Books

The War of Return—A Review

The War of Return is an important book and, unquestionably, a welcome corrective to the plethora of myths, lies, and misconceptions that litter the discourse on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

A review of The War of Return by Adi Schwartz and Einat Wilf, All Points Books (April 2020) 304 pages

In a story that may be apocryphal, the late Christopher Hitchens claimed that he had once seen legendary Israeli diplomat Abba Eban comment that the most striking aspect of the Israeli-Arab conflict is how easily it can be solved: It is simply a matter of dividing the land of Israel into a Jewish state and an Arab state. The only thing standing in the way of this solution is the intense religious or nationalist attachment of both sides to the idea of an undivided nation between the River Jordan and the Mediterranean Sea. Indeed, this assumption that partition alone can bring peace has been the foundation of all of the international community’s peace efforts since the 1967 Six Day War. The only difficulty, it is believed, is persuading the two sides to agree to it.

Not so, argue former Israeli Knesset Member Einat Wilf and journalist Adi Schwartz in their new book The War of Return. What actually lies at the heart of the conflict, they say, is the Palestinian assertion of a “right of return.” Hundreds of thousands of Arabs fled or were expelled from what became the State of Israel after its War of Independence, and the persistent demand that they and their descendants be allowed to return constitutes a refusal to accept a Jewish state on any part of the former mandate. For decades, the Palestinian national movement has insisted on the return of the Arab refugees, and for just as long, Israel has seen this demand as an existential threat that would immediately turn Israel into an Arab state by sheer weight of demographics. And it is this, Wilf and Schwartz say, that has rendered all peace initiatives futile. As Henry Kissinger once said, the minimum concessions that the Arabs demand are greater than the maximum Israel is willing to concede.

“Our research revealed that the Palestinian refugee issue is not just one more issue in the conflict; it is probably the issue,” Wilf and Schwartz assert. “The Palestinian conception of themselves as ‘refugees from Palestine,’ and their demand to exercise a so-called right of return, reflect the Palestinians’ most profound beliefs about their relationship with the land and their willingness or lack thereof to share any part of it with Jews.” As such, they say, the refugee issue has become “a nearly insurmountable obstacle to peace.”

In The War of Return, Wilf and Schwartz trace the convoluted history of the refugee issue and its centrality to Palestinian nationalist ideology, from its origins in 1948 through decades of war and peace efforts to the current stalemate between the two parties to the conflict. Along the way, they reveal much that has been misrepresented, deliberately concealed, and often consciously distorted throughout the long struggle over this tiny piece of emotionally fraught real estate. Presented with such evidence, and despite some innovative suggestions as to a solution, their conclusions, while often revelatory and convincing, are regrettably more than a little depressing.

I. The 1948 Palestinian exodus

Wilf and Schwartz’s comprehensive history of the refugee issue begins with the UN’s adoption in November 1947 of a plan to partition British Mandatory Palestine into an Arab state and a slightly smaller Jewish state. Violence erupted shortly after, and once the British left the territory, hostilities escalated into a full-scale war, during which fighting between the Zionist movement’s Haganah defense force and various Palestinian Arab militias was followed by an invasion by the surrounding Arab countries. Israel prevailed with truncated borders, but the Arab world remained steadfastly committed to the new state’s elimination. Refugees are a byproduct of every military conflict, but the exodus of the Palestinian Arabs would have uniquely consequential ramifications that continue to haunt the conflict and thwart its resolution to this day.

It is now fashionable for historians sympathetic to the Palestinian narrative to downplay the threat that the Jewish community in Mandatory Palestine—the Yishuv—faced in the 1948 conflict. Wilf and Schwartz show conclusively that such attempts, be they sincere or dishonest, are simply untrue. The secretary-general of the Arab League, they note, openly stated that the war was intended to be genocidal, saying, “This will be a war of extermination and momentous massacre, which will be spoken of like the Mongolian massacre and the Crusades.” Meanwhile, the Palestinian Arabs’ most influential leader, the Nazi collaborator Mufti Hajj Amin al-Husseini, said the Arabs would “continue to fight until the Zionists are eliminated, and the whole of Palestine is a purely Arab state.”

Correctly believing that their individual and collective existence were threatened, the Zionist militias, which eventually coalesced into the nascent Israel Defense Forces, sometimes destroyed villages and expelled their inhabitants, and there was a mass flight of Arabs from cities like Haifa and Jaffa. By the end of the war, what emerged was a Jewish state with a comfortable Jewish majority along with a substantial though not overwhelming Arab minority. The refugees, for the most part, were settled in camps in the surrounding Arab nations of Syria, Lebanon, and Jordan, as well as in the West Bank and Gaza, which were occupied by Jordan and Egypt, respectively. Jordan alone granted the refugees citizenship and absorbed them into the general population. Elsewhere, however, refugees remained stateless, left to the tender mercies of the international community.

From the beginning, pressure was brought to bear on Israel to allow the refugees to return, and from the beginning Israel steadfastly refused to do so, believing that it would destroy Israel’s Jewish character and precipitate another, perhaps even more brutal war. Wilf and Schwartz reveal that this was in fact precisely the Arabs’ intention. The Arab media spoke openly of establishing a “fifth column” within Israel by repatriating the refugees, and the authors record Palestinian historian Rashid Khalidi’s view that the Arab mood at the time made it clear that the right of return “was clearly premised” on “the dissolution of Israel.” In addition, the Palestinian leadership was initially unenthusiastic about the return of refugees, which they believed would imply a recognition of Israel’s existence to which they remained implacably opposed. For a society deeply rooted in concepts of honor, dignity, and humiliation, such an acknowledgement of defeat was simply unthinkable.

Contrary to the claims of Israel’s opponents, Wilf and Schwartz persuasively argue that the new state was under no moral or legal obligation to allow the refugees to return. During the late 1940s and early 1950s, the concept of population exchange between belligerent national groups in conflict over territory was considered lamentable but inevitable. Consequently, the laws pertaining to refugees often forbade the opposite: States could not force refugees to return to places when to do so might cause further conflict or instability. Emphasis was therefore on resettlement in host countries, usually with a corresponding ethnic or religious majority. This held true for the mass expulsions of ethnic Germans from Poland after World War II, and the almost contemporaneous exodus of both Muslims and Hindus to Pakistan and India, respectively. Importantly, it also applied to the hundreds of thousands of Jewish refugees expelled from Arab and Muslim countries following the 1948 war, who were resettled in the new State of Israel.

Once the Arab and Palestinian position on return shifted from a fear of recognizing Israel to the idea of building a fifth column within the state to wage an indefinite war against Zionism, Wilf and Schwartz write, “The state of Israel… was being asked by the Arabs to perform an extraordinary act: it was called on to admit to its sovereign territory hundreds of thousands of Arabs, against international norms of the time, without a peace treaty, and while the Palestinians and the Arab world continued to threaten it with another war—even calling the refugees a pioneer force toward this end.”

Although anti-Zionists today insist that Israel’s refusal to accept a return of the refugees was a uniquely heinous violation of human rights and international law, it was entirely consistent with the moral and legal norms of the time.

II. Renouncing resettlement

Interestingly, the violation of these norms and the exceptional demands made on Israel in regard to the refugees were chiefly legitimized not by the Arabs but by the West. Wilf and Schwartz identify international diplomat Folke Bernadotte as the first architect of what the Palestinians call the “right of return.” Sent to the region shortly after the 1948 war, Bernadotte was the first to engage in what is now known as “shuttle diplomacy” between Israel and various Arab capitals. Hoping to secure Western influence in the Middle East and Arab goodwill, he formulated a brutally anti-Israel plan for peace, which rejected the already-established Jewish state in favor of a federal Palestine. He urged Israel to make major territorial concessions and supported the Arabs’ rejection of the new state.

Wilf and Schwartz argue that Bernadotte essentially designed the international community’s plan to deal with the refugee issue and his approach helped to ensure its intractability: “He was the first to decide that responsibility for the stateless Palestinian refugees should fall on the international community via the United Nations: the Arabs were inhabitants of the territory entrusted by the international community to Britain as a mandate, Bernadotte judged, so they understandably expected tangible assistance from the United Nations.”

“Bernadotte also demanded the return of the Arab refugees to the territory of the state of Israel,” they add. “In so doing, he operated against the conventional view at the time, as noted, that the ethnic separation of rival populations was a lawful, moral, and legitimate tool of peace-making. He accepted the Arab position and called the refugees innocent victims.” A refugee return, Bernadotte believed, was an issue of “elemental justice.” Henceforth, Palestinian refugees would be treated differently from refugees in any other conflict.

In the midst of this diplomatic activity, Bernadotte was assassinated by the Lehi, a small right-wing Zionist militia. His plans for reversing Israel’s existence died with him, but the notion that the return of Palestinian refugees constituted a moral imperative did not. In December 1948, the UN General Assembly adopted Resolution 194, which it is often said, concretized this obligation in international law. Wilf and Schwartz correct the record on this point too. The UN General Assembly, they point out, does not have the power to create a “right” and remind us that the Arab states actually opposed the resolution because endorsing it would imply their recognition of Israel. It was only later that the Arabs seized on a single clause relating to the refugees as absolute and inviolable once they grasped its utility, not as a statement of rights but a political weapon. Israeli leaders were not slow to recognize its power. As Israel’s first prime minister David Ben-Gurion observed, “We can be crushed, but we will not commit suicide.”

During the 1950s, US president Harry Truman’s envoy Gordon Clapp attempted to persuade the Arab states to agree to a resettlement plan in exchange for economic aid, but was flatly rejected for two reasons. First, say Wilf and Schwartz, “Arab public opinion saw rehabilitation of the refugees as nothing less than treason” and, second, the refugees themselves vehemently opposed it. This was just one of numerous attempts to find a humane resolution to the humanitarian crisis produced by the 1948 war. One of the saddest stories in the book is that of Palestinian leader Musa Alami, who attempted to rehabilitate refugees in the West Bank, establishing an agricultural community to do so. These efforts met with initial success but were reduced to literal ashes when he was branded a traitor and his settlement burned to the ground.

The fate of Alami’s initiative was an emblematic episode. Following the Six Day War, during which Israel captured the West Bank from Jordan and the Sinai and the Gaza Strip from Egypt, the refugee camps permanently renounced any further attempt to improve refugee conditions and turned instead toward air piracy and other acts of murderous terrorism. Led by the Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO), an array of terrorist groups turned the camps—ostensibly under unbiased international supervision—into both a power base and an almost inexhaustible supply of recruits. Indeed, most of the Black September terrorists who committed the Munich Olympics massacre in 1972 were the children of refugees.

The culture within the refugee camps, Wilf and Schwartz argue, renewed Arabs’ rejectionist and genocidal ambitions, and the Palestinians there renewed their commitment to an indefinite war of elimination. Their hatred was now fortified by a self-righteous belief that destroying the Jewish state was not merely desirable, but an expression of absolute justice for the dispossessed. “The Palestinians of the refugee camps developed a collective consciousness in which they saw themselves as a persecuted ethnic group having suffered the greatest calamity in the history of mankind,” they write. “Edward Said described this mood well later, writing, ‘The Palestinians have endured decades of dispossession and raw agonies rarely visited on other peoples.’”

In effect, despite terrorism and genocidal aspirations that clearly ran contrary to anything resembling international law, the international community effectively agreed to sponsor a situation in which “the Palestinian refugee camps became a state within a state, a closed territory in which poisonous, hate-filled rhetoric sprouted and from which it spread.”

III. UNRWA’s baleful influence

Over time, the international community’s sympathy for the Palestinian cause and the plight of its refugees led it to become an inadvertent supporter of, and occasionally an active collaborator in, Palestinian terrorism. The clearest expression of this paradox, say Wilf and Schwartz, is the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA). This body, they claim, which operates the camps and advocates on behalf of the refugees in international fora, both perpetuates and exacerbates the refugee problem and, by definition, the Israeli-Palestinian conflict itself.

The roots of this slow but inexorable corruption were put down in 1965, when UNRWA uniquely extended refugee status to include the descendants of the original refugees. This move effectively caused the number of Palestinian refugees to balloon from a few hundred thousand to many millions at a stroke. “What arose here, therefore, was a unique type of refugee: one who existed primarily on paper,” every one of whom was now demanding to be “repatriated” to a country in which most of them had never lived. Indeed, in perhaps the most damning section of their book, Wilf and Schwartz elucidate in minute detail how UNRWA became, in effect, a Palestinian nationalist organization with disturbing connections to terrorism.

The person most responsible for this absolute identification, they write, was John Davis, the former commissioner-general of UNRWA. By 1970, Davis was openly justifying Palestinian terrorism, fulminating anti-Semitic conspiracy theories, and espousing the inflammatory cliché that “a Jewish state has to be a racist state.” He demanded the return of all Palestinian refugees and their descendants and Israel’s replacement with an Arab state. Davis’s successors would all follow his dismal example. Inevitably, UNRWA became something very like a terrorist organization. Representatives attended the first Palestinian National Council section, its staff were drafted into the Palestine Liberation Army, and its refugee camps became centers of terrorist activity. As late as 2014, schools operated by the agency were found to have contained weapons used by Hamas in clear breach of international law.

Wilf and Schwartz also highlight the egregious abuse of UNRWA’s mandate to provide education for the refugees. As many have pointed out in the past, even UNRWA textbooks used by the youngest children are replete with incitement and anti-Semitism, and reject the possibility of coexistence with Israel in any form. “UNRWA’s education system,” the authors write, “effectively became an instrument for the mobilization of the population of the camps for the Palestinian armed struggle. Nowhere was there any space for the rights of the Jews or the possibility of coexistence in a shared land—an obvious prerequisite to peace.”

In one particularly ominous passage, they remind us that one of Fatah’s leaders, Khaled al-Hassan, acknowledged that “while Fatah’s terror cells could only train one agent at a time, UNRWA schools could train the hearts of the masses.”

IV. Peace processing

The Israeli-Palestinian peace process was inaugurated with the Oslo Accords in 1993. Throughout endless negotiations, the Palestinians’ representatives, the PLO, have never renounced return, and have used the issue to torpedo several sets of talks that might otherwise have achieved some measure of success. Wilf and Schwartz argue that this betrays the essential perfidy underlying the Palestinians’ ostensible willingness to acknowledge Israel’s existence and agree to a two-state solution. The refugee issue is not merely an obstacle, or even the primary obstacle, to peace, it gives away their true agenda.

Wilf and Schwartz argue that, notwithstanding rhetorical commitments to a two-state settlement, the PLO is in fact following a “phased plan” originally adopted in the 1970s, according to which the Palestinian national movement would gain control of any part of “Palestine” it could and then use that territory as a “jumping off point” for their ultimate objective of reconquering the entire land, something Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat attempted unsuccessfully in the Second Intifada. In a particularly chilling locution that was surely deliberate, Arafat’s deputy Abu Iyad admitted that “An independent state on the West Bank and Gaza is the beginning of the final solution.”

The proof of this agenda, the authors say, is the insistence on the “right of return” itself. “In demanding sovereignty over the West Bank and Gaza Strip without dropping their aspirations to return to Haifa, Acre, and Jaffa as well, [the Palestinian leadership] were saying that any change in their position was cosmetic, a tactical move to score points for Arafat and the PLO from the West, without a strategic decision to accept Jewish sovereignty.” To give up the right of return to Israel proper would, in effect, neutralize the demographic weapon and foreclose the possibility of a Reconquista of what was once Mandatory Palestine.

Oslo collapsed when Arafat turned down Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Barak’s offer of peace at Camp David in 2000. The breaking point came on the issue of refugees: “Barak recalled that when Arafat understood that he would have to relinquish the right of return in the form he had been promoting for years, he flatly refused.” The same happened during talks in 2008, and internal Palestinian Authority documents, the authors reveal, show that there is little hope for a change in the Palestinians’ intransigence on this issue: “The Palestinians were presenting themselves as the kind doctors offering euthanasia for a patient who wishes to live.”

The documents confirm that even while negotiating for an ostensible two-state solution, the Palestinians remained committed to returning millions of refugees to Israel, an outcome they vaguely euphemized as a “just” and “agreed” solution. Foreign diplomats readily took Palestinian obfuscation to be reassurances, when they should have been met with the greatest skepticism. The authors argue that the Palestinians are playing the long game. Six million Jews, they believe, simply cannot fight 400 million Arabs forever: “From the Palestinian perspective, full return might take another generation, even two or more, but there is no need to compromise in the interim. With sufficient patience, Palestinians, as a collective, expect to outlive the ‘temporary Zionist experiment’ and reclaim the land, which to them is exclusively theirs.”

To address this problem, Wilf and Schwartz advocate a long overdue paradigm shift, in which the international community tells the Palestinians publicly and firmly that a mass “return” of the refugees to Israel will never happen and that the Jewish state is here to stay. “The resolution of the conflict therefore lies not simply in finding technical solutions to matters of borders, settlements, security, and even Jerusalem—but primarily in getting the Arab world, and specifically the Palestinians, to accept the rightful exercise of sovereignty by Jews in their midst, recognizing that there will be no Palestinian return to the state of Israel.” The Palestinian demand for return, they say, must be delegitimized and replaced with “full legitimacy, support, and fuel for a moderate Palestinian vision that does not entail the erasing of Israel under any guise.”

The next step is for the UN Security Council to adopt a resolution rejecting refugee return and for the international body to then dismantle UNRWA, which today serves a shocking five million people, the overwhelming majority of whom are not even refugees by any reasonable or normative definition of the term. The task of resettling or providing citizenship to refugees in Syria and Lebanon would then be dealt with on a case-by-case basis in the normal manner by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, the agency established to deal with all other refugees in the world. In the West Bank, the Palestinian Authority must absorb its refugees. Gaza is currently ruled by the theocratic terrorist organization Hamas which makes the problem there more complicated, but alternatives to UNRWA could be found in other international agencies untainted by corruption and terrorism.

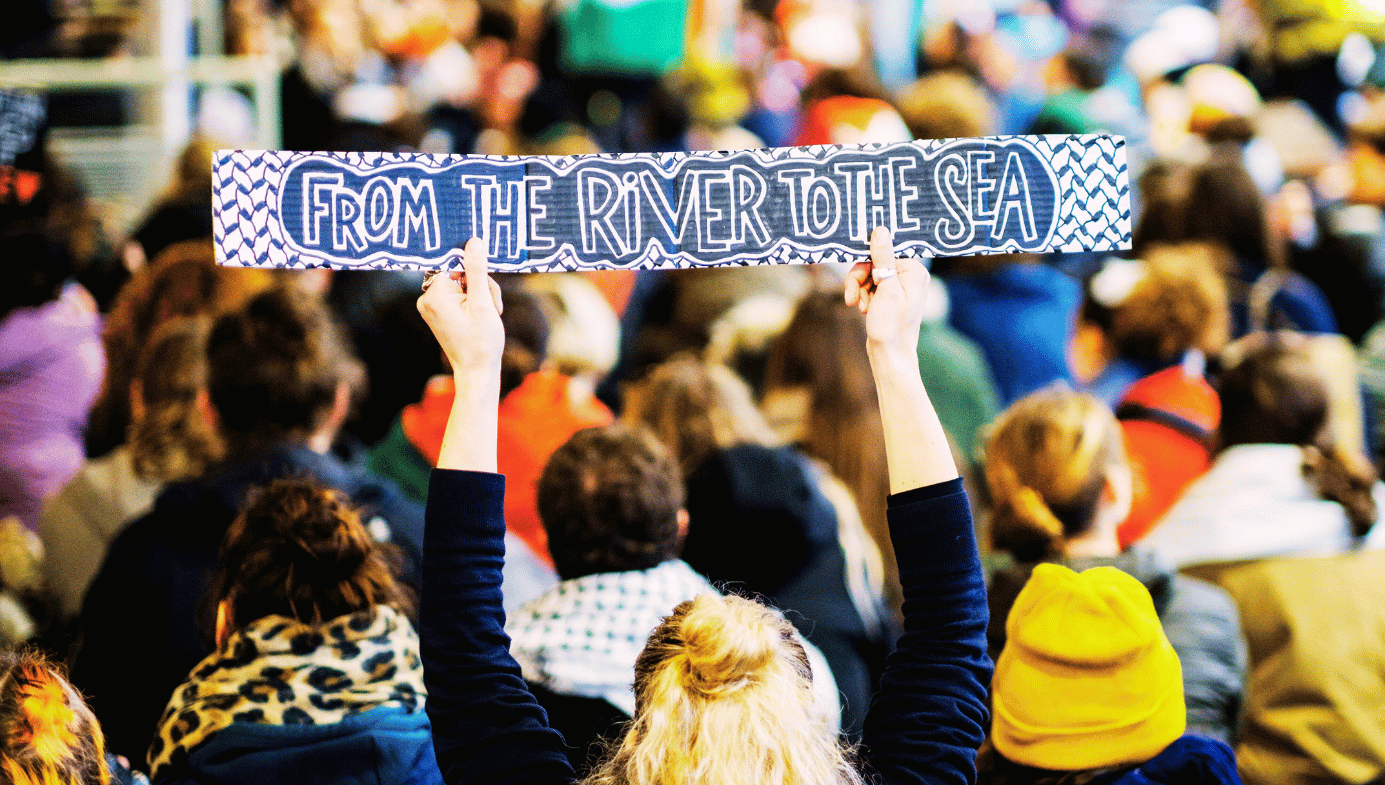

If peace is to be achieved, Wilf and Schwartz argue, it is critical that the international community take concrete action to show that it will not support anything resembling the elimination of Israel as a Jewish state. “The road to peace can only be cleared if the Palestinians understand that their claims over the whole of Palestine from the river to the sea have no international support, just as Israel has no international support for its claims to territory beyond the 1967 line,” they write. “Palestinians would probably continue dreaming of having Jaffa and Haifa, just as Jews would continue dreaming of having Hebron and Judea—but both these dreams would remain precisely that. They would be dreams, not claims, and certainly not claims enjoying even tacit international support.”

V. The path to painful compromises

The War of Return is an important book and, unquestionably, a welcome corrective to the plethora of myths, lies, and misconceptions that litter the discourse on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. To the extent that it is a brief for the Israeli side of the conflict, it succeeds brilliantly, cutting through decades of vitriolic attacks on the Jewish state without engaging in partisan demagogy or its own brand of misrepresentation. In particular, it confronts partisans of the Palestinian national movement with the essential deception at the heart of their ideology: While declaring themselves adherents of justice and human rights, they support and enable a movement committed to terrorism as a means and ethnic cleansing as an end.

Nevertheless, something is missing from an analysis which concentrates on the legal and practical implications of the concept of return and its detrimental effects on the peace process. The authors are correct to say that peace can only come through the renunciation of return, but they do not acknowledge a painful irony for the Jewish people in their brief concluding reference to dreams. This irony is that Zionism itself is, in its essence, a modern political expression of a 2,000-year-old dream of return and redemption. And even with our return to our homeland and the establishment of a state in 1948, many of us still dream of a rebuilt Jerusalem, a Jewish Hebron, the Complete Land of Israel unified under a Jewish republic, and even a Third Temple. The Zionist movement has always shown itself willing to compromise on those dreams and exchange maximalism for peace. Nevertheless, those dreams do exist, and Jews understand their terrible weight and how painful it can be to give them up.

Whether Palestinian refugees will dream of Jaffa and Haifa for another 2,000 years is unlikely given that they are mostly adherents of religions whose sacred lands are elsewhere. Even so, in their very dreaming they have a kinship to the Jewish people, and we should acknowledge that among dreamers of this kind there must be some measure of sympathy and common understanding. Perhaps Israelis and Palestinians can be reconciled not just through the Palestinian renunciation of the dream of return, but in a mutual partial renunciation of each other’s dreams, and the acknowledgement that, in this, we are very much alike.

The truth, however, is that for all its hardened realism, Wilf and Schwartz’s book seems at times overly optimistic. The international community is unlikely to force the Palestinians’ hand on anything, and given the power of the Arab-Muslim bloc at the UN, the possibility that UNRWA will be dismantled is remote. But the largest obstacle to such a change relates not to the international community but to the manner in which the refugee issue and indeed Israel’s existence itself cut to the quick of Arab-Muslim identity. The obstacle may be, ultimately, psychological rather than political, and by no means confined to the Palestinians.

The reason for this is inadvertently indicated by the authors when they note of Musa Alami’s rejection of Israel’s right to exist, “Full Arab independence, Alami wrote, could be achieved only if every trace of foreign imperialist presence was erased.” This has become the Arabs’ most essential argument: Israel is a foreign, imperialist, colonialist imposition, and so justice demands that it be eradicated. This belief justifies even the most horrific acts of terrorism, and is necessitated by a historical irony: that the entire Arab presence in the land of Israel is itself the result of imperialism and colonialism. The Arab people are, in fact, foreign to the Levant and indeed to much of the Middle East and North Africa. Israel is a mirror in which they see their own imperial presence, which is illegitimate by their own post-colonial standards.

Hatred of Israel is used to absolve Arabs’ own historical sins: Imperialism, colonialism, ethnic cleansing, the appropriation of land and other people’s holy sites, the bloody conquest of entire continents. Without these historical developments, the Arab-Muslim world as presently constituted would simply not exist. Projecting these sins on to a hated Other is an evasion of accountability—a way to bury their own historical guilt beneath the violent self-assertion of an unchallengeable myth of indigeneity and noble victimhood. In its insistence on return, the Arab-Muslim world holds out the hope that “justice” can be done—the Other can be eliminated, and their own original sin remain suppressed and denied indefinitely.

But there is nothing uniquely monstrous about the history of Arab-Muslim imperialism. For all of human history, great empires and religions—and Islam has been both—have built themselves in precisely the same way. As Balzac put it, behind every great fortune lies a crime. And today’s Arab Muslims are no more guilty of these crimes than Germans born after World War II are guilty of the Holocaust, or today’s Americans guilty of the institution of slavery. The problem is that the Arab-Muslim world has dealt with its history in a particularly dysfunctional manner. It rejects the self-criticism it demands of the West, and indeed of Israel, in favor of self-pity and hatred. Historical sins demand an internal moral struggle, not the unending persecution of a convenient scapegoat. If the international community should work toward anything, it is toward encouraging the possibility of such a reckoning.

And this, perhaps, is where the real solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict lies. Wilf and Schwartz provide an excellent historical study of, and useful practical suggestions for dealing with, one of the most intractable aspects of the long struggle between the two peoples. But I doubt that these suggestions will prove effective unless and until the Palestinians, along with the larger Arab-Muslim world, come to terms with the fact that they are not uniquely persecuted, that Israel is not uniquely evil, and that compromise is therefore possible after all. Only then will Palestinians be in a position to renounce the irredentist dream of return that stands so stubbornly in the way of the dream of peace. Unfortunately, such a reckoning is not likely to come soon. In the meantime, Wilf and Schwartz’s fascinating critique of one of the myths that prevents it is at least a step in the right direction.