Must Reads

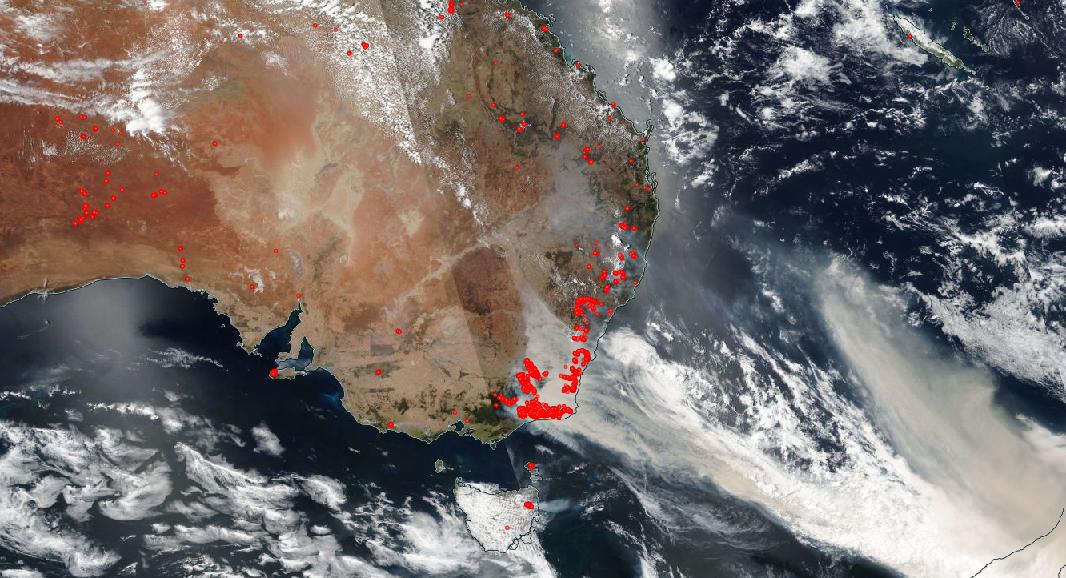

Lessons from Australia’s Bushfires: We Need More Science, Less Rhetoric

A more aggressive use of controlled burns might have given firefighters a chance to control this season’s bushfires.

· 8 min read

Keep reading

The Soft Disinformation Contagion

Jorge Iniesta Cases

· 7 min read

The United Nations Is Going Broke

Brian Stewart

· 8 min read

Iran’s Risky Gamble

Benny Morris

· 12 min read

Out on the Wily, Windy Moors...

Charlotte Allen

· 20 min read

Letters to the Editor

Quillette

· 3 min read