Books

On Its 70th Anniversary, Nineteen Eighty-Four Still Feels Important and Inspiring

Nineteen-Eighty Four, whose first publication took place 70 years ago today, is itself a sort of anti-novel, one that undermines its own dramatic tension in a way that might now be described as postmodern.

Nineteen Eighty-Four is divided into three parts, the second of which is structured around Winston Smith’s love affair with Julia, a co-worker at the Ministry of Truth. Their romance begins with Smith offering Julia the sort of smooth talk that would send any woman’s heart aflutter: “I’m thirty-nine years old. I’ve got a wife that I can’t get rid of. I’ve got varicose veins. I’ve got five false teeth.”

Moments later, he seals the deal by telling Julia that she’d always been in his thoughts. “I hated the first sight of you,” he tells her. “I wanted to rape you and then murder you afterwards. Two weeks ago, I thought seriously of smashing your head in with a cobblestone.” Naturally, Julia is seduced. Several pages later, Winston “pressed her down upon the grass, among the fallen bluebells.” It is a symptom of George Orwell’s genius that, taken in context, this sequence makes perfect sense.

In his life, Orwell seems to have been somewhat mortified by the sex act. And one can almost see him squirming slightly as he wrote this scene out during the late 1940s, when he was holed up on the Scottish island of Jura, already suffering from the lung disease that would kill him shortly after the book’s publication. Yet prig that he was, Orwell understood the human sex instinct quite well. He knew that the fantasies we act out among the bluebells often emerge from life’s jealousies and agonies. For Smith and Julia, sex is an escape from the loneliness they suffer in a world of lies. So even the most grotesque truths serve as aphrodisiacs.

“You like doing this? I don’t mean simply me: I mean the thing itself?” asks Winston.

“I adore it,” answers Julia.

“This was above all what he wanted to hear. Not merely the love of one person but the animal instinct, the simple undifferentiated desire: that was the force that would tear the Party to pieces…Their embrace had been a battle, the climax a victory. It was a blow struck against the Party. It was a political act.”

The mechanics of their lovemaking—Winston doesn’t get things right on the first try, though Julia shows herself a model of patience—betrays something fundamental about Nineteen-Eighty Four: Winton Smith (whom I will always picture as John Hurt in the 35-year-old film adaptation) isn’t a hero, but an anti-hero, corrupted morally as much as physically by the diseased world around him. After an air raid in a prole neighbourhood, he kicks a human hand into the gutter as if it were a football. He succumbs to the Two-Minute Hate, enthusiastically doctors the past on behalf of a totalitarian regime he despises, and daydreams casually about rape and murder. Much of the book consists of Winston’s own selfish and even childish reveries. In fact, the stark confessional style of these passages is one of the aspects of Nineteen Eighty-Four I found compelling when I first read it as a child. Never before, and never since, had I read any author who’d read back to me my own petty internal narrative so perfectly.

Nineteen-Eighty Four, whose first publication took place 70 years ago today, is itself a sort of anti-novel, one that undermines its own dramatic tension in a way that might now be described as postmodern. At every juncture, Winston reminds us that his story will have no happy ending, that all will end in anguish and betrayal. Even O’Brien—the party enforcer and spy who would seem to have every reason to fill Winston’s head with false hope—tells him: “You will work for a while, you will be caught, you will confess, and then you will die…There is no possibility that any perceptible change will happen within our own lifetime. We are the dead. Our only true life is in the future. We shall take part in it as handfuls of dust and splinters and bone.”

Long before most, Orwell realized that totalitarian cults all tend to co-opt the idea of a Christian heaven that stands in glittering, celestial contrast to the grubby lives of those who labour to open its gates. But behind the real gates are Snowball’s glue factory. And among the torture racks of Room 101, one finds something worse. “Everybody always confesses. You can’t help it. They torture you,” says Julia. Even in the throes of first love, neither she nor Smith delude themselves on this point. But it would be wrong to call the book’s ending genuinely sad or tragic—since tragedy can’t exist in the absence of an individual, heroic spirit that, under Big Brother, is completely extinguished.

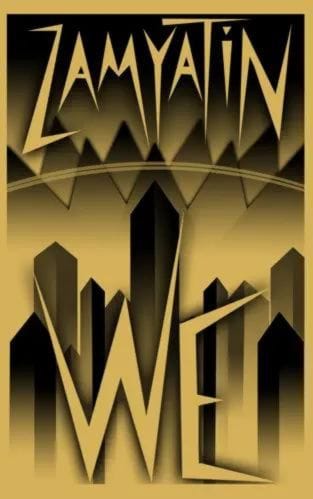

One might conceive an alternative version of Nineteen Eighty-Four in which Smith emerges heroic, true love prevails, and Orwell’s dark, moody atmospherics are replaced with the primary colours of an action adventure. But we don’t have to use our imagination, because that novel, titled We, already exists, having been written a century ago by Russian satirist Yevgeny Zamyatin. In fact, the plots of the two books are so similar that Zamyatin might have called out Orwell for plagiarism if he hadn’t died before Nineteen Eighty-Four was published.

Unlike Zamyatin, who’d made a career in science fiction, Orwell never had demonstrated much interest in technology for technology’s sake. And I doubt that he would have been able to construct the technical elements of the Nineteen-Eighty Four world without relying on Zamyatin’s pulp fiction. In this regard, we all owe a great debt to a Russian literature professor named Gleb Struve (1898-1985), who introduced Orwell to We long after Zamyatin’s death. In a thank-you note to Struve, dated February 7, 1944, Orwell wrote: “I know very little about Russian literature and I hope your book will fill up some of the many gaps in my knowledge. It has already roused my interest in Zamyatin’s We, which I had not heard of before. I am interested in that kind of book, and even keep making notes for one myself that may get written sooner or later.” (He also adds that “I am writing a little squib which might amuse you when it comes out, but it is so not OK politically that I don’t feel certain in advance that anyone will publish it.” That “squib” was Animal Farm.)

In We, the protagonist is D-503, who, like everyone else, lives in a glass apartment building that is constantly spied upon by the Bureau of Guardians (thought police). In time, he is seduced by I-330 (Julia), who takes him to the Ancient House (Mr. Charrington’s store) and introduces him to the secretive Mephi (The Brotherhood). True to Zamyatin’s sci-fi roots, his D-503 is a scientist tasked with building a spaceship so that the One State (the Party) can conquer other planets. Having no interest in rockets and ray guns, Orwell instead put his own protagonist at the heart of the MiniTrue propaganda apparatus, which allowed him to draw (loosely) on his experience as a wartime propagandist at the BBC.

The first edition of We appeared in 1924—a quarter century before Nineteen Eighty-Four. And the technological changes that took place between the publication of the two books are evident in their plot details. Radio became a mass medium in the 1920s. Television as we know it was invented in the 1930s. World War II ushered in widespread adoption of wireless communication technologies. (When the war began, non-German tank crews typically would communicate with flags—a practice that had become completely obsolete by the time the war ended.) And so Orwell replaced Zamyatin’s glass architecture (which itself can be traced to Jeremy Bentham’s 18th-century Panopticon penitentiary concept) with the Telescreen, an electric device that both broadcasts and records sound and video. In light of today’s proliferation of CCTV cameras, facial-recognition software and other surveillance technologies, Orwell seems extraordinarily prescient.

Nineteen Eighty-Four was written to warn readers about the intelligentsia’s weakness for totalitarian doctrines (especially communism), not as a set of real predictions about what the world of the future would look like. Nevertheless, it’s still impressive to see how many details Orwell got right. One thing he didn’t see coming, however, was the emergence of the internet in general, and social-media technology more specifically—which (for now) permits citizens to self-organize outside the direct observation of authorities. In the world of Nineteen Eighty-Four, “rebellion meant a look in the eyes, an inflexion of the voice; at the most an occasional whispered word”—because the Party monopolizes mass communication, all of which must pass through the Ministry of Truth. The internet, by contrast, allows dissidents to self-organize on a massive scale without using any one centralized node.

And yet even on this score, the warnings of Nineteen Eighty-Four have been vindicated by human nature, which hasn’t changed a bit over the last 70 years. Orwell knew that most of us—and even more so, our children—require little encouragement to rat one another out if we perceive some moral or ideological lapse.

One of the most important minor characters in Nineteen Eighty-Four is Parsons, an unflappably dumb and jingoistic Party apparatchik who lives in the same building with his phlegmatic wife and terrifying children, of whom he is immensely proud. “Mischievous little beggars they are, both of them, but talk about keenness!” Parsons tells Smith over lunch. “All they think about is the Spies, and the war, of course. D’you know what that little girl of mine did last Saturday, when her troop was on a hike out Berkhamsted way? She got two other girls to go with her, slipped off from the hike, and spent the whole afternoon following a strange man. They kept on his tail for two hours, right through the woods, and then, when they got into Amersham, handed him over to the patrols.” If a living Orwell were shown the vicious mobbing campaigns that pop up every day on Twitter and Facebook (with no explicit state encouragement whatsoever), he’d find this crowdsourced totalitarian spirit completely familiar, even if the underlying technology seemed alien.

Orwell also would be somewhat mystified by the type of subjects that now attract the most aggressive forms of thought and speech control. In that 1944 letter to Struve in which he confessed that Animal Farm was “not OK politically,” Orwell was alluding to his satirical treatment of Marxist orthodoxies, which, in various forms, constituted the woke dogma of his era. But in 2019, you can say anything you like about capitalism and communism, for the real locus of social panic among anti-liberal revolutionaries now is skin colour, sexuality and gender identity. The whole point of (pre-Stalinist) communism was to erase ethnic and even national distinctions by subsuming all of mankind into one vast egalitarian brotherhood—the complete ideological opposite of today’s progressive obsession with skin tone, customized pronouns and cultural appropriation.

I also think Orwell would have found today’s left to be absurdly delicate. Orwell was a socialist who cared about the real material conditions of the working class. His reporting took him from the slums of Europe to the depths of Britain’s coal mines. He risked his life fighting fascism in the Spanish Civil War, and got shot in the throat. In that age, this is simply what it meant to be a committed leftist. And it is amusing to think how he would respond if told that his opinions amounted to “violence,” or that Winston Smith’s rape fantasies made readers feel “unsafe.”

The first editions of Orwell’s books were published between 1933 and 1949, a period during which the antique class divisions of English society were under assault from mass-retail capitalism and total war. In his writing, he lampooned the intensely class-conscious Anglo-Indian world into which he’d been born, and exhibited a keen eye for the inane rituals required to sustain class hierarchies. In one of the untitled “As I Please” columns Orwell wrote for The Tribune, he wrote of his lodgings at Portobello Road, which he described as then being “hardly a fashionable quarter”:

The landlady had been lady’s maid to some woman of title and had a good opinion of herself. One day something went wrong with the front door and [we] were all locked out of the house…It was evident that we should have to get in by an upper window, and as there was a jobbing builder next door, I suggested borrowing a ladder from him. My landlady looked somewhat uncomfortable. “I wouldn’t like to do that,” she said finally. “You see, we don’t know him. We’ve been here fourteen years, and we’ve always taken care not to know the people on either side of us. It wouldn’t do, not in a neighbourhood like this. If you once begin talking to them, they get familiar, you see.” So we had to borrow a ladder from a relative of her husband’s, and carry it nearly a mile with great labour and discomfort.

Some leftist intellectuals of Orwell’s time made a show of adopting proletarian language, dress and customs, and lionized the working class as capitalism’s beaten down martyrs who would one day rise up to redeem their societies. The most vocal elements of modern leftist movements, by contrast, betray an attitude of complete contempt for working-class ideas and values, since poor people often vote for the “wrong” politicians, and freely flout the social-media-enforced taboos. A modern leftist wouldn’t avoid the “jobbing builder” next door because he was poor, but because he had a Trump bumper sticker on his F-150.

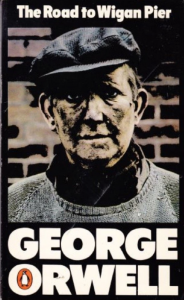

And yet, it’s also possible that Orwell might find these modern progressive attitudes to be no more hypocritical than those he observed in his own age. In his book Road to Wigan Pier, Orwell described how uninterested real working-class people were in the esoteric Marxist gibberish that formed the basis of daily debate among leftist intellectuals. One of the great challenges faced by socialists, Orwell realized, is that the intellectuals who want to lead socialist movements are fundamentally ignorant, and even contemptuous, of working-class attitudes.

In Nineteen Eighty-Four, the people of Oceania are divided between Party members (“knowledge workers” as we would now call them), who comprise about 15 percent of the society and are rigidly bound in every aspect of their lives; and the “proles,” who account for the other 85 percent, and who are allowed to do whatever they please so long as it doesn’t threaten state security. In Marxist mythology, capitalists use vicious schemes to keep the working classes oppressed. But in Orwell’s fictional world, all that’s required to keep the masses quiescent is a steady stream of pornography, gory movies and military propaganda.

One of my favourite scenes in Nineteen Eighty-Four—which I find impossible to disassociate from my image of Orwell doing his real-life research for Wigan Pier in Lancashire and Yorkshire—has Smith visiting a prole tavern and questioning an old man about his memories of the old days, hoping to tap into a well of ancient prole wisdom and moral fortitude that perhaps might fuel some future uprising. “If there is hope,” Smith had written in an early journal entry, “it lies in the proles.”

But when Smith does get the chance to loosen up the man’s tongue with a few pints, the fellow merely lets loose with a stream of sentimental nonsense.

“You must have seen great changes since you were a young man,” says Smith earnestly as the conversation begins.

“The beer was better,” the man replies after careful consideration. “And cheaper! When I was a young man, mild beer—wallop we used to call it—was fourpence a pint. That was before the war, of course.”

“Which war was that?” says Winston.

“It’s all wars…’Ere’s wishing you the very best of ‘ealth!”

Eventually, Winston leaves in frustration, disgusted by these beaten-down husks who “remembered a million useless things, a quarrel with a workmate, a hunt for a lost bicycle pump, the expression on a long-dead sister’s face, the swirls of dust on a windy morning”—but have no interest in their own liberation.

Orwell’s portrayal of the proles in Nineteen Eighty-Four can easily be misread as class snobbery. However, the butt of the joke in this scene is Smith, not the elderly prole who scored a free night of drinking in exchange for a few half-remembered stories. There is also an element of real envy that creeps into Winston’s inner monologue when he observes the careless freedoms that proles exercise.

About halfway through the book, there is a haunting scene in which Winston hears someone singing outside Mr. Charrington’s shop:

A monstrous woman, solid as a Norman pillar, with brawny red forearms and a sacking apron strapped about her middle, was stumping to and fro between a washtub and a clothes line, pegging out a series of square white things which Winston recognized as babies’ diapers. Whenever her mouth was not corked with clothes pegs she was singing in a powerful contralto: It was only an ‘opeless fancy / It passed like an Ipril dye / But a look an’ a word an’ the dreams they stirred! / They ‘ave stolen my ‘eart awye! The tune had been haunting London for weeks past. It was one of countless similar songs published for the benefit of the proles by a sub-section of the Music Department. The words of these songs were composed without any human intervention whatever on an instrument known as a versificator. But the woman sang so tunefully as to turn the dreadful rubbish into an almost pleasant sound. He could hear the woman singing and the scrape of her shoes on the flagstones, and the cries of the children in the street, and somewhere in the far distance a faint roar of traffic, and yet the room seemed curiously silent, thanks to the absence of a telescreen.

The scene channels Winston’s intermingled attitude of condescension and awe. As a party member, he is fully aware that the song is a mass-produced opiate whose function is to keep the proles distracted. Yet this woman also exhibits a careless freedom that Smith will never have.

This is not just a meditation on escapism that Orwell is offering us. Smith realizes that it is this sentimental spirit—along with lust, gluttony, greed and the parochial attachments of settled family life—that operate as the necessary ballast of any happy and authentic human society, which is why Oceania’s overlords (as with the leaders of any real-world totalitarian cult) try to extinguish these elements from the private lives of Party members. Nineteen Eighty-Four typically is read as a send-up of communism. But it’s really a send-up of any totalizing system of thought that seeks to perfect humanity through the ruthless application of an ideological program.

* * *

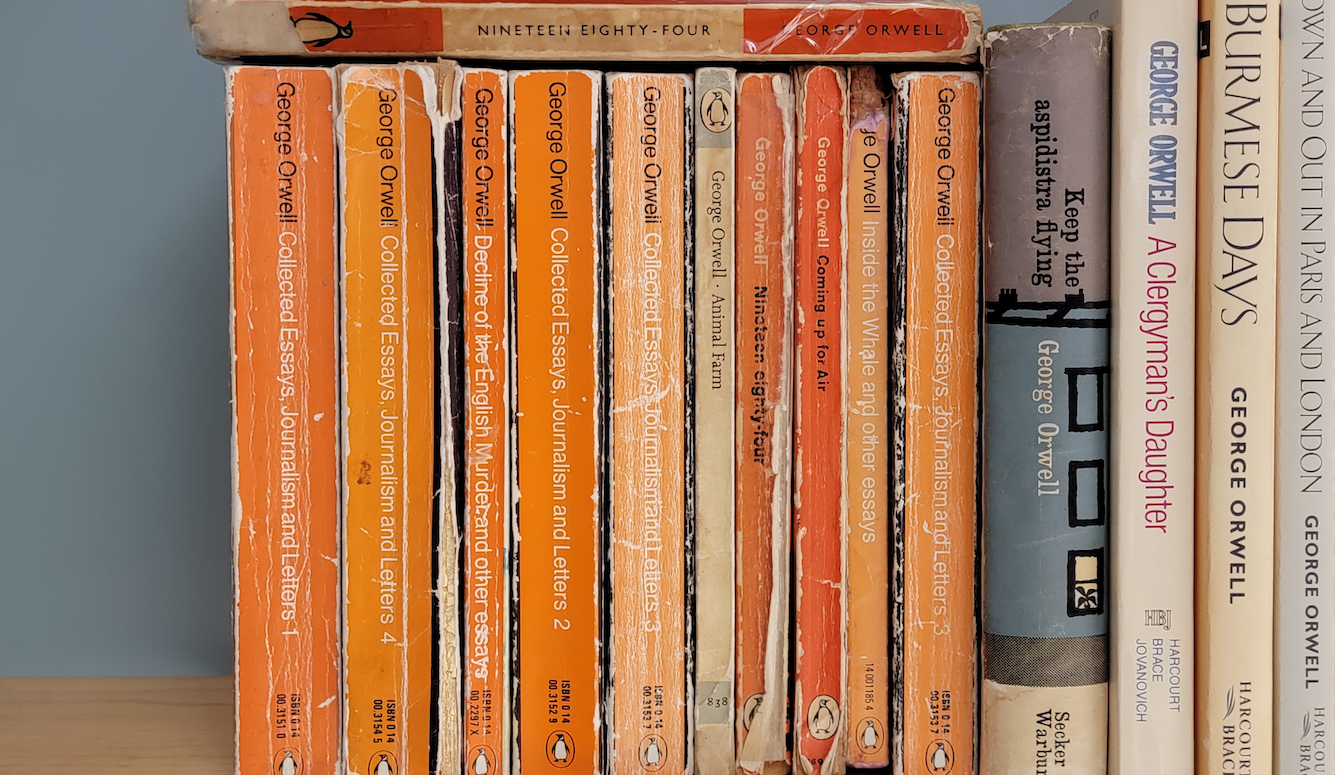

I went through my most serious Orwell phase in the summer of 1994, just before heading off to law school. I decided I was going to read everything the man had ever written, down to his surviving personal correspondence and obscure early novels. By proceeding chronologically, I was able to see how his early ideological convictions bent, and then broke, under the weight of personal experience and journalistic observation. When theory conflicted with fact, he chose fact.

Just as Smith is an anti-hero and Nineteen Eighty-Four is an anti-novel, Orwell was an anti-prophet. His main message was that we should beware of any doctrine that instructs us to ignore our five senses, betray common sense, or adopt the view that “whole blocks of millions or tens of millions of people can be confidently labelled ‘good’ or ‘bad’” (to quote a line from his essay Notes on Nationalism). And he never shied away from examining his own prejudices and insecurities. Indeed he fetishized them. The first lines of his essay on Salvador Dali, Benefits of Clergy, remain some of the most brilliant words I’ve ever seen committed to print: “Autobiography is only to be trusted when it reveals something disgraceful. A man who gives a good account of himself is probably lying, since any life when viewed from the inside is simply a series of defeats.”

By the time that summer was over, I’d come to realize that my career in law would be very short. I now knew that what I really wanted to do in life was become a writer who, like Orwell, combined the tools of journalism and literature to expose ideological movements I saw as a dangerous. On my best days, when I manage to publish something that might pass for a fourth-rate version of one of Orwell’s first drafts, I imagine this project to be noble, perhaps even heroic. Which, as Orwell would be the first to tell me, is a delusion.

“All writers are vain, selfish, and lazy, and at the very bottom of their motives there lies a mystery,” he declared in the last paragraph of his essay Why I Write. “[It] is a horrible, exhausting struggle, like a long bout of some painful illness. One would never undertake such a thing if one were not driven on by some demon whom one can neither resist nor understand.”

I think every human is born with that demon inside of us. And it is only a question of whether the demon awakens that determines who becomes a writer. My own slumbering teenage demon popped open one eyelid when a middle-school teacher assigned me Animal Farm, then the other when we read Nineteen-Eighty Four. By the time I’d finished Orwell’s collected works, the demon was upright on four paws, prowling my brain in a way that demanded full-time attention. On this 70th anniversary of the publication of Orwell’s masterpiece, I’m grateful not only because the author gave our society an entire language to describe the symptoms of totalitarianism—but also because he inspired me, and countless other writers, to embrace the “horrible, exhausting struggle” that gives life meaning.