Education

Demoted and Placed on Probation

One young man said to me, “How did you get tenure?” When I said that I didn’t have tenure he said, “Good! Because you’re not going to get it.”

It all started in June 2018, when Quillette published my article, “Why Women Don’t Code,” and things picked up steam when Jordan Peterson shared a link to the article on his Twitter account. A burst of outrage and press coverage followed which I discussed in a follow-up piece. The original article was one of the ten most read pieces published by Quillette in 2018, and continues to generate interest. A recent YouTube video about it has been viewed over 120,000 times, as of this writing:

In his tweet promoting my article, Peterson took issue with one of my claims. I had written that I thought I could survive at the Paul G. Allen School of Computer Science and Engineering where I work. Peterson disagreed:

As it turns out, Peterson was right. My position is not tenured and when my current three-year appointment came up for review in December, I was stripped of my primary teaching duties and given a highly unusual one-year probationary appointment. The administration insists this decision had nothing to do with the controversy generated by my article. But as I will explain, that seems highly unlikely. As one faculty colleague put it, an “angry mob” has been after me ever since my article came out.

The Intro Classes

In 2005, the University of Washington hired me to redesign their two introductory computer science classes. I developed two highly successful courses that have over 4,500 enrollments combined per year and are among the most highly rated 100-level courses at the University of Washington. In a recent internal survey, over 80 percent of the students agreed that the assignments increased their interest in computing and showed them how useful such knowledge can be. Teaching at this scale is a massive undertaking and for the last 15 years I have been responsible for overall management of the staff, instructors, and TAs who provide this service.

In response to my Quillette article, a group of graduate students in the Allen School filed a grievance against me with their union. The university agreed to several of their demands, including that, “A group of (mostly senior) faculty will review the introductory programming courses to ensure that they are inclusive of students from all backgrounds.” A working group was formed and it produced a set of recommendations. These included:

- A relaxation of grading on coding style.

- Allowing students to work together in a group for part of their grade instead of requiring them to complete all graded work individually.

- Training for TAs in inclusion and implicit bias.

- Review of all course materials for inclusiveness. For instance, of a lecture that involves calculating body mass index (BMI) using guidelines from the National Institutes of Health, the report noted that it “seems insensitive to present students with a program that would print out that some of them are ‘obese’ while others are ‘normal.’”

- A reduction in the amount of effort expended pursuing cheating cases by 50 percent even though there has been no reduction in cheating cases.

The report also recommends that courses incorporate inclusiveness best practices as outlined in an Allen School document. These include:

- The addition of an indigenous land acknowledgement to the syllabus.

- The use of gender-neutral names like Alex and Jun instead of Alice and Bob.

- The use of names that reflect a variety of cultural backgrounds: Xin, Sergey, Naveena, Tuan, Esteban, Sasha.

- An avoidance of references that depend on cultural knowledge of sports, pop culture, theater, literature, or games.

- The replacement of phrases like “you guys” with “folks” or “y’all.”

- A declaration of instructors’ pronouns and a request for students’ pronoun preferences.

Most of these suggestions seem to rely on the notion that undergraduates are delicate. While I agree that we must be careful to ensure that all students feel welcome and respected, we should be helping our students to become antifragile. So I will continue to use the BMI example, I will maintain high standards for grading, and I will continue to pursue cheating cases vigorously. I will continue to say “you guys” and to make occasional cultural references. In the case of pronouns, I have always made an effort to accommodate requests from transgender students, but I refuse to use words that are not part of the English language.

It is the prerogative of the faculty to change the intro classes if they so choose. I understand that inclusive teaching is popular now, so it makes sense that others would want to move them in that direction. Even though this review was precipitated by my Quillette article, it is not in itself evidence that I am being treated differently on account of my political beliefs.

My Probation

What I find difficult to accept is that I was reappointed for just one year. The Allen School often hires adjunct and temporary lecturers for only one year, but that isn’t how it routinely treats lecturers with a regular appointment. In the 15 years I have been part of the school, I am the first regular lecturer to be offered less than a three-year extension.

The administration claims that my one-year reappointment is part of a more general change in the management of the intro classes, but that doesn’t make sense. They are perfectly within their rights to take management of intro away from me and even to forbid me from teaching intro classes. So why are they threatening my job security as well? I am able to teach a wide range of classes. I have mostly been teaching in intro recently because there have not been enough teaching cycles available for me to teach other things, but I have taught five different courses outside of intro. For each of the last seven years, the Allen School has been unable to hire enough lecturers to meet our needs, despite undertaking a nationwide search.

The one-year reappointment is also odd given my faculty rank. I was the first lecturer in the College of Engineering at UW to be promoted to the rank of principal lecturer. The faculty code indicates that the normal period for reappointment for a principal lecturer should be at least three years. The administration had to obtain special permission from the provost to make such a short appointment. It is also perhaps worth noting that I am the only current member of the faculty in the Allen School who has won the Distinguished Teaching Award, which is the highest award given for teaching at UW.

A faculty colleague told me he believes I am being fired for my political beliefs. He said it became clear during the meeting at which my reappointment was discussed that quite a few people wanted me to be summarily dismissed. Others said it was unacceptable to fire me outright. In the vote that was taken, faculty were asked to choose one of three options: no reappointment, a one-year reappointment, or a three-year reappointment. So the one-year appointment was the middle ground that allowed faculty to punish me without taking the most drastic available step just yet. I have the impression I am expected to feel grateful.

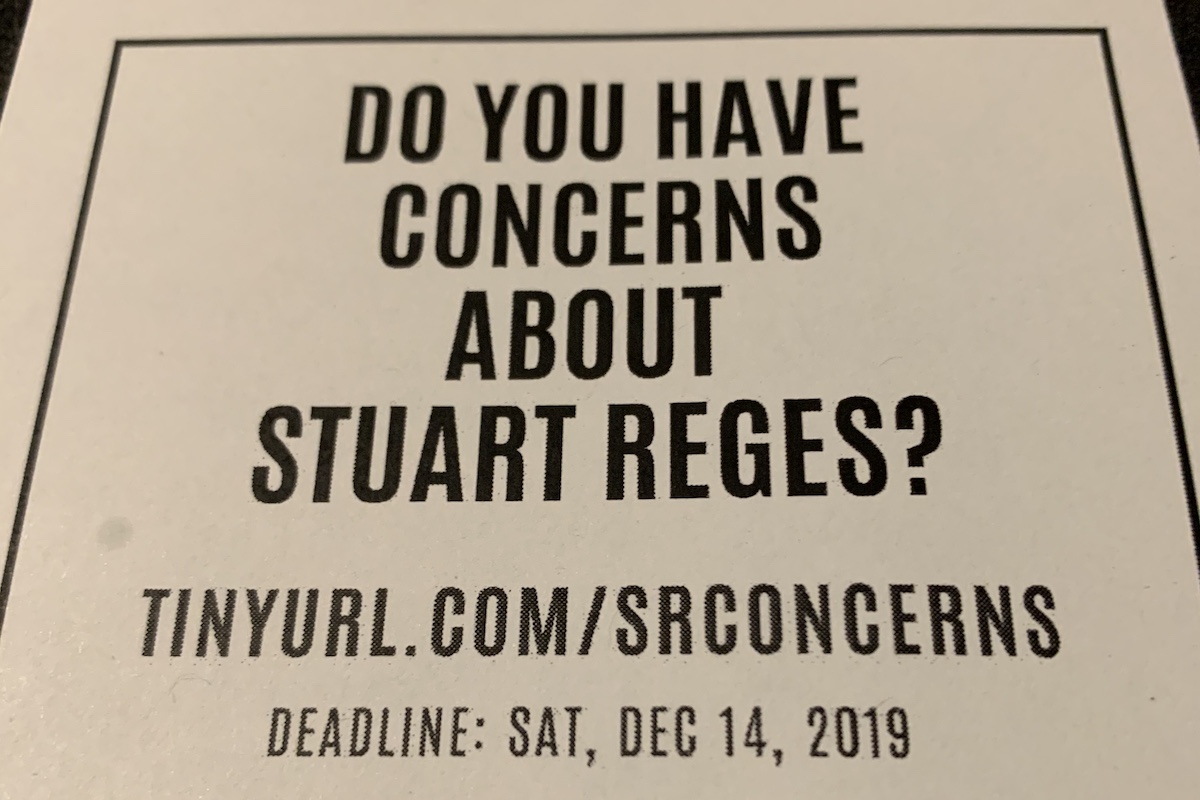

The students weighed in on the decision as well. A poster was plastered throughout the undergraduate labs and the student union encouraging students to visit a web address if they wished to express concern about my possible reappointment (reposted here). Critical student testimonies were collected in a letter to the dean urging her not to reappoint me.

Heterodox Teaching is Off Topic

Nor have my teaching evaluations slipped in recent years. I am, however, spending more time thinking about how to encourage viewpoint diversity. I have joined Heterodox Academy and have met with local members of the group. I attended the 2019 Heterodox Academy Conference and the 2018 faculty conference for the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education (FIRE). As part of the reappointment process, I was asked to describe what I’ve done and where I see myself going. I mentioned that I would like to expand my work on heterodox teaching.

The faculty members who reviewed my reappointment materials reported that they were “surprised” that I would mention my work in this area. They said that I have a right as a citizen to do this, but they also pointed out that the Allen School leadership had felt the need to respond publicly to my Quillette article (presumably a negative). They announced that my work in this area was not related to my professional responsibilities and should therefore be considered “off topic” and irrelevant to a review of my work performance and my consideration for reappointment.

This was particularly disappointing because I am doing some of my best teaching in this area. In the fall of 2018 I assigned Haidt and Lukianoff’s The Coddling of the American Mind as part of a seminar for honors students. I received my highest scores ever for this seminar (an average of 5.0 on a 5-point scale). Here are two representative comments from the student evaluations:

We were asked to share our personal opinions and the reasoning behind them, without any fear of being shamed or irrationally responded to. This allowed for meaningful discussions to develop, and a level of vulnerability in answering questions and discussing various topics that I have experienced nowhere else in the university setting.

This class really made me think about the way we have learned to perceive the world, especially in regards to tolerance [of] conflicting viewpoints. It made me realize that although we sometimes advocate for diverse opinions, we often shut down a certain group of opinions, which is hypocritical and very dangerous. I think that in order to learn and grow, we have to hear viewpoints that we disagree with, which is unfortunately not something that happens often enough in our society.

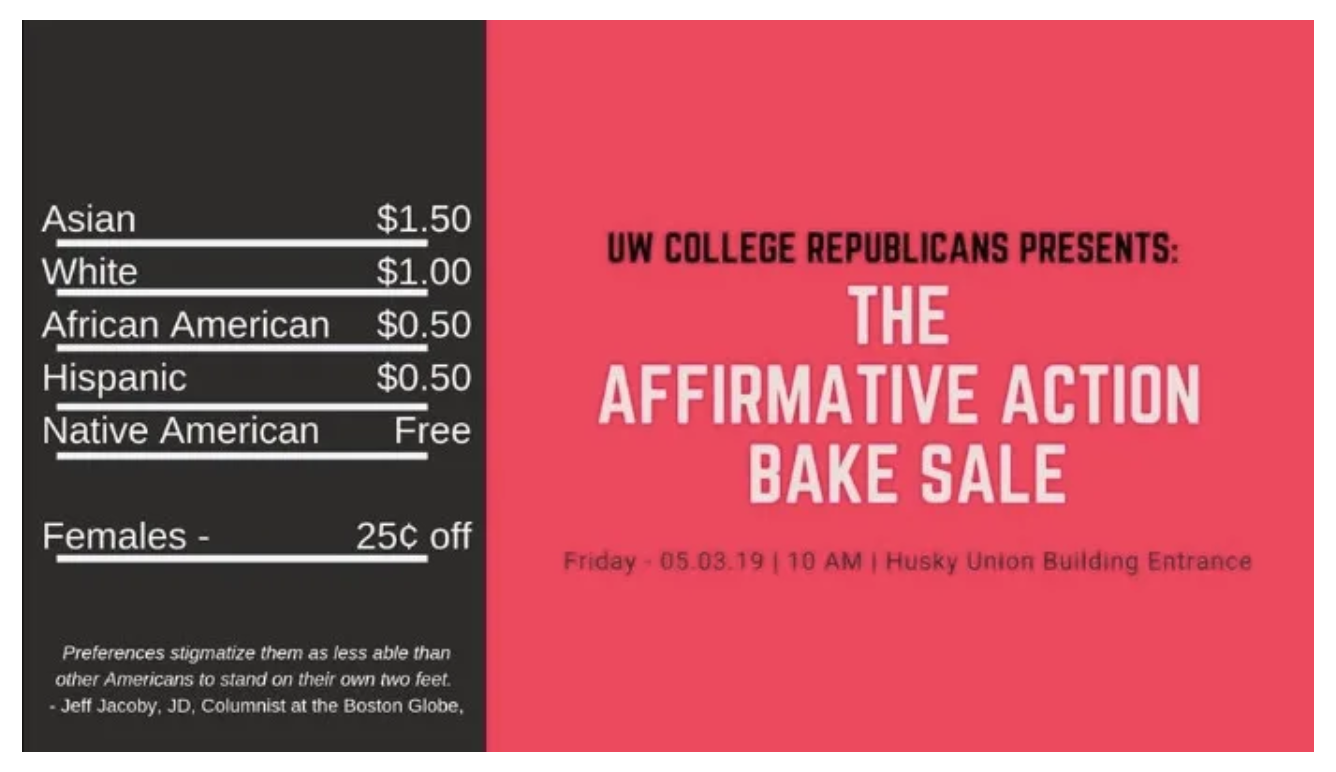

The Affirmative Action Bake Sale

An event in the spring of 2019 provides an illustrative example of the mob mentality at the university. The state legislature was considering an initiative to reinstate affirmative action. In response, the UW College Republicans organized an affirmative action bake sale, at which cookies were sold to Asians for $1.50, to whites for $1, and to African Americans and Hispanics for 50 cents. Cookies were free to Native Americans. This kind of stunt has a long history on college campuses. It drew an angry response from students and police had a difficult time keeping the peace. One protestor threw a tray of cookies to the ground, but otherwise there was no violence.

I attended the event to see how it was received and ended up having an hour-long conversation with a young woman about race relations on campus. When I was able to speak to her directly, we were able to understand our different perspectives and how we came to different conclusions about the value of affirmative action. But she was also playing to a gathering crowd, inviting them to join her in condemning me. One young man said to me, “How did you get tenure?” When I said that I didn’t have tenure he said, “Good! Because you’re not going to get it.”

The Stranger published an article about the event which included photographs of my interactions with the young woman. I was quoted as saying, “I don’t see racism on campus,” and the article’s authors reported that the crowd laughed when a student retorted that this is because I’m white. But, as footage of our exchange captured by a local news team later confirmed, what I actually said was “I don’t see rampant racism on campus.” A small but important difference between a denial of ongoing racism and a disagreement about its prevalence.

A local conservative talk show host named Jason Rantz was at the bake sale and made his own recordings. In two articles about the event, Rantz posted a five-minute audio excerpt of my exchange with the young woman, during which we debated whether group identity is more important than judging people as individuals. Anyone interested in assessing the attitude I bring to these conversations can listen to that exchange and judge me accordingly. Nevertheless, the day after the article in the Stranger appeared, I received a message from the director of the Allen School which included this:

…in my opinion, this is not about freedom of speech, and it’s also not about affirmative action, on which there are obviously multiple views that could legitimately be debated and discussed. This is about your lack of sensitivity to minority students and your continued (and almost gleeful) denial of their experiences, which I find extremely regrettable and disappointing coming from somebody of your stature and experience.

He later told me that his judgment was based entirely on the misreported quote. He didn’t ask me what had happened. He didn’t ask if the quote was accurate. He simply concluded that I was insensitive to minority students. How he decided that I was “almost gleeful” is beyond me, but it indicates a reflexive disapproval among some my colleagues since the publication of my Quillette essay.

A few days later, a blogger identified as “Anonymous Husky” called for me to be fired in a Medium post entitled, “Why the UW Computer Science Department Can Do Better than Stuart Reges.” The article mentioned the bake sale, my Quillette article, and my protest against the war on drugs that led me to be fired from Stanford in 1991. It was emailed to every member of the computer science faculty and many of the undergraduate TAs I work with.

The New Closet

I spent New Year’s Eve of my senior year of high school in a hospital because I almost succeeded in taking my own life with a bottle of rat poison. I was a young gay person who couldn’t face telling people I was a member of that hated group known as “homosexuals.” Although it was a dark period, that experience provided me with a source of strength later in life. If I was so unacceptable that I thought it was better to be dead than alive, then what was to be lost by telling people what I really think? By the time I got to Stanford as a graduate student in 1979, I was openly gay. Not many people were at the time. When I started teaching at the university, I found that many gay people wanted to talk to me but almost always in private. They would tell me that they couldn’t afford to be as open as I was.

But even I felt the pressure to conform. In 1982, I applied for my dream job. The Stanford Computer Science Department was hiring someone to manage the intro courses. I was doing the job on a temporary basis, but they were looking to appoint a permanent staff member. Unfortunately, their search concluded just after the Stanford Daily published a full-page article I had written entitled, “On Being Gay: Feelings and Perceptions.” The chair of the department told me that they wanted to offer me the job, but that they had been embarrassed by my article. They wanted me to promise never to publish such an article again. I had an opportunity to be brave and refuse his request, but I didn’t. I said that I couldn’t make that promise but that I didn’t feel the need to publish any more articles any time soon. That was enough to get me hired. And I didn’t write any articles for the next three years until we got a new chair who told me I could publish whatever I wanted.

Over the course of my life, it has been astonishing to watch anti-gay sentiment reverse. Today, the people on campus who need to worry about expressing their ideas are conservatives and religious people. Now it is gays doing the punishing of anyone who opposes gay marriage, gay adoption, hate speech codes, and civil rights protection for gays. Everything old is new again. I’m once again having private conversations behind closed doors in my office with closeted individuals, but this time they are students, faculty, staff, and alumni who oppose the equity agenda. They are deeply concerned about the university’s direction, but they are also afraid of jeopardizing their current or future job prospects. They also worry about losing friendships and professional relationships. One faculty colleague described it as “mob rule.”

Stanley Fish describes this situation well in his recent book The First:

These students, often a minority, but a minority with a loud voice, tend to be wholly persuaded of the rightness of their views; they don’t see why they should be forced to listen to, or even be in the presence of, views they know to be false. They wish to institute what I would call a “virtue regime,” where people who say the right kind of thing get to speak or teach and those who are on the wrong side of history (as they see it) don’t.

As a result, I can’t bring myself to look down on the closeted individuals who offer me support behind closed doors. The threat is real, just as it was when I compromised my principles to get a job nearly 40 years ago.

I am concerned that people believe free speech is improving on college campuses when in fact things are getting worse. We have fewer overt examples of speakers being shouted down and disinvited, but now the censorship is going underground. Those who talk to me behind closed doors censor themselves because they know the consequences of speaking up. As the economist Timur Kuran has explained, this preference falsification is extremely dangerous because it prevents us from having the meaningful conversations necessary to find practical solutions to problems.

So I understand why many people will choose to stay silent. I did it myself aged 23 when I stopped writing articles about being gay so that I could be hired into my dream job. But I’m older now and although I don’t have what people call “fuck you money,” I have enough saved that I can afford to speak my mind. For the rest of you, remember Jordan Peterson’s admonition: “Watch what you say. Or else.”