Activism

A Black Eye for the Columbia Journalism Review

Essays attacking the left- or right-wing bias of this or that media outlet are, of course, old hat in my business.

Ideological polarization has become a growing problem in many sectors of society. But it is especially corrosive to public discourse when it infects organizations whose traditional role has been to hold everyone else to account for the integrity of their reporting. We need those organizations to act as a sort of referee when journalists of any description—including those at Quillette—fail to exhibit high standards. This becomes impossible when they instead act as combatants in the culture wars.

Earlier this month, for example, the Canadian Association of Journalists (CAJ), which describes itself as “the national voice of Canadian journalists,” “committed to protecting the public’s right to know,” and “dedicated to promoting excellence in journalism,” signed on to the claim that Canada is perpetuating an ongoing “genocide” against Indigenous people, and encouraged journalists to take on an activist role by promoting “decolonizing approaches to their work [and] publications in order to educate all Canadians about Indigenous women, girls & 2SLGBTQQIA people.” It hardly needs pointing out that this sort of explicit activist agenda—however well-intentioned—is completely incompatible with the project of objective journalism.

Meanwhile, the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC) now is apparently in the business of deplatforming mainstream pundits such as Christina Hoff Sommers. And an insider account of SPLC operations recently published in The New Yorker explains how the group has a built-in incentive to inflate the scope of “hate and bigotry” its researchers discover. “Though the center claimed to be effective in fighting extremism, ‘hate’ always continued to be on the rise, more dangerous than ever, with each year’s report on hate groups,” Bob Moser writes of his tenure at the organization. “‘The SPLC—making hate pay,’ we’d say.”

In recent years, this trend has come to infect the Columbia Journalism Review, which presents itself as “the intellectual leader in the rapidly changing world of journalism.” In the past, this self-branding was credible. And the CJR still publishes plenty of valuable articles about the world of journalism (such as this interesting survey of publicists’ opinions of journalists, by Andrew McCormick). But in some cases, the CJR has succumbed to the above-described trend, by which watchdog organizations that once prized themselves on fastidious neutrality now lend their voice to fashionable ideological postures.

Last month, the CJR published an article by trans activist Parker Molloy essentially demanding that when it comes to the issue of male-bodied individuals seeking to compete in female athletics, journalists should present only one side of the issue—on the basis that naysayers don’t “have all the facts,” and their words “could be used to reinforce ignorance.” These are thinly coded appeals to de facto self-censorship, and it is strange to see them published by an outlet whose nominal purpose is to promote excellence in journalism.

This month, CJR stepped over the line again. And this time, the resultant hit on the CJR brand was worse. Molloy’s piece was torqued and one-sided. But it did not contain any actual errors. The same was not true of Jared Holt’s June 12 CJR piece, entitled Right-wing publications launder an anti-journalist smear campaign, which attacks a study by researcher Eoin Lenihan that shows a close ideological connection between Antifa and the journalists who follow Antifa most closely on Twitter.

As a Quillette editor, I initially was interested to see what Holt had come up with, since he often has performed valuable work as an investigator with the progressive advocacy group People For the American Way, and because Quillette is featured as one of the “right-wing publications” that allegedly served to “launder” Lenihan’s work.

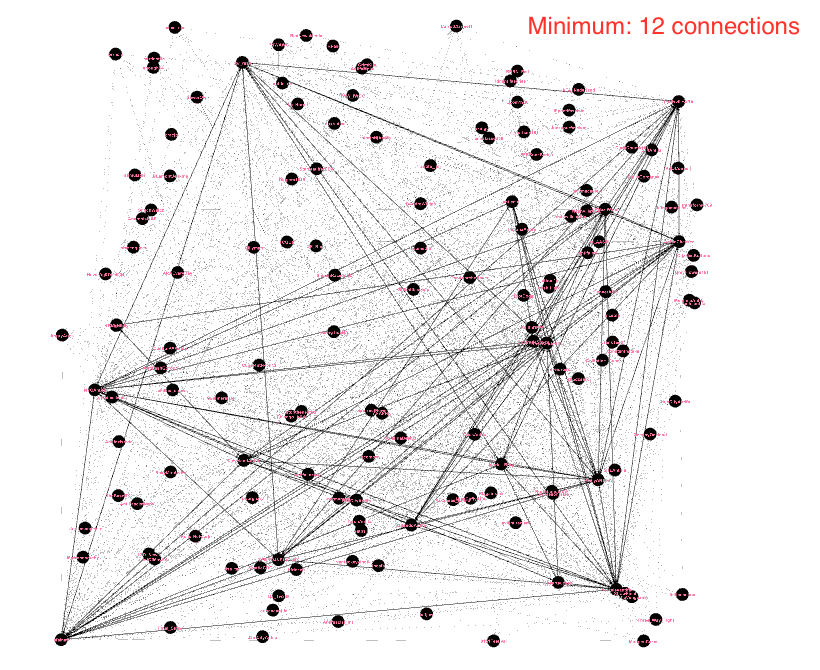

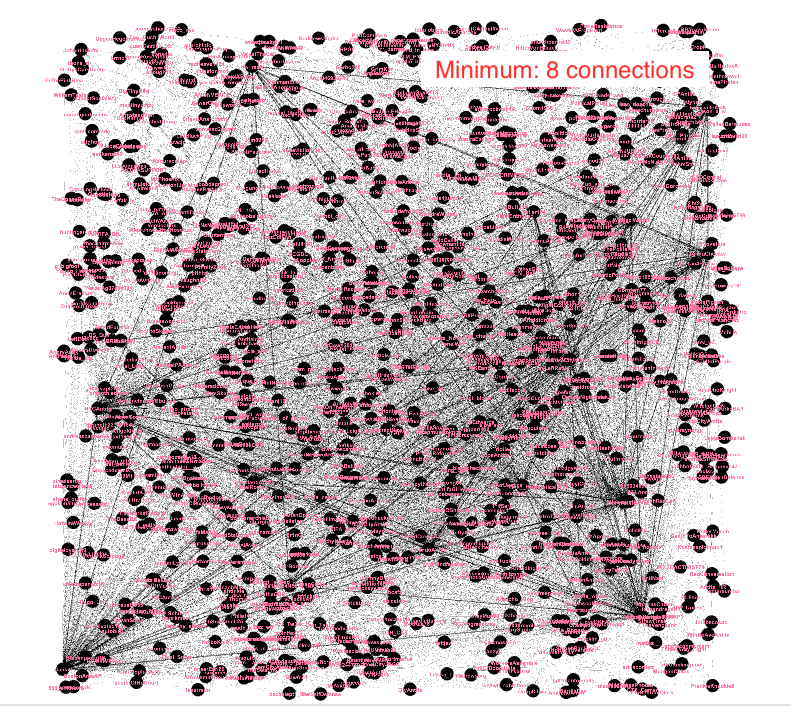

But, to quote a headline from last week, Holt’s article “backfired.” As two detailed critiques have shown, the CJR article contains important mistakes and intellectually dishonest reporting. Worst of all, Holt doesn’t appear to understand Lenihan’s methodology. His CJR article suggests that a journalist was deemed “highly connected” to Antifa under Lenihan’s analysis if that journalist had eight or more connections on Twitter to “either accounts run by antifascist activists, or [run by] one lecturer at Hong Kong University.” There are two separate mistakes here. To meet Lenihan’s criteria, a journalist wasn’t required to have eight or more connections to any ‘antifascist’ account (a standard that would have swept up untold thousands of accounts). Rather, Lenihan’s requirement was that such journalists must be connected to eight or more entries from within a prescribed set of just 16 influential Antifa accounts—a much stricter criterion that was met by only 15 well-known journalists. Moreover, as even CJR has admitted by way of correction (which the editors euphemistically have termed an “update”), Holt misidentified the author who wrote Antifa’s foundational text—Mark Bray—confusing him with another scholar of the same name who works in a completely different field, in Hong Kong.

Notwithstanding the dramatic CJR headline, Holt didn’t even pretend to identify any real errors in Lenihan’s analysis. The closest he comes in this regard is casting doubt on Lenihan’s characterization of Alexander Reid Ross as an “eco-extremist,” and complaining about Lenihan’s description of Emily Gorcenski as running a “Doxing site.” But Ross was an editor of the Earth First! journal, which advocates for “direct action” and sits at the radical editorial extreme of the environmentalist movement. And Gorcenski has bragged openly about her doxxing. (As for Holt’s suggestion that Lenihan is wrong to say that Antifa is often “more violent” than fascist groups, we’d suggest that Holt pay attention to recent events in Portland and Washington.)

For the most part, Holt falls back on the sort of name-calling (“right-wing troll” and “far-right social media user” both make appearances) more commonly associated with comment threads and Twitter fights. Much of Holt’s article is padded out with speculation about how unhinged extremists might exploit Lenihan’s article to nefarious ends, as well as a character-assassination subplot about Lenihan being suspended from Twitter following his use of a parody account that mocked political correctness. Just a few years ago, this sort of snobbish ad hominem approach to journalism would have itself been the subject of CJR critique. In 2019, the CJR serves it up as featured content.

But there was one thing that Holt got right: Neither Lenihan nor Quillette nor any other media outlet acquiesced to Holt’s demand to inspect their fact-checking methods. Moreover, Lenihan himself was reluctant to divulge the details of his research methods with Holt because he intends to adapt this project for publication in an academic journal. Some journals will disqualify a submission if the contents already have been shared publicly (though, contrary to Lenihan’s own expressed concerns, this is not the case with Social Networks, a publication to which Lenihan already has submitted his work).

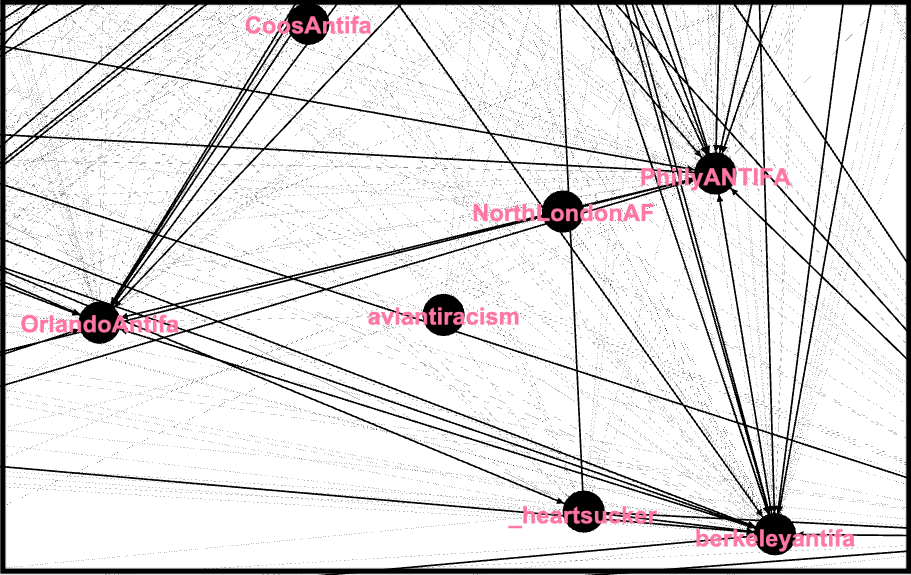

But Lenihan did share his data with Quillette—including a draft of the academic article he’s written about his research, a list of the 16 Antifa seed Twitter accounts he used as the basis of his analysis, the identity of the 58,254 users who were found to follow one or more of these accounts, the scripts Lenihan used to analyze and record relationships among Twitter accounts, the tabulated statistical results of this analysis, and the list of 75 text strings used as proxies to distinguish truly extreme Antifa-related beliefs (“dox them,” “punch them,” “club them,” etc.) from the more moderate campus-friendly version (“fuck white people,” #fuckwhitesupremacy, #goodnightwhitepride, etc.). And on Tuesday, Lenihan authorized me to discuss this material publicly. All of this data was provided in digital format. So not only was I able to fact-check the integrity of Lenihan’s own data-visualization figures, I also was able to create my own variations, and so could test the effect of different parameters so as to help ensure that the author wasn’t cherry-picking his values in a way that allowed him to achieve pre-determined results. In the figures I prepared below using Gephi’s Degree Range tool, for instance, I show how the structure of Lenihan’s mapping of Twitter relationships would change when different values are applied in regard to a user’s minimum required connections to the seed list of 16 Antifa accounts.

As is well known to anyone who uses data-visualization software (or watches TED Talks), there are all sorts of exotic ways that large data sets may be presented. And Holt goes on at some length in his article about how splashy quantitative methods can bewilder ordinary readers and lay journalists. But Lenihan’s analysis is actually fairly straightforward, and all of his raw data is drawn from a publicly accessible source. Similar forms of analysis have been used for years by other scholars to track relationships among right-wing extremists (without provoking any kind of controversy). These methods also are commonly used by marketers seeking to identify key influencers and relationships within their target demographics. (There are more advanced methods available that incorporate machine-learning algorithms, but Lenihan doesn’t employ them.)

Lenihan’s conclusion that the high-profile journalists who monitor Antifa most closely on Twitter also are the ones who most dependably write pro-Antifa articles is referred to by Holt as an “allegation”—as if this were some kind of criminal indictment. But it’s not clear why Lenihan’s findings strike Holt (or anyone) as particularly controversial—since the journalists whom Lenihan identifies by name don’t exactly hide their pro-Antifa views. Jason Wilson of the Guardian, most notably, writes fawningly of Antifa activists—and even appears to have endorsed the Antifa tactic of doxxing its enemies, a tactic Lenihan himself (rightly) abhors.

Indeed, the very idea that Lenihan was engaged in any kind of “smear campaign” (to quote the headline on the CJR article) is a fiction that dissolves upon contact with Lenihan’s own words. “It should be stressed that a journalist’s close social-media engagement with any particular group should not be seen as incriminating per se,” Lenihan wrote in Quillette. “Many journalists follow—and even interact with—all manner of figures online, either out of personal curiosity, professional interest, or even as a means of developing sources. In identifying this group of 15 journalists whose engagement with Antifa is especially intense, our goal was not to accuse them of bias out of hand, but rather to identify them for further study, so as to determine if there was any overall correlation between the level of their online engagement with Antifa and the manner by which these journalists treated Antifa in their published journalism.”

In other words, the analysis that Holt characterizes as some kind of dangerous plot against progressive journalists is basically just a study of media bias—the sort of subject that, until recently, CJR was known for covering dispassionately.

When it comes to statistical studies, bigger data sets typically deliver more robust results. And in this respect, Twitter supplies researchers with a gold mine, since the relationships among users generally are public, and this information easily can be harvested en masse by automated data-gathering tools. Lenihan’s methods are being used by many other researchers to investigate all manner of trends in every sector of our society, including journalism. An outlet such as CJR should be encouraging the use of modern analytical techniques, rather than presenting them as sinister and opaque.

Essays attacking the left- or right-wing bias of this or that media outlet are, of course, old hat in my business. But CJR is a special case. It is a respected and venerable institution. We need outlets such as CJR—and, yes, the CAJ and SPLC—to act as voices of authority when writers, editors and broadcasters go astray. One hopes that this cautionary tale, and others like it, help lead them back to their original mission.