Activism

Science Fiction Purges its Problematic Past

Instead, as speculative fiction becomes more diverse, the sense that it must be corrected grows, and author and art are evaluated together.

Since 1991, the James Tiptree Junior Award has been given annually to a work of “science fiction or fantasy that expands or explores our understanding of gender.” The award was founded by two women science fiction writers, Pat Murphy and Karen Jay Fowler. From next year, it will be called the Otherwise Award.

James Tiptree, Jr. was the pseudonym of Alice Sheldon. Born Alice Bradley in 1915, she travelled the world with her parents as a young child. In 1940, after a brief unhappy marriage, she joined the women’s Army Auxiliary Corps and worked in intelligence. She married Huntington “Ting” Sheldon in 1945, and in 1952 they both joined the CIA. She later earned her doctorate and took up writing. She wrote short stories and novels, but it is the former that stand out as truly remarkable. With prose as subtle and precise as the most refined literary fiction, she penned imaginative tales like “Houston, Houston, Do You Read?” and “The Girl Who was Plugged In,” which became classics of science fiction and also important works of feminist fiction. Later in her life, she suffered from heart troubles and depression. Her husband went blind. She recorded in her diary in 1979 that she and her husband had agreed to a suicide pact if their health worsened. In 1987, she shot her husband, called her lawyer and told him that they had agreed to suicide, and then shot herself.

The award is being renamed because of this suicide. Although the prize was founded to recognize fiction “exploring gender,” the current board of the award see their expanded mission to be to “make the world listen to voices that they would rather ignore.” The issue is that some of these voices have decided that Sheldon killed her husband because she was ableist (that is, bigoted toward the disabled). Sheldon’s biographer, Julie Phillips, has tweeted in response: “The question has come up whether Alice Sheldon (James Tiptree, Jr) and her husband Ting died by suicide or murder-suicide. I regret not saying clearly in the bio that those closest to the Sheldons all told me that they had a pact and that Ting’s health was failing.” Phillips has also changed her Twitter profile to include the sentence, “Biographer of Ursula K. Le Guin and of James Tiptree, Jr., who was not a murderer.”

But evidence and expert judgment are not sufficient here. Someone feels that Sheldon murdered her husband, and such claims must now be respected. Thus, the board reports, “We value the disabled writers and readers and artists and fans who support this award. Many of them—many of you—have told us that the Award’s current name holds negative, painful, exclusionary associations. So we’re changing it.”

Speculative fiction is fortunate to have a community of active readers and writers who do volunteer work of the kind the Otherwise Award board does. It is not a criticism of their sincerity or generosity to recognize that this renaming is a kind of erasure of Alice Sheldon. Consider the words of Sheldon’s biographer on her blog: “For myself, I can say that I first encountered Alice Sheldon through the name attached to the award, and that if the award hadn’t been called the Tiptree I might never have written the biography.” It is hard for writers—even relatively successful writers—to find an audience. Removing “Tiptree” from the award, and replacing it with the anodyne “Otherwise,” will discard an opportunity for many readers to first hear of James Tiptree, Jr.

Sheldon is not the only member of the speculative writing community to recently be re-evaluated. In 2019, Jeannette Ng won the John W. Campbell Award for Best New Writer. In what is emerging as a new tradition for those receiving science fiction awards, she gave an acceptance speech denouncing the genre’s failings. She targeted the eponym for the award:

John W. Campbell, for whom this award was named, was a fascist. Through his editorial control of Astounding Science Fiction, he is responsible for setting a tone of science fiction that still haunts the genre to this day. Sterile. Male. White. Exalting in the ambitions of imperialists and colonisers, settlers and industrialists.

John Campbell was the editor of the magazine Astounding Science Fiction (the name was later changed to Analog Science Fiction and Science Fact) from 1937 until his death in 1971. He had enormous influence over science fiction in his time, and published many of the most famous science fiction writers, such as Arthur C. Clark, Robert Heinlein, and Isaac Asimov. The award was named in his honor. After Ng’s diatribe, the award was immediately renamed the Astounding Award for Best New Writer. Prominent writers released statements in support of Ng’s speech. Arguments were made that Campbell might not be appropriate to represent contemporary writers, but no one addressed whether we should want a community where we call each other “fascist,” or why it was reasonable to treat being male and white (or, oddly, exalting in industry) as deplorable.

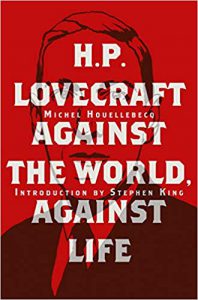

Other awards have been changed. The World Fantasy Award used to be a bust of the horror writer H. P. Lovecraft, designed by the famed macabre artist Gahan Wilson. After objections to the racism that Lovecraft expressed in his private letters and in some unpublished works, in 2016 the award was changed to a new sculpture of a sun setting behind a tree.

Cernunnos Press recently published a handsome new edition of Michel Houellebecq’s H. P. Lovecraft: Against the World, Against Life. The book is an example of how critics can confront problems like these with reason and care. Houellebecq addresses Lovecraft’s racism head on, drawing our attention to some of his most hateful expressions, like this one about the people he saw during his brief time living in New York: “The organic things—Italo-Semitico-Mongoloid—inhabiting that awful cesspool could not by any stretch of the imagination be call’d human.” Houellebecq recognizes this racism as a terrible flaw of Lovecraft, and he also recognizes that if it anywhere intrudes into Lovecraft’s fiction, it is to the detriment of that fiction. While drawing attention to his faults, Houellebecq also celebrates Lovecraft in a way that no scholar in the Anglophone world has (most writing on Lovecraft is apologetic for his prose style, estimating him as of limited talent). Houellebecq is most astute, and most full of praise, in evaluating Lovecraft’s ability to create a new mythology, something he recognizes as akin to Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s creation of the Sherlock Holmes stories. If we must be concerned with the author and not just the work, then Houellebecq’s book is an example of the balance that our criticism should achieve: we must recognize that the work is one thing, the author another. Literary criticism should not be a struggle session.

But this is not the spirit of our moment. Instead, as speculative fiction becomes more diverse, the sense that it must be corrected grows, and author and art are evaluated together. There is a notable asymmetry in this evaluation. Most fiction readers are women, and many fiction genres are dominated by women. Men who write romance novels or cozy mysteries must write under female pseudonyms, because the audiences for these genres will largely avoid books by men. In publishing, this is considered merely a demographic fact, and not an ethical failure of some kind. The attitude is very different towards science fiction. That for decades science fiction was mostly written, read, and published by white men is seen, at best, as something that must be denounced and aggressively corrected, and at worst as evidence that racism and sexism were the driving engines of this creative explosion. We do not single out other genres of fiction, or other art forms, for this kind of invective. We do not hear admirers of the golden age of jazz, for example, denounce the great composers of that era because they were nearly all African-American men. Louise Armstrong, Duke Ellington, Billy Strayhorn, Charlie Parker, John Coltrane, Thelonius Monk, Miles Davis, Wayne Shorter, and many other such men are honored for their genius, and we recognize their creations as a gift to humankind. Why not consider American science fiction in the twentieth century as a gift, instead of dismissing it as “Sterile. Male. White.”?

What we might call the commercial center of the speculative writing community has committed to diversity as a primary goal. Most agents and publishers now representing speculative fiction make explicit that they are eager to represent and publish diverse writers producing fiction on themes of diversity. In recent years, 90 percent of the nominees in the fiction categories for the Nebula Awards (the annual awards given by the Science Fiction Writers of America) were women. The president of the Science Fiction Writers of America has pinned a tweet to her Twitter account that reads: “It’s not about adding diversity for the sake of diversity, it’s about subtracting homogeneity for the sake of realism.” Everyone knows who counts as homogeneity and needs to be subtracted.

These organizations are member-driven non-profits; publishers and agents are private businesses and private individuals. Without reservation, we should support their right to make their own decisions, to rename their awards, to nominate the works they choose to recognize, and to promote the fiction and writers they want to promote. But there is a clear pattern now in these campaigns, wherever they occur. Victory is not followed by celebration, nor even a passing frisson of satisfaction. Instead, it leads to ever greater anger towards the vanquished and a search for new enemies, while the bar for outrage gets ever lower. Thus, we start out objecting to a bust of H. P. Lovecraft, and soon we are quashing one of our greatest feminist writers.

Why do those who remain silent while others denounce the legacy of Alice Sheldon not recognize that the outrage will eventually be aimed at them, or at their favorite writers? If fiction—and any accomplishment in publishing, editing, and promoting fiction—must be evaluated by applying ever-shifting ethical standards to the individual doing the work, then any work can eventually be deemed “problematic.” It will be as easy to denounce the most enlightened of the contemporary speculative fiction writers as it was to denounce John W. Campbell.

At its best, science fiction gives us a way to think about our time, the future we want to achieve or avoid, and our relation to technology. In one of Alice Sheldon’s most powerful stories, “The Women Men Don’t See,” a woman named Parsons and her daughter hire a pilot to take them to Chetumal. The plane crashes en route, and they are stranded with the pilot and a fisherman in the wilderness. The fisherman struggles to understand the women. The feelings and hopes and goals of Parsons are invisible to him, and all he can do is project his prejudices onto her. Understanding this, Parsons likens herself to a nocturnal animal, present but not genuinely seen. She tells the fisherman, “What women do is survive. We live by twos and threes in the chinks of your world machine…. Think of us as opossums…. Did you know there are opossums living all over? Even in New York City.” When an alien spaceship lands nearby and the group encounters an extraterrestrial explorer, the fisherman panics, but Parsons and her daughter beg the aliens to take them away. They would rather leap into the unknown than return to their life in America. Written with careful realism, the story is a masterful inversion of expectations and tropes. The fisherman tries to stop the women, but they leave Earth with the alien explorers. Later, drunk in a bar, he muses, “Two of our opossums are missing.”

We need to learn from Sheldon’s wisdom. Anyone can be an opossum now.