How We Live Next

The Age of the Homebody Has Only Begun

The bar for opening the door and going outside is simply going to be set much higher.

The day we’ll all finally be able to safely leave our houses and apartments will also be the day we’ll no longer need to. That’s because the global lockdowns and social-distancing requirements imposed to arrest the spread of COVID-19 have dramatically accelerated the process of making nearly every possible good or service available at our homes.

We now have available to us more home entertainment options, and of a higher quality, than ever before. With so many top cultural institutions making their performances available to all online, aficionados are growing accustomed to watching the best live performances—from pop stars performing in pyjamas all the way up to opera and ballet—from the comfort of viewers’ own homes. If anything, people lament not having sufficient time to watch all of these excellent offerings.

Many of us have been forced to homeschool our children. In doing so, some of us have been realizing a parenting fantasy or living a parenting nightmare, or both. Either way, we’ve become aware of the many ways in which teaching and learning can take place at home. Even many adults have had time to pursue the wealth of excellent learning materials available for free or limited cost—including classes and lectures from the world’s best universities.

Those among us who are teachers or professors were forced to suddenly adapt to online teaching, even if it hadn’t been part of our professional regimen previously. Content migration processes that were expected to take years, if not decades, have been condensed into a few months or weeks. Maybe some of us have found this new way of teaching quite useful, and even, as one professor at a top university recently confessed to me, more productive. Online courses, language apps and just about anything that can be learned through a computer screen, from cooking to computing, are experiencing a global boom.

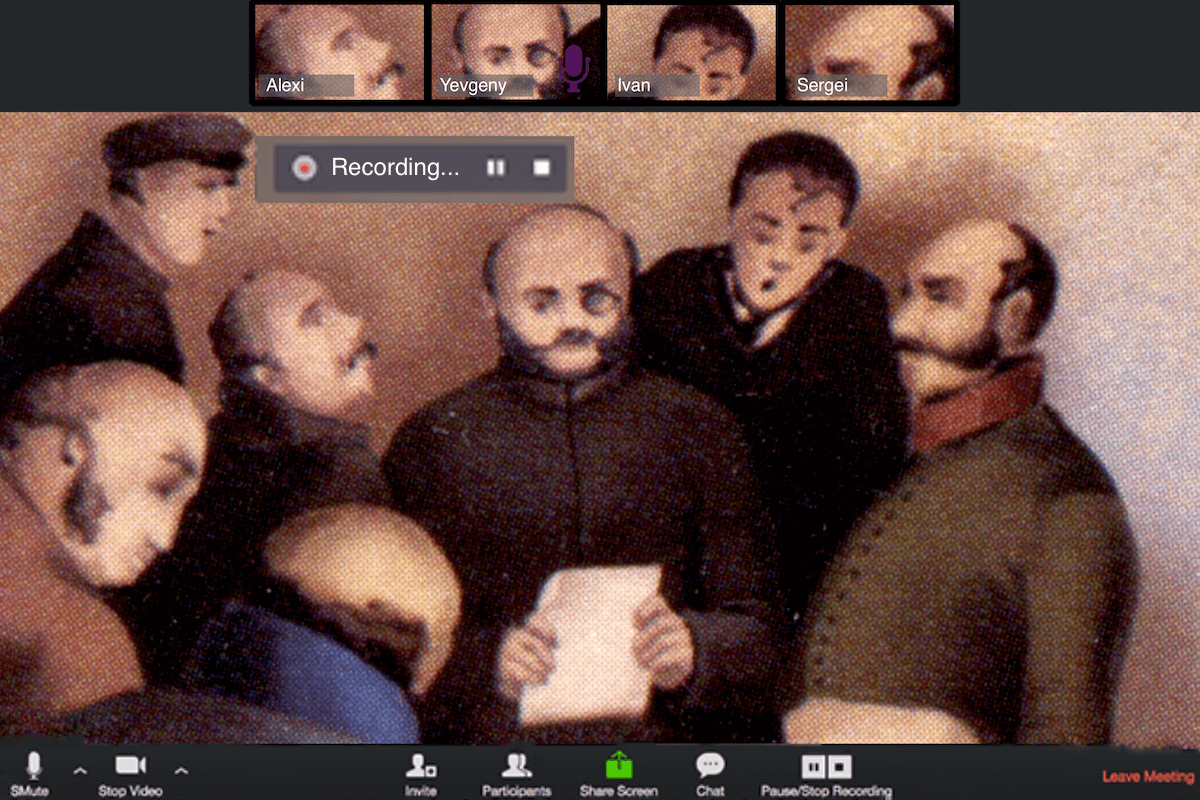

The supermom trying to do it all—preparing dinner while supervising homework while managing a conference call and emptying her inbox: She now has become, by necessity, the standard in many households. Whether submitting reports, briefing colleagues, managing teams (or being managed), updating content or liaising with clients, many of us are now working from home. It’s too early to assess the overall effect on productivity, which will differ greatly based on one’s industry, organization and personality in any case. But so far, all of my friends working from home have testified to the greater effectiveness of Zoom meetings compared with the in-person, office-based variety. Those who do not also have to homeschool in parallel seem to find that productivity can go up when daily travel time is taken out of the equation.

Healthcare, too, is going through an accelerated process of digitization. As non-COVID-19 patients avoid going to doctors and hospitals for non-urgent needs, they’re growing increasingly accustomed to using digital health services—speaking to their doctors on video, getting advice and receiving prescriptions electronically (in some cases, even having medicines delivered at home). All this is done without the need to expose themselves or others to sickness.

Beyond healthcare, the entire digital wellness industry is booming. As the Economist recently noted, meditation apps, digital fitness classes and online cookery courses are gaining millions more subscribers, “with kettlebells and yoga mats selling like toilet paper.” Those who made fun of that sexist Peloton ad in December now find themselves wishing they had one of those same networked exercise bikes to keep fit.

Religion, too, has been forced to change with the times. In late March, the Pope led services alone at the Vatican, the Via Delarosa being abandoned on Easter. Haredi Jews are praying alone in enclosed balconies. And the Kaaba in Mecca is bereft of pilgrims.

Even the lumbering machinery of government has been forced into an accelerated process of digitization. With millions registering for unemployment benefits and newly minted COVID-19 relief programs, governments must scramble to get money into people’s hands before evictions and bankruptcies cripple their economies. New York City is even allowing digital registration for marriage licenses. And City Hall is providing electronic wedding services. Digital elections, once seen as an experimental rarity, may soon become the norm.

The activities that are most reliant on mass congregation—traditional religious services, music concerts, major sports events—are also the ones that will take the longest to go “back to normal,” since these are the activities that, absent a vaccine, can put the greatest number of people at risk. Churches will increasingly have digital congregants, just as major sports leagues may play out whole seasons with no one in the stands. In the long term, even some of the men and women who deliver goods to us may be able to do their jobs through drones.

And so the question will increasingly become: If we will no longer need to leave our homes, what are the purposes for which we will want to leave our homes? The bar for opening the door and going outside is simply going to be set much higher.

The very idea of our home as a sort of base from which we emerge into the world every day will increasingly become obsolete. For many, a new presumption will emerge whereby staying at home is the daily default. And those who do need to leave the house every day, because they are, say, cooks, personal care workers, hospital orderlies and the like, may eventually be able to command fairer wages or even salary premiums.

In the pre-COVID-19 world, the ability to work from home on certain days was something you negotiated with your employer. In the post-COVID-19 world, it will be the opposite: Many jobs will come with the baseline expectation of the home as the default workplace, and the prospective employer will be required to negotiate if she requires you to come to an office or some other work location. Certainly, the last two months have made it difficult for many employers to argue that one’s physical presence in their own office environment is truly necessary.

Currently, K-12 schools provide several services: mass babysitting, socialization, and, of course, actual learning. There has traditionally been value in the bundling together of these services. But the perceived value has decreased now that many parents have discovered during these homeschooling months that at least some actual learning can take place effectively in the home. They will then ask themselves whether and how they want the schools to continue providing the other two services—and, if so, if they want them to provide them in the same way.

In some cases, the services might be unbundled. Some parents might want their children to have personal sessions with a teacher, either at home or at a different physical space, according to some agreed upon schedule; and then have the socializing and babysitting provided in a different manner. The line between school, extracurricular activities, and camp might blur in some cases, as different families focus on a different mix of academic learning, physical conditioning, ethno-cultural knowledge, and life skills.

The idea of schools operating at set hours with set age-based classes might increasingly seem anachronistic. As more actual learning takes place at home, using methods that require students to advance by clearing educational thresholds, it will make less sense to group kids together rigidly according to the date of their birth. More children will work individually or in small groups under the guidance of teachers based on their skill level, rather than their age. The socializing aspect, whether it comes in the form of religious instruction, regional cultural programs, or informal forms of peer-group immersion, might be provided through other means.

Colleges and universities, too, will find that their functions and services are becoming unbundled. In recent years, researchers have noted that much of the value of a diploma from prestigious universities originates not in the actual academic content of the course work, but the networking opportunities and prestige factor associated with the diploma. As Ivy League content becomes a mass-consumed digital product, the monetization of the less tangible social and reputational aspects will become more explicit.

One of the most valuable services we’ll all seek is curated, high-quality social encounters. Chance social encounters already have become more rare in recent years due to smartphones and earbuds, which allow us to remain entertained and stimulated in public spaces without having interactions with others. Being based at home will reduce our work encounters as well. But the desire for human contact will remain unchanged. And so the idea of curated social encounters will extend from its current niches in luxury networking conferences and the like, and increasingly become the norm by which we make new friends and acquaintances.

The human need to breathe fresh air, hear the lap of waves upon the shore and feel the sun will remain as strong as ever. Indeed, it may become stronger, since routine exposure to the elements will no longer be hardwired into daily routines. The importance of recreational access to nature will become a more pressing social issue. And question about who controls nature, and our equality of access thereto, will become a larger part of our politics.

In the long term, the repercussions will be enormous and unpredictable. What will it mean for gender relations, for instance, when more men work from home? Will it serve to further equalize the status of men and women, as both establish themselves equally in the home—or will our roles become stratified in new ways? Or will both men and women benefit from the renewed emphasis on the nuclear unit, as parents both work and educate at home while enjoying more family meals together?

As investments, our homes will become even more important than they are today. In particular, we will invest more in the technological infrastructures of our homes, and in every aspect of comfort and productivity. Even small apartments will become more dense with gadgets for entertainment, work, education, athletics, cooking, and gardening. Some of this will be financed with the money we now spend on cars, meals out, and expensive clothes. Demand for all of these will go down.

In pastoral societies, few people worked exclusively indoors, since you can’t raise crops from your bedroom. During the Industrial Revolution, many field workers took jobs in factories, living in cramped, impersonal dormitories or rooming houses. What we are now observing is an acceleration of the process by which we are creating a new, more private indoor ecology. With the pandemic still raging, it is natural that we now long for the day when we’ll be allowed to leave our homes. But in coming years, once that original sense of relief ebbs, we’ll increasingly ask ourselves why leaving was ever necessary.