recent

Michael Oakeshott and the Intellectual Roots of Postmodern Conservatism

For instance, postmodern conservatives are reticent to trust rationalistic arguments made by cosmopolitan “elites” who stress that we have moral obligations to all individuals, regardless of where they come from.

To be conservative … is to prefer the familiar to the unknown,

to prefer the tried to the untried, fact to mystery, the actual to the

possible, the limited to the unbounded, the near to the distant,

the sufficient to the superabundant, the convenient to the perfect,

present laughter to utopian bliss.

~Michael Oakeshott, On Being Conservative.

In his seminal essay “The Intransigent Right at the End of the Century” in the London Review of Books, the historian Perry Anderson listed Michael Oakeshott as one of the four great right-wing thinkers of the twentieth century. Anderson acknowledges that while the other three—F.A. Hayek, Leo Strauss, and Carl Schmitt—remain well known amongst the literate public across the Western world, Oakeshott remains a somewhat elusive figure. That is unfortunate. Not only was his thinking highly interesting on its own merits, it was also ahead of its time in anticipating the emergence of postmodern conservatism.

Oakeshott’s Life and Thinking

On the surface, it might appear odd to characterize Oakeshott as a predecessor to postmodern conservatism. While the polemical thinking of today is often characterized by shrill denunciations and partisan vitriol, Oakeshott was ever the model of an impartial academic. His writings were evenhanded and curious, even where he gives in to a distinctively English propensity for biting sarcasm and sardonic wit. Moreover, although his life was framed by the apocalyptic events of the Second World War and the epic ideological contest with the Soviet Union that followed it, Oakeshott was not given to outbursts of hyperbole or grandstanding. Nonetheless, it is in his epistemological and moral orientation that one can find a specific kind of conservatism that anticipated the postmodern variants ascendant today.

Michael Oakeshott was born in 1901, the son of a socialist civil servant. As a young man he enrolled at Cambridge University, where he studied history and became attracted to the philosophical theories of the British idealists. At the time, these writers were the subject of ferocious criticism by the logical positivists led by the socialist Bertrand Russell. Although Oakeshott would later move on from the idealists’ heady Hegelian tropes, he remained sympathetic to their emphasis on history, particularity, and especially their criticisms of utilitarian reason. He served in the Second World War before assuming a series of academic appointments at Oxford and the London School of Economics. Through the 1960s to the 1980s, he wrote the political works which made him famous, including Rationalism in Politics and Other Essays in 1962 and On Human Conduct in 1975. He died in 1990 at the age of 89.

Throughout his life, Oakeshott contended with the aspirations of the rationalistic utilitarians and the expansion of the welfare state during the middle decades of the twentieth century. Classical utilitarianism originated in the work of Jeremy Bentham and his followers, and aspired to be a fully rational “science” of morality. According to Bentham, all moral questions could be resolved through an appeal to empirical facts concerning what maximized pleasure and minimized pain for moral agents. By contrast, all forms of moral reasoning that could not be reduced to this simple calculus were often dismissed by Bentham as nonsensical. As it developed, utilitarianism quickly developed a radical political edge. Figures like John and Harriet Taylor Mill were prominent early suffragettes, and in Oakeshott’s own lifetime, authors like H.L.A. Hart came to be affiliated with campaigns to end discrimination against gays and lesbians. Concurrently, many utilitarians expressed disdain for conservative efforts to prevent what they considered to be utility maximizing change. This is nicely expressed in J.S. Mill’s infamous characterization of Conservatives, uttered during a Parliamentary debate with the Conservative MP, John Pakington, in 1866:

I did not mean that Conservatives are generally stupid; I meant, that stupid persons are generally Conservative. I believe that to be so obvious and undeniable a fact that I hardly think any hon. Gentleman will question it.

The influence of these rationalizing reformers was seen in the efforts of the ascendant post-war Labour Party to construct an expansive British welfare state. Starting with the Beveridge Report in 1942, there was a growing sense that the state should assume responsibility for maximizing overall utility by securing the welfare of all citizens. Tradition and history, not to mention an emphasis on individual responsibility, were to be ignored or swept aside and technocratic bureaucrats were to rationally evaluate all social policies and practices to determine whether they effectively maximized utility.

To combat this, Oakeshott developed an epistemological and moral outlook that rivals that of Richard Rorty in his most postmodern moments. He did not deny that the reasoning deployed by utilitarians was eminently rational in most respects; it suggested that all moral questions could be answered through a hedonistic calculus deployed with utter impartiality and rigor. But Oakeshott argued that this kind of reasoning could be exceptionally destructive to the affective bases of our lives. It had little interest in traditions which could not be shown to maximize utility, even if many people had an irrational attachment to them because they emerged as part of their cultural history. In contrast to this rationalism, Oakeshott stressed the attractions of a traditionalist reason based on our commitments to a particular and historically engendered way of life. These could never be fully explained rationalistically, and certainly could not be universal. They were based on our emotional attachments to traditions and affiliated practices, in which we engaged even if they seemed to have no firmly rational basis.

Consider the practice of granting greater moral weight to the concerns people belonging to one’s own nation rather than those of others. From the hyper-rationalistic perspective of a Utilitarian, this is a highly partial way of regarding the world, reflective of an intense and superstitious irrationalism. If we are solely concerned with maximizing the greatest happiness for the greatest number of people, then entirely arbitrary factors like belonging to the same nation state cannot be granted significant moral weight. Indeed, this is precisely the argument of contemporary utilitarians like Peter Singer:

By contrast, Oakeshott firmly insisted that many of us do not wish and indeed cannot even think of morality in this manner. We come into the world embedded in highly particular cultures and engage in traditional practices which are specific to the groups with which we affiliate. Many of these practices may have little rational basis; for instance flying a particular flag or taking pride in our nation’s accomplishments even when we did not contribute to them. Nonetheless, they provide life with a greater sense of meaning. Rationalizing them away would strip people of much of what stabilized their identity and their sense of what is of morally valuable.

Oakeshott formulates much the same point in a somewhat different manner in his essay “The Politics of Faith and the Politics of Skepticism.” There he concedes that the traditionalist reason with which he is contrasting rationalism is predicated on a kind of “faith.” We morally privilege those individuals and practices emerging from our traditions because they provide us with a sense of constancy and stability. Echoing Russell Kirk’s claim that a progressive is someone who rationalistically asks “What is?” while a conservative asks “What does this mean?” Oakeshott conceded that the practices flowing from these traditions could not be defended by pure reason. But that is not their chief virtue. Traditions help us establish a continuity with the past, and so emphasize what is familiar and known in the present and future.

By contrast, a politics of skepticism must continuously criticize the present by showcasing how many of our beliefs and practices have no rational epistemic or normative basis. Politically, this leads the skeptical rationalist to demand traditions be overturned where they cannot be shown to conform to their conception of reason. As Oakeshott put it in Rationalism in Politics:

For the Rationalist, politics are always charged with the feeling of the moment. He waits upon circumstance to provide him with his problems, but rejects its aid in their solution. That anything should be allowed to stand between a society and the satisfaction of the felt needs of each moment in its history must appear to the Rationalist a piece of mysticism and nonsense. And his politics are, in fact, the rational solution of those practical conundrums which the recognition of the sovereignty of the felt need perpetually creates in the life of a society. Thus, political life is resolved into a succession of crises, each to be surmounted by the application of “reason.” Each generation, indeed, each administration, should see unrolled before it the blank sheet of infinite possibility. And if by chance this tablula vasa has been defaced by the irrational scribblings of tradition-ridden ancestors, then the first task of the Rationalist must be to scrub it clean; as Voltaire remarked, the only way to have good laws is to burn all existing laws and start afresh.

Conclusion: Oakeshott and Postmodern Conservatism

In his 1996 book, The Illusions of Postmodernism, the Marxist literary theorist wrote:

Postmodernism then, is wary of History but enthusiastic on the whole about history. To historicize is a positive move and History only stands in its way. If postmodern theory really does believe that historicizing is ipso facto radical, then it is certainly mistaken. It assumes that historicizing belongs largely on the Left, which is by no means the case. You do not need to tell the Edmund Burkes, Michael Oakeshotts and Hans-Georg Gadamers of this world that events can only be understood in their historical contexts. For a whole lineage of liberal or right-wing thinkers, a sensitive attunement to historical context, to the cultural moldings of the self, to the subliminal voice of tradition and the force of the local or idiosyncratic, has been a way of discrediting what they take to be the anemic ahistorical rationality of the radicals. Burke’s appeal to prescription, venerable custom and immemorial heritage is in this sense much the same as contemporary pragmatisms’ appeal to our received social practices, even if the former is thinking of the House of Lords and the latter of baseball and free enterprise. For both schools of thought, history—which comes down to something like “the way we happen to do things and have done so for rather a long time”—is a form of rationality in itself, immeasurably superior to such jejune notions as universal freedom and justice.

Eagleton’s observation about the odd coincidence of postmodern theorizing with a certain kind of conservatism was largely ignored, despite its galvanizing implications. Perhaps the reason was that the Oakeshottian conservatism invoked by Eagleton itself seemed like a relic of the past by that point. By the 1990s, Oakeshott himself was considered something of an oddity amongst right-wing intellectuals. He was clearly immensely learned and intelligent, but his anti-rationalism and emphasis on a politics of “faith” and emotional attachment to tradition seemed like superstition in accordance with the spirit of the age. Economically minded neoliberals like F.A. Hayek and Milton Friedman were more to the taste of conservative politicians like Margaret Thatcher, who was often eager to give her reforms a rationalistic quality. Oakeshott might have seemed a venerable artifact from an earlier era, doomed to fade out with the century he witnessed almost in full.

History has arguably disproven this conceit. Oakeshott’s thinking now seems not so much a phantom of the past as an anticipation of conservatism’s postmodern future. In particular, he argued that the basis of conservatism is not ultimately in some form of rationalism. This is because traditionalist reason provides us with a greater sense of affective satisfaction than rationalism, which can only ever destroy the meaningful attachments in our lives with its insistent skepticism and lust to know the world purely as it is. Traditionalist reason provides us with a sense of historical constancy and identity which may not in fact exist, but is reflected in our practices and commitments. This includes our commitment to groups like the “nation.” These may be highly arbitrary, but they are nonetheless how we frame our sense of who we are and what we owe to those like us. This provides a greater sense of meaning than rationalism, which for Oakeshott was an almost inhuman way of looking at things.

This position of course echoes the writings of many postmodern theorists, who were similarly keen to emphasize the impotence of reason relative to history and traditions. Perhaps the most prominent point of comparison is with the writings of Michel Foucault and Jean-François Lyotard. Both these authors stressed that the project of trying to formulate a universal moral reason had failed. Instead, we must analyze the historically contingent ways different societies and traditions understood personal and political morality, without trying to interrogate them based on some conceited rationalistic standard applicable in all places at all times. Oakeshott would not have agreed with the radical political implications they drew from these epistemic and moral positions, but his philosophical thinking largely accorded with theirs.

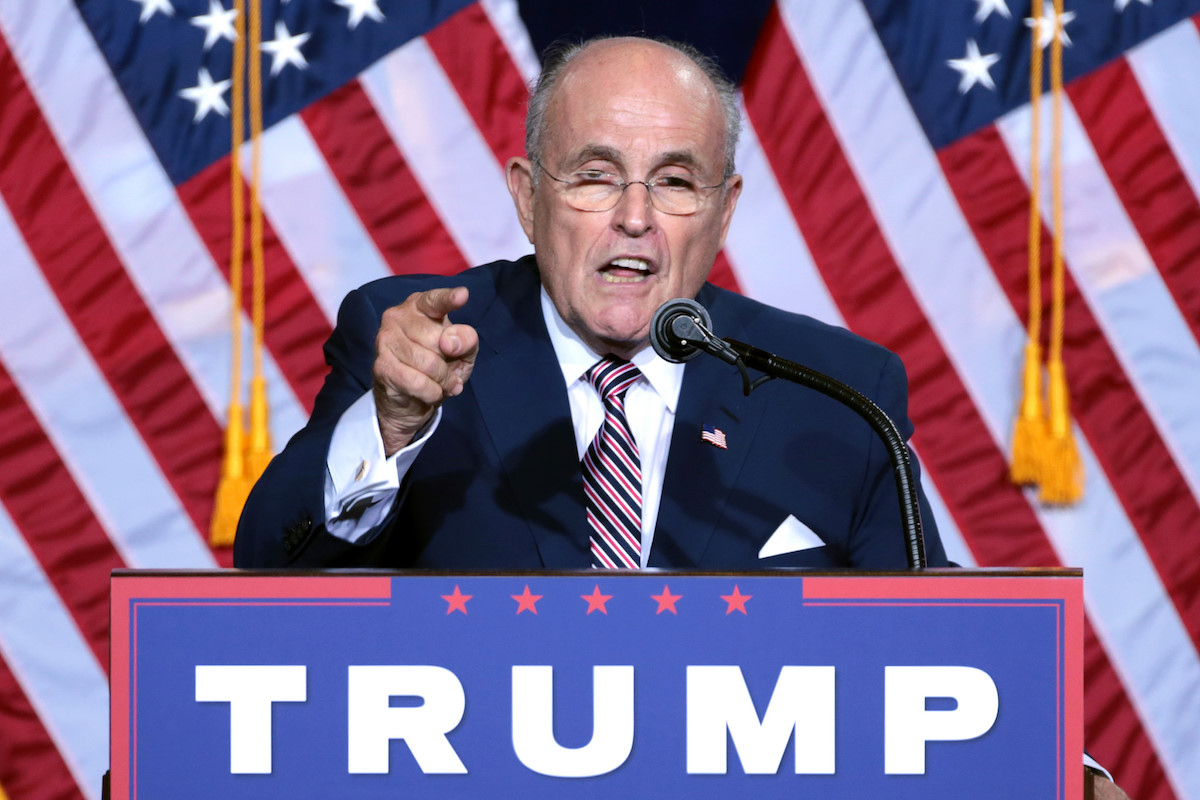

More importantly, Oakeshott anticipated the positions of many postmodern conservatives today. For instance, postmodern conservatives are reticent to trust rationalistic arguments made by cosmopolitan “elites” who stress that we have moral obligations to all individuals, regardless of where they come from. Instead, politicians like Donald Trump and Victor Orban stress that they are “nationalists” who believe that our primary moral obligations will always be to those who look and act like us. Of course, a rationalist might counter that these factors are highly arbitrary. It is purely an accident that one is born an American or Hungarian, as it is purely accidental that refugees from Latin America or Syria were born into unstable countries where they faced serious risk of violence.

Nonetheless, these factors matter to postmodern conservatives for reasons that would have been familiar to Oakeshott. The insistence that we concern ourselves with individuals with whom we have little in common is implicitly an insistence that maintaining traditional practices, and the sense of identity and meaning they provide, is at best a secondary concern next to our universal obligations. This rationalistic emphasis that we accept the “unfamiliar” into our communities, along with the skeptical injunction that we examine why we attach so much moral significance to arbitrary factors like who belongs to what nation, destabilize the postmodern conservative worldview. For this reason, postmodern conservatives are committed to combatting such positions wherever possible.