Activism

Why Don't Women Vote For Feminist Parties?

It is naïve to imagine that female voters will necessarily support feminist goals, even when they would benefit from them. Feminists have known this for a long time.

From the beginning, Britain’s only feminist political party shared an odd sort of fellowship with UKIP, which was, until recently, Britain’s leading anti-EU party. Both purported to represent roughly half of the population: women, in the case of the Women’s Equality Party (WEP), and those who wanted to leave the EU in the case of UKIP. Both were orientated toward a single issue. And both were plucky outsiders in an electoral system that is notoriously hostile towards new parties. Although their policy positions could hardly have been more different, founding members of the WEP looked to UKIP as a model of what a small party could achieve.

But in terms of electoral success, the two parties diverged some time ago. When UKIP was founded in 1991, it was little more than a talking shop for a fringe group of Eurosceptic academics. Under the leadership of Nigel Farage, however, the party was transformed into a populist juggernaut. At the EU elections in 2014, UKIP topped the poll, getting 27.5 percent of the votes cast and securing 24 out of 73 seats in the European Parliament. In the most recent EU elections, the Brexit Party—also led by Nigel Farage and in many respects a successor to UKIP—polled 31.7 percent of the vote and won 29 seats, more than any other party in the European Parliament. Indeed, there’s now talk of the Brexit Party replacing the Conservatives, the oldest and most successful political party in Europe. A cartoon in The Times depicts Farage gobbling up Prime Minister Teresa May, leaving nothing but her signature leopard print heels behind.

My cartoon Friday @TheTimes on #TheTigerWhoCameToTea ...........#TheresaMayResignation #BrexitShambles #EuropeanElection2019 pic.twitter.com/Nr7NCUA6uZ

— Peter Brookes (@BrookesTimes) May 24, 2019

Not only was the UKIP project victorious in Britain’s 2016 referendum, where a majority voted to leave the EU, but Farage and his allies have also succeeded in reshaping British politics as a whole, bringing their concerns about immigration and national sovereignty to the fore. Truly, theirs is the great British political success story of this century—for good or ill.

And where was the WEP in all this? It also contested the European election this week, although only in London. There it managed to attract just 1.1 percent of the vote, less than the Animal Welfare Party. The WEP peaked in the 2016 London mayoral election in which it gained a modest 3.5 percent, but since then it has slipped to the bottom of the polls and seems likely to remain there. How is it that UKIP, the WEP’s dastardly older brother, has achieved so much, while the feminist party has achieved so little?

It all started so promisingly. When the WEP was founded in 2015, it attracted a remarkable number of members in their first few months. The party has always been good at branding, as you would expect of an organization founded and led by a group of successful media professionals, and they have consistently attracted glowing profiles in the national press. Looking back over their early coverage, it’s hard not to feel a pang of pity. The Telegraph described the WEP as “the fastest growing political force in the UK” only six weeks before the EU Referendum.

How quickly things change.

No one could accuse the WEP of lacking ambition. Although both UKIP and the WEP were established as single-issue political parties, for UKIP the objective was always crystal clear: to get Britain out of the EU. For the WEP, the overarching aim of achieving gender equality inevitably contains more diffuse objectives. The six stated goals of the party include “equal representation in politics and business” which is plausibly (if controversially) possible through quotas. But further down the list we get to the goal of “an end to violence against women” which makes the interminable process of leaving the EU seem like a walk in the park.

Which is not to say the WEP has not put serious thought into its manifesto. Although it has been accused of focusing too much on the interests of the white middle class women who disproportionally make up its membership, the party has offered a wide range of detailed policy proposals, including scrapping the married tax allowance and granting greater legal protections to cohabiting couples. But try as it might, these efforts have not yet won the WEP much popular support.

One might argue that the WEP does not necessarily need to win votes in order to gain influence. As an upcoming international study of women’s political parties details, such parties do have the power to alter the political landscape without attracting large numbers of votes. Simply by joining the campaign trail, women’s parties can put pressure on larger parties to better represent women’s interests.

But—and it’s an important “but”—the WEP also wants to win seats. Its original aim was to encourage a sitting MP to cross the floor, as the Conservative MP Douglas Carswell did when he left the Conservative party to join UKIP in 2014. Failing this, the WEP hoped to make headway in regional elections in which it would not be constrained by Britain’s first-past-the-post system.

Thus far this has not happened. This failure might partly be down to mistakes made by the party’s leaders. Early on, they were criticised for failing to work effectively with other political parties and they have ruffled the feathers of longstanding feminist advocacy groups. The WEP has struggled to negotiate areas of controversy within feminism, particularly the trans issue, which has been a source of significant tension. Its campaign to reform Britain’s laws regarding prostitution also proved controversial.

However, its lack of success is by no means unusual among women’s parties, dozens of which have been founded worldwide in the last century. The party with the greatest influence to date has been Sweden’s Feminist Initiative (FI). In the 2014 European elections, FI campaigned under a slogan of “replace the racists with the feminists!” winning 5.3 percent of the vote and becoming the first feminist party to send a Member of the European Parliament to Brussels. However, its success was short lived. The migrant crisis has changed the Swedish political landscape and in the most recent European election FI lost their only MEP along with 80 percent of their 2014 voters.

A brief flutter of electoral success is generally the best that women’s parties can hope for. No matter how strong their leaders are, or how appealing their manifesto promises, they will always face a fundamental problem: a lack of interest from voters.

You might think, quite reasonably, that women’s parties would be well placed to attract support. Slightly over half of the population are women and they have a distinct set of political interests. Most obviously, childbearing has a profound economic effect on women and, given that 83 percent of British women become mothers before they reach menopause, WEP policies on free childcare, protection from pregnancy discrimination in the workplace, and shared parental leave should appeal to a large proportion of the population. A woman does not have to be a radical feminist to be attracted by policies that are likely to benefit her.

But even if large numbers of women were persuaded by the WEP’s policy proposals, most people do not vote based on rational self-interest. As the political philosopher Jason Brennan puts it in his book Against Democracy, “For as long as we’ve been measuring, the mean, model, and median voters have been misinformed or ignorant about basic political information… Their ignorance and misinformation causes them to support policies and candidates they would not support if they were better-informed.” The vast majority of people do not coolly weigh up the pros and cons of voting for each of the candidates presented to them. Most voters are only vaguely aware of the policy positions of political parties, let alone the minutiae of manifestos. Added to this, our natural human tribalism causes us to make irrational decisions. All of us vote emotionally to some degree, no matter how well informed we are.

Democracy is a team sport and we choose our teams based on our identities, but with the exception of gender. On the whole, if you know a person’s class, race, education, profession, and region—perhaps also their first language and religion—you will have a good idea of their voting behavior. Working class Londoner of South Asian heritage? Labour. Middle class public sector worker living in Brighton? Green. White stockbroker living in the Home Counties? Definitely Tory.

These groupings may change over time. In the U.K., we seem to be undergoing a shift in party loyalties as voters increasingly prioritize social values. For instance, in the 2017 General Election, the affluent London constituency of Kensington returned its first ever Labour MP to the surprise of many commentators. Although the Labour Party traditionally represented the white working class, it is now attracting both middle class liberals and poorer non-white voters, a coalition that Democrats in the U.S. are also reliant on. Of course, voting behavior is subject to change in response to wider forces, but when we move our political allegiances, we move in identity blocs.

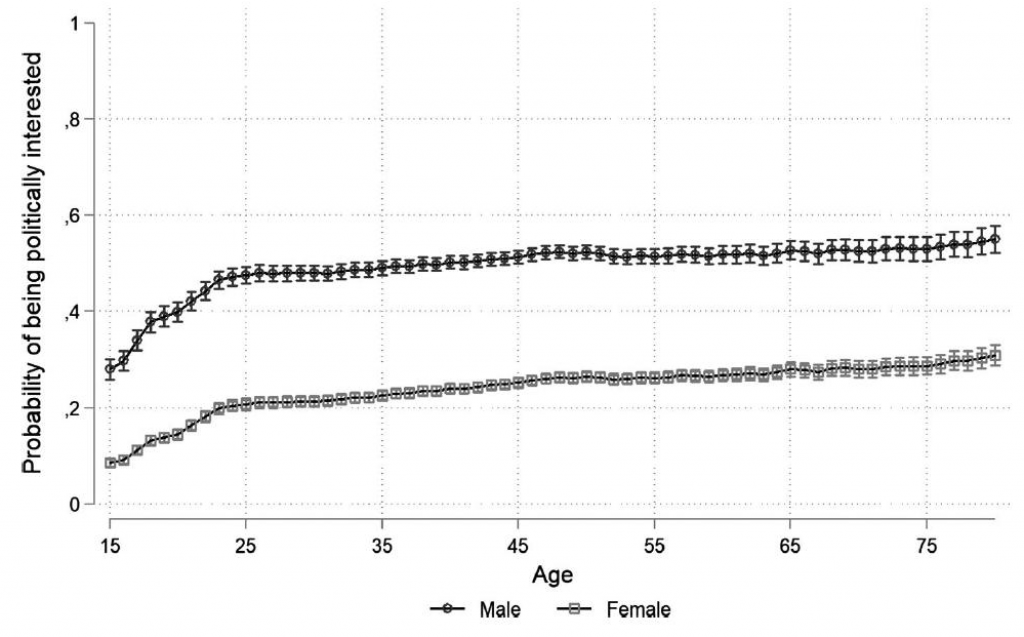

When it comes to electoral politics, however, women are not an identity bloc and they never have been. Gender has a small impact on voting behaviour, in that women tend to lean left and are also less politically engaged on average. But, on the whole, knowing a person’s sex gives you very little insight into how they are likely to vote. Although the gender gap is enough to influence an election result, sex has much less of an impact than other demographic factors. Simplistic references to “the women’s vote” overlook this fact.

In the lead up to the 2016 Presidential Election, leftist activist and actress Susan Sarandon justified her decision not to vote for Hillary Clinton, even at the risk of a Trump presidency, by insisting “I don’t vote with my vagina”—the implication being that many of Clinton’s female voters did. The phrase took off, in particular among Bernie Sanders supporters. There was a widespread assumption that Clinton’s sex would be an advantage in attracting female voters, regardless of her actual policy positions, and the women supposedly taken in by such crude identity politics were mostly held in contempt.

When Trump’s infamous Access Hollywood tape was made public, many commentators prematurely declared that this would be the end of his campaign, since there was simply no way that female voters would support a candidate who had made such lewd comments about women. A South Park episode made at the time featured a Trump-like character driving away female voters with crude sexual language. Having led a campaign based on open hatred of immigrants, he shouts after the women now disgusted by his bigotry: “Oh I’m sorry, did I offend you? I just wanted to see where your line was!” It was assumed that although female Trump supporters could stand all manner of prejudice against other groups, they would surely not stand for sexism.

Trump had no reason to worry, of course, because it turned out that his female voters were quite prepared to tolerate his attitude towards women. A majority of white women voted for Trump, particularly married women, and Clinton later suggested that they did so because of the influence of their husbands. She may well have been right.

In this regard, women are quite unlike other groups that have historically been victims of discrimination. For instance, 95 percent of black Americans voted for Obama in 2008 and turned out in record numbers to do so. As a rule, voters can reliably be expected to vote for candidates they consider to be “one of their own,” as long as we’re talking about identity categories other than gender.

Most commentators seem to be unaware of this, as we saw in the recent reporting on the new abortion restrictions imposed in Alabama. Left-leaning news outlets complained about the fact that all of the politicians who pushed through the legislation were male (and white, too), neglecting the fact that American women are on average slightly more pro-life than men.

It is naïve to imagine that female voters will necessarily support feminist goals, even when they would benefit from them. Feminists have known this for a long time. The American writer Phyllis Chesler outlined in her now-classic book Woman’s Inhumanity to Woman the many and varied ways in which women have participated in the abuse of other women throughout history. Andrea Dworkin, too, detailed the ways in which female solidarity is constantly undermined by women’s loyalties to “their” men, writing of her own Jewish identity: “I am an enemy of nationalism and male domination. This means that I repudiate all nationalism except my own and reject the domination of all men except those I love. In this I am like every other woman.”

Most political tribes live in close proximity to one another. We tend to live in neighbourhoods in which most people share our race, class, and regional identities, and therefore vote in the same way. One thing to emerge from the aftermath of the Brexit referendum is that many voters knew very few people—if any—who had voted differently from themselves. The Remainer and Leaver bubbles have significant influence and it’s easy to feel animosity towards other political tribes when they are imagined as faceless strangers.

None of this is true for women. The dream of a minority of Second Wave feminists that women would leave their husbands en masse and establish female-only communities never came to pass. Women are not an isolated group—they not only live among men, but also often love them as spouses, sons, fathers, and brothers. And that’s as it should be.

But one effect of this is that true female solidarity is vanishingly rare. When asked to choose between identifying with other women, or identifying with “their” men, most women will choose the latter option. This means that women’s political parties will always struggle to gain a significant share of the vote.

But this doesn’t mean that feminists should give up hope. We have witnessed within the last century the most remarkable progress in women’s political representation in the West. Decriminalized abortion, funding for rape crisis centres, reforms to the criminal justice system, anti-discrimination legislation, and many more landmark achievements—all this has taken place within a democratic system and without the existence of women’s political parties. We don’t need women to “vote with their vaginas” in order to effect change. A hundred years ago there was only one female MP in Britain’s House of Commons; now there is a female Prime Minister (for the next few weeks, at least, as she has announced her resignation date).

UKIP may have flourished while the WEP has failed, but feminists within Westminster have achieved just as much as Brexiteers, albeit over a longer timeframe. In fact they have achieved far more. We may yet remain in the EU, and Nigel Farage may yet sink back into obscurity. The political advancement of women is here to stay.