Health

How I Lost My Partner to a Parasite

"This monster isn’t David. It’s a parasite of some kind. You see, another consciousness inside him. This thing burrowed into David’s brain … and has been there, feeding off him ever since." - Loudermilk, FX Legion.

I have given only the first rough outlines of a province of a great terra incognita, which lies unexplored before us, and the exploration of which promises a return such as we can at present scarcely appreciate.

~Johann Steenstrup, Danish zoologist, on parasites (circa 1854)

This monster isn’t David. It’s a parasite of some kind. You see, another consciousness inside him. This thing burrowed into David’s brain … and has been there, feeding off him ever since. ~Loudermilk, FX Legion.

Some lose a lover to a younger woman or an irreversible illness. I lost my partner to a parasite named Edwin. Imagine watching someone you love slowly die—except they’re still alive, still walking around, and still functioning. This is what it must feel like losing them to some kind of cult. Except that intervention and deprogramming can revert them back into the person you knew. And, although reversing a parasite invasion is possible, my now-ex ultimately didn’t care to do so.

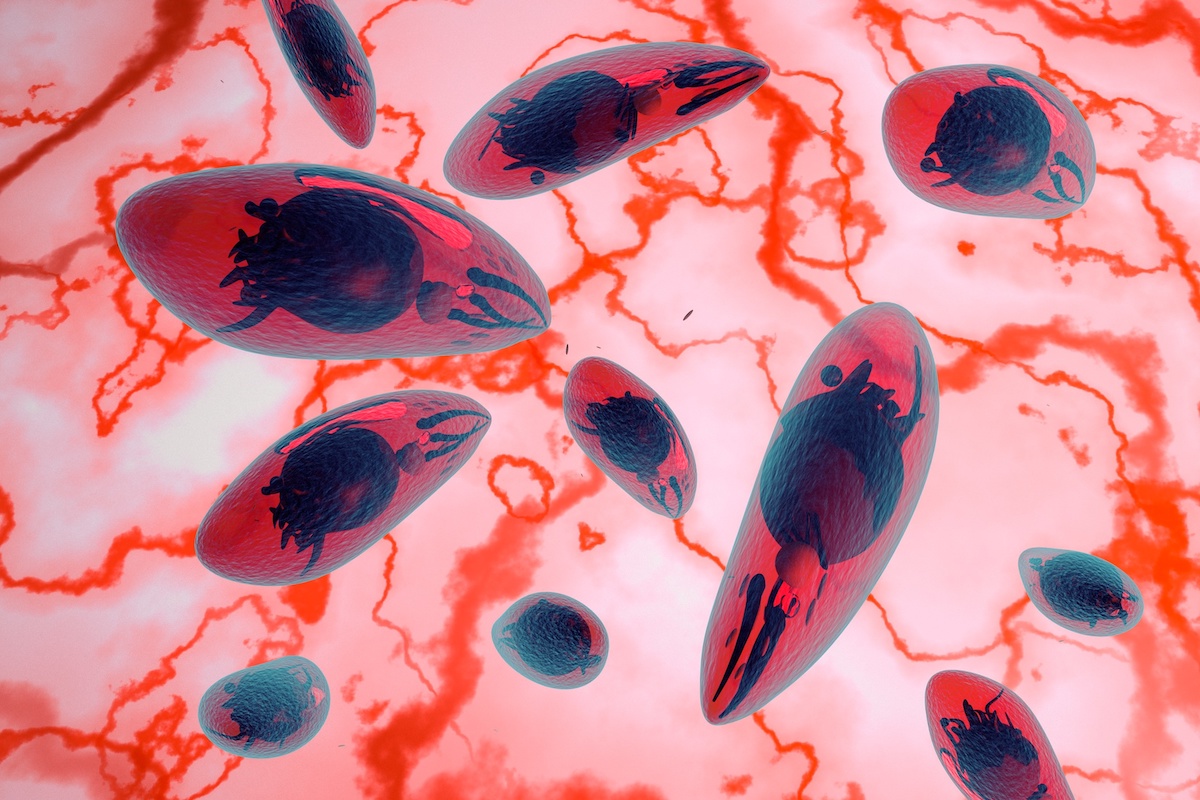

I often find it hard to believe myself, which is when I have become thankful for cognitive dissonance. Yet the scariest monsters remain those that actually exist. Contrary to what you may believe, parasitic creatures are not only found in Third World countries. These unwelcome microscopic stowaways are far more common than we realize. In fact, these “highly adapted creatures are at the heart of the story of life,” writes author Carl Zimmer in his book Parasite Rex, Inside the Bizarre World of Nature’s Most Dangerous Creatures. “[They’re] clearly designed to live their entire lives inside other animals.”

The majority of animals on earth are host to at least one parasite in their lifetime. In the United States alone, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has identified five parasitic infections that affect more than 60 million humans. My story, then, is not so unusual. Parasites are so abundant that in some environments, they collectively outweigh the total biomass of that ecosystem’s top predators. Some parasites cause relatively few negative effects for their hosts, but plenty of parasites are much more disruptive tenants. They can burrow in your brain and change you forever.

Confused? Let me use pop culture to illustrate. In Season 1 of the FX television series Legion, the main character, David, is possessed by a mutant “devil with yellow eyes”—the Shadow King; a parasite that lives inside and feeds off of him. As this malevolent creature grows stronger over time, it infuses itself into David’s psyche, living there so long it becomes part of the mental wallpaper in his brain. When presented with the opportunity to rid himself of the Shadow King, David questions whether he even wants to. They have been together so long, David wonders who and what he would be without the parasite.

Like David’s lover Syd, however, I was more concerned with obliterating the parasite and getting my partner back. Unlike in Legion, however, I didn’t have the privilege of a team of mutant Marvel super agents or access to a metal halo device to place around James’s head, temporarily isolating the parasite from his mind while I hacked a more permanent solution.

Science Friction and Lost Love

I first met James in 2004 on Craigslist. Not in the personals; he was looking for a researcher and writer and, out of 250 applicants, he hired me to develop documentary ideas. I even tracked Julian Assange in Iceland, before WikiLeaks became a global sensation and he opted to live in London’s Ecuadorian embassy until his arrest last week. For six years, up until late 2010, my relationship with James remained strictly professional, until we unexpectedly fell in love.

James was the first man I’d ever lived with. It was during our first year together in 2011 that we dreamt up a co-venture in the Dominican Republic, and soon after started an online health and wellness magazine and marketplace. When we were together, we’d work together, often in silence. I was alone but I was with him. Every night, we fell asleep curled up in each other’s arms. Over the course of several years, we built our startup into a million-dollar company. The goal was to run it from anywhere we wanted. And that it what we did, from places like Puerto Rico, Costa Rica, Greece, Italy, Miami, and Montreal.

He traveled often, and during one of these trips he wrote me the following note:

A coyote howled in my heart,

A full moon filled me, bright,

drowning all other creatures of the night, when you just sat there, to my right.

We worked well together. Until we didn’t.

Crazy Cat Ladies And Small Blobs With Big Sway

Dive into the wild and weird world of parasites and you’ll undoubtedly encounter Toxoplasma gondii, arguably the most infamous and studied neurological parasite. It’s a tiny but powerful protozoa which crawls its way into the brain and can radically alter the behavior of its varied hosts. This exemplary tale of survival begins with T. gondi, aka Toxo, setting up camp in a rat.

“Once they’re safe and warm in the guts of their temporary hosts, the oocytes morph into tachyzoites, unassuming little blobs that can really do some damage,” writes Ben Thomas. “Those tachyzoites migrate into their hosts’ muscles, eyes, and brains, where they can remain hidden for decades without doing much of anything.”

Infected rats eventually become sexually aroused by the smell of an entirely different species: the cat family (Felidae). Rats then engage in fatal feline attraction and inevitability meet a horrible death. By doing so, they release the tachyzoites into the next host, which then pass through the cat and back into the environment. Infected cats excrete billions of infectious Toxoplasma oocysts.

From there, they can jump to the ultimate host: humans, who can become infected as owners scoop cat feces out of the litter box. Rat. Cat. Human. Brilliant. One small bug able to exert incredible influence over a host billions of times its size. Researchers estimate that as many as 30 percent of the human population—more than 2 billion of us—are carrying T. gondii tachyzoites around in our brains right now. Most of us have no idea, because the parasite often causes no symptoms at all. Until the day it strikes. T. gondii has been implicated as a contributing factor to chronic psychological disorders. Studies have linked Toxo infections to Parkinson’s, cryptogenic epilepsy, migraines, and schizophrenia.

Goat Balls and Voodoo Rituals (Phase 1)

It all started around June 2013. James and I had been together for two years when he got a gig in Haiti. He would become one of the first white men to journey to a sacred mountain to honor Bondyè, the Creator God. His mission was to film a voodoo ritual, alongside Vodouisants, high priests (houngans), and priestesses (mambos) deep inside a remote Haitian cave. The servants of the spirits lucky enough to be possessed would sacrifice a goat and then eat its testicles. James filmed the ceremony while standing in blood, feces, disease, mud, and spirits.

Within five days of his return, he had lost 10 pounds. It was coming out of both ends and it didn’t take long for me to conclude he had parasites. I urged him to get his stool sampled, which he did. Western Medicine identified three parasites and my naturopath’s lab identified four. James had taken Cipro, an antibiotic, while in Haiti for food poisoning, and another dose upon returning. He was considering a third round of antibiotics until my naturopath advised him against it lest he face a “total immunological breakdown.”

“The bugs inside you will be able to learn, adapt, and mutate,” she warned. Instead, he began taking a natural anti-pathogen formula called SCRAM, which kept things stable for a while until he went through several bottles. From this point onwards—during what I describe as the first of three phases in the parasites’ evolution—James started getting ill about once a month. He’d undoubtedly get fever, diarrhea, and stomach cramps, spending a few days curled up in a fetal position, incapacitated in bed.

“To survive a parasite must usurp the resources of another organism to grow and reproduce,” according to an article entitled “Rewiring the Brain: Insanity by Parasite.” Many parasites accomplish this task by partially debilitating their host while still keeping it healthy enough to continue providing shelter and nourishment. I noticed that symptoms were activated around the full moon, which is when the freeloaders—who, by the way, absorb our nutrients and excrete toxic waste—swell with water and have sex parties in our bodies. Mature tapeworms, for instance, can lay a million eggs per day and roundworms, which afflict 25 percent of the world’s population, can lay 200,000 eggs daily.

“Parasitic infections can disable normal mental function by depleting the host of essential nutrients, interfering with enzyme and neuroimmune function, and releasing massive amounts of waste products, enteric poisons, and toxins, which disable brain metabolism,” says Dr. James Howenstine, M.D., board-certified specialist in internal medicine.

James had a recurring dream. It was fairly nondescript; he was at a beach party with some braless women in South America when he felt a strange presence. He said it was as if something had hacked into the dream. He noticed a figure loitering a few hundred feet away on the periphery of his vision. When the figure noticed James staring at him, he edged out of reach. On the third night, James got close enough to identify the figure: he said it looked like Don Fino Sandeman, the caped man from the sherry bottle! Enter Edwin.

Stool Samples and Mania in Cannes (Phase 2)

Oh-oo-oor. Oh-oo-oor. I awoke at 7 a.m. to pigeons noisily making a nest on our roof, and James hovering over me. He looked distressed. At the time we were living in his friend’s penthouse in Cannes. Vivid hallucinations had kept him up all night. Apparently, a Jabba-the-Hutt-like creature had been sitting on me while I slept. Around this period in late 2014—what I call Phase Two of the parasite’s evolution—James’s sleep was often disrupted. Many nights he barely slept, contending that sleep was simply “a mindset” needed only by the weak-willed.

Over the previous several months, I’d noticed his heightened agitation and mood swings. It was also during this phase that James announced that his parasite had a name. “Edwin,” he announced, didn’t like to be called “a parasite.” This term, he explained, didn’t properly capture its nature. I asked Google if parasites can cause hallucinations. Indeed, they can. Parasites can cause personality changes and psychosis, including delusions and auditory hallucinations.

“Just like any other brain injury, any infectious agent that damages the brain has the potential to disrupt mood, behavior, and personality,” says Bill Sullivan, a Showalter Professor at Indiana University School of Medicine. I suspected the parasite was causing James’s personality to change. Parasites can influence multiple facets of host phenotype, including physiology, behavior, and biochemistry.

“Because pathogens want to spread to other hosts, one way they can do this is through behavioral manipulation,” added Sullivan. The behavioral manipulation hypothesis predicts that parasites can change a host’s behavior in a way that benefits the parasite and not the host. Or their loved ones for that matter. James tentatively collected a new sample but I was noticing that the strength he needed to fend Edwin off was declining. And so the test tube sat in the fridge for two weeks before I eventually threw it away.

Life Lessons from a Parasite

“Most people who hear the word, visualize a worm that hasn’t shaved for weeks, with tiny antennas, living in a cabin in your brain or colon, chewing your guts out. But nobody really knows who ‘he’ is, or that he sometimes takes more than the shotgun seat,” James wrote of Edwin. Unlike most hosts, James was aware of Edwin’s presence and, as health-oriented journalists, we openly discussed Edwin’s progress with fascination.

“It’s impossible to cover all examples of parasites controlling the minds and bodies of other animals. Indeed, there may be many cases that have yet to be discovered,” according to Amanda Pachniewska, founder & editor of AnimalCognition.org. Besides Toxo, there are parasitic worms that turn crickets into “suicidal maniacs,” making them jump into the water where the worms need to go to breed. They also manipulate the crickets to silence their chirping. And then there’s the fungus that zombifies ants and wasps that enslave cockroaches six times their size by injecting and enslaving them with mind-controlling venom. There are also the thousands of other parasites we know very little about.

If these parasites are able to screw with other species’ brains, is it that strange to believe that a microscopic puppeteer was beginning to pull the proverbial strings of the man I loved?

Parasitism: The Most Common Way of Life on Earth

James officially broke up with me three years into our relationship (around end of Phase Two of the parasitic invasion), stating that he’d outlawed them. “What do you mean?” I replied. “Everything is a relationship. You’re relating to your omelet right now.” Shortly afterward he left Los Angeles and moved 5,773 miles away.

We then developed what I regarded a “distancer-pursuer” relationship —I pursued the established relationship while he distanced himself. This resulted in a lot of tears and travel. As Edwin grew and mutated, it became clear that he didn’t like me much. It was as though he knew that I stood between him and the energy he was draining from James’s heart. “Who is this?” I’d occasionally write. “Is this James Or Edwin?” Sometimes I received a reply. At others, the silence provided an even louder response.

A psychologist might simply chalk my tale up to lunacy or a perhaps a shared delusion; James’s behavior could be “bipolar” or just garden variety asshole-ishness. Similarly, in Legion, David is initially misdiagnosed with a mental health issue. “The brain is a ‘privileged site’ for many parasites,” states Joanne Webster, a parasitology researcher at Imperial College, London. “And that really challenges the concept of free will—after all, is it us or our parasites who ‘decide’ our behavior?”

Beliefs Beyond the Norm

If you still have trouble accepting that a parasite can commandeer a human mind and seize control of its will, consider that 99 percent of our cellular count (100 trillion) is made up of something other than human DNA. That’s right, you are more bacteria than you are you, making us all minorities in our own bodies. Bacteria in our guts dictate brain cognition, mood, and health. And since we are all composed of chemicals, who am I to judge James’s parasite-altered reality?

Studies on the battles between parasite and person waged in the human body are remarkably scant. “Research into the potential neurological consequences of brain infection in humans is ongoing, although it is very challenging,” adds Sullivan. And if you want to try and measure a parasite’s capacity to erode a loving connection, good luck—that data is even more remote.

“There is no evidence either way, but it’s unlikely,” states John Hawdon, Ph.D., Associate Professor of Microbiology, Immunology, and Tropical Medicine. Nevertheless, I remain convinced that Edwin carved out a section of James’s heart and set about securing complete dominion. Without someone tugging at his heartstrings, James was infallible.

Superpowers Fully Integrated (Phase 3)

“I’m you. I’m me. I’m everything you want to be,” the Devil with the Yellow Eyes tells David in Legion’s first season. By now, the parasite has completely infested David’s body and mind. More Devil than David, he uses his powers to systematically wipe out an entire section of the shadowy governmental task force known as Division 3.

I surmise that the phases of integration vary in humans, compared to, let’s say, a cat or a cockroach. Since humans have considerably longer life-spans (and are larger), Webster et al speculate that “one could reasonably propose [they] may be more susceptible to developing ‘unselected’ pathological behavioral changes simply as a byproduct of their extended durations of infections.”

It took about four years for Phase III to announce itself. James still possessed oodles of charm. Meanwhile, his cognition and physical capabilities only seemed to improve. Creatively, mentally, and physically, James was off the charts. He had evolved into a superbug of sorts. He inhaled information, which he retained and integrated into beautifully creative stories I edited. He could swim out a mile into the vast ocean and loop around a Greek island with ease. I marveled at his prowess.

Essentially, parasites evolve to out-maneuver their host. In response, the hosts evolve better defenses, and the resulting feedback loop is a veritable arms race known as co-evolution, according to Pachniewska. It may seem strange that parasites can have a positive influence. But consider that causing its host to die quickly is not particularly helpful, especially when certain parasites jump into the ultimate frontier—a human body.

Does evidence exist in the animal world of host-parasite interactions, during which the infected cope better and develop superpowers of sorts? It does. For instance, toxo-infected rats become braver, and heedless of danger. A recent research study indicates that this parasite may actually be a source of increased dopamine. Meanwhile, by modifying particular receptors, the ichneumon wasp enables spiders to weave an optimized cocoon web that is stronger with more durable support. And a recent study, shows that, when infected with parasitic worms, Artemia brine shrimp actually have boosted abilities to survive arsenic-laced water. They also produce more antioxidants.

“I’m the magic man,” David cockily declared toward the end. As I witnessed the final phase of colonization, Edwin went from being an invader to what James now described as a “high priest.” Edwin was no longer an “enemy” but a “co-inhabitant.” The two of them had apparently worked out a living situation that suited everyone but me. The parasitic nature of our interaction finally caused part of my own heart to suffocate and die. James was collaborating with the critter, and I was frozen out.

“Edwin is getting the better of you,” I offered. “Stop talking to Edwin in a demeaning way, you have no idea what you’re talking about,” he said when I asked why he’d stopped trying to kill the parasites. “I’m not fucking boyfriend material or a life partner. Do I have to carve it on copper?” Was this the same man who once told me I filled him with the glow of the full moon? And so I surrendered. I stopped plotting ways to annihilate Edwin with ayahuasca, exorcism, coffee enemas, strict detox, or love. Parasites usually reproduce quickly to maintain the upper hand; Edwin was keeping a firm grip on his host. He was the master now.

Perhaps you think that this parasite was simply an excuse, and that James is an insufferable narcissist who never loved me at all. It might certainly appear that way to the observer. While I could accept that he no longer wanted to be with me, the underlying aggression was perplexing. Edwin seemed to be rewriting James’s memories, or, at the very least, disfiguring his perception.

The love of my life is no longer tethered to a reality I recognize. Regardless of the true impact of this passenger named Edwin, I was no longer his lover, his partner, or even his friend. The full moon did end up filling James with its light, but I was unable to drown out all the other creatures of the night.