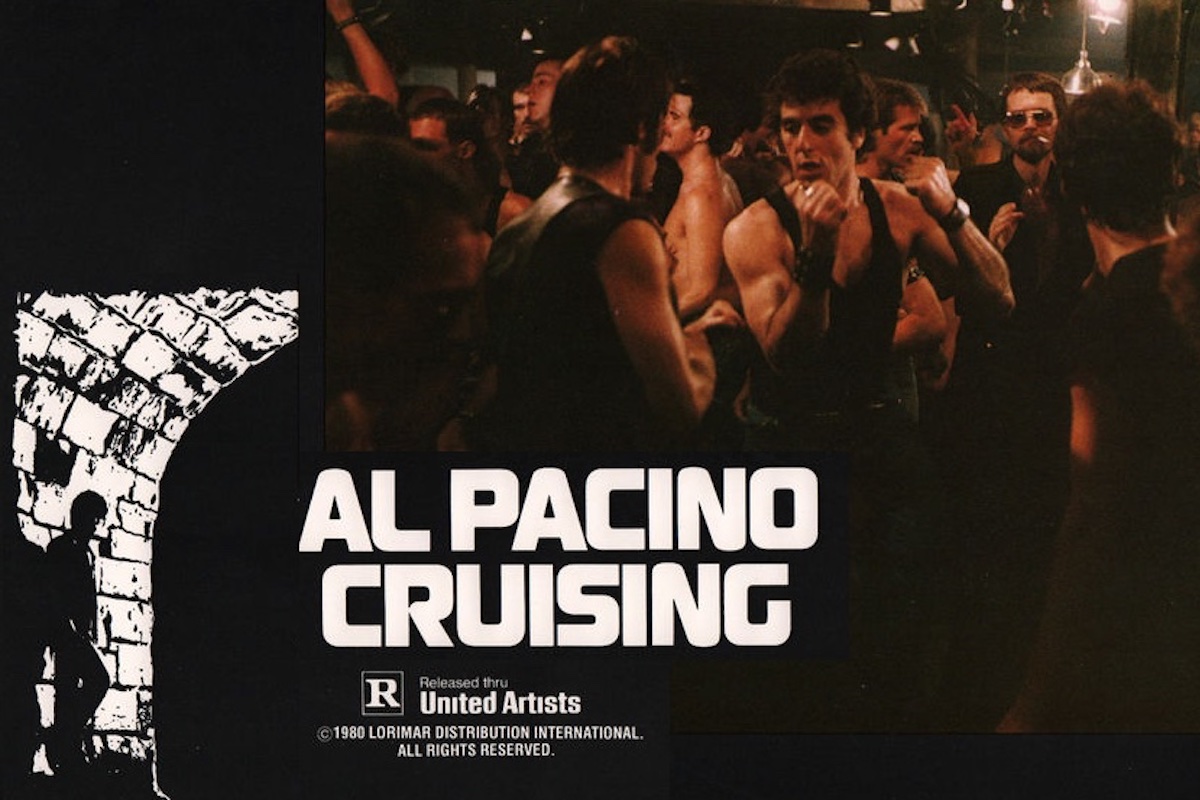

In the movie (which was eventually released), Al Pacino stars as Steve Burns, an undercover police officer seeking to track a serial killer preying on gay men within the S&M scene in Greenwich Village. The killer—dressed in black and blue leather, almost like a cop himself—lurks around bars, seeking his prey, while Burns does his best to blend in with the clientele. It’s a simple enough story—perhaps even a progressive one for its time, given the way it highlighted the mistreatment of gay men by police officers. But Cruising’s main cultural legacy lies not with its content, but with the public rallies and boycotts that greeted its production. Activists even attempted to disrupt filming at some New York City locales.

The controversy began when Village Voice columnist Arthur Bell, who’d written articles about real-life killings in gay leather bars during the 1970s, predicted the film would be “the most oppressive, ugly, bigoted look at homosexuality ever presented on the screen.” He also told his readers to “give Friedkin and his production crew hell.”

Bell had been a long-time advocate for gay rights. His first piece in the Voice was an account of the Stonewall Riots. Subsequently, he’d covered the under-investigation of gay hate crimes by New York police (as well as officers’ harassment of victims). Yet, ironically, these same concerns found their way into Cruising: At one point in the movie, the police harass a cross-dressing leather-bar patron. When he complains about it, after helping officers with their murder case, he’s practically laughed out of the precinct. But remember that Bell hadn’t yet seen the movie.

Readers took up Bell’s challenge. Movie posters were vandalized; air horns drowned out production; information was leaked on which locations were being used for filming on any given day; and, finally, rallies were held outside theaters, where picketers often outnumbered patrons. Local gay-oriented businesses even refused entry to cast and crew. Some gay extras, sick of being taunted, simply quit the set. Demonstrators blocked Greenwich Village traffic, leading to arrests. The protesters requested that New York Mayor Ed Koch rescind accommodations that had been made for film shoots.

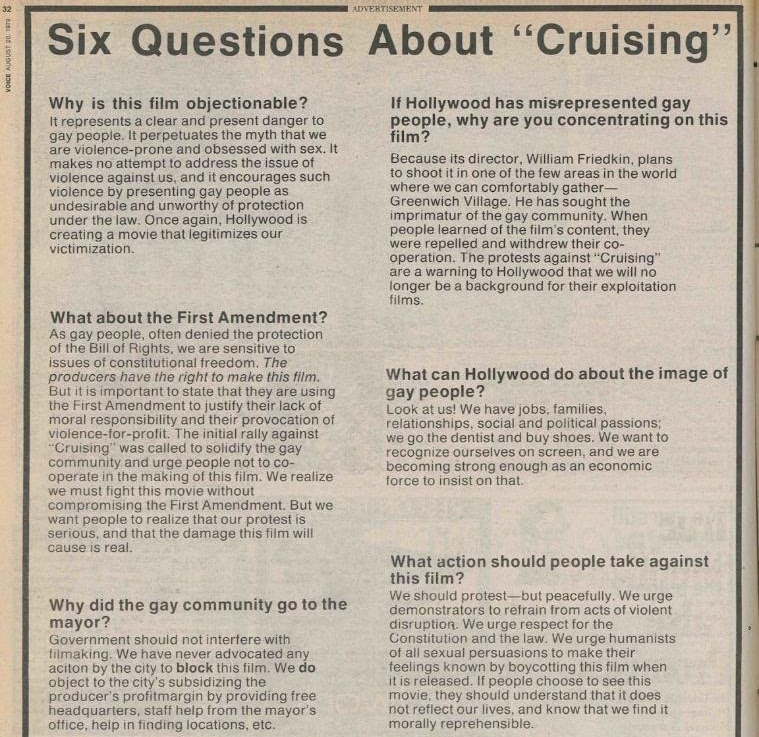

The Voice ran a full-page ad from a coalition of gay-rights groups on August 20th, 1979, arguing that the film’s depiction of the LGBT community (as we would now call it) was one-dimensional and overly focused on risqué underground sex. Protesters also suggested the film’s mere existence served as incitement to dangerous homophobia. Dianne Feinstein, now a California senator but then mayor of San Francisco, praised those organizing the boycotts on the grounds that distributor United Artists, like corporate America more generally, was a menace to ordinary Americans. (When the film opened in San Francisco theaters, she sent United Artists a $130,000 bill for the extra police deployed to keep public order.) As Michael Klemm noted in a 2007 article about Cruising, Philadelphia screenwriter Ron Nyswaner told The Celluloid Closet documentarians that he and his boyfriend had “narrowly avoided” suffering a gay-bashing in 1979 at the hands of “college jocks” who’d recently seen Cruising.

The accusations of homophobia stung Friedkin, who’d directed The Boys in the Band, acclaimed upon its 1970 release as the first major studio film to depict gay characters. But Reagan’s election had created a tense mood for coastal audiences that otherwise prided themselves on celebrating difficult art. And Friedkin’s interest in telling a story intended to provoke viewers on both sides turned him into a bête noire.

Critics also were put off by the plot’s unsettling similarity to a series of real crimes—one involving Paul Bateson, an Exorcist cast member (he was the radiological tech in the cerebral angiography scene) who’d eventually be convicted of murdering film journalist Addison Verrill (a close friend of Bell). Friedkin had directed The Exorcist, and also had a real-life friend who, like Pacino’s character, was an undercover police officer operating within New York’s gay scene. Cruising was originally based on a novel of the same name by New York Times reporter Gerald Walker, which itself incorporated many true crime details. And Friedkin’s plot adaptations further blurred the line between real life and fiction.

Pacino—who’d previously played an undercover detective in Serpico and a bank robber in Sidney Lumet’s Dog Day Afternoon (a character trying to earn money for his lover’s sex-change operation), was perplexed by the outrage. And he’s defended his character in interviews over the years, noting (correctly) that leather bars are “a fragment of the gay community,” much in the way that the mafia is a small portion of Italian-American life.

Friedkin also had run-ins with the Motion Picture Association of America, making it difficult to distribute the film. Due to its depiction of S&M counterculture, the film originally got an X rating. This was eventually downgraded to R, but only after 40 minutes of explicit material was cut. Unfortunately, those gaps render the film’s plot difficult to follow, and interfere with viewers’ ability to track the destabilization of Pacino’s character as the film progresses.

The director’s reward for perseverance was a series of scathing reviews once Cruising was finally released. The Washington Post had a pair of slams, one by Gary Arnold (“[a] shambles…even the most ardent sensation-seekers are likely to trudge out of this fiasco with their brows knit into a collective ‘Huh?’”), and another by K. Summers (“wretched”). Variety was equally unsparing, comparing it to “the worst of the ‘hippie’ films of the 1960s.”

Yet over the years, Cruising evolved into a cult hit. Boutique Blu-ray purveyor Arrow Films recently released a deluxe edition. Camille Paglia has declared it to be one of her favorite films, comparing the “underground decadence of Greenwich’s S&M culture” to The Story of O. Years after his newspaper had led the effort to cancel Cruising, the Village Voice’s Nathan Lee described the film in 2007 as a “lurid fever dream” and “a heady, horny flashback to the last gasp of full-blown sexual abandon.” James Franco centred the film’s influence within his directorial debut, Interior. Leather Bar, whose premise derives from Cruising’s missing 40 minutes.

If an updated version of Cruising were released today, one can only imagine how it would be treated. In 2015, the film Stonewall, directed by Roland Emmerich, was slammed even before its release, for supposedly whitewashing the story behind the riots. (Spoiler: It didn’t.) The 2019 comedy Adam, despite its trans director, faced boycotts and petitions on allegations of transphobia, as the premise involved a cisgender straight man whom a butch lesbian believes to be trans.

Bell, to this day, stands behind his campaign against Cruising. What he sought was “responsible art” from Friedkin, and one can understand his concerns even if one does not share them. But “irresponsible” art has a role in society: to provoke viewers and take them out of their comfort zones, inspiring empathy, and sympathy for those they may not otherwise encounter. And we’d all be poorer for losing a potential classic from the same director whose colossal run included The French Connection, The Exorcist, and Sorcerer, just because scolds had decided we couldn’t handle a complicated portrait of a world most of us will never experience.