recent

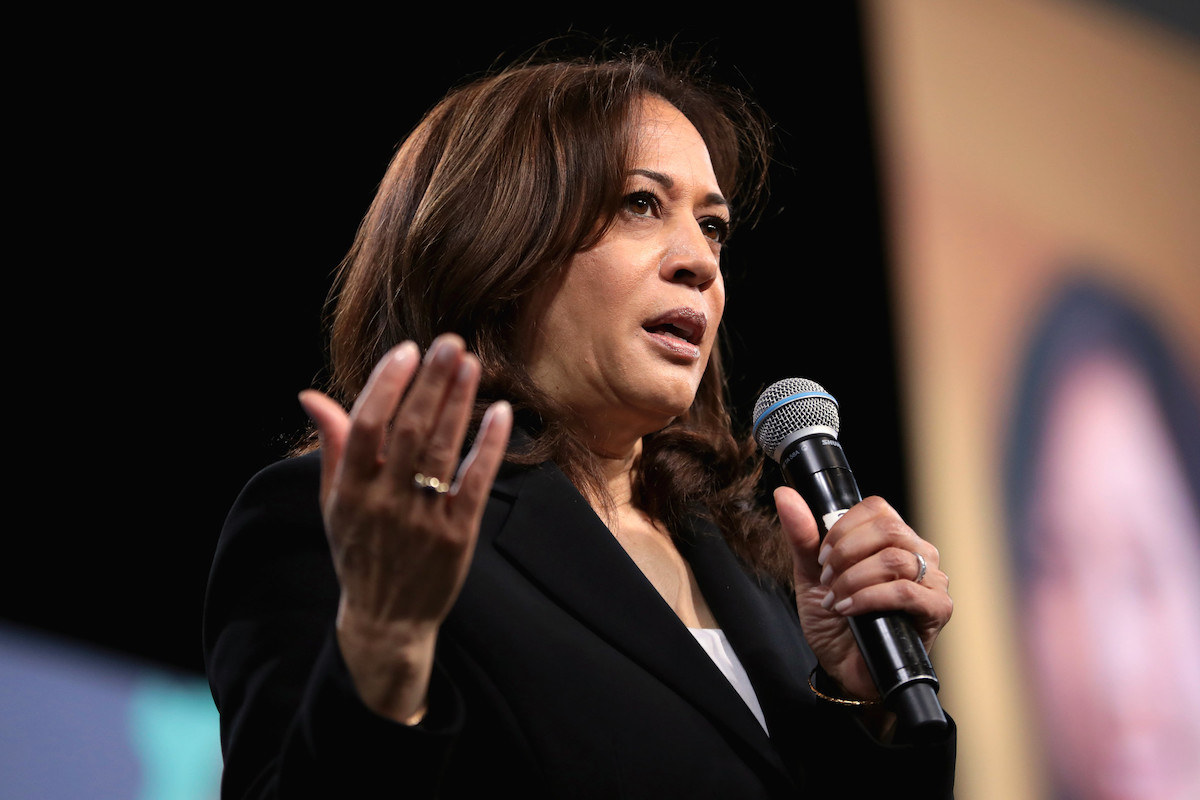

Why Has Kamala Harris's Campaign Fizzled?

The logic of a Harris candidacy rests on her coalition-building skills.

For Democrats, the current 2020 election cycle is perhaps the most important in modern history. For the party faithful, unseating Trump—a man Democrats consider to be the worst President in modern history—has become the overriding concern, even eclipsing the party’s lively policy debate. One rising star, and a politician many considered would give the President a run for his money, is the junior senator from California, Kamala Harris.

Superficially, Harris looks like the party’s dream candidate. She is a woman—an asset to a party animated by gender politics, concerns about diversity and still reeling from the #MeToo movement. She is also an ethnic minority (her mother is Indian, her father is Jamaican), another box ticked for a party which draws considerable support from non-whites. Her former life as a prosecutor, San Francisco district attorney and California state attorney would be a dangerous match-up for the unscrupulous Trump, who has spent more time than most avoiding a court room. Having been a senator since 2016, she is already a national political figure. She has also proved herself to be a fairly effective debater, being seen to best former Vice President Biden in previous encounters.

Despite these apparent pluses, Harris’ performance in the contest has so far been lacklustre. A tussle with the frontrunner Joe Biden in the second debate saw her reach 20 percent in one Quinnipiac poll, but the bump was short-lived. At the time of writing, Harris is once again languishing in single digits.

Things have only worsened for the Senator in recent days and weeks. Following the recent third round of primary debates, Harris emerged the most damaged of all of those on stage; decreasing her pool of potential voters more than any other of the candidates, particularly among voters who prize electability. Contrary to many post-debate takes, this is not necessarily down to nascent sexism among viewers, as Elizabeth Warren managed to improve her standing among those voters at the same time.

Some of these disappointments are to be expected. Harris is an ethnic-minority from a coastal city, so is almost lab-designed to perform poorly in the first two primary states of Iowa and New Hampshire. As a candidate who polls well among the black community, her first opportunity to enter the top-tier of candidates rests on a stellar performance in South Carolina, a state with a sizeable African-American presence. But even there her polling is only marginally better than the national average. In her home state of California, it is no better. So what went so wrong?

The logic of a Harris candidacy rests on her coalition-building skills. Primarily her ability to consolidate the African American vote, a feat that, so far, only Joe Biden has come close to achieving. A survey by the black Economic Alliance found that although black voters were relatively enthusiastic about Harris (53 percent) and the other leading African-American in the race, Cory Booker (43 percent), the same survey showed Biden was far ahead of the pack (76 percent). Like many politicians, Harris and her team appear to have learned the wrong lessons from the Obama years, believing black voters are more likely to support black candidates than they actually are.

Harris’s previous life in California as a tough-talking hard-on-crime politician has won her few favours in the Democratic Party of 2019, which is increasingly radical on issues of immigration, crime and race—and more cognizant than ever of how those issues intersect. Earlier in the year, the Californian Senator faced accusations of rewriting history after she tried to characterise a 2008 San Francisco policy that reported undocumented youth to Immigration and Customs Enforcement when arrested by local police, regardless of whether or not a crime had been committed. Harris said handing over undocumented youth to federal authorities was “an unintended consequence” of the policy. Critics disagree.

Incidents like these have helped pigeonhole her as a relic of the “tough on crime” era of the 1990s and 2000s; a time that has been criticised, particularly by the insurgent progressive-left, as a regressive style of thinking that led to the unfair targeting of millions of African Americans.

During the campaign’s staged events, Harris has attempted to play to her strengths: utilising her time as a prosecutor to turn the to-and-fro of the debate stage into moments that cut through the morning after. However, voters this cycle appear less keen on intra-party warfare, punishing candidates—like former Secretary of Housing and Urban Development, Julian Castro—whose attacks look too aggressive. It is probably not a coincidence that the best-performing candidates (Biden, Warren) are those that have maintained a folksy, affable demeanour.

Harris has also been occasionally dishonest, sometimes egregiously so, in an attempt to burnish her progressive credentials. When talking about gender issues, Harris has continuously muddled equal pay with the gender pay gap. Whilst this may play well with less engaged voters who are concerned with gender inequity, it does no favours for her reputation among policy fanatics, a group of people who are almost certain to turn up on primary/caucus day.

Perhaps her biggest obstacle to the nomination is a nexus of problems that can be summarised as a lack of authenticity: supporting Bernie Sanders’s Medicare-For-All policy, until she didn’t; taking Biden to task for his position on busing during the second round of debates until she confirmed she took the same view only a few days later. Time and again, Harris tries to sound a radical note before retreating back to a moderate tune. These strategic blunders have meant that Harris is neither competing solely in the progressive lane (with Sanders and Warren) or the moderate one (with Biden and Klobuchar) but is attempting to have it both ways. As the saying goes: those who stand in the middle of the road tend to get run over.

Her dire performance in the horserace before a single vote has been cast could be fatal for Harris’s chances. She polls less well among the mainly white, mostly rural voters of Iowa, a state whose first-in-the-nation caucus is crucial for picking up much-needed momentum and acquiring the veneer of a viable candidate. YouGov had Harris at only 6 percent in Iowa at the end of August, a result that, if repeated next February across the state’s districts, could fail to land Harris a single delegate. A catastrophic result for a senior politician who was considered one of the most promising at the beginning of the year.

As the race consolidates into a top tier and everyone else, Harris has found herself on the wrong side of that line. Unless something dramatic happens, it is not a question of if Harris pulls out of the race, but when.