Top Stories

Nineteen of the Loneliest Films Ever Made

Some of them are stylish pop art or lowbrow trash—depending on how initiated you are with their appeal. But they will also make you cry or simply stare at the screen with a detached jaw as you begin to rethink their implications behind your sterilized walls.

By withdrawing ourselves into our bedrooms, we’ve become introspective and foggier. The weathering effect of a global pandemic has raised a pall over our dusty aesthetics. Deprived of sunlight and friends—even the aroma of a cup of Starbucks coffee becoming foreign—we’re all a bit more gothic and darkly imaginative, like Winona Ryder in Beetlejuice (1988). By engaging in a very necessary act of separatism, we’ve found ourselves bizarrely connected by a daisy-chain of emotions that seems wounded by an uncertain and cybernetic future. Our rate of media consumption has increased. What if we get sick and miss out on experiencing French new wave? What if a dear friend dies before we can drink coffee and talk about David Lynch’s G-rated Disney movie? So, we’ve been creating lists with the frequency of a sleep-deprived and sallow Kurt Cobain. By the summer, we’ll have ranked ourselves into a dizzying state of curated paralysis.

We collectively realize this might be our last chance to read Infinite Jest or delve deeply into Korean cinema or German Expressionism. Fueled by anxiety and our endless curiosity for the unseen, we are now, more than ever, connoisseurs on all matters of taste. But too often when we’re crippled with the strangling vines of fear, we seek to escape through the cushioned standards: Frank Capra’s clean-cut romanticism, the overconfident jingoism of the Reagan era, the satisfying but hollow blockbusters of the ‘90s, an overly relatable Pixar movie, and the formulaic Spielbergian pop that always leaves you feeling grossly sentimental. But there’s something far more pleasurable about using the cinema as a reflection of your psyche—rather than as a numbing agent. The following collection of films will inspire existential questions that many of us are currently incapable of answering, but in time, by bathing in their forgotten beauty and wrestling with their messages, you will begin to reflect upon your own mortality. You will begin to question your vanity and cracked reflection, obsession with youth, death, nostalgia, and unwillingness to face the cold hard facts. We are temporally friendless. We are alone. The TV is our only friend.

These are more literary, often black-and-white classics and forgotten masterpieces all filmed prior to the millennium, which require reevaluation in our post-millennium dystopia. Some of them are adaptations of novels, or the product of screenplays written with the panache and imaginative gaze of a novelist. They create more questions than answers. Some of them are stylish pop art or lowbrow trash—depending on how initiated you are with their appeal. But they will also make you cry or simply stare at the screen with a detached jaw as you begin to rethink their implications behind your sterilized walls. They are the sort of films that can be accompanied with hot coffee, pie, and a vintage paperback. Add them to your astronomically out-of-control collection of lists, or simply watch them before you catch the flu or have to go back to work.

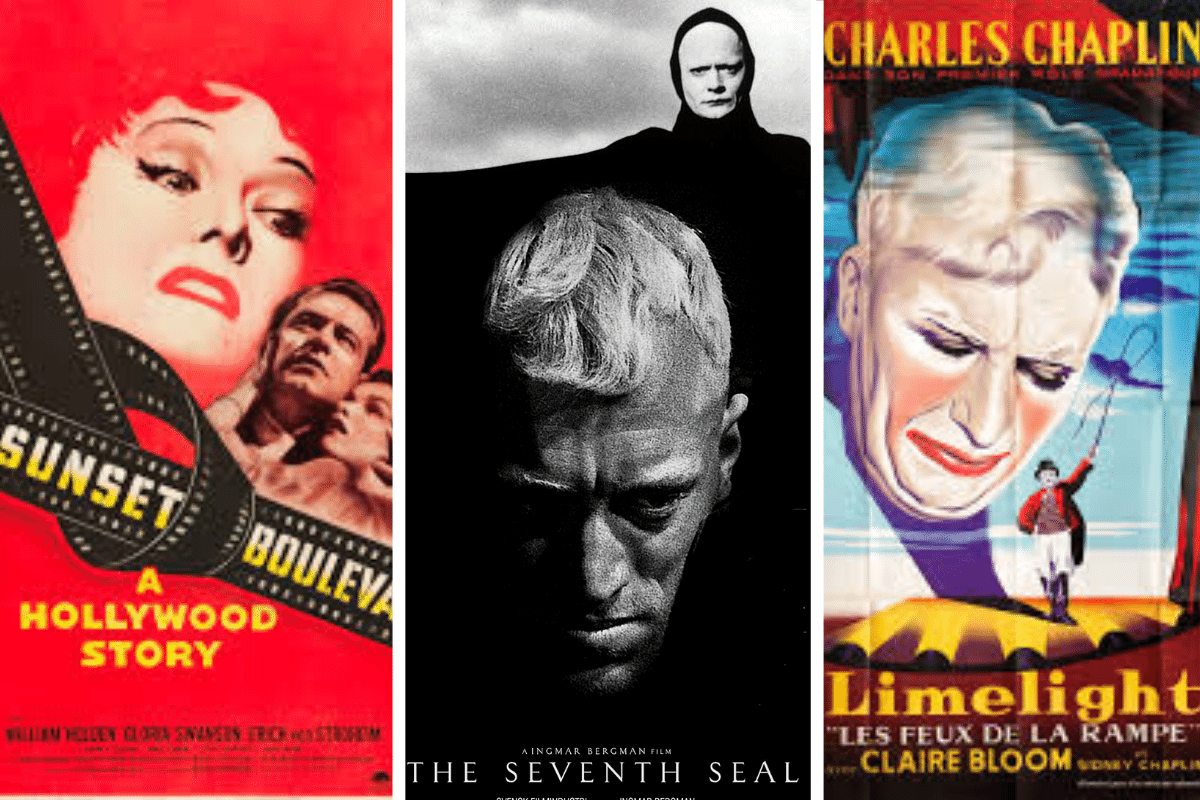

Billy Wilder’s spooky exposé is what happens when you view a decaying headshot under a magnifier. It’s at once celluloid self-immolation—the cynical writer penning his own lurid gossip diary, covered in ash and sweat—and absurdist treatment of Hollywood’s infatuation with young flesh. The result is gothic horror trapped inside the mansion of a fading star who hasn’t been in orbit since Lindbergh flew over the Atlantic.

Picture a tragic clown (Charlie Chaplin) stumbling towards his curtain call with a bottle in one hand and his pride in the other. By the end, you end up weeping for both the clown and the actor who portrays him, as he begs for applause, while constantly giving his audience a reason to walk out on him. Limelight is the funeral procession of a lovesick clown.

It was black and white, when the studio wanted it to be color. It was shot in severe, urban locations, when most films of the era were shot inside air-conditioned studios that looked like illustrations in technicolor. Kazan’s minimalism is the background of a cold ethics course on the suffering that transforms Brando from a gangster’s stooge into a martyr for the working-class.

A crusading knight challenges Death to a game of chess. Beyond the medieval longline, Ingmar Bergman uses the knight’s chessboard to move us through a plague-infested landscape that’s idyllic, like a Millet painting, and morbid, with charcoal grays and glimmering whites that make it look like German expressionism.

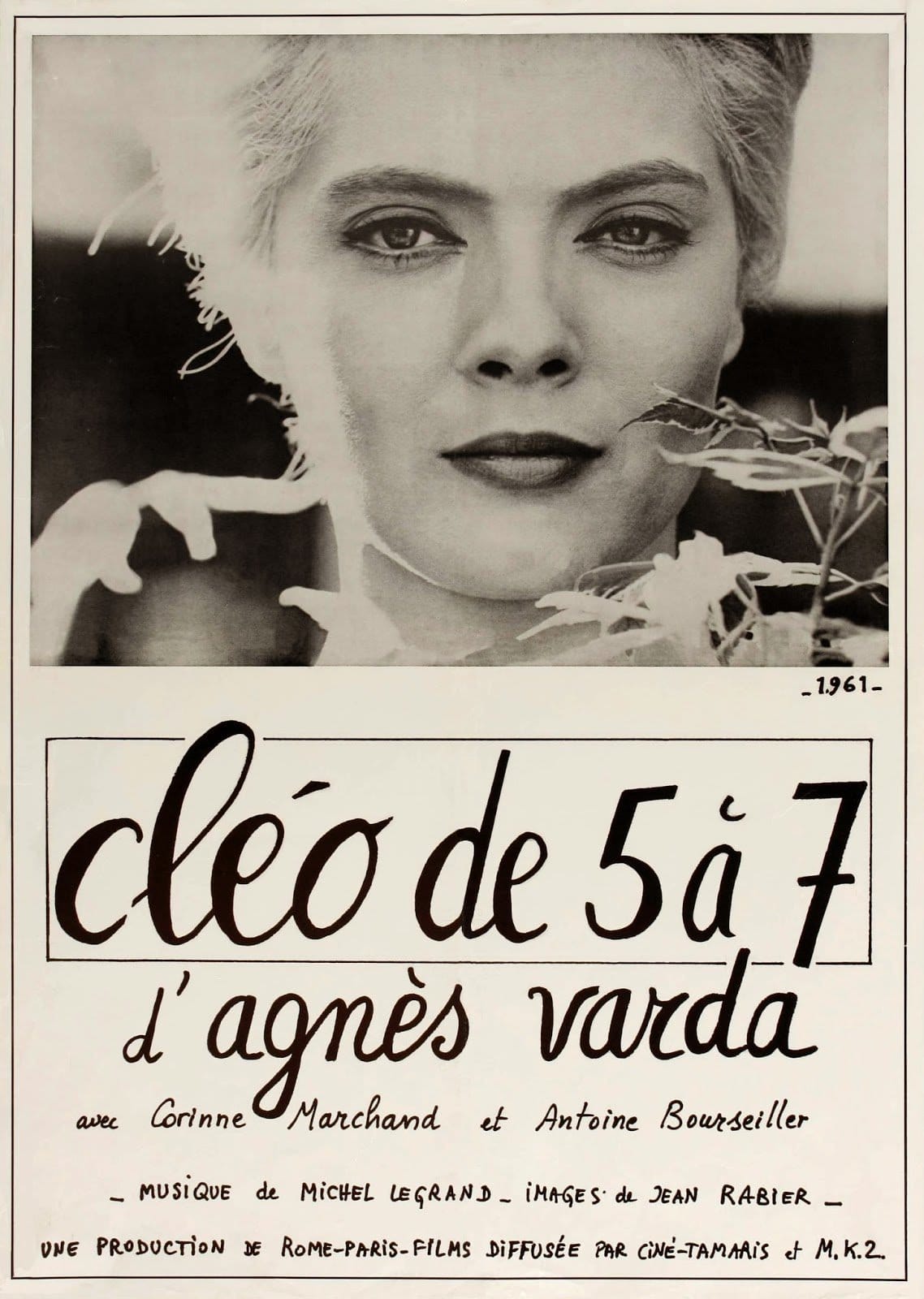

Agnès Varda creates a stylish jaunt through cosmopolitan Paris, which seduces you with glamour and reflective surfaces, while its subject—a vapid, childlike French pop star—spends her day distracting herself from the quiet agony of believing she is terminally ill. She is a reflection of the melancholic child. Cléo is like a wildflower searching for sunlight between the billowing gray clouds of Paris. There are scenes when you simply feel like a voyeur trying to find some meaning out of her fleeting youth.

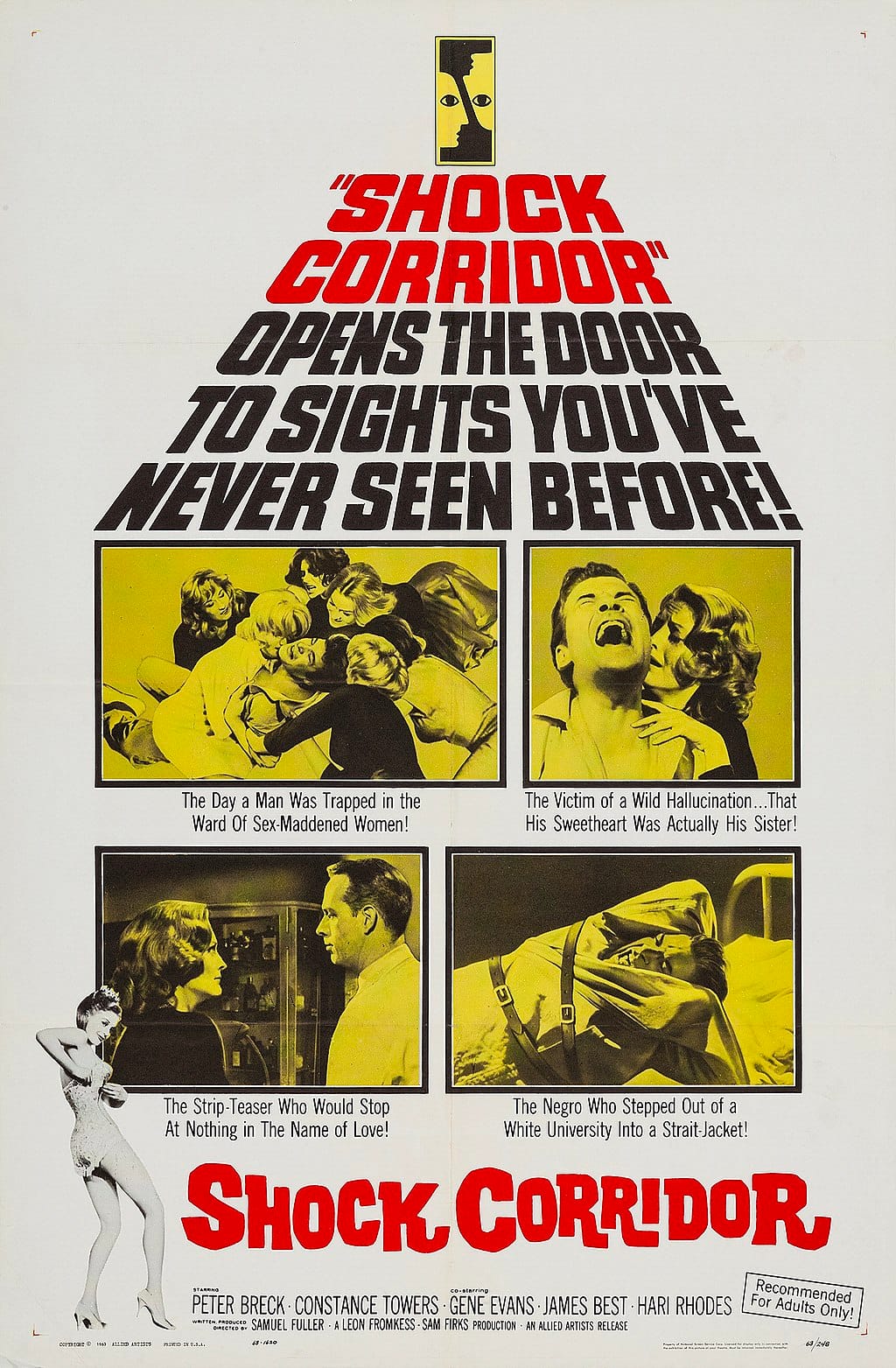

Sam Fuller’s psychodrama begins as a shocking indictment of journalistic malpractice. It concerns a preposterously ambitious reporter who has decided to commit himself to a psychiatric ward in order to win the Pulitzer. As he begins to crumble, the message evolves into a Nietzschean reminder that staring into the abyss can turn you into a reflection of its blank terror. Fuller uses the psych ward as a mirror of the abyss. The straitjacketed journalist becomes our eyes, as he witnesses race riots, white supremacy, the bigotry of the South, the KKK, and a period in American history when mental health patients were treated like convicts. The film begins and ends with a quote from Euripides: “Whom God wishes to destroy he first makes mad.”

This is the first and most earnest adaptation of Richard Matheson’s I am Legend, which stylistically amounts to a film-length Twilight Zone episode starring Vincent Price. It was filmed in Rome, amongst its ancient cemeteries, churches, and fascist architecture, which enhances the alienation of Price’s American scientist—who plays a bebop record as zombied vampires descend upon his doorstep. Price’s air of sophistication produces the feeling of watching what’s left of the intelligentsia being devoured by the deadened horde.

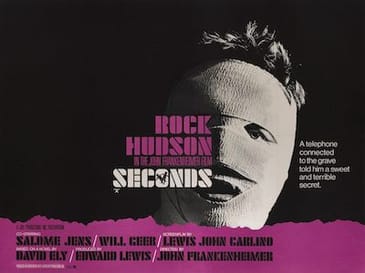

It is one of the most unconventional looking films of its time: perspiring close-ups, psychedelic camera angles, cinéma vérité orgies, graphic footage of facial surgery, and a thick atmosphere of paranoia that begins with Saul Bass’s phantasmagoria credits and becomes positively nauseating by the final act. Frankenheimer manages to capture Rock Hudson’s most intense performance, who is the expensive new face of a pudgy middle-aged banker who’s hired an agency to reinvent him. He soon finds himself trapped in a kind of permanent acid trip where he’s caught between his new body and his old brain. It almost feels like an allegory for Rock Hudson’s life as a closeted gay man who was playing someone else for his entire life.

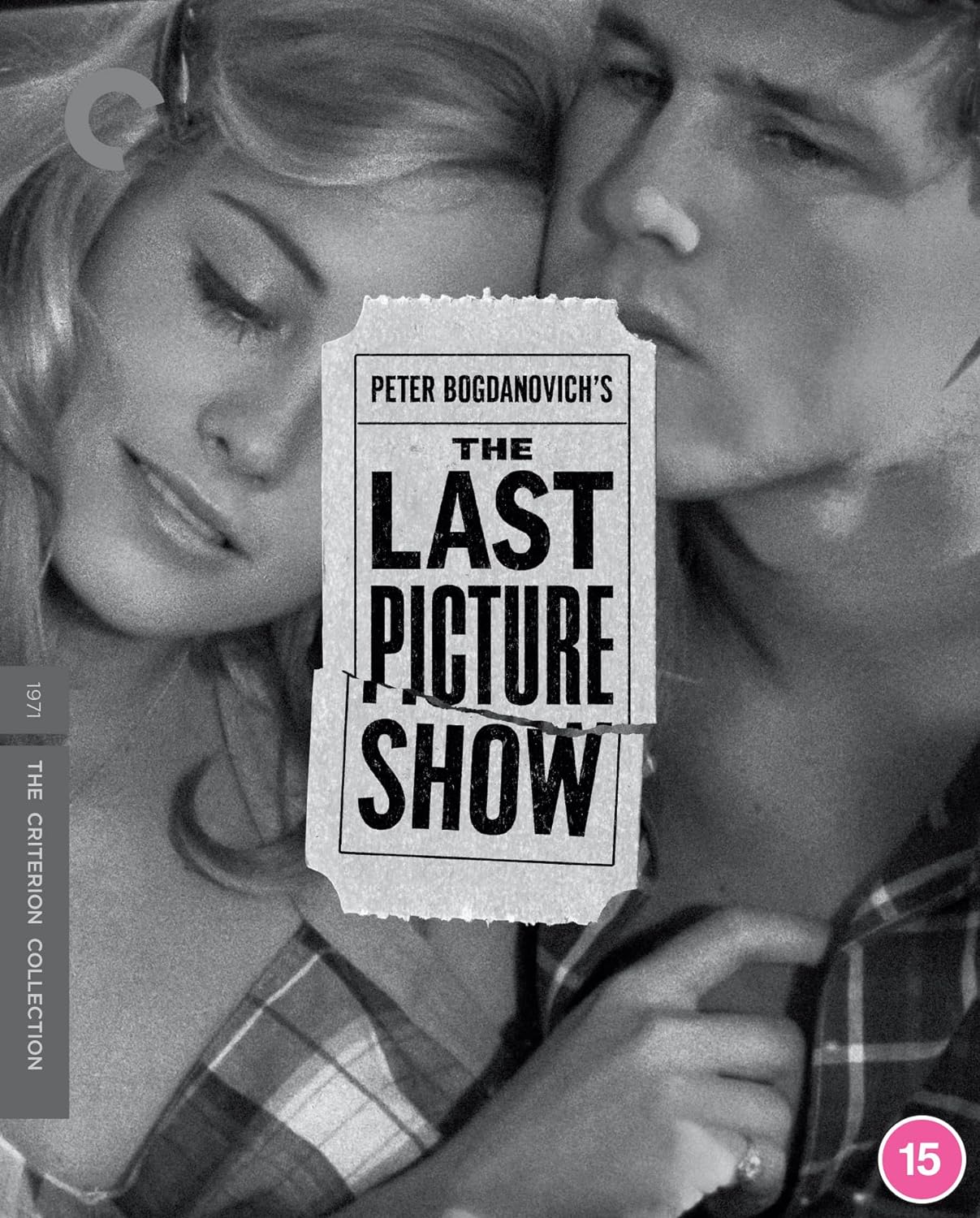

It’s a sexually frustrated tragedy that takes place in a version of Texas that looks like a Hank Williams song. The effect is a realistic and sunless portrayal of rural teen drama that has almost nothing in common with the malt shop romanticism of American Graffiti (1973). Set in 1951, and shot in black and white, the film explores the internalized frustration of horny teens in a stark and nihilistic small town, which would have practically been banned had it been released two decades earlier. Bogdanovich manages to use sexual desire to draw the eye towards a fading photograph of small-town America.

It was survival camp for chauvinistic drunks; a frigid horror covered in crunchy and moist special effects that were uncomfortably delicious, especially in the dog kennel scene, where a parasitic shapeshifter invades the body of a dog and transforms it into a gooey worm-like thing. Initially, for reasons that are unfashionably snobbish, John Carpenter was torched by his critics. Roger Ebert said it was, “the most nauseating thing I’ve ever seen on a movie screen.” Carpenter was described as a “pornographer of violence.” His career was in ashes. In the ‘90s, on VHS and cable, The Thingbegan to attract the geek obsession of a classic PC adventure game. For sci-fi horror fans of a particular age, The Thing is comfort viewing. For everyone else, it’s a “guy movie” that’s aged about as well as its VHS cover.

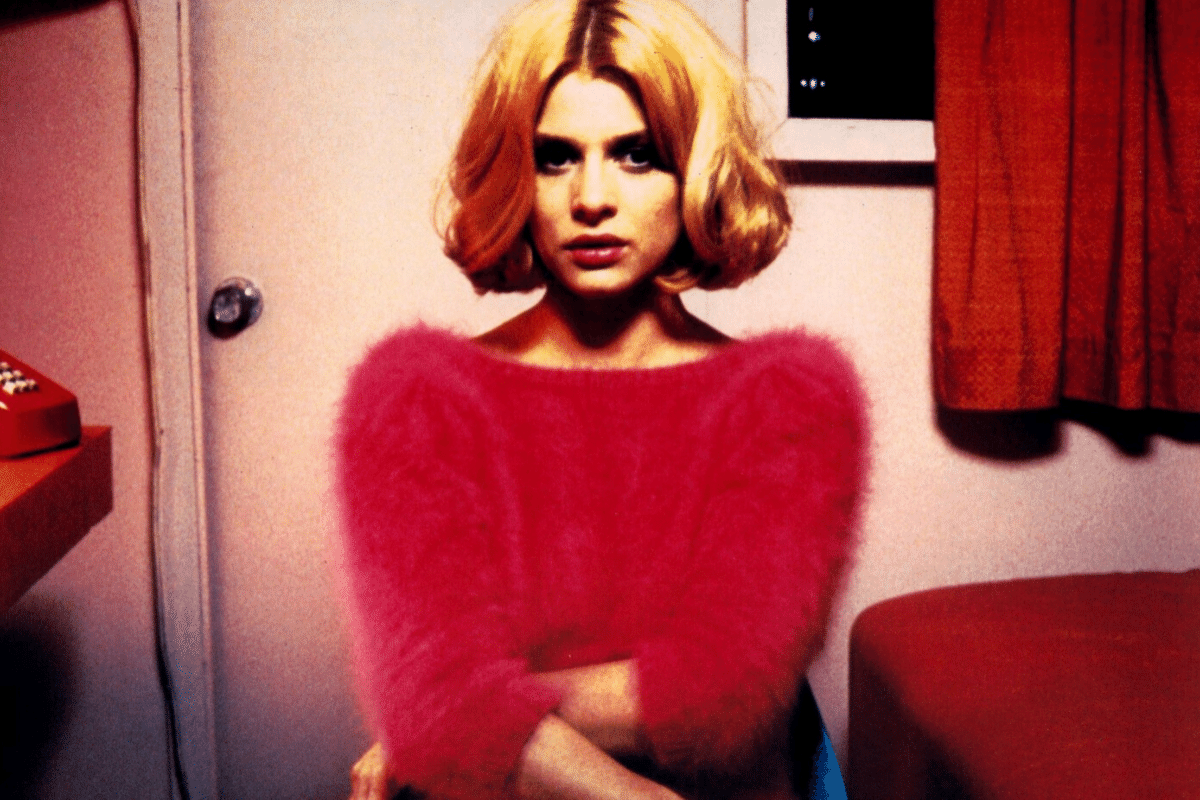

Imagine what you get when a German filmmaker tries to visualize a Sam Shepard script: isolated moments of tenderness, neon lamps, molten-orange sunsets, and Ry Cooder’s twangy guitar the landscape Harry Dean Stanton roams as a raggedy drifter searching for his soul. When he finally tracks down his transient wife, played by Nastassja Kinski in a hot pink mohair sweater, the film transforms into an evanescent romance. Amongst schmaltzy Reagan-era road movies, Paris, Texas is minimalist poetry.

Nastassja Kinski in Paris, Texas (1984)

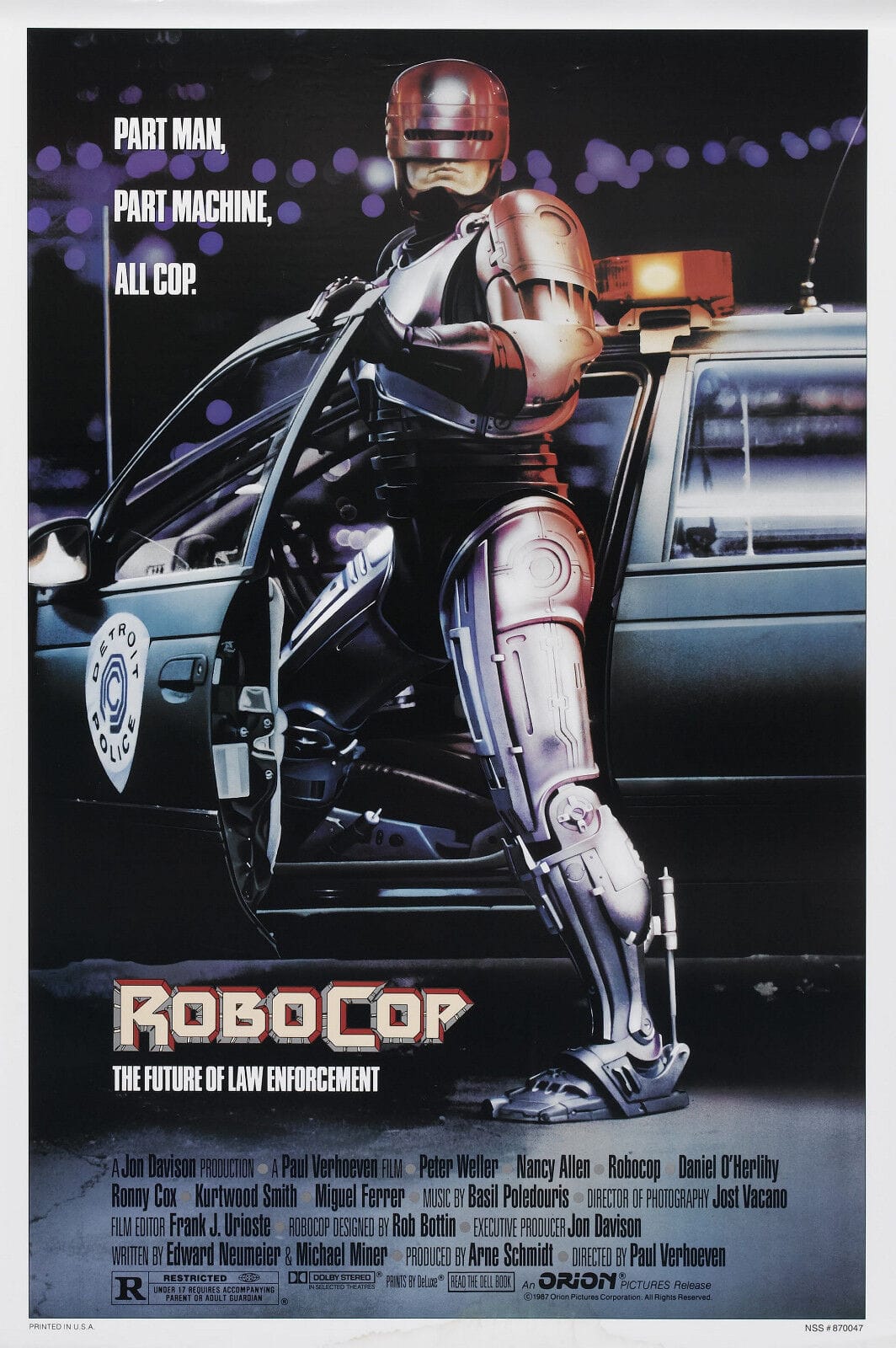

Paul Verhoeven’s absurd attempt at a superhero film does one thing better than any other film in history: lambasting corporatism with the sadistic humor of a machine-gun toting clown. While it’s impossible to say something new about such a flawlessly cut piece of science fiction, it seems the Trump era is providing further justification for RoboCop’s mockery of America. Underneath its action movie packaging and killer one-liners, RoboCop is a comedy for the urban working-class. Film critics have studied it as allegory for Christ’s resurrection, or an example of liberal fascism in the cinema. Kids have accepted it as a steely superhero saga. The action figures are pieces of art. RoboCop is also a terrifying reminder that everyone is expendable in corporate America. It is thus the most important superhero film ever made.

It’s a twinkling fairytale that works as both a suburban satire and teenage Frankenstein film. In terms of its pastel-colored, goth aesthetic, Edward Scissorhands looks like a child’s illustration of a depressed California suburb. Flipping through its glossy pages, Tim Burton goes underneath the manicured, lush front lawns of suburbia to reveal a damp layer of prejudice that views any kind of change like an alien invasion. It is the blend of a Twilight Zone episode with an artistic teen movie.

Clerks is the cinematic equivalent of a job that’s gone out of fashion. Immersing yourself in it has the effect of flipping through faded polaroids of extinct punk bands. If you’ve ever found yourself as a dejected clerk in a downtrodden family-owned business, then this film is a documentary. There’s a lot of geek scholarship on this film’s generation-defining aesthetic and oversized flannel disillusionment, but for the moment, with so many of us jobless and deprived of classic American customer service, it seems Clerks momentarily functions as a fantasy that reaches beyond the empty Prozac bottles of Generation X.

Scored almost entirely by an accordion and Neil Young’s untamed electric guitar, Dead Man is not only the most enigmatically scored western—it’s also the most symbolic: the elegy of a dying accountant who is shooting his way out of purgatory with a six-gun. Jim Jarmusch uses his unconventional version of the Old West to sketch a macabre fantasy, which he handled with a morbid cheekiness that was rhythmically hooked to Young’s guitar and Depp’s psychedelic performance. Dead Man is one of the most mystifying and introspective westerns ever made, and the only one that treats the Native American as being superior to the “stupid fucking white man.”

Disconnecting from the Internet is practically impossible. To do so would require leaving your life behind. This fact means we’re all just walking the fine line between Truman Burbank and a blissfully ignorant YouTube celebrity. We’re digitally enhanced, semi-free actors who’ve been cast in a play that rewards 24-hour face time and hallow giddiness. Everyone seems happier than they really are. From the moment we leave the womb, the children of the 21st-century struggle with the existential crisis in The Truman Show, which raises a Descartesean question similar to the one in The Matrix (1999). In Peter Weir’s slickly shot criticism of TV culture, Truman Burbank (played by Jim Carrey) becomes self-aware enough to realize he’s trapped in a simulation. He is given the option to choose his path: a 24-hour livestream inside an artificial suburb, or the slightly terrifying prospect of cutting his fiber optic umbilical cord and becoming untethered from his friendship, job, wife, and the sun itself. We’re all Truman Burbank.

Gary Ross’s cult classic is impossible to appreciate without first understanding how obsessed Generation X was with ‘50s kitsch, or its illusory promise. Ross saw this every night on Nick at Night, or during daytime reruns of “I Love Lucy;” its schmaltzy theme song was as recognizable in the ‘90s as the first two chords of ‘Smells Like Teen Spirit.’ Color TV sets in the ‘90s were becoming mood-enhancement vehicles for manically depressed teenagers. White picket fences and square-jawed dads were a campaign pitch in the Reagan era; for Generation X, the phony but confident paternalism was a way to escape their flannel-shirted aimlessness. In Ross’s film, a sentimental teenager and his sexpot sister are zapped into their TV sets and trapped inside a sitcom. Ross’s film proceeds to deconstruct the black-and-white myth by filling it with sexuality and a diverse palette of colors. Pleasantville presents a metaphor for Elvis Presley’s debut on Ed Sullivan.

It’s an endlessly quotable schizo-drama that’s become the most fashionable film to like from the ‘90s; Fight Club is also a clobbering, jaw-cracking depiction of anti-corporate nihilism that has become A Clockwork Orange(1971) for older millennials. It is a film that is at once impossible to take seriously, but also so bizarrely influential that it feels like a social movement—like grunge or the Sex Pistols. Its final scene has replayed in the minds of every twenty-something that’s been ghosted by corporate America.

It’s David Lynch’s only Disney movie, which is delicately illustrated with scenery that looks like it’s been pulled out of the pages of National Geographic. The story concerns an aging man who travels across the heartland on a dilapidated lawn mower, hoping to reunite with his brother (played by Harry Dean Stanton). It’s not only Lynch’s most romantic film, it’s also the only one where his strange interpretation of Americana becomes almost Rockwellian. There is nothing Lynchian about Alvin Straight, who’s a swisher-smoking wiseman who shares his thoughts over crackling campfires and warm meals—each time his eyes filling up with tears. Though it’s based on an unusual story that made headlines in 1994, Lynch’s interpretation of Straight’s story is elegiac. This is a film about an aging outlaw taking his last ride towards the sunset.