A review of The Decadent Society: How We Became the Victims of Our Own Success, by Ross Douthat. Simon & Schuster (February 25 2020) 272 pages.

Writing about decadence can be symptomatic of the condition. How many conservatives—this reviewer included—have eased out article-length moans about sclerotic institutions, falling birth rates and mindless popular culture without as much as a thought of having an effect on them. In our lazier moments we are not opposing decadence but merely providing a soundtrack.

I suspect that Ross Douthat knew this when he wrote The Decadent Society. Douthat has long been an outpost of conservatism at the New York Times. The Grey Lady specialises in bland liberal conservatives like David Brooks, Bill Kristol and Bret Stephens but Douthat is both more traditional and more incisive. A social conservative, he also has too much mischief and curiosity about him to succumb to the stuffiness of the stereotype.

Readers who might fear that a book bearing the name The Decadent Society would be humourless and cranky, then, need have no such fears. The prose is brisk and teems with interesting facts and observations. Douthat is more pithy than ponderous. European liberals assumed “that if some liberty is good, then more liberty must always be better.” Japan’s “combination of virtual extremes and a peaceful, sexless descent into societal old age may be a template rather than an outlier.”

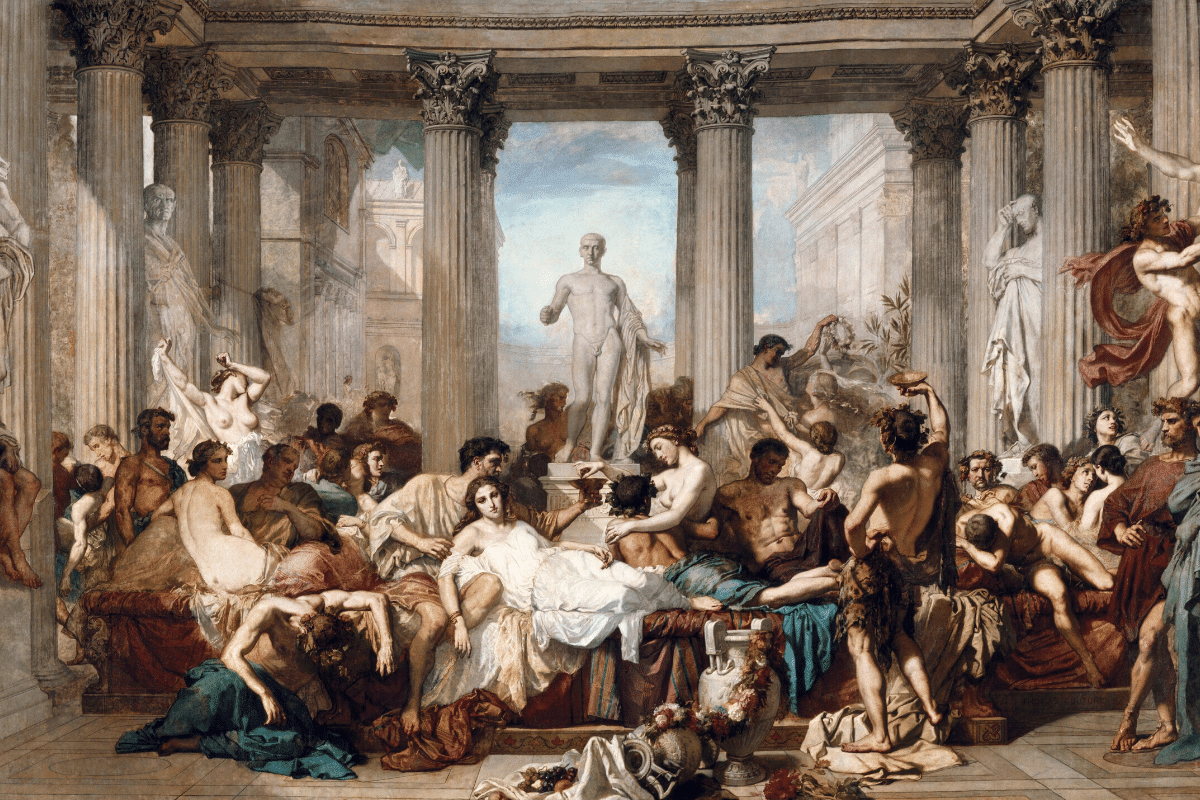

What is decadence? The term inspires thoughts of the lazier explanations for the fall of the Roman Empire, where a decline in civic virtues and martial spirit is said to have made the Romans vulnerable to barbarian invasions. This account has thickened history with moralism—summoning to mind thoughts of mad emperors and wine-fuelled orgies—and Douthat wisely separates himself from it. Instead, he references the French-American historian Jacques Barzun, who wrote that in a decadent society:

The forms of art as of life seem exhausted, the stages of development have been run through. Institutions function painfully. Repetition and frustration are the intolerable result. Boredom and fatigue are great historical forces.

In neat and well-argued sections—“Stagnation,” “Sterility,” “Sclerosis” and “Repetition”—Douthat argues that Western societies have grown fat on materialism but have withered in spirit. Some of his targets, like porn and drugs, are predictable bugbears of traditional conservatism. But Douthat avoids crankier right-wing arguments—such as that Pornhub and pot smoking turn nice young men into killers—in favour of the Huxleyesque thesis that such pleasures offer soporific escapism from loneliness and despair in atomised societies.

Douthat is not just concerned with so-called “moral” issues. The first section of the book, though heavily reliant on Tyler Cowen’s The Great Stagnation, elegantly argues that technological innovation has become less revolutionary. Someone who travelled from 1940 to 1980 would be awestruck, for better and for worse, by the scale of technological change. Someone who travelled from 1980 to 2020 would be impressed by the Internet and the smartphone but would find, in general, smaller, faster and more powerful variations on technology that they already had. Perhaps this is no bad thing—who wants superintelligent AI, after all?—but the progress that we have enjoyed has made us terribly reliant on continual advances to close the “ingenuity gap” between our abilities and the problems they have raised.

This is all journalistically effective, and as social science it is blessed by a cheering appreciation for the simple, powerful explanation over the enchanting speculative fantasy. Commentators have a weakness for inventing grand ideas to explain the fall in birth rates, for example, that happen to dovetail with their own ideological ambitions. It is feminism! It is neoliberalism! Douthat rightly observes that it has a lot more to do with the invention of the condom and the pill.

Two obvious questions to ask about this “decadence” are “what is wrong with it?” and “what should be done about it?” Douthat is admirably willing to admit that many of its features could be welcomed. “Complaining about decadence,” he writes:

…is, almost by definition, a luxury good—a feature of societies where the mail is delivered, the trains and planes are running on time, the crime rates are relatively low, and there are plenty of entertainments at your fingertips.

He could have gone further! We have all been anxious about coronavirus, but victims of the Spanish Flu, never mind the Black Plague, would have found our fears downright hysterical. We have all lamented the horrors of Middle Eastern wars but Steven Pinker is not mistaken in arguing that modern peace is much more commonplace than modern war.

Still, as Douthat argues, decadence has victims whose suffering is less obvious. The isolated victims of family breakdown and the hopeless addicts of the opioid crisis are generally out of sight but no less real because of it. I would add the livestock being tortured to sustain our appetite for cheap animal products, the millions of fetuses created and killed to sustain sexual choice, and the Congolese men and women who were massacred as Westerners enjoyed their mineral products. Conservatives can and should lament the spiritual ugliness of modern art, architecture, pornography, and advertising, but the genuine violence that liberal consumerism has depended on should also not be ignored either.

What is to be done about this? Douthat observes that Patrick Deneen’s Why Liberalism Failed is “like most such texts…stronger on critique than prescription.” His book, as he would doubtless agree, is no exception.

Perhaps there is little to be done about it. Oswald Spengler’s busy ghost haunts this book, like so many others, and the German sage saw the decline of the West as an inevitability. Douthat is rightly dismissive of the idea that Trump and Brexit represented a radical populist break from the status quo. Correctly qualifying his judgement with the observation that Trump could change everything, and for the worse, with ill-considered wars, he nonetheless argues that his presidency has featured virtual radicalism and actual weakness and sclerosis. Douthat is also justly sceptical of techno-utopianism. Echoing the writer Micah Meadowcroft, he argues that we should be “better stewards of our planet” before aiming outwards.

Douthat grants that catastrophe could strike decadence, such as if climate change leads to famine and conflict and northwards migration leads to strife and social breakdown. His more optimistic moments are considerably weaker. In one curious passage he argues that there could be a “Euroafrican” renaissance but his evidence amounts to the existence of Cardinal Robert Sarah and, of all things, the Marvel film Black Panther. Cardinal Sarah is a fantastically impressive man who does indeed remind us of the universality of the Catholic Church, but he is one man. Black Panther, meanwhile, is a superhero film. I am not seeing the seedlings of such a renaissance yet.

At the end of the book, with what strikes me—possibly unfairly—as embarrassment, Douthat writes that he would be “a poor Christian if [he] did not conclude by noting that no civilization—not ours, not any—has thrived without a confidence that there is more to the human story than just the material world as we understand it.” I see Douthat’s problem. He does not want his non-Catholic readers to be turned off by excessive religiosity, still less to think he is rationalising faith-based prejudice. All of his diagnostic arguments are scrupulously secular, and his argument for renewed faith ends with the slightly underwhelming claim that it “shouldn’t surprise anyone if decadence ends with people looking heavenwards.”

Frankly, as much as I enjoyed and agreed with most of The Decadent Society, I would have welcomed hotter, fiercer religiosity. One assumes that as one of the West’s more prominent Catholics Douthat thinks religious revival, however improbable, would be the answer to alienation and sterility, so he should have made that case. I might not have agreed, and others might have been outraged or disdainful, but it would have made the book more challenging and invigorating. After all, features of Western societies that non-religious people may find sad or dangerous, like reductive materialism, family breakdown and abortion, seem dramatically worse from a Catholic perspective, so philosophical neutrality is futile. Ironically, in what I suspect are his attempts to not be pigeonholed, Douthat has not quite spread his wings.

If this book does not entirely transcend the conservative complacence that I wrote of in my introduction, though, then it transcends it in its moral seriousness, its argumentative rigour and its avoidance of cheap, attractive yet simplistic solutions. If some future man or woman—or intelligent being of a different kind—stumbles across the book decades or centuries from now they will be richly informed about the age that we inhabit. One can only hope there will be cause to look upon us kindly.