Affirmative Consent

Bad Vibrations: The Lies Universities Tell Their Students about Sex

Universities are free to promote sexual experimentation. But they should be honest that pushing norms and boundaries involves making mistakes.

Universities today bombard students with two contradictory messages about sex, effectively encouraging them to carry a dildo in their pocket, while lugging a fainting couch behind them.

On the one hand, universities have returned to a quasi-Victorian concern with the unique fragility and vulnerability of college women in matters of sex. This belief in the frailty of college women flows from a lineage of feminist theory, whose foremost representative is probably Catherine MacKinnon, in which “structures of power” hold down women as inherently unequal partners in sex. These structures, the argument goes, must be reformed to correct historical wrongs, to reward and encourage the right sorts of individuals and activities, while punishing and suppressing the wrong ones.

On the other side of the campus sex ledger is the dildo raffle. At “Sex Week” festivities and other gatherings nationwide, colleges and universities actively promote sexual libertinism. During Sex Weeks, campuses routinely host BDSM demonstrations, and rhapsodise over orgasms, anal sex, sex toys, and more. The University of Wisconsin-La Crosse hosted a teach-in entitled “Clitoral Masturbation and Free Vibrator Giveaway.” It is considered repressed and repressive to criticize this cornucopia of carnal delight.

This hearkens back to other feminists of the 1980s, such as Gayle S. Rubin, who railed against “moral panics” and “erotic stigma” as “the last socially respectable form of prejudice,” functioning “in much the same ways as do ideological systems of racism, ethnocentrism, and religious chauvinism.” This makes the dildo a powerful weapon, a literal spear thrust at the prudish soul of bigotry.

What’s less obvious is that the dildo and fainting couch are part of one and the same campus dialogue. To their credit, campus activists want to banish the bad old days, when universities swept sexual assault under the rug, protecting or even aiding and abetting sexual assault in athletic programs. Accordingly, the Ohio State University puts on seminars about sexual violence and assault right alongside programs on “Kink 101” and “Sex Toys 101.”

Monitoring and coordinating this intellectually incoherent movement are the campus student-conduct offices. Through these budget-busting bureaucracies, universities impose byzantine rules regulating students’ sex lives. The message is: test the outer limits of sexuality! But be aware, a hall monitor is always watching!

So what is going on?

Most universities today define sexual assault differently from how it’s specified in law. Colleges now define “sexual assault” so it includes lawful conduct that couldn’t be prosecuted under the criminal law in any state—whether red, blue, or purple. It includes missteps that, in years past, would likely have been considered just messy, “live and learn” encounters between inexperienced (and often inebriated) young people. When pressed, campus administrators justify their new definitions of sexual assault by asserting the right of educational institutions to teach “new values” to the student body. While some judge this an unqualified good, the reality is more complicated.

Certainly, increased awareness of sexual misconduct has made bad behavior less acceptable everywhere, from fraternity parties to boardrooms. And maybe “Sex Weeks” have encouraged more honest discussions among partners—these are no doubt positive developments. If women come away more assertive and more certain about what they want, who could argue with that?

But the redefinition of sexual misconduct, and its enhanced policing by campus administrators, frequently has catastrophic consequences. Students are coming of age in a climate that seeks both to outdo the sexual experimentation of the 1970s and to impose an atmosphere of neo-Victorian surveillance. Campus investigators interrogate inexperienced students not only about whether they had consent for sex, but how they knew they had affirmative consent for each separate act of physical intimacy—each touch, each kiss, each penetration, and each position assumed while performing the latter. The neo-Victorian thus atomizes intimacy into microscopic bits.

Students—particularly those who are socially awkward, sexually inexperienced, or have conditions that impair their understanding of subtle social cues—are routinely punished for conduct they genuinely believed was consensual, but that transgresses new campus rules. This has led to a wave of litigation by students who allege they were wrongly accused: since 2011, more than 600 such lawsuits have been filed.

At the same time, female students—although not exclusively—are advised that encounters they may initially perceive as regrettable but consensual were, in fact, non-consensual “sexual violence.” At Washington & Lee University, for example, the Title IX officer put on a presentation about an article entitled “Is It Possible That There is Something In Between Consensual Sex And Rape… And That It Happens To Almost Every Girl Out There?” In the article itself, the author argues that a large category of legally consensual sex is “rape-ish” (she describes no coercion or violence). Campus sexual misconduct officers take it one step further and redefine regrettable choices—in which women have agency—as acts of “sexual violence” perpetrated against them by another. In these the administration must intervene, discipline, and punish.

This has important psychological ramifications, explains social psychologist Pamela Paresky: “The ability to make choices is how we know we are free, and no free person gets through life without making choices that in hindsight they would make differently. Knowing the difference between making choices and being forced to do things against our will is essential, not only to learning from our mistakes but maintaining psychological integrity and being truly free.”

The campus courts occasioned by this movement have also led to systemic violations of accused students’ due process rights, undermining the integrity of the whole project. Victims can find their cases overturned either on appeal or by a court when the accused sues the university over procedural violations.

Increasingly, plaintiffs, both women and men, are winning. A woman sued the University of Kentucky when it repeatedly botched her disciplinary proceedings by neglecting the rights of the student she accused. This kind of kangaroo court benefits no one, neither the alleged victim nor the accused. The woman finally took the university to court for its deliberate indifference to her serious complaint of sexual assault, and the court held that “the University bungled the disciplinary hearings so badly, so inexcusably, that it necessitated three appeals and reversals in an attempt to remedy the due process deficiencies.” This, it concluded, “profoundly affected [her] ability to obtain an education.”

We think these problems stem, at least in part, from the impossible tension, under the tutelage of campus officialdom, between the dildo and the fainting couch. The history of campus activism in matters of sex suggests a more sensible solution.

University surveillance of the student body has, in some ways, come full circle. The college administrators dissecting the minutiae of students’ sex lives walk in the footsteps of the 19th century administrators of Victorian universities. At that time, the institutions scarcely expected students to be adults, certainly not in matters of sex. Campus sex was prohibited. Students were also forbidden to marry and expelled if they did.

Deans and faculty were substitute parents—in loco parentis. The earliest surviving handbook of Yale College, from 1887, reflects the assumption that students could not behave as adults. It even admonished them to clean their rooms: “students may be excluded whose rooms have been reported to the Faculty for disorder at any time…” Other rules even forbade them from “sit[ting] on the College fence on Sunday”—an apparent red flag of loutishness.

In parallel with contemporary “cancel culture,” the Victorian university proscribed insulting others. Yet the call to be “woke” would doubtless have befuddled bluebloods in the Gilded Age; likewise, the assertion of a civil right in the recognition of personal pronouns, “micro-aggressions,” and many other academic trends loosely associated with identity politics. But 19th century gentlemanly honor codes placed just as much emphasis on validating students’ subjective feelings as would any present-day identitarian code of conduct.

Yale’s code was meant to make these young gentlemen feel safe on campus: “If a student interferes with the personal liberty of a member of another class, or offers him any indignity or insult, he may be permanently separated from his class.” The cardinal rule could be summarized: ACT LIKE A GENTLEMAN! This became Law Number 1, added to a 1901 revision at Yale: “Students will be held accountable for violations of the ordinary rules of good order and gentlemanly conduct, whether the particular acts are specifically forbidden by the College rules or not.”

Unsurprisingly, the colleges of the Victorian era didn’t have many sex rules. They didn’t have to, because most excluded women, and when such rules initially appeared they were straightforward. The first to address women at Yale appeared in 1923: “Ladies may not be entertained in College dormitories except by the written permission of the Dean.” No phalanx of university administrators was needed to enforce rules like this. Women were simply banned.

Even early coed universities had simple rules. At Brandeis University in the 1950s, socializing between male and female students was limited to a few hours per day in common rooms. University regulations even barred fathers and brothers from women’s dormitories—unless they were helping to carry luggage, in which case their presence was announced by a shout of “Man on the hall!”

These rules changed dramatically as sex desegregation hit the campus. But in loco parentis held on in parietal rules, “parietal” meaning literally a “wall” between the sexes, designed to keep students from having sexual intercourse. Campus rulebooks also quadrupled in girth—though modest beside the tomes handed down by campus “judiciaries” today.

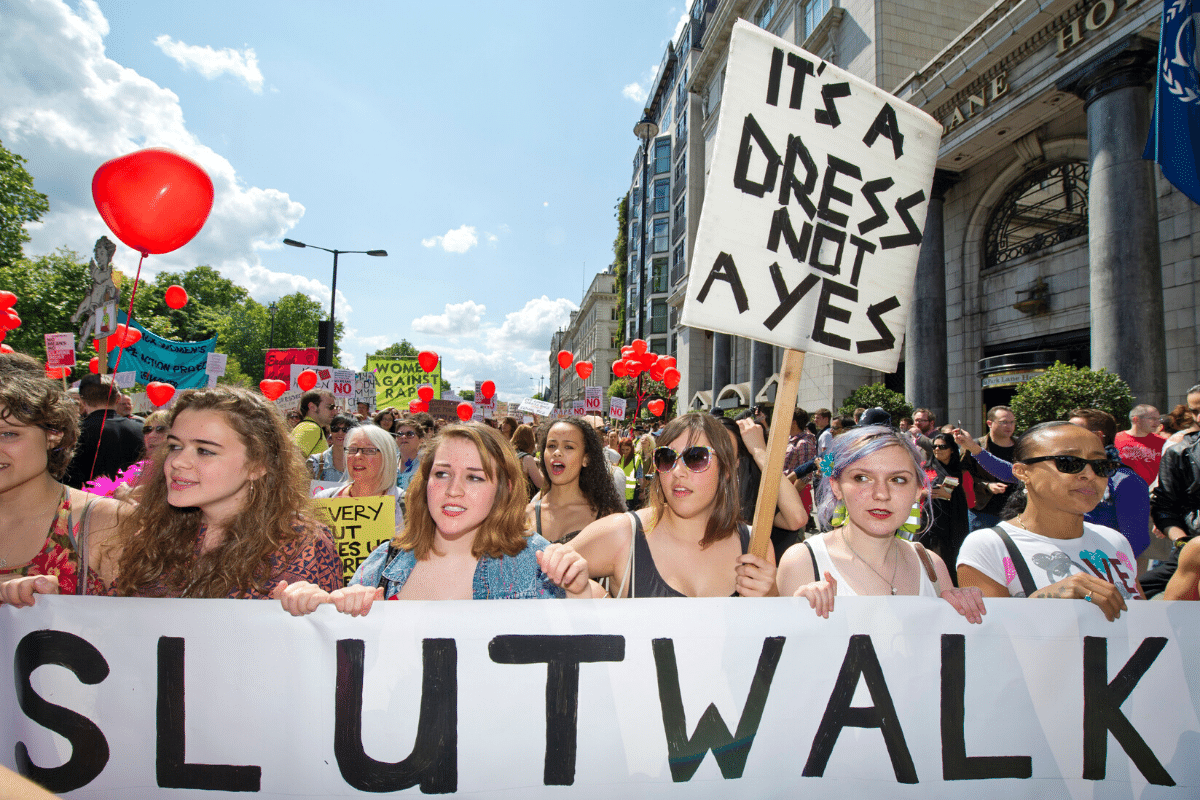

Student activists led the campus co-educational revolution of the 1960s and 1970s to dismantle these regulations. But the movement would be scarcely recognizable to 21st century student demonstrators. Rather than demanding greater regulation, the students of the 60s and 70s bridled against the oversight of their private lives.

At Yale College, Junior Aviam Soifer spearheaded a student committee that pushed for a “Coeducation Week at Yale” in 1968, against Yale’s administration. The students organized the visit of approximately 300 women from women’s colleges to spend a week in the male dormitories of Yale. The presence of 300 female students (as opposed to the numerous working women) was considered so disruptive that the police increased the officers on night patrol.

When Yale finally admitted its first women’s class in fall 1969, protests quickly erupted over administrative obtuseness. President Kingman Brewster, Jr. announced to students that Yale wouldn’t house women in any buildings with men. Students quickly shouted him down and “deplatformed” him. Fearing for his safety, President Brewster preserved himself by speedily capitulating to student demands. Yale distributed its first female class of 250 among the different residential colleges. Even so, there was a separate entrance for them, “with a guard and parietals” in place. The Yale student handbook still strictly controlled “visiting hours” for women.

Despite similarities to contemporary student radicalism, however, there were significant differences. Students largely asserted their freedom from campus bureaucrats’ supervision, rather than asking to be protected. They did not demand ever-more complex restrictions to govern their sex lives, nor call for sensitivity training. They were rejecting, flaunting, and breaking the rules—sometimes daring administrators to do anything about it.

The social upheaval of the late 1960s and 1970s—not to mention the widespread availability of the Pill—transformed sex on campus in ways that became permanent. It’s difficult to imagine any secular American university returning to “open door, one foot on the floor” policies. Yet although premarital sex among students is now the norm, it’s subject to increasingly confusing rules, policed by an ever-expanding campus administration. The pearl-clutching of yesteryear has been replaced by clipboard-clutching bureaucrats.

Where did these rules come from?

Surprisingly, they came from a groundswell of student activism. It wasn’t an overreaching federal government that first imposed them, as critics often complain. In 1991, at the prompting of a group called “Womyn of Antioch,” Antioch College in Ohio adopted a sexual misconduct policy that redefined what it meant to consent. According to the Antioch policy, “[t]he person(s) who initiate(s) the sexual activity is responsible for asking for consent,” and “[t]he person(s) who are asked are responsible for verbally responding.” Not only was verbal consent required, but “[e]ach new level of sexual activity requires consent.” Previously, campus policy focused on whether someone said “no.” Antioch focused, by contrast, on whether someone affirmatively said “yes.” The eventual rule had no fewer than 14 elements defining the unambiguous “Yes.”

An eruption of ridicule greeted these new sex rules in the early 1990s. The idea of requiring verbal permission for each step of sexual activity spawned countless jokes. Saturday Night Live even aired a sketch featuring a quiz show at Antioch called, “Is It Date Rape?”

Over the years, however, the concept of “affirmative consent,” so widely ridiculed back then, became the norm in college sexual misconduct policies. These policies start from the presumption that sex is non-consensual and must be proven otherwise. They also seem to assume that women have little to no sexual agency, or worse, that women are passive victims. A Title IX training slide from Boston University, for example, cites “poor communication” as something that can render sex non-consensual, and thus turn it into sexual violence. An avalanche of lawsuits has brought to light the conduct that the neo-Victorians now condemn.

One former Northwestern University student sued after he was expelled over a sexual encounter in which he supposedly used “‘emotional and verbal coercion,’ apparently because [he] requested sex more than once that evening.” Repeating the request was considered sufficient evidence of coercion, not because the man, turned down, then forced his girlfriend to submit (the school found no evidence of force), but because his request itself was unwanted. Behind the expulsion lies an assumption that the young woman, like her Victorian ancestor on the fainting couch, was too fragile to withstand the verbal overture and bereft of the ability to assert her will and say “No.”

In another case discussed by Hanna Stotland in The New York Times, a male student was expelled because—though it was undisputed the young woman consented to sexual intercourse—the man didn’t desist quickly enough when she began to cry. Her alleged emotional trauma alone was enough to condemn him.

Nor is it always women recast as weaker vessels. At Brandeis University, for example, a student, J.C., charged his ex-boyfriend with sexual misconduct for, among other things, “occasionally wak[ing] him up by kissing him” and “look[ing] at his private areas when they were showering together.” Brandeis’s special examiner determined that “J.C. … was not strong-willed or forceful enough” to stand up to these supposed onslaughts and condemned the ex-boyfriend for “serious sexual transgressions.”

If the groundswell of support for these new campus norms came from below, the apparatus that now enforces them did not. In large part owing to federal regulations and guidance, every university has established a “sex bureaucracy,” justified by the federal law of Title IX, dedicated to policing students’ sex lives.

Passed in 1972, Title IX prohibits sex discrimination at federally funded educational institutions. In the 1990s, courts extended Title IX to include an institution’s deliberate indifference to student-on-student sexual assault and harassment. Thereafter, Title IX enforcement was rapidly institutionalized throughout higher education. Between 2013 and 2016, for example, Title IX spending at UC Berkeley rose by at least $2 million. Similarly, Harvard University in 2016 employed 50 full- and part-time Title IX coordinators across its 13 schools.

All of this sends today’s students a message that is, to put it mildly, mixed: you should enthusiastically embrace sexual freedom and experimentation—but make one misstep, even unintentionally, and you will be branded for life as either a sexual predator or trauma victim. This pathologizes the awkward, messy, unavoidably emotional landscape of youthful sexuality.

Obviously, no one wants to return to the days when simply fraternizing with the opposite sex could get you expelled, nor to a time when colleges looked the other way at sexual assault. But the rules of the Victorian university offered one thing that’s now sorely lacking. And that is clarity.

The world of the dildo and fainting couch offers no clarity whatsoever. If administrators genuinely believe that 25% of the female student body will be sexually assaulted, it would be a lot easier to go back to single-sex dorms and strict parietal rules. Yet it seems illogical simultaneously to encourage unbridled sexual experimentation, but only under the strictest guidelines. Staffing universities with the equivalent of hall monitors, who peer into the most granular details of students’ sex lives, seems a failed social experiment.

We think three things would lead to a more practical approach. They all begin with a simple plea—that universities be honest with students.

First, we agree that universities should be free to set rules to safeguard the educational environment. Potentially, this can embrace new values—like the spectacularly successful co-education movement of the 1960s. Maybe it should include a new dialogue about consent today. But universities should stop telling students that rules about affirmative consent define actual crimes of “sexual violence.” At most, universities administer limited civil infractions. They are not prosecuting crimes. Campus definitions of affirmative consent have been uniformly rejected as criminal law standards. While every sexual assault that could be prosecuted as a crime would meet the definition of sexual assault under campus conduct codes, the reverse is not even remotely true.

If cases really involve sexual violence, they should be addressed by law enforcement. No one wants a world where genuine sexual violence is swept under the rug. But this is what universities do, holding themselves out to students as protectors simply by expelling actual violent offenders—who then return, free and at large, to society. Real criminals of course should go to jail. Yet the sex bureaucrats tell students they are saving them from “sexual violence” and “rape,” implying real crimes, when what they are really doing is punishing students who have violated, not the law, but rather a new set of campus sex norms. Schools also project the message that the Title IX office is a more welcoming place to report “sexual violence” than the criminal justice system. But this sympathetic environment exists—if it does—mostly because the Title IX offices prosecute conduct which isn’t strictly criminal. Universities should be honest about this, too.

Second, they should stop promoting fainting-couch culture. Alleged victims, we’re told, are too traumatized to submit to cross-examination. Really? Women outside the ivory tower didn’t get this memo, nor do witnesses to murder, kidnap victims, or victims of other traumatic crimes. These and similar myths propagate the message that college women are too frail to participate as full adults in civil society, another parallel to the Victorians. Universities should treat college women as strong enough to assert their rights in a free society as equals.

Universities are free to promote sexual experimentation. But they should be honest that pushing norms and boundaries involves making mistakes. It’s the nature of experimentation that there will inevitably be regrets with something so intimate and personal as sex. This, however, should not be quasi-criminalized.

Finally, although universities should have the authority to enforce their own rules, including sexual misconduct, they should be honest about the fact that the values they seek to instil are neither intuitive nor even widely accepted. Instead, universities act as if they have discovered the importance of “consent” for the first time, a concept long established in criminal and civil law. It’s simply understood very differently beyond the ivory tower.

Schools should develop a nomenclature that reflects this fact. If students violate campus rules, schools may punish them. That doesn’t mean students should be expelled as sex offenders. Of course, if the conduct is a real crime, that’s a different story.

If schools want to radically re-define sexual agency, sexual mores, and consent, that’s their prerogative (within legal limits). Maybe they’ll succeed; maybe they won’t. But they shouldn’t create a generation of neo-sex offenders and neo-trauma victims to give birth to this brave new world.