recent

Religious Faith and the Family: An Interview with Dr. W. Bradford Wilcox

In the main, religion is a force for good in the families we examined in this report—from 11 countries ranging from Mexico to Canada, from the United States to Ireland.

Bradford Wilcox is a professor of sociology and the lead author of a recently released report entitled The Ties that Bind: Is Faith a Global Force for Good or Ill in the Family? As part of my research on the psychology of meaning, I study religious beliefs and practices, so I was curious to learn more about the research in this new report. Below is an interview I conducted with Dr. Wilcox for Quillette about the report and his broader work on marriage and family.

* * *

Quillette Magazine: I’ll start by asking you to answer the question posed in the title of your report. Is faith a global force for good or ill in the family?

Bradford Wilcox: In the main, religion is a force for good in the families we examined in this report—from 11 countries ranging from Mexico to Canada, from the United States to Ireland. Partners who attend religious services together tend to do better than their secular peers and their peers in nominally religious, or religiously mixed, relationships. They are more likely to report higher-quality relationships marked by greater satisfaction, commitment, attachment, and stability, for instance. Men and women who share a faith are also significantly more likely to say they are “strongly satisfied” with their sexual relationship. The effects are especially large for women here, with women in such jointly religious relationships being about 50 percent more likely to be strongly satisfied with their sexual relationship, compared to women in other relationships.

QM: What’s going on here? Why is religion linked to these better relationship outcomes?

BW: To quote from the report:

Scholars of religion and family life often note the “norms, networks, and nomos” religious communities provide that encourage positive family functioning. That is, religious organizations provide messages and understanding about the importance of good marriages and families, and how to achieve them. They surround their adherents with like-minded people who can offer emotional support and accountability should husbands or wives start to deviate from the straight and narrow. And they may engender what psychologist Annette Mahoney and colleagues referred to as the sanctification of marriage, where marriages are imbued with spiritual character and significance. The norms, networks, and nomos associated with religious communities may be especially influential when both partners in the relationship are committed to their religious communities, privy to the same messaging, and embedded in the same social networks (i.e., shared religion has more potential to be protective than individual religion).

In simpler terms, for many couples, I think a shared faith translates into greater exposure to norms like fidelity and forgiveness, family-friendly networks that lend counsel and support when the going gets tough, and a nomos—or a religious belief system—that both buffers against the stresses of married life and encourages them to prioritize their marriage by investing their relationship, and life more generally, with tremendous meaning.

Surprisingly, religion seems to matter not just for relationships in general, but for sex as well. Another new study indicates that religious couples enjoy more commitment and greater generosity towards one another, both of which boost sexual satisfaction. What happens outside of the bedroom, then, would appear to matter for what happens in the bedroom.

QM: Does the report have negative news about faith and family?

BW: On the negative side, we did not find that religion is protective against intimate partner violence (IPV). For the men and women we interviewed, about one-in-five reported some kind of experience with IPV, defined as domestic violence, threats, forced sex, or controlling behavior, and religion was not associated with less IPV in our study. So religious faith is not a panacea when it comes to relationships.

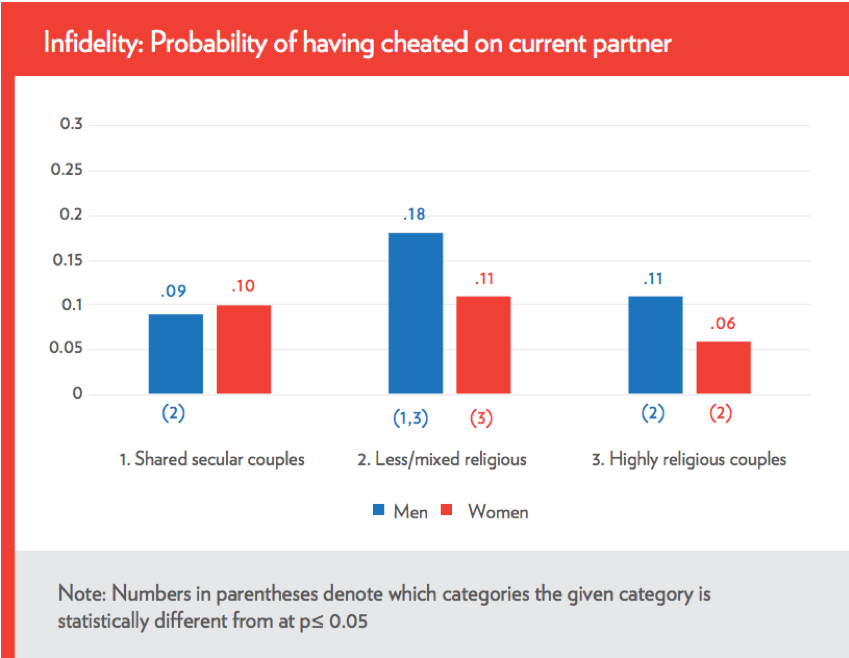

Also, we find that couples who are characterized by a “lukewarm” or mixed religious background are more likely to suffer from lower relationship quality, more infidelity, and less shared decision-making. See men’s reports of infidelity here, for instance:

It looks like a little religion can be worse for some couples than a shared secular relationship.

QM: How did your research team explore this question?

BW: Scholars from the Wheatley Institution and the Institute For Family Studies fielded an international survey of more than 16,000 respondents age 18–50, the 2018 Global Family and Gender Survey (GFGS), which was conducted in 2018 by Ipsos Public Affairs. The GFGS relies on a nationally representative sample of more than 2,000 American adults, and opt-in samples for adults from the other 10 countries in our sample that are weighted to be representative of those countries. In this report, we focus on more than 9,000 men and women in heterosexual relationships and draw on their self-reports regarding a range of attitudes, relationship outcomes, and socioeconomic factors.

QM: What finding surprised you the most in this study?

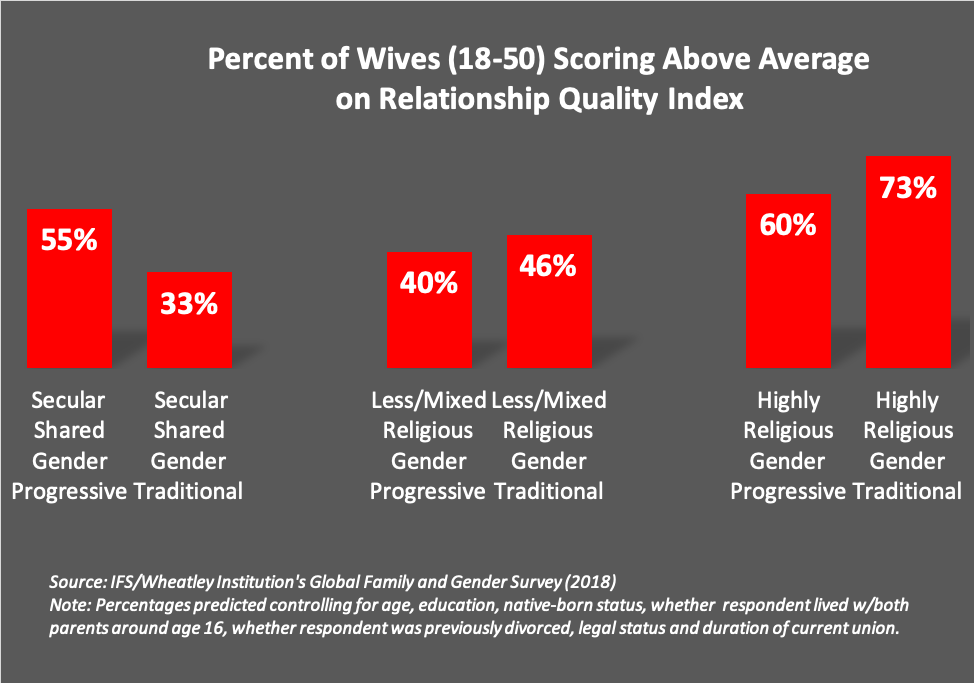

BW: Well, when we separated out our sample by religion and gender ideology, there is a J-Curve of sorts for women’s relationship quality. Women on the secular Left do comparatively well when it comes to relationship quality, as do religiously conservative women on the Right. Interestingly, women in the religious middle, and women who are secular conservatives, don’t do as well. In the United States, for instance, when we look at the share of wives who score above average on a relationship quality index that encompasses satisfaction, commitment, attachment, and perceived stability, we see a J-Curve like this:

As we noted in the New York Times, for all their differences, we think that wives at the opposite ends of the spectrum both enjoy clarity not only over gender roles but also over the importance of men engaging on the family front:

In fact, in listening to the happiest secular progressive wives and their religiously conservative counterparts, we noticed something they share in common: devoted family men. Both feminism and faith give family men a clear code: They are supposed to play a big role in their kids’ lives. Devoted dads are de rigueur in these two communities. And it shows: Both culturally progressive and religiously conservative fathers report high levels of paternal engagement.

Generally, high levels of male familial engagement translate into happier wives.

QM: As a researcher who studies the psychology of religion, I’m very familiar with the large and methodologically diverse body of literature spanning the social, behavioral, and brain sciences that indicates religious beliefs and practices are associated with a wide range of positive physical, mental, and social health outcomes. And yet, in academia, media, and secular society more broadly, religion is often treated as being of little value or even bad for people. I’m curious if you have any thoughts on this disconnect?

BW: Yes, I think the suspicion of religion is directed primarily towards the more traditional norms related to gender and sex supported by many of the great religious traditions. Religion is seen as an antediluvian force in society.

Bradford Wilcox is director of the National Marriage Project at the University of Virginia, a senior fellow at the Institute for Family Studies, and a visiting scholar at the American Enterprise Institute. You can follow him on Twitter @WilcoxNMP