Recommended

Straw Men and Viewpoint Manicheanism

Each “side” sees the other’s behavior as evidence of evil, and their own behavior as justified on the ground that we good folks must defend ourselves against them.

The fallacy of special pleading—also known as the double standard—occurs when one offers a special excuse for one’s own violation of a standard that one continues to apply to others. At a buffet, one person says to another, “Let’s stock up before all the hoarders get here,” as if preemptive hoarding is different from hoarding. This move resembles the fundamental attribution error, which occurs when one attributes the negative behaviors of others to fundamental features of their character, while attributing one’s own negative behaviors to circumstantial factors.

When opposing parties adopt these attitudes toward one another’s views, a vicious cycle results: Each “side” sees the other’s behavior as evidence of evil, and their own behavior as justified on the ground that we good folks must defend ourselves against them. This suboptimal and highly contagious cognitive condition, which unfortunately characterizes much of our contemporary political landscape, is what I’ll call “Viewpoint Manicheanism.”

People on the collectivist Left often discount the evils historically associated with socialism, attributing them to totalitarianism or dictatorship, while attributing the evils historically associated with capitalism to its very nature, which they identify as the selfish profit motive. People on the libertarian Right, meanwhile, often dismiss the evils historically associated with capitalism, attributing them to corruption or government interference, while describing the historical evils associated with socialism as the inherent features of an evil ideology that tramples over individual rights.

Just as the sight of preemptive hoarding encourages others to hoard, the sight of special pleading by a group’s opponents encourages members of that group to avail themselves of the same tactic. Since they are employing a double standard, we have to, just to be on an even keel.

This tendency gets support from another cognitive bias for which we are hard-wired, which is to be more likely to notice anything negative, and to treat it as more salient, a tendency evolution fostered because being injured, attacked, or eaten matters much more to the transmission of genes than pleasant experiences do. These dispositions combined virtually guarantee a downward spiral into a sort of metastasized version of Viewpoint Manicheanism. The radicals on both ends of the political spectrum insist that ethics no longer apply to them, given the blatant, inexcusable evils of the other side.

After enough back and forth along these lines it seems to both sides that the other side is the one relying upon intellectual dishonesty. Nobody wants to lose face, and the exchange quickly degenerates to a clash of fallacies, sophistries, accusations of fallacies and sophistries, and eventually outright insults. It’s hard to remain neutral when one sees intellectual comrades and opponents duking it out. But, however understandable, such behavior only contributes to polarization.

Is it really plausible that half the country—the other half—has really become that evil, that stupid? No. A more likely explanation is that too many of us are falling for Viewpoint Manicheanism, a socio-cognitive pathology that inflames emotion, eclipses reason, and encourages demonization on both sides.

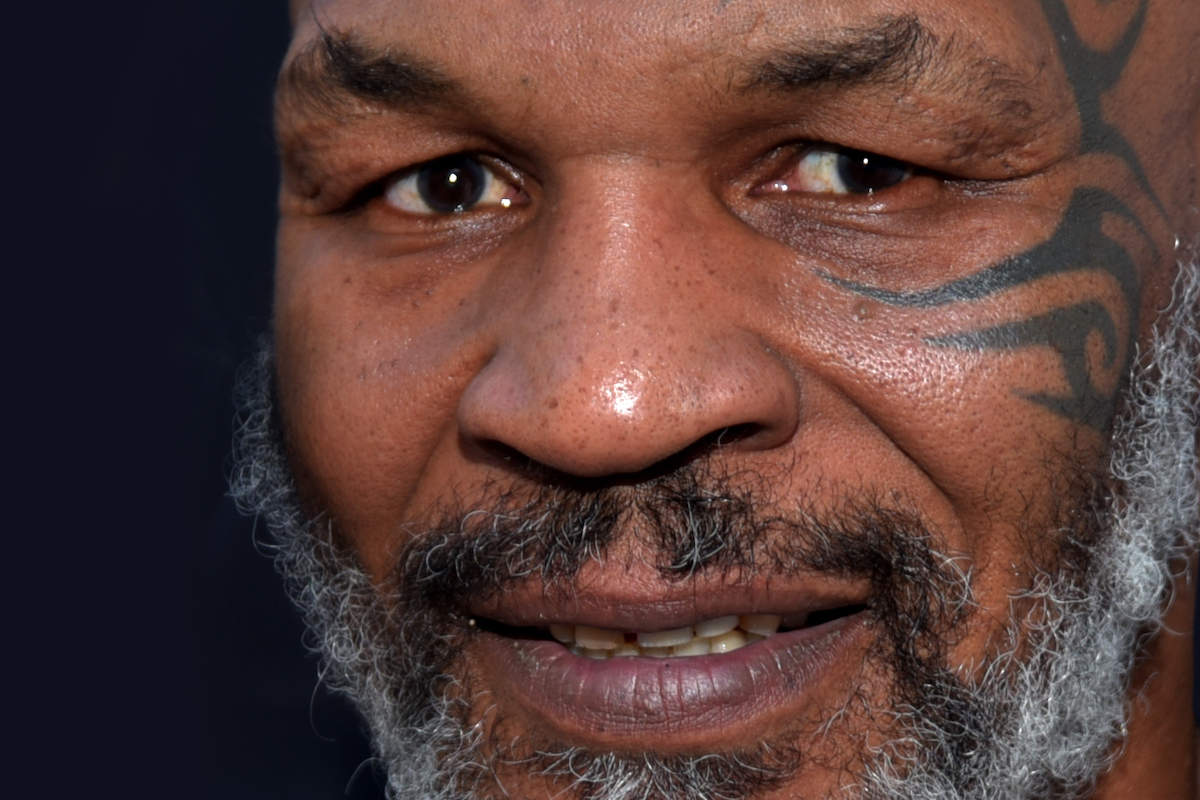

One possible strategy for inoculating oneself against this contagion is by discarding the straw man. A straw man is an expedient mischaracterization of an opponent’s position—it is not only logically fallacious, since a mischaracterization of X is irrelevant to the assessment of X, but it serves no good purpose. It annoys one’s opponent, encourages divisiveness and defensiveness, and threatens social cohesion. A straw man exposed also reflects poorly on its author, revealing either that they are not a good reasoner or that they are acting in bad faith. One can always come back and correct the mischaracterization, defeating it, in which case the straw man backfires on the person using it. That’s like beating up a poster of Mike Tyson, only to then have to invite the real Mike Tyson into the ring.

Conversely, the principle of charitable interpretation, or the steel man, requires us to be charitable when interpreting others’ views. A steel man not only honors the principle of charitable interpretation, but presents a stronger version of the interlocutor’s position, if not the strongest. Then, if there are objections, they are at least to a decent version of the opponent’s position. It also shows the opponent you fully understand what they consider good and right about their position. It is superior to the straw man, because if you then have a solid objection to the steel man, you’ve defeated the best version of the argument, like knocking out Tyson himself in the ring.

The point is not to win, though. It is to figure out which view makes the most sense, because, as a rational being, you (ought to) want to know whatever is most likely to be true. In a cooperative inquiry, uncovering the truth is the primary goal. There are competitive contexts, however, in which you ought not to help your opponent make their best case, such as when you and your opponent are in a zero-sum game, such as in a legal battle, or when competing for sales, votes, dates, and the like.

It is not clear whether we should view the political arena as zero-sum, given its competitive nature. But if we want to find the best moral reasons for accepting one political ideology over another, then we should view such inquiry as a cooperative, non-zero-sum game, in which finding the moral truth is the guiding value. We should therefore give our opponents the benefit of the doubt, and steel man their views. If someone mischaracterizes your view in such a context, instead of accusing them of sophistry, assume it was unintentional. Without proof of evil intent, accusations of evil intent only make matters worse, inviting the slippery slope to Viewpoint Manicheanism.

The difference between uttering a false statement one believes is true and uttering a statement one knows to be false is crucial; only the latter is lying. Likewise, the difference between engaging in faulty reasoning one thinks is rational, and using reasoning one knows is fallacious is crucial; only the latter is sophistry. Absent good evidence that someone is lying or engaging in bad faith, it is better to explain why one doubts the veracity of a statement or the validity of its reasoning.

If, however, all you care about is promoting the narrative of your political tribe, then you have already chosen to treat the matter as a zero-sum game; you’re likely already infected with Viewpoint Manicheanism. Consequently, honesty, truth, and fair debate are seen as naive in the grab for power, persuasion, and minds. All is fair in love and war. We’re the good guys, they’re the bad guys. The ends justify the means.

If you’re interested in furthering honest political inquiry, consider playing the steel man game: “Can we steel man each other’s view, to make sure we understand them?” This is part of another game one of my graduate school mentors encouraged us to play, the “belief game”: First try to completely understand the other person’s philosophy, occupy it from the inside, see the world through that philosopher’s eyes. Only then are you in a legitimate position to speak to its flaws, if any survive that exercise in cognitive empathy. Playing the steel man game is a smaller version of that larger endeavor.

I would encourage everyone to consider playing the belief game with the broadest political perspective of one’s opponents. For the individualists, for example, I’d recommend John Rawls’s A Theory of Justice, and for the collectivists Robert Nozick’s Anarchy State and Utopia, or any of Ayn Rand’s works. You might see some value in an opponent’s views. You might find you have more in common than you previously thought, something Viewpoint Manicheanism prevents.

So, next time you feel the desire to criticize an ideological opponent, consider whether you both might be willing to play the steel man game instead. “I’m curious. What’s your best argument for that view?” It’s not really risky, because if your opponent just keeps your steel men and their straw men, everyone will see your goodwill and their lack thereof, incentivizing a race to the top, rather than the bottom. It’s at least worth a try.