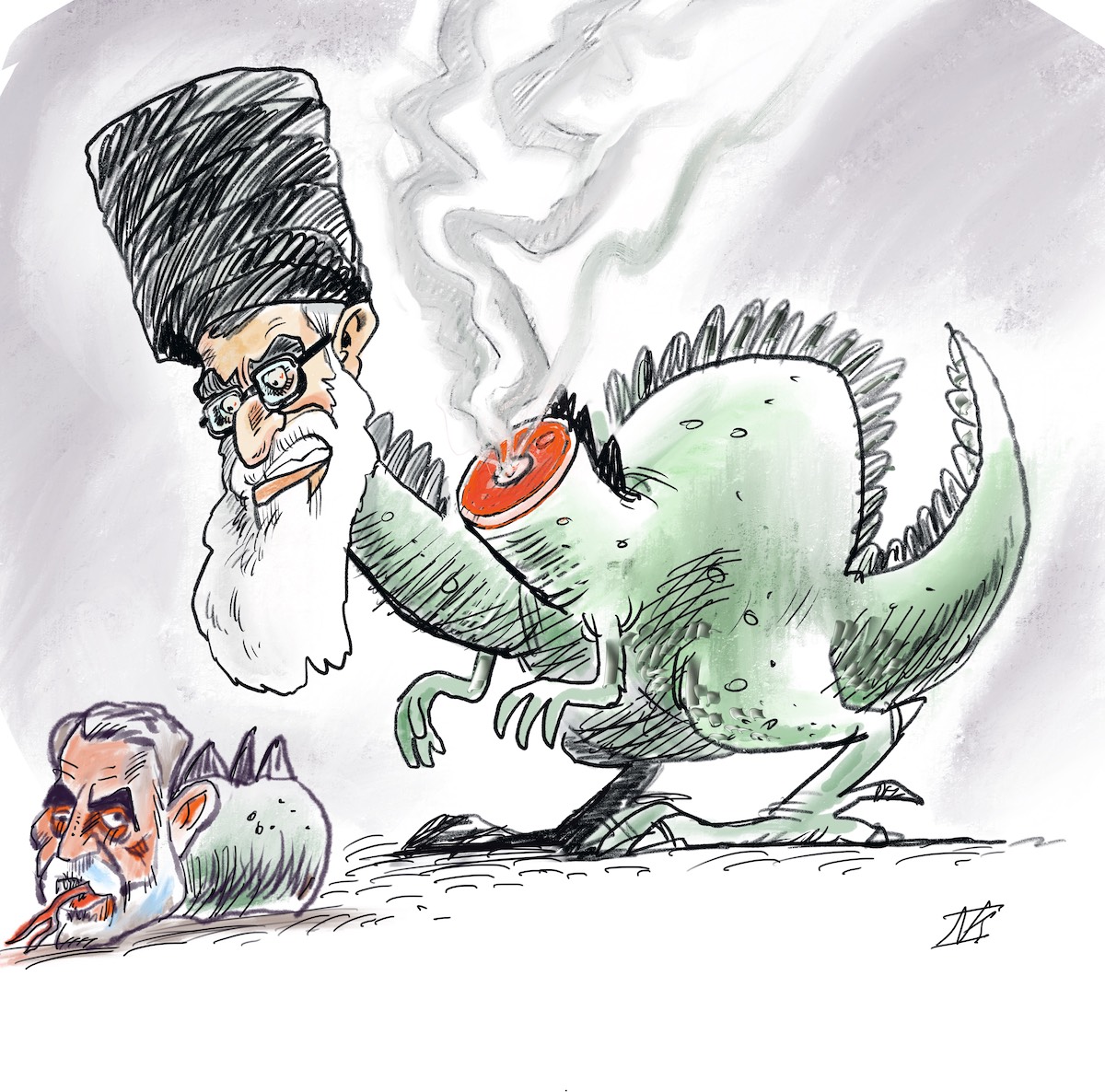

Ayatollah Khamenei

How Long Before the Regime Falls in Iran?

Opposition to the regime is not just to be found in the clergy. It is wide and deep but also unfocused.

The death of Iranian Quds Force commander General Quassem Soleimani has produced some truly bizarre media coverage. Some Western media outlets are framing Soleimani’s death as the loss of a deeply beloved hero, such in this January 7th episode of the New York Times The Daily podcast. The podcast spends more than 20 minutes describing how Soleimani was a beloved totem, a living security blanket that Iranians believe protected Iran from instability (by fostering instability in Syria, Iraq, Lebanon, and Yemen, apparently). The closest thing in the podcast to an acknowledgement that Soleimani led a group of armed thugs that viciously suppressed dissent in Iran, including turning their guns on Iranian protestors less than two months ago, was a single sentence in the podcast: “To be clear, there are plenty of Iranians who did not love or respect Soleimani.”

“Plenty” seems an inadequate way to characterize the majority of Iranians. Seventy-nine percent of Iranians would vote the Islamic Republic out of existence if given a chance, according to one poll. Yet somehow that torrent of anti-regime, anti-Soleimani sentiment was not deemed fit to discuss when describing how Soleimani’s death was received in Iran.

Even more oddly pro-regime were stories blaming U.S. President Donald Trump for the shooting down of the civilian airliner. The downing has since led to ongoing anti-regime demonstrations all over Iran, in which protestors are ripping down posters of the allegedly beloved Supreme Leader and Soleimani, while pointedly walking around U.S. and Israeli flags that the regime has painted on the ground to encourage people to tread on them. Iranians have limited ways to challenge pro-regime propaganda, but deliberately not disrespecting the U.S. flag is one.

Preference falsification

Far too many of those covering the Iranian reaction to Soleimani’s death never ask whether the crowds walking the streets in Tehran as part of Soleimani’s funeral cortege had reasons for being there that had nothing to do with mourning.

As the Iran analyst at the non-partisan Foundation for the Defense of Democracies, Alireza Nader, told me, “The regime is good at coercing crowds through threats and intimidation.” Which means media outlets using crowd size as a metric to gauge support for the regime should try to learn how many people are there of their own free will, and how many are, for example, Iranian government employees given the day off from work and ordered to show up. That’s a tactic the regime routinely uses to whip up anti-American demonstrations. Duke professor Timur Kuran describes this mechanism in his book, Private Truths and Public Lies, which he calls “preference falsification, i.e. the act of misrepresenting our wants under perceived social pressure.”

People will falsify their preferences about what they really believe for a variety of reasons ranging from a simple desire to be polite, all the way up to a wish not to get shot. Or to paraphrase Alireza Nader from Twitter, “All the Iranians celebrating the death of Soleimani had to do it at home.”

Many clerics loathe the Supreme Leader

With pro-regime, pro-Soleimani parades being followed by anti-regime protests and riots, it is easy for outside observers to be confused about the true level of support for the regime, and how long it’s likely to persist. The answer, as with most everything to do with Iran, is complex and confusing, even for people who have been following Iran for years, as I have.

If, for example, you assume that because Iran is a theocracy, the majority of the other Ayatollahs support the Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Khamenei, you’d be wrong. He is quite unpopular among the Shia clergy. (I explained why in greater detail in this piece for Foreign Policy.) But the reason his clerical support is weak is that the whole ruling system he’s at the center of, which translates as “the Rule of the Islamic Jurist,” is considered a scam by most Shia clerics. Until Khomeini seized power in 1979, most Shia clerics believed—and many still do, including Grand Ayatollah Ali Sistani in Iraq—it is not a religious leader’s place to wield temporal power, but to provide wisdom in the form of clerical rulings, and to be a marja, a spiritual guide who lives life in a manner worthy of emulation. Other Ayatollahs have spoken out against the excesses of the “Rule of the Islamic Jurist” including Grand Ayatollah Montazeri, who was once Khomeini’s designated successor, but who was placed under house arrest and died there.

Which brings us to the other reason why most Ayatollahs don’t like the Supreme Leader. When Khamenei was selected as the successor for Khomeini he was a mid-ranking cleric. Think a monsignor in the Catholic church, slightly above a parish priest, but not by much. Then there’s the fact that Khamenei’s claim to be a bona fide Ayatollah is a bit dubious. The clerical rank of Ayatollah is granted by your peers after they have examined your collected clerical rulings. Khamenei tried to pass that test with a collection of uninspired rulings circulated among the Shia community in Pakistan that hadn’t even been published in Iran. Imagine how popular you’d be in the Catholic church if you promoted yourself from priest to Pope.

Khamenei retains the grudging support of much of the Shia clergy, which largely amounts to agreeing to stay quiet and not interfere, by the simple expedient of paying them off to the tune of hundreds of millions of dollars a year. This made the news when an Iranian budget document was released in late 2017 and immediately set off demonstrations because spending on items like infrastructure was being cut while clerical subsidies increased.

An opposition without leaders

Opposition to the regime is not just to be found in the clergy. It is wide and deep but also unfocused. That is no accident. If there is one thing police states are great at, it is making sure there are no credible opposition leaders to rally around.

The last two major “opposition leaders” currently alive in Iran are Mehdi Karroubi and Hussain Mousavi. Both have been under house arrest for a decade after trying to lead anti-regime protests in 2009. As opposition leaders, they have major flaws, including advanced age, but more importantly, they are tainted by association with the regime. Both served in the government of Ayatollah Khomeini just after the 1979 Revolution. During this time, thousands of Iranians were designated as “enemies,” including Marxists, intellectuals, and supporters of the deposed Prime Minister Mohammed Mosaddeq. These secular allies, who had helped Khomeini overthrow the Shah, were immediately stabbed in the back once the Shah was gone as part of Khomeini’s consolidation of power.

Outside of Iran, opposition to the regime has two homes.

The first is Crown Prince Reza Pahlavi, living in exile in the United States. Several sources I spoke to suggested that Pahlavi has a deep well of support to draw on. But Pahlavi is currently sitting on the sidelines and not trying to rally opposition to the regime. This lack of activity may be one reason Pahlavi is still breathing. Iran hasn’t been shy about using assassins to take out opposition figures, including a wave of killings in Europe in the 1980s, and at least one in the U.S.

The other is the Mujahedeen-e-Khalq, or MEK, a militant political organization with roots in Marxism dedicated to overthrowing the regime. The MEK has an effective propaganda machine, plenty of money, and ties to the American government. Several years ago, it not only managed to get itself off of the State Department’s terrorism watch list, a place it had earned by planning attacks against Americans in the U.S., but got Republican luminaries Rudy Giuliani and John Bolton to speak at MEK-sponsored rallies.

The main problem with the MEK is that everyone not on the MEK payroll considers the group to be a cult.

That stems, in part, from having taken money from Saddam Hussein during the Iran-Iraq war, and then fighting on Saddam’s side. Now that Saddam has gone, the MEK is reported to be taking stacks of cash and gold from the Saudis, whom many Iranians hate even more than they hated the Iraqis during the Saddam era.

It’s not about oil. It’s about water.

One man I spoke to believes he knows what will ultimately fire up the opposition to the regime: water. Iran is running out, fast. Nothing to do with climate change, and everything to do with the sort of epic state mismanagement reminiscent of China’s “Great Leap Forward.”

I learnt this from Nikahang Kowsar. Dedicated Iran watchers know Kowsar as an outsized critic of the regime, a voice amplified by his skill as a political cartoonist. If you’ve ever seen a cartoon about Iran imbued with a brilliant, brutal sarcasm, odds are Kowsar drew it. His work has appeared in prominent outlets around the world, but before he ever picked up his cartoonist’s pen he was a geologist. He was ultimately forced to leave Iran after being imprisoned and interrogated for his cartoons mocking the regime. But before that happened, he told the so-called “moderate” president of Iran, Mohammed Khatami, that Iran’s water management practices were going to eventually push the regime off a cliff. Kowsar believes his warning, delivered almost 20 years ago, is about to become a reality. Iran is headed for a drought of biblical proportions, according to him, one that is already underway if you look at rural migration patterns. And continuing regime mismanagement is making it worse:

I believe that Iran is going to face a dire situation in the next few years and it’s not going to be sustainable. Based on the numbers that the government just published last year, by 2013, when Rohani became the president, we had 12 million people living in city margins. In 2018, the number rose to 19.5 million. That means seven-and-a-half million in just five years.

Kowsar asserts the people moving to the cities—shantytowns and slums, for the most part—are rural people who can no longer work their land as they’re running out of water. He estimates that Iran has an annual water deficit of close to 20 billion cubic meters of and is making up the shortfall by drawing down the aquifers at a terrifying pace:

Iran has lost more than 85 percent of its groundwater resources the last 40 years. The population has gone from 35 million to 84 million. So, you have more consumers, less water and that means less food, less opportunity. So, nothing is sustainable.

Kowsar went on to explain how the regime created the looming water crisis. One of the first things that happened when the Shah fell is the regime threw out his sustainable water management programs, but it did not stop there. The Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) that Soleimani helped run is not merely a paramilitary organization; it’s also a commercial conglomerate that owns, among other things, the giant construction company, Khatam-al Anbiya, which makes a lot of money from building dams. The problem is, building a lot of dams can be stupid water management if you are living in a hot, dry environment where keeping water above ground leads to massive losses from evaporation, instead of letting it stay underground in the cool aquifers, where it does not. The other thing the dams do is prevent rivers and other bodies of water from recharging the same aquifers Iran is drawing down.

All the regime’s guns won’t matter when nobody has any water, and the Iranian masses recognize that it is the regime’s fault. Iran’s Minister for the Environment, Issa Kalanatari, has admitted that the country’s water woes are self-inflicted.

Kowsar says he is a friend of Crown Prince Reza Pahlavi, noting he has gone with the Prince to brief U.S. lawmakers like Senators Ted Cruz and John McCain in the past. According to Kowsar, the Crown Prince is surrounded by a coterie of advisors, with younger advisors begging the Prince to take more aggressive action to rally opposition to the regime, and older advisors counseling inaction and caution. To date, the older advisors seem to be winning, per Kowsar.

The Crown Prince broke a years’-long silence in a speech about Iran at the conservative Hudson Institute in Washington, D.C. on January 15th, 2020. It was live-streamed on YouTube and watched by about 1,300 people. Pahlavi listed the regime’s historical sins and cast it as absolutely unredeemable, not worth negotiating with. He called on foreign governments to stop supporting the status quo merely because they fear chaos in the region, and for a policy of maximum pressure to continue. He suggested Iranians start forming political parties and preparing for the succession.

But when asked about how the regime will go about relinquishing power when it shows all the signs of wanting to keep it, he sidestepped the question. He said there had to be planning for what comes next, not just hope for regime collapse. But he didn’t say who should be doing this planning. Those hoping Pahlavi’s speech would result in specific policy proposals and/or calls to action were disappointed.

Will blood run in the streets?

Even if the regime manages to stave off the looming water crisis, Kowsar is worried about blood running in the streets. “The people I’m talking to in Iran, especially the nationalists, they want just one thing: revenge on the regime,” he says.

Kowsar was not the only Iranian I spoke to worried about what Iran may look like if average Iranians, sick of 40 years of regime exploitation, finally indulge the urge for retaliatory violence. I spoke with former Iranian diplomat Dr. Mehrdad Khonsari, who used to run a small London-based dissident group, The Green Wave, and now heads a think tank based in France called the Iranian Centre for Policy Studies. Like Kowsar, Khonsari talks to many people in Iran, including current members of the regime. Khonsari is concerned that as the regime moves closer to collapse, which seems inevitable, Iran could quickly descend into a bloodbath unless something like a South Africa-style Truth and Reconciliation Commission is established to manage the transition.

Khonsari may well be right, but the trick, of course, is how to persuade angry Iranians to negotiate with the regime that has been repressing them. Nobody I spoke to had a good answer. Khonsari’s view is that if there is no safe exit path for senior regime figures they’ll have no choice but to cling to power until the bitter end. Khonsari believes the best hope of a peaceful transition is if some members of the regime negotiate a withdrawal, in which they’re allowed to escape punishment, and keep at least some of the fruits of their corruption. Otherwise, why voluntarily relinquish power?

Khonsari also believes one should not dismiss figures like Mehdi Karroubi and Hussain Mousavi. While the two men under house arrest do have a troubling past, for the last 10 years their identity has been that of men who tried to stand up to the regime during the contested 2009 presidential elections. Khonsari believes the Iranian youth who never experienced the excesses of the regime in the 1980s and so don’t have grudges to bear will value that defiance.

When the lying stops

Assessing the opposition to the regime is difficult because it’s hard to know how much preference falsification is going on. It seems fitting to give Professor Kuran the last word—as a professor of economics, political science, and Islamic studies, he has a Venn diagram of expertise that makes him well qualified to comment on the potential for regime change in Iran. He sent me the following comment via email:

A regime sustained by preference falsification cannot survive indefinitely. In Iran, everyone now understands that the theocracy is widely hated. But few Iranians oppose it openly, because this exposes them to brutal retaliation. They will do so only if something sparks a critical mass of open dissenters. At that point, a cascade will make the growth of opposition self-enforcing. In a short time period, millions can come out of the closet, making it impossible for the theocracy to continue governing. There are plenty of potential flashpoints. The economy is in shambles. Sooner or later, people with little to lose will say ‘enough is enough.’

Art Keller has covered Iran issues in and out of government for 20 years. His novel about the CIA and Iran is Hollow Strength. You can follow him on Twitter at @ArtKeller