death

She Did Not Go Gently

The placebo effect is real. It’s measurable. It’s why we have placebo trials in medical research—because the hope buried inside that sugar pill has a measurable medical benefit. Hope is literally medicine, and it’s powerful stuff.

In August 2017, my wife Buffy was diagnosed with early onset colon cancer. She was 41 years old. In April 2019, she passed away. Our five-year-old daughter and seven-year-old son lost their mother. I lost my best friend. She and I were together half of our lives, married 18 of them. She did not want to die.

She was an amazingly accomplished woman. Girl Scout Gold at 16, national first vice president of the Children of the American Revolution, and president of the university chapter of the Society of Women Engineers in undergrad. Bachelors in civil engineering from Georgia Tech, masters in construction management from Stanford, certified construction estimator.

She built buildings. Big ones. Cool ones, that everybody loves. She was a talented woman in a male dominated industry. To my knowledge, she succeeded at every single thing she ever set her mind to, save beating cancer. Her face lives in the Atlanta skyline.

There was never any hope, if we’re being objective. Her first CT scan showed a major obstruction of the colon, twenty spots on her liver, two the size of tangerines, and several on her lungs. She was deep into stage four cancer before she ever got checked out. The first scan was a death sentence, and she knew it. She wasn’t dumb.

She carried a lot of anger for not getting evaluated sooner, but it probably wouldn’t have mattered. She noticed major symptoms in July of 2017, but pushed the doctor’s visit for professional reasons. In retrospect, she probably had signs as early as May, but she did what every early 40s person does—she wrote them off to aging. She thought she had irritable bowel syndrome and was going in to get some pills. The only reasonable way to catch the cancer would have been a routine colonoscopy, but nobody gets those until they’re 50. It was unavoidable, and incredibly rare at her age. And incredibly unfair.

Buffy deserved this less than anyone I’ve ever met. She was kind, warm, friendly, astoundingly intelligent, and incredibly strong. Everyone loved her. She was rarely critical, but when she was, she was always right. In the days after her passing, many different people said to me that their behaviors in the past decades have been influenced by the mere thought that Buffy might disapprove. They loved her that much.

It was unfair to her, to our kids, and to me.

My first task was to get over how unfair it was to me. My next was to mitigate how unfair it was to the kids. And my last and most important task was to beat her cancer. An unbeatable cancer. This diagnosis is the sort that will remain a death sentence five decades from now.

So the project definition shifted.

The actual project was not to survive the cancer at all. The actual project was to squeeze out as many remaining days with our kids as we could. For that, she needed hope.

Hope and Denial Are Linked

The placebo effect is real. It’s measurable. It’s why we have placebo trials in medical research—because the hope buried inside that sugar pill has a measurable medical benefit. Hope is literally medicine, and it’s powerful stuff. But in hopeless situations, hope is in short supply.

If you’re in a hopeless situation, the only way to get hope is to deny the situation. Hope and denial are linked. She told me early on, “I’m just going to be hopeful that this chemotherapy treatment will work,” which was at once bullshit and also the obviously correct thing to do, and I went along with the masquerade. But I didn’t hope and I didn’t deny, because doing either wouldn’t have done me any good. I didn’t need the placebo, she did. I needed to hold everything together, and her hope was part of the treatment plan, not the action plan. Which meant I did a lot of my grieving alone, while holding her hopeful hand.

After the colectomy, we went through three different flavors of chemotherapy cocktails, two of which worked for a bit before they didn’t, followed by a shot-in-the-dark clinical trial. I made graphs, because that’s a classic coping mechanism for engineering nerds.

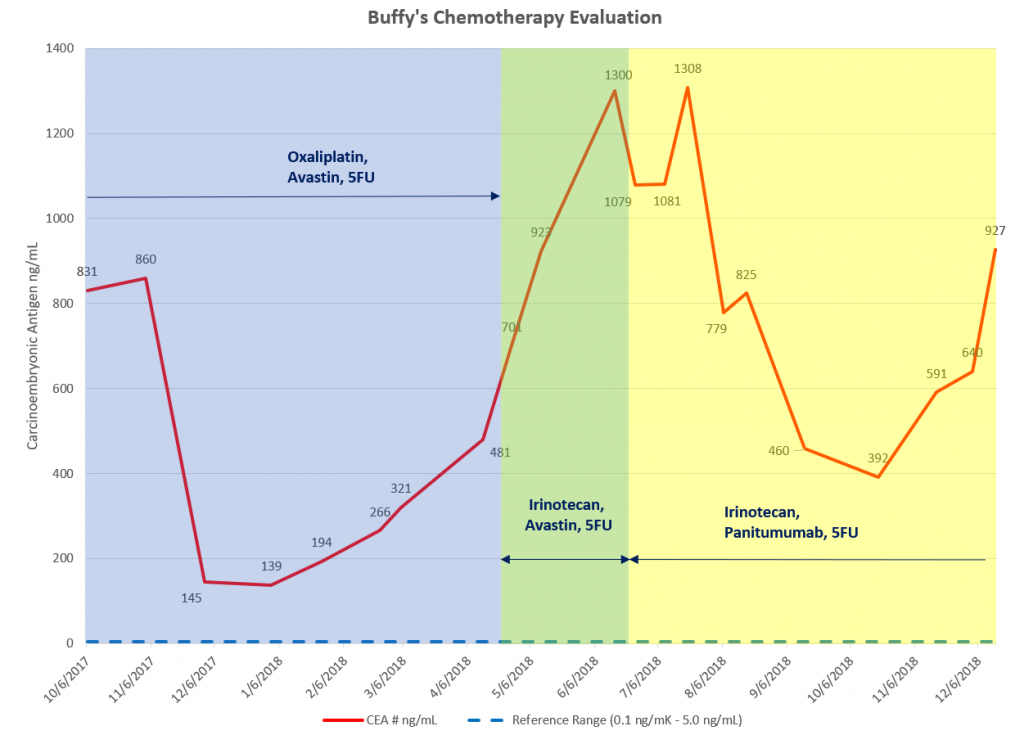

Here we see Carcinoembryonic Antigen count, which is a blood marker that indicates the presence and growth of tumors, over time. In healthy people, this marker is down around “5” or lower. We started at 831.

Chemotherapy: a three-day long infusion of chemical poison, every other week for 14 months, beating the cancer back. Buying another day with the kids. You haven’t lived until you buzz your wife’s head with your beard trimmer. She smiled her infectious smile while the hair fell into the shower drain.

I moved viciously through the stages of grief in early-to-middle 2018, while Buffy remained hopeful. The chemo turned out to be a very good training platform for the future, because every other week I was a single dad of two kids caring for a cancer patient and running a small business.

I took on a spirit animal. I needed a guiding force that dealt with tragedy while still getting things done. I chose “Oklahoma Dustbowl Farmer.” Those guys would bury their son in the morning and plant corn in the afternoon.

Buffy did the harder part. The chemo.

Hope expired the day she was pulled from the clinical trial. Her liver became too weak to tolerate the medicine, the tumors too prevalent. It was the second most emotional day for us of the entire stretch, behind Day One. The doctor’s visit was a shitshow. In the car on the way back from Emory Hospital, I told her, “I know you’re in a tremendous free fall right now, but I need you to know this. This was never beatable, and I’ve already fallen down this hole. You’re falling towards me, down at the bottom of this pit, and I’ve done everything I can to make for a comfortable landing.” That exchange was in the Arby’s drive-thru, waiting for a Jamocha shake. She wanted one.

We stopped at a bar on the way home. We have a local brewery called Scofflaw, which has a seasonal brew called “F*ck Cancer.” I ordered one with our lunch. It was good. I ordered another. They brought me a Hefeweizen. I hate Hefeweizen. I complained. They told me “Sometimes the bottom of the keg on IPAs gets cloudy. We didn’t pour you the wrong beer.” But they did. I asked for a Sweetwater 420. A couple minutes later I said to Buffy, “We just witnessed a metaphor, didn’t we? You order ‘Fuck Cancer,’ and they bring you a Hefeweizen.”

That was March 1, 2019. I’d had a year and a half to emotionally process her coming death, and she was just getting started with it. This was the price she paid for our shared denial. She had to come to grips with her own death on a short fuse. I tried to help her. She had other ideas.

The Fortune Cookie

I would have probably reacted differently to the cancer than Buffy did. I would have been flying around, checking bucket list items, building memorabilia for people, making whatever mark I could before I passed away. I offered her support in that, and she simply wasn’t interested. She wanted things to just be as normal as possible. The best way for her to fight it was to not think about it.

It frustrated me some, and for a long time I thought that she was simply not capable of coming to grips with her death. It was too big. But looking back, especially on the final months, I think I was wrong. She could have come to grips with it if she wanted to. She chose not to, and my job as a husband was not to push her towards an epiphany she didn’t want to have. She wanted to fight, and my job was to help her.

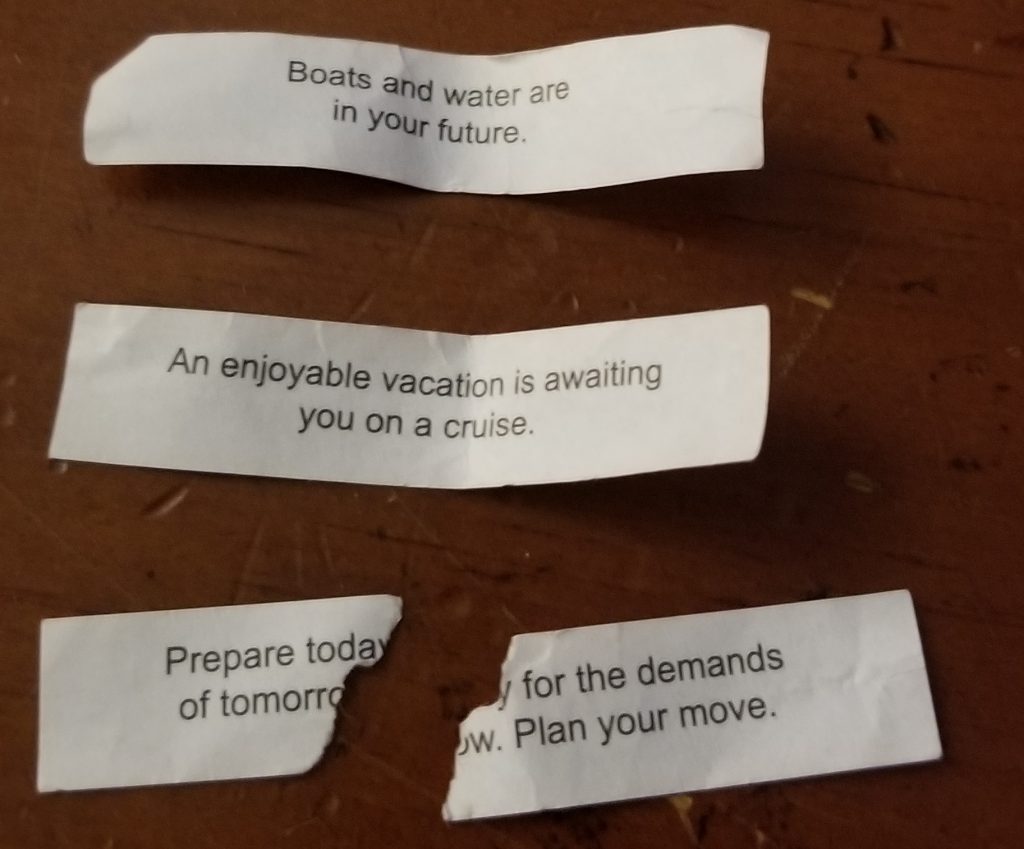

We did no funeral planning. She chose not to finish many of her projects, such as knitting the kids’ Christmas stockings, because choosing to finish would be admitting why she was finishing. We only got onto hospice care six days before she died. I don’t know where the wedding ring is. Going through her belongings after she passed on, looking for that wedding ring, I found these three cookie fortunes in her purse:

She kept the first two intact, ripped the third one, and then kept it ripped in her purse. It was her ‘fuck you’ to the situation. She was the most talented planner I’ve ever met, professionally or otherwise, saying, “No, I will not prepare.”

Last Words

In the final days, Buffy was very averse to anyone wanting to say “last words.” She cancelled all her friend visits. She told me she didn’t want people talking to her like she was going to die. She told the social worker on Tuesday, the day before she died, that she figured she had another week or two if she could just get the pain under control. Later that day, she told me the pain was about like Pitocin-induced labor contractions with no painkillers. She would know. She was on a 60mg OxyContin time release and 20mg of Oxycodone at the time. She could barely eat and had no weight left to lose. Nevertheless, she persisted.

In those final days, I abandoned my spirit animal for a better one. The Oklahoma dustbowl farmer paled in comparison to Buffy.

There was a moment on the Tuesday when we had a scare. Her breathing slowed tremendously from some of the breakthrough pain meds we had administered, and I held her hand, stimulating it. I didn’t know if she was gone or not. When she came out of it, I said this:

If you see a tunnel, go to that tunnel. If you see a light, go to that light. If that light is a benevolent force that reviews your life, know that your life was wonderful. If you see anything I did that was hurtful to you, please forgive me, and know that I forgive you. You go to that light, and you wait for me. I’ll meet you there, just not today. I have to stay and finish what we started.

And I freaking lost it. All that stoicism came crashing down. Couldn’t say another word. She fought one more day.

After

It seems to me that stoicism is, in its purest form, nothing more than “keeping it together when shit needs to get done.” My wife taught me there are different ways to do that. While I accepted, grieved, and planned, she denied, hoped, and fought.

What do we learn from death, and from our choices in trying to deal with it? How do we know we did the right thing? Maybe I did everything wrong. Maybe we did everything wrong. That’s the problem with terminal cancer—there are no do-overs. No learning from your mistakes. Nobody gets good at this. But I think our decision to leverage that denial-hope link was the right one, because I don’t think Buffy knew how to do anything else but fight anyway.

She did not go gently.