Cinema

Remembering Reinaldo Arenas and His Enduring Lessons on Repression, Torment, and Exile

All in all, more than 130,000 set sail on rafts and boats made of rotten wood, house doors, truck tires, and anything else that could float.

In a scene from Tomás Gutiérrez Alea’s iconic Cuban film Memorias del Subdesarrollo (1968), a man looks down from his balcony at Havana’s streets. Only a few years had passed since Fidel Castro had overthrown Fulgencio Batista’s regime, and the prisoners taken during the failed Bay of Pigs invasion had just been put on trial. Like many middle-class Cubans at the time, the parents of Sergio, the film’s protagonist, had fled the country. But Sergio decides to stay. He prefers to anchor himself to his present and watch the revolution play out from his apartment. He uses his telescope to watch people, ships in the bay, places where the Republican-era statues once stood. He contemplates the city’s landscape with a sort of contempt.

Sergio wants to become a great novelist, but failing at the task. He lives off the accumulated rent his family earned before the revolution, and so is regarded by the state’s bureaucrats as a parasite. Yet the contempt is unrequited: Sergio is indifferent to the political climate in Cuba. He prefers to dwell on himself, on human injustice, on lovers from his past. In scenes inspired by European neo-realism and the anti-heroes of French New Wave cinema, Sergio’s memory is shown to have become a lonely form of inner exile. Caught between a past he disdains and a complex, ever-changing present that feels alien and threatening, he symbolized the sense of paralysis and fatalism that afflicted many of his generation.

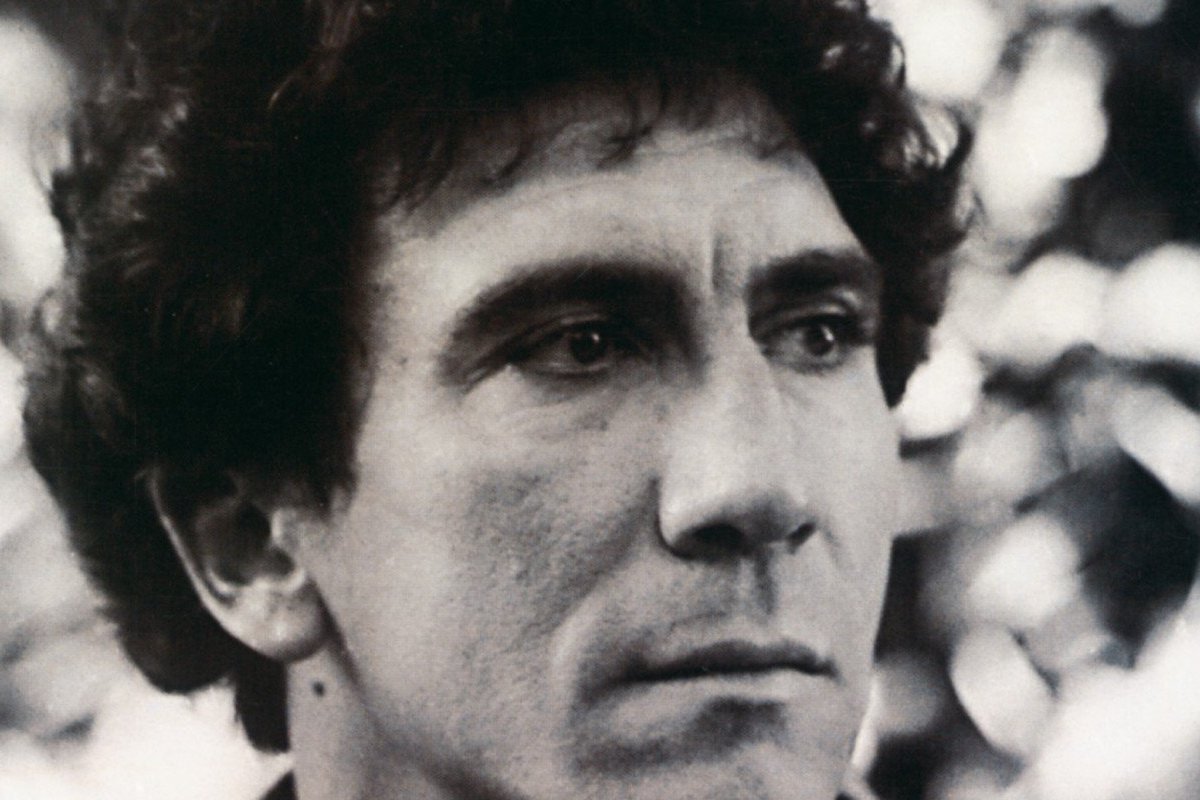

On December 7th, 1990, 22 years after the release of Memorias del Subdesarrollo, Cuban poet, novelist and playwright Reinaldo Arenas was found dead, by suicide, in the New York apartment where he’d lived his last years after escaping Cuba. Born in 1943, Arenas would have been roughly the same age as the fictional Sergio (and the actor who played him, Sergio Corrieri). But he took his life, and his art, in the opposite direction. By the time of his death 30 years ago, at age 47, the prolific writer had made a name for himself by tirelessly exposing the raw realities of Castro’s dictatorship.

Arenas was born on July 16th, 1943, in Holguín, a rural province in eastern Cuba. He moved to Havana in 1963, where he studied politics at university before dropping out and getting a job at the National Library José Martí. He published his first novel in 1967, Celestino Antes del Alba (Singing from the Well), about a peasant boy named Celestino, whose literary talent led to his family’s exile. Surreal at times, Celestino’s story unfolds as a struggle to survive ostracism. It would be the only novel Arenas was allowed to freely publish within Cuba’s borders.

He was political from an early age. At 16, the poverty he’d experienced led him to join the communist revolt against the political status quo. In his memoirs, Antes que Anochezca (Before Night Falls), Arenas recounted his first approaches to the rebels fighting against the Batista dictatorship, and then his subsequent disenchantment when the revolutionaries went from executing the old regime’s collaborators, to expropriating small businesses, to locking up “marginals,” dissidents, and homosexuals. The queer and iconoclastic Arenas—an eternal dissident, as it turns out—now was seen by the regime as a counter-revolutionary, a paria, a gusano (worm), an “enemy of the state.”

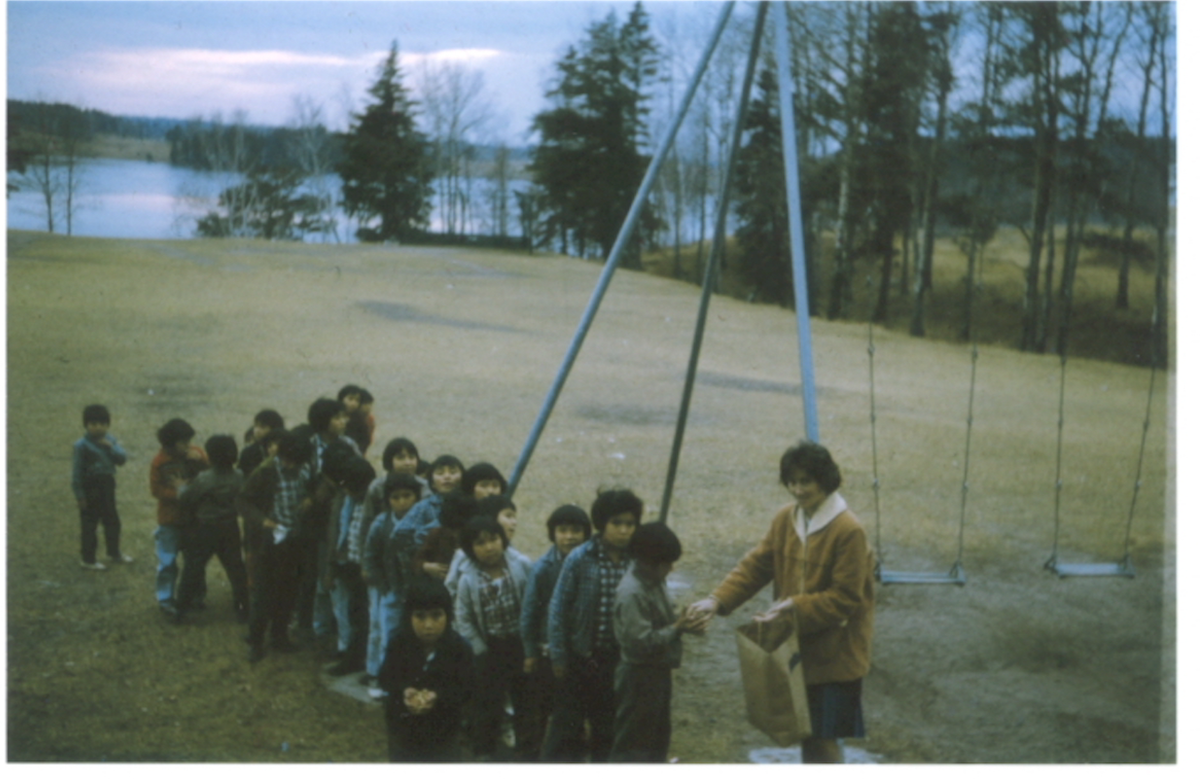

In 1964, Castro created the infamous Military Units to Aid Production (UMAPs), an Orwellian euphemism for the shadowy forced-labor camps where thousands of young people were sent after being caught up in street raids. There, they cut sugar cane from dawn till dusk, likes slaves of yore. Desertion was punishable by prison.

Arenas’ 1969 book, El Mundo Alucinante (published in English as The Ill-Fated Peregrinations of Fray Servando), told the story of a renegade monk from Mexico who dreams of a free society. The political messaging provoked the author’s first big confrontation with the Castro regime, which banned the book. So Arenas had it smuggled abroad, and it was published in France. That “subversive” act, taken together with accusations of homosexuality, led to two years’ imprisonment in the Castillo del Morro prison, a colonial-era Spanish fortress that overlooks Havana’s harbor. Arenas later described the period as singularly nightmarish.

After two suicide attempts, he was allowed to leave prison if he confessed to being (by his later description) a “counter-revolutionary,” publicly disavowed his “ideological weakness,” committed himself to “working for the government, writing optimistic, socialist novels,” and “rehabilitat[ing] himself sexually.” Arenas signed the confession with the intention of fleeing Cuba by any means possible. One night, he tried to swim in the dark to Guantánamo, but was turned back by searchlights and gunfire.

By this time, he’d been erased from Cuban public life. His house had been expropriated by the state, and he couldn’t find a job in a country where the government exerted control over practically every corner of life. Yet it was his literary defenestration that was the most painful of all the punishments. Cuba’s cultural institutions cut ties with him, erasing him from their honor rolls and societies. His former colleagues acted as if he’d never existed—a necessary cruelty if they didn’t want to suffer the same fate.

Then came the mass exodus of 1980, which began after a bus driver and all his passengers sought asylum at the Peruvian embassy in Havana. When word got out that this was a way to get out, nearly 11,000 desperate citizens packed the compound. Eventually, Castro opened the port of Mariel to let the country’s “undesirables” and “anti-socials” flee. It was Arenas’ opportunity to leave the island.

All in all, more than 130,000 set sail on rafts and boats made of rotten wood, house doors, truck tires, and anything else that could float. Some died on the voyage. Others were rescued off Florida by the US Coast Guard. That included Arenas, who’d been adrift for several days without gasoline or food, in the middle of the Gulf of Mexico. The author described that traumatic experience in many of his essays and plays, but never more poignantly than in his 1983 poem Mar (Sea), a memoriam to the victims of the Mariel boatlift:

…Seas of unscrupulous traffickers,

seas of informants posing as swimmers

and teachers trading in crime,

seas of beaches-turned-trenches,

seas of bullet-riddled bodies

that still thunder in our foam-flecked memory.

We don’t have the sea,

but we have the drowned,

we have fingernails, we have sliced-off fingers,

the odd ear or eye the sated shark refused.

We have fingernails…

Arenas went from inner exile to outer exile in a land that many Cubans learned to embrace and call home. Life in the United States brought him safety and freedom, but not joy. “The exile is a person who, having lost a loved one, keeps searching for the face he loves in every new face and, forever deceiving himself, thinks he has found it,” he would later write.

Attacked by left-wing intellectuals for his harsh criticisms of the Cuban regime, and overwhelmed by his diaspora experience, Arenas separated himself from the loud political climate of Miami soon after his arrival. He considered this scene to be a “caricature of Cuba,” and moved to New York to begin a new life. There, he worked to finish his semi-autobiographical Pentagonia, a series of five novels, while also becoming aware that he’d contracted AIDS. Weakened by the disease, he finished his memoirs by dictating into a tape recorder over three years, and then having his words typed by a friend. In 1993, his posthumously published autobiography was named by the New York Times as one of the previous year’s best books. In 2000, Before Night Falls, was adapted into a film of the same name, directed by Julian Schnabel.

Before leaving this world, Arenas left a letter to his English translator, Dolores Koch, in a sealed envelope, describing why he’d chosen to end his life: Due to his failing state, he could no longer “write and fight for the freedom of Cuba,” his two reasons for existence. His last words were: “My message is not one of defeat but of struggle and hope. Cuba will be free. I already am.”

During his short, intensely lived life, Reinaldo Arenas wrote more than 10 books, numerous short stories, plays and poems, and dozens of essays. Among his most outstanding works were The Palace of the White Skunks (1990), The Color of Summer (1982), and Farewell to the Sea (1987). Perhaps no other writer in Cuban history has so vividly rendered the raw post-revolutionary state of repression and solitude that gripped Cuba, nor the numbing loneliness of exile. His legacy defines a unique time in the history of Latin American literature. And as we all seek to come to terms with a newly assertive spirit of ideological conformism and intimidation in our own time, his work helps remind us that a revolutionary dictatorship is still a dictatorship, no matter what flag it flies or what language it speaks.