Education

The Fight over Alternative Education

Bartholet’s polemic is by no means simply directed at homeschooling all by itself. It is part of a larger—and relatively recent—specific animus among progressive academics and politicians against a range of alternatives to conventional public schooling

Articles in college alumni magazines, even in the Ivy League, are usually puff pieces about academic programs and professors. They are designed to make graduates feel so good about their alma mater and its intellectual achievements that they will write out yet another donation check. Seldom do the articles circulate much outside of the closed circle of alums. Not so with a 1,007-word piece in the May – June 2020 issue of the Harvard Magazineentitled “The Risks of Homeschooling” in which Harvard Law School professor Elizabeth Bartholet recommended a “presumptive ban” against parents’ educating their children at home (as between three and four percent of US parents currently do). That is, unless these parents can prove to educational authorities “that their case is justified.”

Bartholet had already expressed this view in an extensively footnoted 80-page scholarly article for the Arizona Law Review entitled “Homeschooling: Parent Right Absolutism vs. Child Rights to Education & Protection” published earlier in 2020. There, she wrote:

A very large proportion of homeschooling parents are ideologically committed to isolating their children from the majority culture and indoctrinating them in views and values that are in serious conflict with that culture. Some believe that women should be subservient to men; others believe that race stamps some people as inferior to others. Many don’t believe in the scientific method, looking to the Bible instead as their source for understanding the world.

To shore up her position, Bartholet recited a litany of horror stories that sound more like failures of social service bureaucracy than failures of homeschooling per se: Author Tara Westover, whose 2018 bestseller, Educated, recounted that her breakaway-Mormon survivalist father in Idaho had taught her to read but little else; and seven-year-old Adrian Jones, starved, tortured, and killed by his father and stepmother in Kansas in 2015, then fed to pigs. (Both adults, who claimed to be homeschooling the boy, are serving life sentences for murder.) Armed with anecdotes like these, Bartholet called for a “new legal regime” of “positive rights” that would protect “child rights to an education allowing them to exercise autonomy rights in their future lives, including rights to make meaningful career and lifestyle choices.”

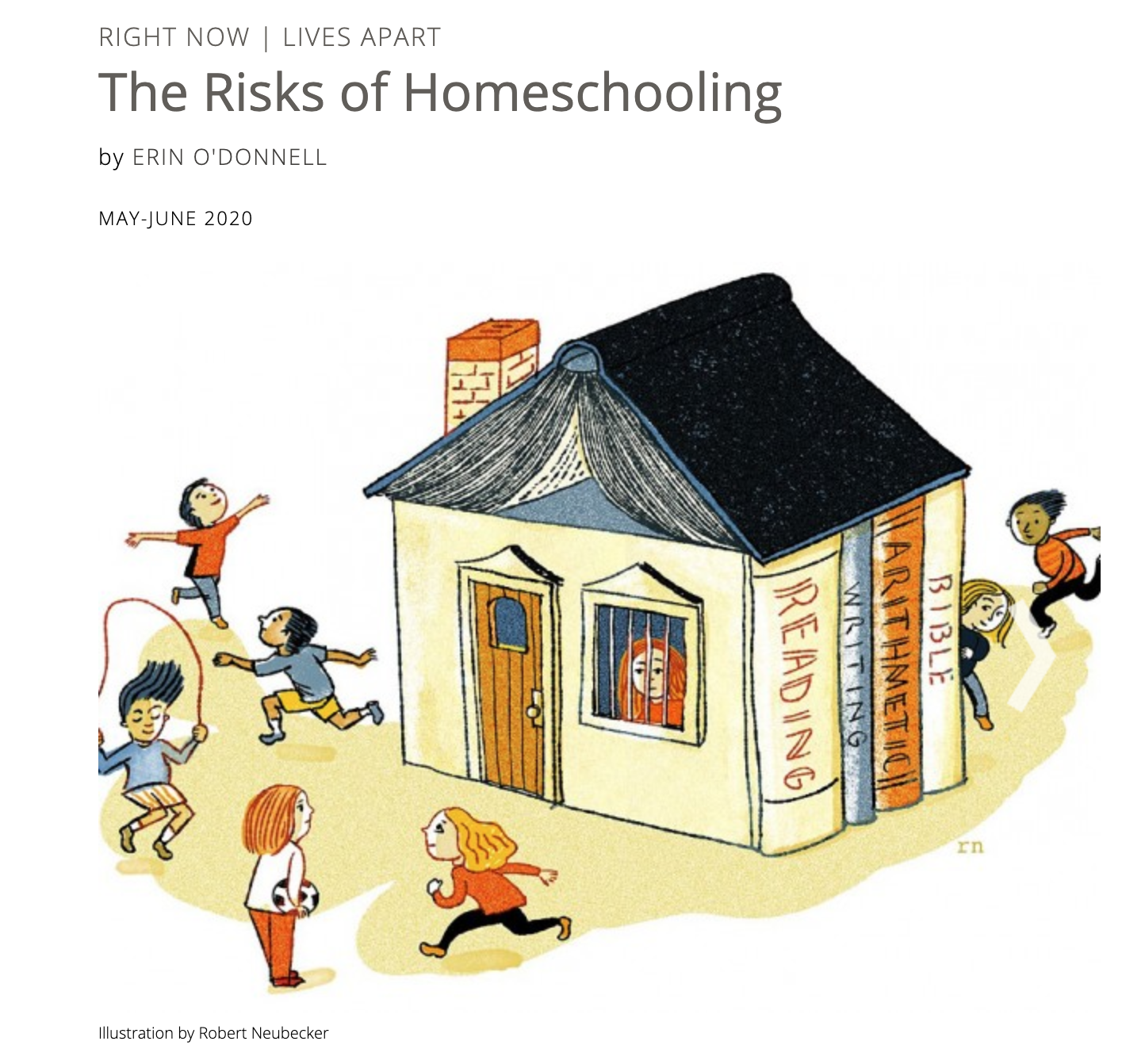

In both articles, Bartholet trained her sights specifically on Christianity, asserting that conservative Christian beliefs lay behind the decisions of “up to 90 percent” of homeschooling parents to “seek to remove their children from mainstream culture.” Indeed, her Arizona Law Review article and its footnotes employ the words “Bible” and “Christian” a total of 18 times, all negatively (along with a footnote or two excoriating Hasidic Jewish yeshivas and their near-exclusive focus on Talmudic studies). In her Arizona Law Review article Bartholet proposed that homeschooling parents who manage to overcome all the administrative hurdles she demands be further required to submit their curricula to state authorities for advance approval and agree to twice-yearly government visits to their home. The Harvard Magazine illustration alone seems designed to confirm the worst fears of aggressively secularized Harvard graduates (including, probably, many of Bartholet’s Harvard Law colleagues) while inflaming homeschooling parents: children frolicking and jumping rope outdoors while a sad little girl is imprisoned inside a house made out of books titled “Reading,” “Writing,” “Arithmetic,” and “Bible.”

(The illustration in the print edition of the Harvard Magazine misspells the title on the spine of the third book as “Arithmatic.” The magazine quickly corrected the mistake in its online edition, but the lucky Harvard grads who received the print magazine might well own their own version of the famously mangled 1918 “upside-down airplane” US postage stamp that has sold at auction for close to $1 million.)

So pervasive was the negative reaction to the Harvard Magazine interview with Bartholet that the magazine shut down its comments section after only nine comments, all of which were scathing and at least one of which was left by a self-proclaimed atheist who had homeschooled her children for eight years. The law school had organized a closed-to-the-public, invitation-only conference scheduled for June 18th – 19th to discuss the “problems, politics, and prospects for reform” of homeschooling, but this was postponed until at least 2021 following the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic. The conference’s sponsors were to have been Bartholet and James G. Dwyer, a professor at the William and Mary Law School known for his acerbic critiques of parental rights in education. The planned list of speakers included other academics generally critical of homeschooling, plus several representatives of the Coalition for Responsible Home Education, a nonprofit dedicated to homeschooling “reform” whose website consists largely of narratives of the unhappy experiences of homeschool graduates.

But Bartholet’s polemic is by no means simply directed at homeschooling all by itself. It is part of a larger—and relatively recent—specific animus among progressive academics and politicians against a range of alternatives to conventional public schooling: religious and other private schools, and even charter schools, which are government-funded but independent in curricula, governance, and teacher hiring (43 states plus the District of Columbia allow for these publicly funded but privately operated institutions). Charter schools enroll about three million children nationwide, most of whom live in failing urban public-school districts where charters seem to promise stricter discipline and more focused academic programs. Throughout the 1990s and the 2010s, they had been endorsed by Democratic politicians, including former California governor Jerry Brown and Presidents Bill Clinton and Barack Obama.

In 2019, however, left-leaning Democratic presidential candidates Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren both vowed to abolish charter schools if elected, and this position has also been adopted by self-proclaimed moderate and presumptive nominee Joe Biden, who served as Obama’s vice president. In 1997, when Biden was a Delaware senator, he delivered a speech in which he not only threw his support behind charters but also endorsed “voucher” programs through which governments help to pay for underprivileged children to be taught at Catholic parochial and other private schools. “Is it not possible,” he asked from the floor of the Senate, “that giving poor kids a way out will force the public schools to improve and result in more people coming back?”

But by December 2019, Biden was pledging that not only voucher programs but also charter schools themselves (both of which are promoted by GOP President Trump’s education secretary, Betsy DeVos) would “be gone” if he were elected. Perhaps he was merely securing the endorsement of public school teachers’ unions—which he duly received—but the turnabout was dramatic nonetheless. An equally dramatic reversal occurred in Jerry Brown’s California, where 10 percent of school-age children attend some 1,300 charters. In the fall of 2019, the California legislature passed—and Brown’s Democratic successor Gov. Gavin Newsom signed—a law that gives public school districts vastly increased power to decide whether to approve new charter schools or renew the charters of existing schools. Furthermore, all teachers hired by charter schools, not just those teaching such “core” subjects as math and language arts, will have to be state-accredited—that is, they will have to go through the state education-school regime: no more music teachers whose only qualification is a degree from Julliard. The legislation was supported by teachers’ unions but also by the California Charter Schools Association, which viewed the new law as a compromise in the face of a possible ban on charter schools altogether.

In her Arizona Law Review article, the eye Bartholet cast upon public-school alternatives was almost as cold as that she cast upon homeschoolers who eschew every form of organized schooling:

Some private schools pose problems of the same nature as homeschooling. Religious and other groups with views and values far outside the mainstream operate private schools with very little regulation ensuring that children receive adequate educations or exposure to alternative perspectives. Policymakers should impose greater restrictions on private schools for many of the same reasons that they should restrict homeschooling. Moreover, it would be deeply unfair to allow those who can afford private schools to isolate their children from public values in private schools reflecting the parents’ values, while denying this possibility to those unable to afford such schools.

“Views and values far outside the mainstream,” “exposure to alternative perspectives,” “isolate their children,” and “schools reflecting their parents’ values” are the operative terms here. Underlying them seems to be the assumption that the main purpose of education isn’t to teach young people reading, writing, and arithmetic but to instill—or at least “expose” them to—certain “views,” “values,” and “perspectives.” It is equally important that those “views and values” be “mainstream”—which seem to be the fashionable preoccupations of the liberal professoriate: feminism, LGBTQ issues, global warming, racial oppression, and “diversity” of every variety except the ideological kind.

It is worth noting, for example, that several major public school districts—in Boston, New York, and Washington, D.C., among other cities—either actively encouraged or promised leniency to students who skipped classes on September 20th, 2019, to join a “global strike” demanding government action on “climate change.” Astonishingly, some 3,500 public schools peremptorily adopted the New York Times’s controversial but Pulitzer Prize-winning “1619 Project” magazine special into their curricula, even though its historical accuracy was vehemently contested by many academic historians. Are we to assume that this is what is meant by the “mainstream” in the world of public education?

Nor is Bartholet alone. The academics scheduled to deliver papers at the postponed conference all teach at prestigious institutions, and a survey of their writings indicates that what they most fear is that children will be taught things that are ideologically wrong. James Dwyer, the conference’s co-sponsor, wrote in a 2016 scholarly article: “Perhaps one day feminists will take a serious interest in the subordinating indoctrination to which girls are subjected in many religious schools and home schools.” Conference participant Michael A. Rebell, a lawyer with joint appointments at Columbia Law School and Columbia Teachers College, wrote in his 2018 book, Flunking Democracy: Schools, Courts, and Civic Participation, that many parents who send their children to alternative schools believe that “exposing their children to ideas such as secularism, atheism, feminism, and value relativism is inconsistent with the values they espouse and undermines their ability to inculcate in their children their beliefs in the sacred, absolute truth of the Bible.”

In a 2005 essay entitled “Why Homeschooling Should be Regulated,” Stanford political science professor Rob Reich wrote: “With little or no exposure to competing ideas or interaction with people whose convictions are different from their parents’, children who are home schooled can be raised in an all-encompassing or total environment that fails to develop their capacity to think for themselves. To put this in language commonly used by political theorists, the capacity of children to ‘exit’ their parents’ way of life is undermined and they run the risk of becoming ‘ethically servile.’” And in a 2010 article entitled “Parent As (Mere) Educational Trustee: Whose Education Is It Anyway?,” Georgetown law professor Jeffrey Shulman wrote: “[T]he parent’s right to educate his or her children is strictly circumscribed by the parent’s duty to ensure that children learn habits of critical reasoning and reflection… [C]ourts should look with skepticism at any educational program—whether imposed by the parent or by the state—that, by restricting the spectrum of available knowledge, fails to prepare the child for obligations beyond those of familial obedience.”

The notion that parents and the schools they choose for their offspring are obligated to provide an “exit” strategy from the principles that the parents and schools hold most dear, and to expose them to ideas that they find morally or philosophically repugnant, may seem surprising to people who believe that the function of schools is actually to teach the multiplication tables and how to spell. Or that learning how to research and write a coherent essay ought to supply enough training in “critical reasoning and reflection” without religiously conservative parents or the schools they choose being required to rehearse the arguments in favor of unrestricted abortion, letting biological males use women’s bathrooms, the “1619 Project,” or why belief in God may be bunk.

However, at least some advocates of content-based regulation for alternative schooling seem far more accommodating toward religious and other kinds of conservatives in one-to-one conversation than they appear in their scholarship. While the Harvard Law School did not respond to my request for an interview with Elizabeth Bartholet (unlike other Harvard Law faculty members, she has no office email address listed online for direct contact), and James Dwyer refused to grant an interview unless I read a book he had written that was, practically speaking, unavailable during the coronavirus pandemic, Stanford’s Rob Reich told me over the phone that he was simply distinguishing between the views, religious and otherwise, that parents are entitled to convey to their children as parents and the accurate information that parents as teachers should be required to convey when covering an academic subject.

For example, evangelical parents may believe that abortion is morally wrong, Reich said, but they should be obliged to explain the current legal status of abortion and that people of differing views on abortion are all equal citizens. “They may believe that the Bible instructs different roles for men and women,” Reich said. “They can teach what they believe is women’s appropriate role, but they can’t then say that there’s no need to teach girls high school-level science.” Although an advocate for education regulation, Reich seems to take a minimalist approach: occasional standardized testing in core subjects in order to ensure that homeschoolers are learning something substantive and aren’t simply being kept at home. He expressed concern that I might want to “tie” him to Elizabeth Bartholet’s “mast” of presumptive condemnation.

The theory that education by its very nature has an ideological component—facilitating children in escaping from their parents’ culture in the name of attaining personal autonomy—goes hand-in-hand with another goal of the anti-alternative education crowd: establishing a “fundamental” constitutional right of children to an education that would grant to federal courts the power to supervise school funding and curricula. Such a right is not specifically enumerated in the US Constitution (although nearly all state constitutions enshrine a governmental duty to provide adequate schooling), and the US Supreme Court has yet to recognize it, despite nearly 50 years of litigation by activist lawyers. The high court has only rarely recognized non-enumerated rights under a general theory of “substantive due process” said to be enshrined in the 14th Amendment; one example is the court’s 2015 decision in Obergefell vs. Hodges declaring a fundamental right to same-sex marriage “implicit in the context of ordered liberty” that the 14th Amendment’s due process clause presumably protects.

Despite the Supreme Court’s half-century of reluctance to extend this concept to education, various justices have issued enough statements in their education opinions over the years—typically involving claims of unequal racial or ethnic treatment, a violation of the 14th Amendment’s equal protection clause, to provide intellectual gruel for those who argue that the purpose of education relates to preserving “ordered liberty” and thus consists of something more than the acquisition of substantive learning. In Brown vs. Board of Education, the landmark 1954 decision striking down racially segregated school systems as denying equal protection of the law to African-Americans, the Supreme Court declared that education “is the very foundation of good citizenship… [I]t is a principal instrument in awakening the child to cultural values, in preparing him for later professional training, and in helping him to adjust normally to his environment.” In Plyler vs. Doe, a 1982 decision again invoking the equal protection clause to rule that public schools could not exclude the children of illegal immigrants, the Supreme Court said: “By denying these children a basic education, we deny them the ability to live within the structure of our civic institutions, and foreclose any realistic possibility that they will contribute in even the smallest way to the progress of our Nation.”

Lawyers and law professors have seized upon these dicta about preparation for citizenship to try one more time to convince the federal courts (and ultimately the Supreme Court) that establishing a “fundamental right” to an education is the most effective way to secure that goal, through judicial oversight of the educational process. And in fact, one federal appellate court, the Cincinnati-based Sixth US Circuit Court of Appeals that encompasses several Midwestern states, ruled exactly that in a 2 – 1 decision, Gary B. vs. Whitmer, on April 23rd, establishing a right to a “basic minimum education, meaning one that provides a chance at foundational literacy” so as to be able to participate in the democratic process. The case involved alleged severe deficiencies in the public-school system in notoriously depopulated and dysfunctional Detroit: crumbling school buildings, malfunctioning heating and cooling systems that exposed children to extremes of heat and cold, vermin-infested classrooms, filthy bathrooms, and such unattractive conditions for teachers that chronic teacher vacancies led to student-overcrowding and miserable results on standardized tests. At one Detroit elementary school only 4.2 percent of third-graders allegedly scored “proficient or above” in English, compared with 46.0 percent overall in the state of Michigan. In one Detroit ninth-grade classroom students allegedly struggled to read at the third-grade level. US Circuit Judge Eric L Clay, author of the majority opinion in Gary B., had no trouble aligning those alleged deficiencies with a finding that a right to a basic minimum education is indeed “implicit in the concept of ordered liberty.” That right, Clay wrote, “is fundamental because it is necessary for even the most limited participation in our country’s democracy.”

The Sixth Circuit’s expansive decision in Gary B. would seem to be inevitably headed to the Supreme Court—except that Michigan’s Democratic governor, Gretchen Whitmer, and Democratic attorney general, Dana Nessel, are both liberal and so unlikely to appeal a ruling, the practical effect of which is likely to force massive state spending to try to repair Detroit’s broken public school system. Furthermore, the ruling has given new impetus to a 1918 federal lawsuit, Cook vs. Raimondo, challenging alleged deficiencies in the public school system throughout the state of Rhode Island. The lead lawyer on that case is Michael Rebell of Columbia, one of Elizabeth Bartholet’s handpicked conference panelists. The Cook suit, which is still in its procedurally preliminary stages, takes Gary B. a step further to try to secure a ruling that a “fundamental” right to an education under the US Constitution extends well beyond minimum literacy and focuses specifically on Rhode Island’s alleged failure to provide enough adequate grounding in civics education to prepare young people “to function productively as civic participants capable of voting, serving on a jury, understanding economic, social, and political systems sufficiently to make informed choices, and to participate effectively in civic activities,” according to the plaintiffs’ complaint. In a phone interview, Rebell made it clear that the ultimate aim of the Cook suit is to set nationwide standards for adequate training in those components of democratic participation. “There’s been a marked decline in the teaching of civics in American public schools,” he said.

Rebell’s observations are certainly supported by the data. Results released in April from the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) civics assessment indicated that less than one-fourth of US eighth-graders in 2018 demonstrated proficiency or more in civics and American history. A 2017 Annenberg Public Policy survey found that only 26 percent of Americans can name the three branches of government and 37 percent can’t name a single right protected by the First Amendment. But Rebell’s notion of what constitutes adequate civics education goes well beyond imparting such textbook information such as how a bill becomes a law or the contents of the Constitution. “Civics knowledge means field trips to legislatures, it means learning democratic values, it means having civil conversations with people having very different views from yours,” he said. “Kids have a right to more than what they’re getting now.”

This experiential aspect of civics education promoted by Rebell—hinging as much on exposure to values (the “very different views” of other people) as on substantive learning—segues nicely with Elizabeth Bartholet’s insistence in her Arizona Law Review article that a “new legal regime” must be put into place to ensure an education that furthers “child rights.” Indeed, Bartholet seems to recognize that such a “new legal regime” might be unpopular with the millions of US voters who choose alternative forms of education for their children, so she calls on the courts to act instead by reinterpreting federal and state constitutions: “Constitutional doctrine should recognize that children have enforceable rights to an appropriate education and to protection against maltreatment. This would mean that legislatures could be required to enact legislation protecting those rights.”

There is an obvious irony here: The two legal cases on which those who pin their hopes for stringently regulating private education both deal with alleged gross inadequacies in public school education. And those inadequacies are even better documented than the failings of some charter schools or the fact that some homeschooling parents belong to eccentric religious sects. The most recent NAEP testing results, for example, indicate that only 37 percent of America’s children rate as proficient or higher in reading and 25 percent as proficient or higher in mathematics—the two most basic educational skills—by the time they reach 12th grade. (This may be the reason why polls show that black and Hispanic Democrats, who often live in the worst-performing public school districts, have not been enthusiastic supporters of the anti-charter school turn among white Democratic politicians; a 2019 New York Times article reported a sharp pro- and con-divide on charters between minority and white Democrats.) Nonetheless, in almost all the rhetoric against homeschooling or religious schooling or charter schooling there is a romanticizing of public schools as versions of Plato’s Academy for youngsters. “There’s a tendency of critics to idealize that which they wish to defend,” said Stanford’s Rob Reich.

Most troubling, though, is the apparent desire of the anti-alternative education faction to shove all children in America into a monolithic system of public schooling, or at the very least, to force those who teach them to adopt a monolithic public school model for education. That model would be replete with whatever pedagogic fads—“everyday” math, “whole word” reading—may be responsible for American children’s generally poor academic performance these days. Worse, it would include a range of secular ideologies to which children are required to be “exposed” that claim to be “mainstream” but are often as insular, as hostile to opposing viewpoints, and as “totalizing” (to use one of Reich’s words) as those of the most fanatical Christians. “I’m not particularly religious, but the anti-religious bias is so thick you can cut it with a knife,” said New York University law professor Richard A. Epstein, an outspoken critic of the “positive rights” jurisprudence that marked both Bartholet’s article and the Gary B. decision. “What they want to do is give the state complete monopoly powers over education.”