recent

Has the Postmodern Revolution Come Full Circle?

This new orthodoxy arrogates to itself divine authority to make truth claims on the basis of consistency with its asserted principles, and these are held to be immune to disproof or falsification by reason or evidence.

While discussions about the philosophical foundations of judgements of right and wrong are often framed in terms of rational versus irrational perspectives—those based on the enlightened values of science and reason versus those based on authority or faith—this is not altogether an accurate view of where the real centre of moral debate currently lies. The game-changer has been the hegemony postmodern ideology has established over most debate about public policy and morality. This assertion may come as a surprise to many who are aware of the existence of a philosophical perspective called “postmodernism” but do not see it as having much to do with how they frame their moral judgements or how society around them is ordered. They would, I suggest, probably be wrong to believe so.

It is important to recognise that postmodernism arose not as a logical corollary of the efforts in the Enlightenment period to establish a rational foundation for addressing moral dilemmas and resisting the tyranny of religious and traditionalist worldviews in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, but as a rejection of that project. While Hobbes, Locke, Bentham, Hume, Kant, Hegel, and Feuerbach vied with one another to provide a theoretical foundation for moral discourse, ultimately none was able to prevail.

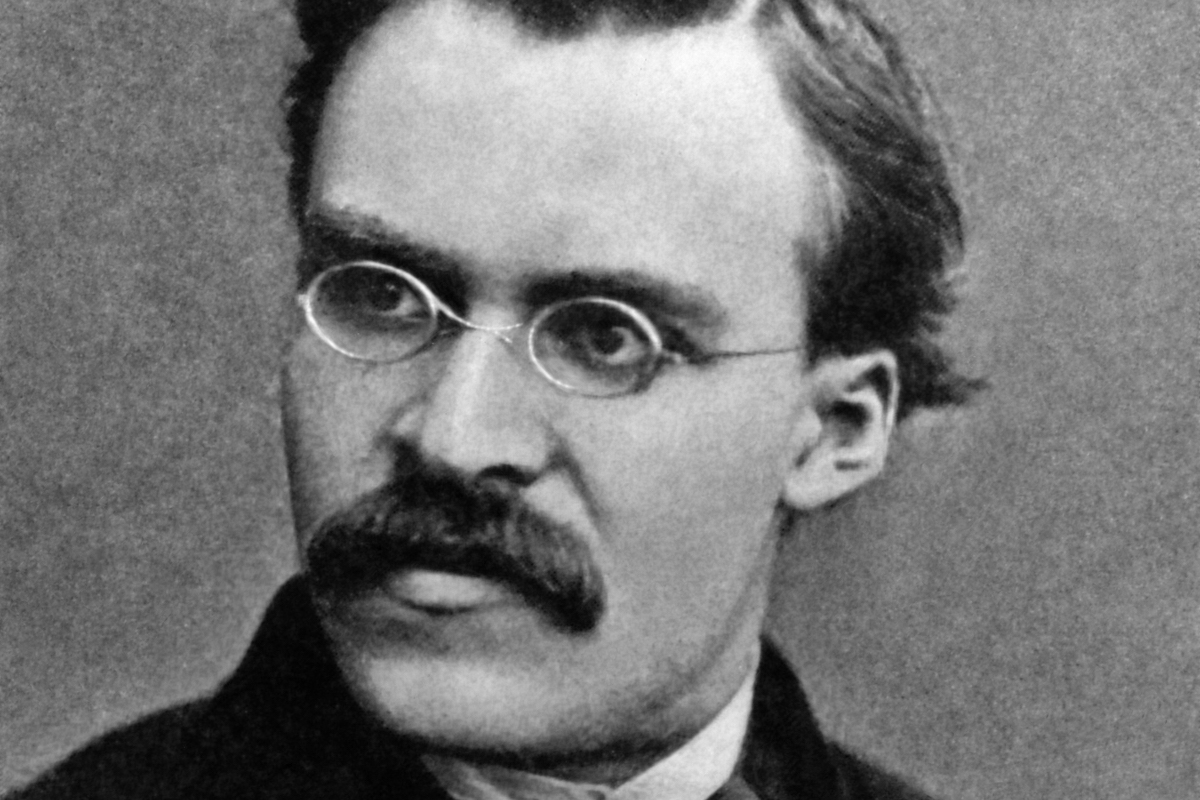

The counter-Enlightenment’s most perceptive thinker was probably Friedrich Nietzsche. His portrayal of a madman running around with a lantern proclaiming that God was dead parodied the Enlightenment philosophers who looked to replace traditional values with a new value system which pared away the superstition and retained the essence; but that there was no such essence. Freed from the constraints of the prior expectations of our peers, we are free to steer whichever course we choose.

Postmodernism builds on this insight, asking us to consider that there are no objective standards of right and wrong, only differences of perspective. According to the Encyclopedia Britannica:

Reality, knowledge, and value are constructed by discourses; hence they can vary with them. This means that the discourse of modern science, when considered apart from the evidential standards internal to it, has no greater purchase on the truth than do alternative perspectives, including (for example) astrology and witchcraft. Postmodernists sometimes characterize the evidential standards of science, including the use of reason and logic, as “Enlightenment rationality.”

This point of view is often portrayed as moral relativism, but this misses an important feature of the postmodernist position: although it holds that there is no single correct point of view on questions of right and wrong, all points of view are not necessarily equal in validity. Indeed, echoing Orwell’s critique of communist society in Animal Farm, some points of view are in practice “more equal than others.” For, as stated above, values are thought to arise in practice in “discourses” taking place in different social groups or communities. And some groups have greater power or “hegemony” to impose their view on other relatively disempowered groups. Without taking a position on whose views are more correct between the relatively more or less powerful group, postmodernists argue that it behoves us to take the side of the relatively disempowered group so as to help redress the intrinsic injustice of the situation.

So the conversation moves from one about being right to one about having rights. While a traditional perspective on human rights would be to argue that all human beings possess rights equally, the postmodernist position is that greater rights have to accrue to the relatively disempowered and so greater emphasis should be given to defending their values. From here springs the concept of group rights: women’s rights, gay rights, transgender rights, black rights, Muslim rights, and so on. It is one of the great achievements of the postmodernist agenda that, without any need for moral discourse, it has become possible to dismiss almost any moral position portrayed as disrespectful to any of those group rights, particularly if that moral position can also be portrayed as promoting the interests of some relatively more powerful group.

Not surprisingly, this approach leads quite quickly to inconsistency and even incoherence. For example, it is often argued in the corporate environment that “diversity” policies are necessary to ensure that the best people are chosen, by which is meant a sufficient number from relatively disempowered groups. But if that is one’s position, one needs to argue that members of different groups bring different talents and perspectives to the table by virtue of their belonging to those different groups, so there is a fundamental inequality between groups that demands to be recognised. This it would appear is acceptable if one were to suggest, say, that women bring a greater degree of empathy into leadership than men and should, on that basis, be favoured more than at present. But if one were to suggest that men by virtue of being men are more likely to have some quality or qualities that qualify them for leadership, there would be outrage and claims of sexism or misogyny. Whether or not any of the supporting claims has a basis in truth is entirely irrelevant. The morality of the issue is determined by whose interests are served by taking a claim seriously.

This has led to the rise of a new irrationalism, in which matters of fact and evidence can be swept aside in favour of a politics of identity elevated as the determining principle in disputes between competing moral perspectives. Just as within nineteenth century European society, as Nietzsche argued, Christianity exercised hegemony on the basis of authoritarian structures enforcing a morality which society internalised as the natural order of things, postmodernism has achieved a similar hegemony by virtue of backing up its strictures with laws and regulations which carry stringent penalties, and ensuring that its point of view is taught in educational institutions, often even to the exclusion of parental rights to assert an alternative position.

Its power derives from an enforcing authority backed up with persistent indoctrination, it has effectively managed to marginalise dissenting opinions and severely curtail moral debate in the public space. This new orthodoxy arrogates to itself divine authority to make truth claims on the basis of consistency with its asserted principles, and these are held to be immune to disproof or falsification by reason or evidence. Indeed, those who forward evidence that contradict its claims are routinely vilified and marginalised. Thus, have we come full circle in recreating the very conditions that the Enlightenment set out—but, on its own terms, failed—to address.

Happily, the inconsistency and incoherence of the postmodernist perspective is increasingly being challenged by a new generation of thinkers from across the political spectrum. For example, in his essay “Trump and a Post-Truth World,” Ken Wilber notes how postmodernism has played itself out and, by attempting to create a new basis for determining truth, has ultimately undermined it.

And thus postmodernism as a widespread leading-edge viewpoint slid into its extreme forms (e.g., not just that all knowledge is context-bound, but that all knowledge is nothing but shifting contexts; or not just that all knowledge is co-created with the knower and various intrinsic, subsisting features of the known, but that all knowledge is nothing but a fabricated social construction driven only by power). When it becomes not just that all individuals have the right to choose their own values (as long as they don’t harm others), but that hence there is nothing universal in (or held-in-common by) any values at all, this leads straight to axiological nihilism: there are no believable, real values anywhere. And when all truth is a cultural fiction, then there simply is no truth at all—epistemic and ontic nihilism. And when there are no binding moral norms anywhere, there’s only normative nihilism. Nihilism upon nihilism upon nihilism—“there was no depth anywhere, only surface, surface, surface.” And finally, when there are no binding guidelines for individual behavior, the individual has only his or her own self-promoting wants and desires to answer to—in short, narcissism. And that is why the most influential postmodern elites ended up embracing, explicitly or implicitly, that tag team from postmodern hell: nihilism and narcissism—in short, aperspectival madness. The culture of post-truth.

Wilber looks forward to an evolution beyond postmodernism; to a developmental model which is more “integrated” or “systemic.” He argues that when a system is broken, as ours currently is, it reverts back to the last point at which it functioned effectively. Let’s hope he is right. Such ideas are a welcome breath of fresh air in a political culture in which the discourse revolves less and less around facts and evidence and consists more and more of ad hominem attacks on detractors and dissident voices launched from within the relative security of group identity silos. Voices of those who, like Wilber, are critical of the failings of postmodernism and emphasise the need for new ideas are increasingly being heard. This is particularly noticeable on social media, where many of the new currents in popular thought are increasingly finding receptive audiences. It will be interesting to watch how all this plays out.