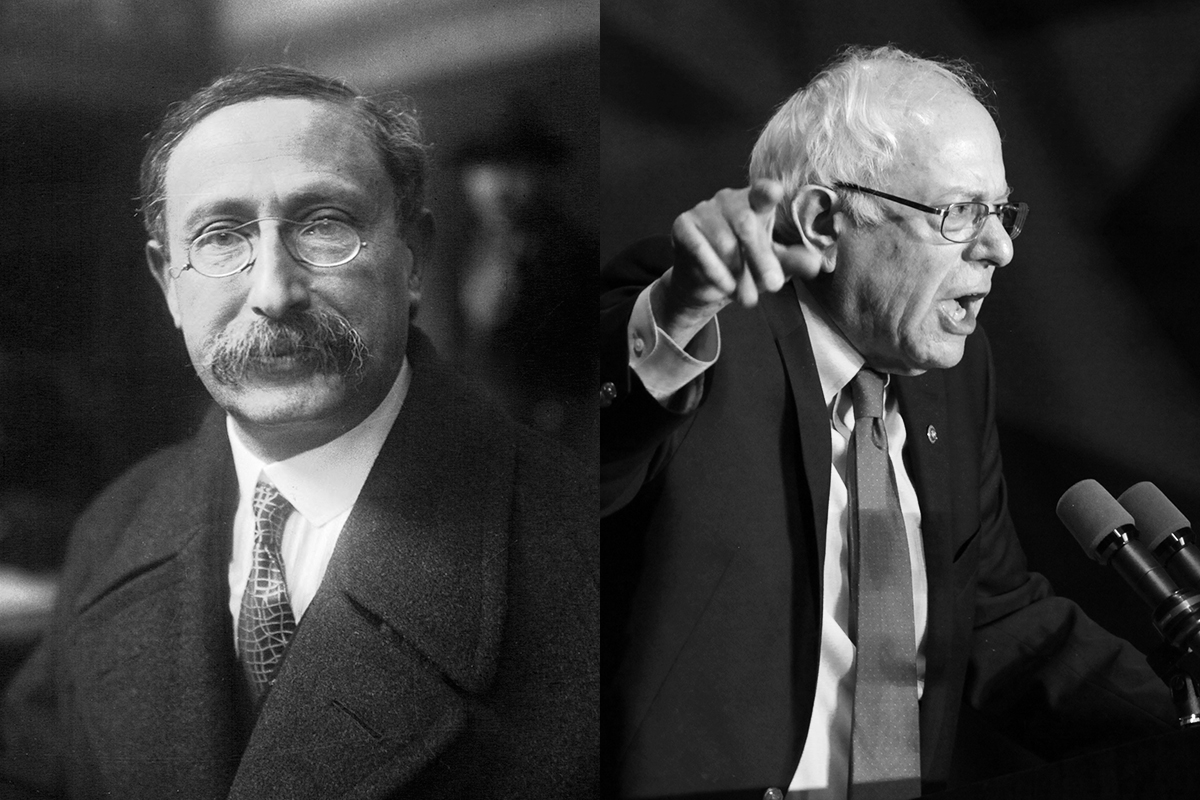

Whither Léon Blum?—Paul Berman's Misplaced Faith in Bernie Sanders

Jeremy Corbyn’s record of praising terrorist organizations and celebrating artwork that looks like it was commissioned by Joseph Goebbels to the long list of condemnations of Labour issued by Jewish organizations in the UK.

Just before the Second World War, the father of philosopher Emmanuel Levinas told him why it was necessary to make France their home: “A country capable of splitting itself in two over the honor of a little Jewish captain is a country where we have to go as soon as possible.” Levinas was a Lithuanian Jew who became a French citizen in 1939, after which he joined the military as a translator and ended up as a prisoner of war in Germany. Many of his family members died in the Holocaust, but he survived the war and returned to France where he lived the rest of his life.

The Dreyfus Affair divided France just a few decades before the Second World War, and Levinas’s father saw in the controversy the soul of a society that values truth and justice over the ancient hatreds and violent dogmas that were consuming so much of Europe. But the pardon and vindication of the “little Jewish captain” Alfred Dreyfus—who had been falsely accused of treason—was the result of a process that, as Levinas’s father observed, tore France in half. France was the country of Émile Zola, but it was also the country of Édouard Drumont and the howling mobs who read his antisemitic screeds and joined his campaigns against the country’s Jews.

Victor Klemperer, a philologist and diarist who remained in Germany for almost the entirety of the Second World War, once referred to the Jews as a “seismic people.” It’s an apt metaphor—the tremors of antisemitism are an unfailing sign that a society is in grave danger (which is why it’s so often present in totalitarian regimes and mass movements), but conspiratorial suspicion of Jews has a tendency to create sporadic rifts, cracks, and sometimes earthquakes in even the most tolerant and liberal societies. In a series of articles for Tablet late last year, the American author and critic Paul Berman provides a kind of Richter scale reading for three of these countries: France, Britain, and the United States, and asks if the recrudescent antisemitism on the European Left is a sign of what’s to come on the other side of the Atlantic.

Berman provides a brief history of the Labour Party’s antisemitism crisis—from Jeremy Corbyn’s record of praising terrorist organizations and celebrating artwork that looks like it was commissioned by Joseph Goebbels to the long list of condemnations of Labour issued by Jewish organizations in the UK. This crisis has only deepened in recent months, with a spate of resignations by Labour members of parliament, ever-increasing opposition from the Jewish community, and surging distrust of Labour among British Jews.

Berman also discusses the influence of “Corbyn’s counterpart” in France, Jean-Luc Mélenchon, whose Unsubmissive France Party has “ended up as anti-Zionism’s principal home on the French Left.” During the 2014 conflict between Israel and Hamas, Jewish businesses and synagogues were attacked and, Berman writes, “…a street full of marchers broke into a cry of ‘Death to the Jews!’ And ‘Jew: Shut up, France is not yours!,’ together with ‘Allahu Akbar!,’ and ‘Jihad! Jihad! Jihad!’” Instead of condemning the protesters and their violence, Mélenchon complained about their targets, whom he described as “aggressive communities that lecture the rest of the country.”

Surveying these ugly episodes from across the Atlantic, Berman wonders: “Will the same miserable battle that has torn apart large portions of the European Left spread to America, not just on a miniature scale (which has already happened), but full blast, with national consequences?”

This question was worth asking even before a furious row erupted over Rep. Ilhan Omar’s inflammatory comments about Jews and Israel earlier this year. As Berman points out, there is no shortage of “American campaigners, student councils, minor and major politicians, immigrant activists, distinguished intellectuals and vigorous chants” that demonstrate a renewed anti-Zionist energy in the country, and outright antisemitism is often lurking in the background. Sometimes, it is shameless enough to appear in the foreground: the organizers of the Women’s March (the largest protest in American history) openly and defiantly align themselves with Louis Farrakhan and yet manage to maintain their privileged positions on the activist Left.

Berman’s 2003 book, Terror and Liberalism, was one of the earliest warnings about the emergence of an increasingly assertive illiberal Left in the twenty-first century. But unlike, say, Nick Cohen’s polemic What’s Left? (published four years later), Terror and Liberalism is about more than the Left’s excesses and disfigurations. It is also a sweeping intellectual history of the twentieth century’s totalitarian mass movements—communism, fascism, and Islamism.

Berman argued that all of these movements were animated by the conviction that it’s possible to build societies free from liberalism’s contradictions and compromises. They were all permanently organized for war and infatuated with death and martyrdom. And they were all paranoid and conspiratorial, convinced that they were encircled by enemies and infiltrated by spies. These “subversive dwellers in Babylon,” Berman wrote, “were the bourgeoisie and the kulaks (for the Bolsheviks and Stalinists); or the Freemasons and cosmopolitans (for the Fascists and Phalangists); and, sooner or later, they were always the Jews …”

Today, Jews aren’t just scapegoated and despised by Islamists who march through the streets of Paris—they’re also regarded with suspicious contempt by people who, as Berman put it, are supposed to be the enemies of “antique bigotries and of modernized bigotries.” Berman argued that there is “pressure on the Western Left to accommodate, in the name of anti-racism and Third World solidarity, as many Islamist principles as possible, in regard to blasphemy, gender roles, and the iniquity of the Jews—a pressure on the Left, that is, to temper or creatively adapt various of its own historic fundamentals.”

In Terror and Liberalism, Berman reminded us that the Left had faced such pressures to accommodate totalitarianism and prejudice many times, and its failures were often spectacular. He recalled the “curious case of the French Socialists of the 1930s,” who “boasted of old and impeccable democratic credentials, reaching back into the nineteenth century.” In Prime Minister Léon Blum, they had also “managed to produce a great leader … who knew how to fuse French patriotism with the cause of social justice and the loftiest of cultural values.” Blum was the first Jew to serve as the prime minister of France, and he was a committed Zionist whose experience witnessing and reporting on the Dreyfus Affair made it the formative event of his political life. As such, his revulsion to Hitler and Nazism was visceral, and his resistance to the idea of accommodating (much less collaborating with) Germany was implacable.

However, as Berman explained: “… the French Socialists had their factions, and Blum and his supporters did not represent the entire party.” Another “somewhat larger faction” was led by Paul Faure, and this faction—although it was opposed to Hitler—was so terrified by the prospect of another war in Europe that it was willing to rationalize Nazi aggression and “make every effort, strain every muscle, to avoid a new Verdun.” The Paul-Fauristes argued that Germany had suffered under the Treaty of Versailles, and that Germans were being mistreated in Slavic countries. Therefore, shouldn’t proper socialists be concerned about the warmongers, arms manufacturers, and leaders of great powers “who stood to benefit in material ways from a new war”? Many French socialists began to wonder if “…on the Jewish question, just as on several other questions, Hitler was wrong, but perhaps not entirely wrong.” After all, Jewish financiers did appear to hold a lot of power. Many of those demanding confrontation with Hitler were Jews. The French prime minister—among the noisiest of those the Paul-Fauristes called warmongers—was a Jew. Hitler’s antisemitism was ugly, vulgar, and atavistic, but didn’t it also explain the opposition of his Jewish enemies to appeasement?

After the invasion of France in June 1940, Léon Blum and his allies refused to cooperate with Philippe Pétain’s Vichy government, while the “majority of the Socialists in the National Assembly, the anti-war faction, voted with Pétain.” The country that had so inspired Emmanuel Levinas’s father had become a Nazi outpost. Blum was sent to Buchenwald, where he was held for two years before being transferred to Dachau. He later wrote: “I was in the hands of Nazis. For them I represented something more than a French politician. I also embodied what they hated most in the world, since I was a democratic socialist and a Jew.” Even as his allies on the French Left abandoned him to the Nazis, Blum’s political convictions didn’t waver. Nor did he creatively adapt his principles—on the contrary, he affirmed them, even in the face of Nazi occupation.

It’s not hard to imagine what Blum would say about the state of the contemporary European Left—from Corbyn’s obsequious praise for antisemites to Mélenchon’s refusal to confront them. A man who had the courage to defy the Nazis and embrace his Jewishness in the shadow of Buchenwald would not have much patience for a man who couldn’t summon the political courage to condemn rioters chanting “Death to the Jews!” in the streets of Paris. Nor would he be impressed by a Labour leader who compares antisemitic propaganda to the work of Diego Rivera.

But what about America? Yes, comments abut Jews and Israel by politicians like Ilhan Omar and Rashida Tlaib, the apologies for Islamist antisemitism and obsessive anti-Zionism in many quarters of the media and on American campuses, the influence of sulfurous antisemites like Farrakhan, and the elevation of demagogues like Linda Sarsour and Tamika Mallory to the status of cultural icons are all disturbing realities. But do they mean that the Corbynization of the American Left is inevitable? Or, as Berman asks, “Is America, in short, different?”

Berman’s answer is that America is indeed different. And the American political figure who he says demonstrates this difference is, confusingly, Bernie Sanders. Berman begins by criticizing Sanders for adopting the “foreign policy default position” of the American Left in 2016 (a mixture of apathy and reflexive castigation of the United States)—that is, when he wasn’t assiduously avoiding foreign policy altogether. But this was before Sanders started delivering foreign policy speeches that, to Berman’s ear, seem to capture the values that many leaders of the European Left have abandoned: democratic solidarity, internationalism, and anti-authoritarianism.

Berman was particularly impressed when, having condemned Trump for his failure to mention Russia’s 2016 election interference at the UN, Sanders called for solidarity with “supporters of democracy around the globe, including in Russia” (this was during his first major foreign policy speech in September 2017). In Sanders’s second foreign policy speech a year later, he built upon this theme of democratic solidarity, identifying a “new authoritarian axis” in the U.S. and Europe and arguing that “we need to counter oligarchic authoritarianism with a strong global progressive movement that speaks to the needs of working people…” Berman believes that, unlike Hillary Clinton, Sanders has an “ability to point to things that are larger than a laundry list, and grander than strength and safety. The worldwide struggle for democracy and justice is his cause, and solidarity is his principle.”

But the evidence that Sanders’s foreign policy would revive the best traditions of the social-democratic Left—those of internationalism and anti-totalitarianism—is thin. His comments about the “new authoritarian axis” could have been uttered by any Democratic candidate in the age of Trump, Fidesz, Law and Justice, and so on. What Berman describes as Sanders’s “salute to the internationalist and anti-totalitarian arguments of Winston Churchill” is practically obligatory for any American politician speaking in Fulton, Missouri, where Churchill delivered his “Iron Curtain” speech in 1946. Until Sanders gives us some idea of what he might actually do to win the “worldwide struggle for democracy,” we shouldn’t get too excited.

Berman understands all of this. When he wonders if any left-wing American politician will “revive a few of the instincts of the 1940s social-democratic Left, updated and corrected for our own entirely different era,” he quickly admits: “I have allowed my thoughts to wander out of the zone of the realistic.” Still, for some reason, he finds hope in Sanders’s vague appeals to the Left’s higher principles. And for some even more obscure reason, he believes Sanders to be the figure who demonstrates that “obsessive anti-Zionism” won’t take hold on the mainstream American Left.

Although Berman admits that Jews and Israel were largely missing from the foreign policy speeches in 2017 and 2018, he says Sanders has “instinctive sympathy” for the Zionist project. During a town hall meeting in Vermont in 2012, Sanders argued that Israel had a right to defend itself from indiscriminate rocket attacks and shouted “Shut up!” at constituents who loudly claimed otherwise, which “suggested that his sympathy for certain kinds of anti-Israel outrage has its limits.” Berman also points out that Sanders repeatedly has to admit that he’s “been a little hasty in expressing a sympathy for this or that Palestinian protest.” Among Sanders’s counterparts in Britain and France, Berman concludes, “there is a chilly spot for the Jews and the Jewish state—icy, in Corbyn’s case. But in the American enemy of oligarchical authoritarianism there is a warm spot.”

Is there? Berman spends most of his article about Sanders outlining all the ways in which the “American enemy of oligarchical authoritarianism” has aligned himself with the obsessive anti-Zionists, about whom Berman is most concerned. Perhaps it is true that Sanders “relishes the memory of his student socialist idyll in 1963, toiling for the brotherhood of man as a guest of Hashomer Hatzair at the kibbutz Sha’ar Ha’amakim, near Haifa.” But why did he ask Linda Sarsour—who thinks “nothing is creepier than Zionism,” and who is an unapologetic ally and defender of the Nation of Islam—to introduce him at his rallies? Why did Sanders “help to define as admirably progressive” (in Berman’s own words) Rashida Tlaib, who “turns out to be a champion of Israel’s demise”? And why did Sanders tell the New York Daily News editorial board that his “recollection is over 10,000 innocent people were killed in Gaza” during the 2014 war, a statement that betrayed his readiness to believe outlandish reports of Israeli brutality?

A few months after Berman wrote his series for Tablet, a 2012 tweet by Rep. Ilhan Omar resurfaced in which she had claimed that “Israel has hypnotized the world.” She later claimed that support for Israel is “all about the Benjamins,” and lamented the “political influence in this country that says it is okay for people to push for allegiance to a foreign country.”

As the House debated a resolution to condemn antisemitism in response to these remarks, Sanders issued a statement in support of Omar: “What I fear is going on in the House now is an effort to target Congresswoman Omar as a way of stifling that debate [over the Israeli government’s behavior]. That’s wrong.” Sanders’s statement attacked a straw man—almost nobody was arguing that legitimate criticism of Israel should be silenced. But Sanders knew he would face furious opposition from progressives if he condemned Omar, so he refused to do so. The most Sanders will say about Omar is that she “has got to do maybe a better job in speaking to the Jewish community”—this sounds like a polite request for greater tact rather than a principled stand against bigotry.

It doesn’t matter if Sanders still harbors nostalgia for the radical socialist Israeli experiment of yore—he is notably less enthusiastic about the liberal capitalist nation it has become. Nor does it matter if he does indeed retain a warm spot in his heart for Jews—he has repeatedly demonstrated that political expediency can cool it off. This is why, if Sanders is the best defense against the Corbynization on the American Left, we’re in trouble. While antisemitism hasn’t become institutionalized on the American Left as it has in the Labour Party, in a way, this makes Sanders’s vacillations and excuses all the more feeble. If he can’t summon the political courage to fight against the prejudices and pathologies that have infected Europe when it’s relatively easy to do so, what are the chances he’ll manage if and when it becomes difficult?

In his 2015 biography Léon Blum: Prime Minister, Socialist, Zionist, Pierre Birnbaum writes that Blum was “certain of his rights and his legitimacy and unafraid of reprisals, refrained from protesting his arrest or requesting special treatment. He courageously defended his actions as prime minister as well as his Jewish identity, which he never tried to hide.” To the extent that the Left’s historic fundamentals are in opposition to totalitarianism, racism, and violent paranoia, Blum—like the Dreyfusards, whose tradition he upheld—embodied them. Sanders’s craven appeasement of anti-Zionists, on the other hand, is precisely what Berman decries: a corruption of those fundamentals “in the name of anti-racism and Third World solidarity.”

It is true that Bernie Sanders is no Jeremy Corbyn. In our current climate, perhaps clearing that exceedingly low bar is something to celebrate. But watching Paul Berman scratch around for evidence of Zionist fellow-feeling in Sanders’s meagre record is dispiriting, nonetheless. Amid his own anxious caveats, Berman yearns to uncover what remains of Blum’s heroic legacy in contemporary democratic socialism. It is a sad commentary on the state of today’s Left that one of its most incisive chroniclers must now listen so carefully for the faintest echoes of principles once trumpeted with such clarity.