Art and Culture

Here Comes the Story of the Hurricane

The subject of Bob Dylan’s famous 1976 protest song was probably guilty.

How many people who followed the BBC’s podcast series about Rubin “Hurricane” Carter were startled—or even outraged—when Carter was not triumphantly vindicated in the final episode?

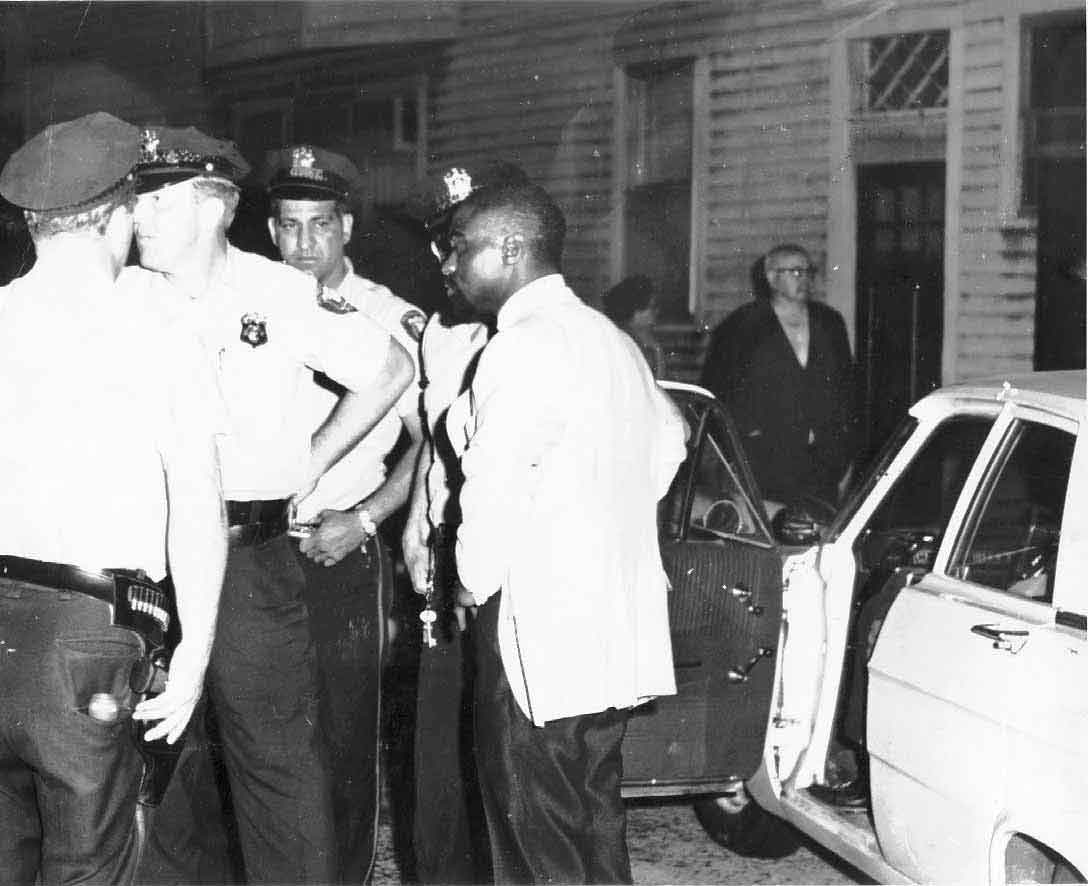

In the small hours of June 17, 1966, two black men walked into a late-night Bar and Grill in Paterson, New Jersey and opened fire on the occupants. They left bartender James Oliver and patron Fred Nauyoks dead at the scene and mortally wounded a woman named Hazel Tanis, who would succumb to her injuries a month later. Another customer named Willie Marins lost an eye in the shooting but survived. Neighbors Patty Valentine and Ronald Ruggiero told police that they had seen two black males flee the scene in a white vehicle. This testimony was corroborated by petty thief Alfred Bello who walked past the dead and the dying to empty the cash register after the shooters had fled.

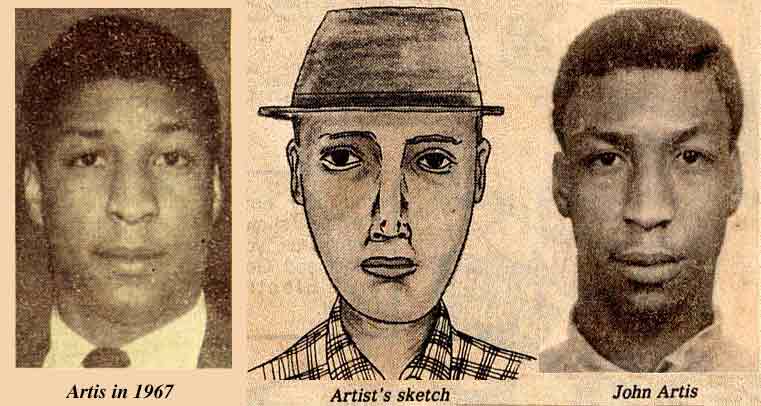

Half an hour later, Paterson police stopped middleweight boxer Rubin Carter and his companion John Artis in a car bearing out-of-state plates that matched the eyewitnesses’ description. A search of the car yielded a .32 round and a 12 gauge shotgun shell, ammunition for the weapons police later determined had been used in the shooting. Carter and Artis were eventually indicted by a grand jury and convicted of the Lafayette murders in 1967. Carter vehemently protested his innocence and his case became a cause célèbre after his 1975 autobiography found its way into the hands of Bob Dylan. Carter was retried in 1976, after the New Jersey Supreme Court ruled that the first conviction had been unfair. Despite support from Dylan, Muhammad Ali and the New York Times, the two were convicted again. John Artis was paroled in 1981, and Carter was finally released in 1985 after the second conviction was overturned and prosecutors declined to try him a third time.

Sports reporters Joel Hammer and Steve Crossman spent 18 months researching and reinvestigating the case and promised listeners of the BBC’s podcast that they would provide the “full” and “true” story. Their in-depth look at the crime provides far more detail about the murders than can be gleaned from Bob Dylan’s 1975 protest song or the hagiographic 1999 Norman Jewison film starring Denzel Washington. Dylan accused the prosecution team of framing Carter for the slayings and called them “criminals in their coats and their ties” who were “free to drink martinis and watch the sun rise.” Crossman and Hammer are likewise very critical of the prosecution; for example, they think that Alfred Bello should never have been allowed to testify. How could the life of such a man, be in the palm of some fool’s hand? And they argue that the prosecution ignored—or perhaps even suppressed—an investigation into a very plausible suspect, Eddie Rawls (who is now deceased). But they stop short of calling it a frame-up and an attempt at judicial murder.

On the other hand, Crossman and Hammer think the “racial revenge motive” was a reasonable one. The very first newspaper accounts of the slaughter at the Lafayette Grill included the speculation that the murders were committed in revenge for the slaying, earlier that night, of black bartender Roy Holloway and this would also be the prosecution’s contention. That Crossman and Hammer now accept the plausibility of this theory is a significant concession to the prosecution’s version of events, not least because it was Judge Lee Sarokin’s rejection of this motive which led him to overturn the second conviction—the prosecution’s case, he ruled, had been based on “racism rather than reason.”

Coincidentally, on the front page of the East Bergen Record, under the murder story, there was a wire service article about Stokely Carmichael proclaiming “Black Power” at a rally in Mississippi, an event which marked the transition from the peaceful civil rights tactics of Dr. Martin Luther King to the radical activism of the Black Panthers. These two articles encapsulated all the elements of the Lafayette Grill case that continue to be debated over 50 years later. Why did someone walk into a working-class bar and slaughter the occupants? Was the black community in Paterson in a ferment that night because a white man blew off Holloway’s head with a shotgun? And what, if anything, did this have to do with the state of race relations in America at the time?

In addition to conducting lengthy interviews with people connected to the case, including Carter’s co-defendant, John Artis, Hammer and Crossman studied trial transcripts, newspaper accounts, and books in their search for answers about a case which has come to be synonymous with wrongful convictions and racial injustice. They found an unpublished investigator’s report. They uncovered a forgotten stash of cassette tapes of interviews with Carter (who died in 2014). We hear Carter’s rich, bombastic utterances throughout the podcasts, hence the podcast series name, “The Hurricane Tapes.”

While reviewing the tapes, which Carter made with his co-author Ken Klonsky for his 2011 memoir Eye of the Hurricane, the reporters came to realize that Carter wasn’t always truthful, or, as they put it, he is a “complicated” man. Consequently, they warn their listeners that Carter’s claims should be taken with a grain of salt. This—evidently unbeknownst to the BBC and their research staff—is the understatement of the decade.

Everything Carter says has to be checked against the record, and checked against what he himself has said over the years. Did he grow up in a nightmare of poverty, violence and racism, as he says on the tapes, or was he telling a reporter the truth in 1975 when he said, “I grew up at a time and in a locality where racism didn’t exist… I never knew what racism was. I grew up in a multi-racial situation.” (It is true that the violent street gang he led, the Apaches, was integrated.)

Carter’s accounts of his movements on the night of the murders were inconsistent and changed significantly from the night of his arrest to the trial a year later. He coached alibi witnesses to lie for him—but most significantly, he rewrote his entire life story to claim that he was an outspoken civil rights activist, which is why he was framed for murder. This particular lie was so successful that he managed to enlist Bob Dylan and other celebrities as supporters. Later, he attracted the loyal support of a group of people called “The Canadians,” pro bono legal representation, and he ended up with his arm around Denzel Washington, who proclaimed, “this man is love.”

So, Carter’s stories deserve more scrutiny than they receive from Crossman and Hammer.

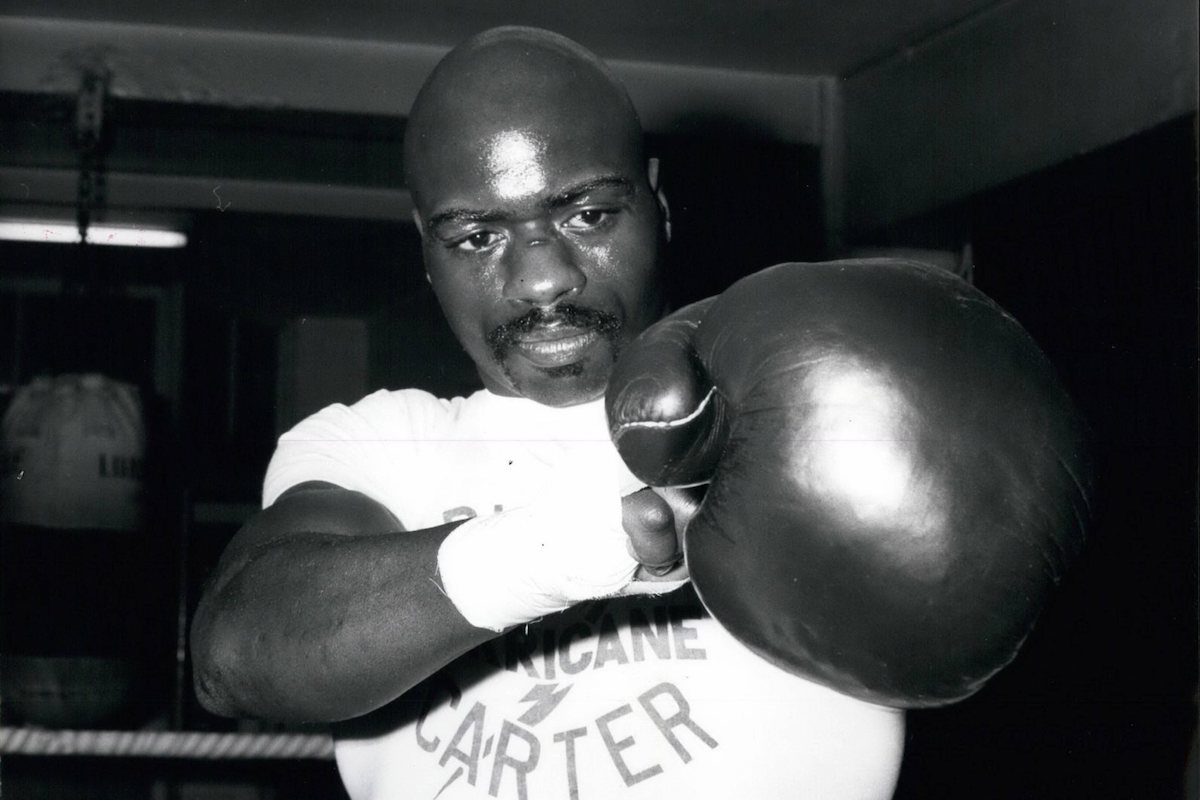

Rubin “Hurricane” Carter—the five-foot-seven boxer with the goatee and the shaved head—provided good copy from the time he gave his first interviews to sports reporters as a rising pugilist. He convinced otherwise respectable journalists of a host of preposterous things. His biographer, former New York Times reporter James Hirsch, wrote that young Carter would go to the playground and swing “so high he could flip around completely in full circles.” He knocked out a horse with one punch. He smuggled guns to South Africa to help overthrow apartheid. He told “the Canadians” that he used to toil in the Georgia cotton fields as a child, despite having admitted in his autobiography that he said he never went to the Deep South and never experienced a Jim Crow regime until he joined the army. Hammer and Crossman report that Carter wrote his passionate prison autobiography, The Sixteenth Round, on pieces of toilet paper. Why he had to do this when he already had an agent, an editor, and a contract with Viking Press, is not explained.

All right, so these are the colourful tales of an irrepressible raconteur. But it seems that for journalists, it doesn’t matter how many self-serving stories Carter tells, he remains credible when he says he didn’t kill those three people in the bar. Conversely, it doesn’t matter how many times the lead detective on the case, Vincent DeSimone, told Alfred Bello and other witnesses, “I only want the truth.” His reputation is forever tainted, a fact that causes anguish for his son, who will soon be publishing his father’s memoirs, entitled The Media Meddlers.

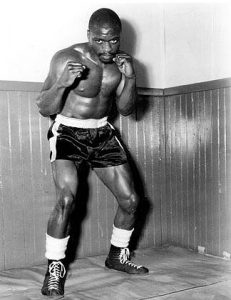

The myth of Rubin Carter includes that Dylan howl of outrage, he coulda been the champion of the world. Not only was he falsely accused and convicted, but he was stripped of everything on the eve of his greatest triumph. This point has been seized upon by journalists, who almost invariably mention it when profiling him. Some have Carter “in the middle of training” for the championship, “about” to challenge, “preparing for a shot,” or “one fight away” from taking on Dick Tiger. One sportswriter rhapsodized that “Rubin Carter was as close to the world middleweight title as he was to the electric chair.” Even Judge Sarokin, whose ruling set Carter free after 19 years, wrote that Carter “was, at 30 years old, reaching the peak of his career, a contender for the middleweight crown…” In reality, by June 1966, Carter had fallen from the rankings, had lost three of his last five fights, was drinking heavily, and made ends meet as a construction laborer. Dick Tiger wasn’t even the middleweight champion at the time.

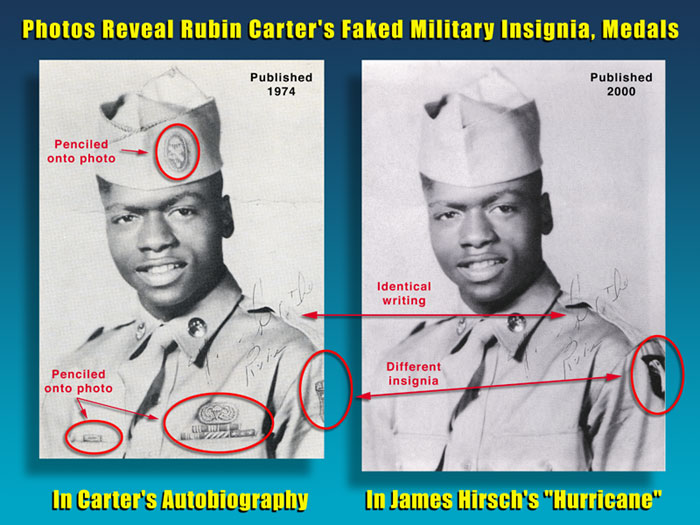

In The Sixteenth Round, Carter portrayed himself as a champion of the weak. In fact, Carter was a bully who was sent to a special behavioral school because his classmates were terrified of him. He lied about why and when he was sent to juvenile detention. He claimed he had been imprisoned at the age of 11 for stabbing a pedophile with a knife. In fact, he was 14 and he’d clubbed a man with a bottle and stolen his watch. He wrote that he ran away, aged 17—the podcast omits the part where he ducked a hailstorm of bullets—and then enlisted in the Army. There is a photo of Carter in his army uniform, covered with ribbons and medals. They were penciled on. Carter won no ribbons or medals.

Crossman and Hammer repeat Carter’s tale about how he joined the army boxing team, and no wonder, because it’s a great story. In its earliest iteration for sports reporters, Carter and a “drinking buddy” noticed his battalion’s boxing team working out and a drunken Carter boasted that he could beat any of them. (In later versions, the drinking buddy is a bearded Sudanese Muslim who wears his hair in long braids wrapped around his head because, um, sure, the Army allowed soldiers to have long braided hair and beards in the 1950s). At any rate, the boxing coach invited him back the next day, and to teach the cocky young soldier a lesson, paired him up against a heavyweight champion named Nelson Glenn. To everyone’s amazement, Carter knocked Glenn to the canvas. Carter claimed that he went on to win 56 bouts and become the Army All-European light-welterweight champion. However, the European edition of Stars & Stripescovered Army sports extensively, and no-where does Private Carter’s name appear for the time he was in Europe. The light-welterweight champions for 1955 and 1956 were Al Berry and Gerald Wells, respectively.

In reality, Private R. Carter was court martialed four times in 21 months and the Army dumped him back Stateside. He was soon back behind bars for stealing gasoline (as the podcast recounts). The prison superintendent, a “Mr. Goodman,” promised to look into why Carter had been incarcerated without the correct paperwork. But this faint hope was extinguished when Goodman was promoted to Trenton State Prison. Goodman may or may not have agreed to check Carter’s paperwork, but when he later encountered Carter at Trenton State Prison where he had been sent for mugging two men and a woman, Goodman was one of many prison officials who recommended against parole for Carter and described him in the severest possible terms as a menace to society.

Carter has said various things about his mugging spree over the years, including that it was an impulsive act, a foolish act, a drunken act, and he has also denied he mugged anybody. In the Eye of the Hurricane, Carter blames the violent attacks on his grief over the death of a cousin. It is peculiar that he would portray himself as someone who lashes out violently at innocent people when someone he cares about dies, considering what happened on the night of June 16, 1966.

In prison, Carter was reunited with some of his comrades from his days in juvenile detention.In The Sixteenth Round, he wrote about the moment he learned that their ranks had been thinned somewhat by the electric chair:

“A few months after you escaped from the ‘Burg, Rube…” [his old rival Hobo told him] “the cops… accused Harry and Albert [Wise] and Alfred Stokes of stickin’ up a fur joint and shooting somebody—a police sergeant,” he said. “Everybody we know claims that there were no witnesses to the crime… when it was time for them to die, Harry wanted to be first. But his brother wouldn’t let him. Alfred told Harry that he was the oldest, so he’d go first. He’d pave the way for Harry, and then be waiting for him on the other side.”

Carter was “enveloped in anger” over the loss of his “fast friends,” and “cried like a baby.” “I think I unconsciously made a vow to avenge those beautiful brothers… I wanted to kill the system that had destroyed them…”

However, Carter was not away in the army, but still in juvenile prison when Alfred Stokes and the Wise brothers robbed a dairy farm for its payroll and killed Sgt. Clinton Bond, father of two young sons. There were witnesses, whom the robbers shoved into a closet. After a lengthy trial, the three men were sentenced to death on June 30, 1954—the day before Carter escaped from juvenile detention. Harry was electrocuted before his brother Alfred, not the other way around. They were five to eight years older than Carter, too old to have been in juvenile detention with him. In fact, Harry Wise was serving in the Air Force in Korea at the same time Carter claimed to be befriending him in prison. Carter injected himself into the story of three black men who went to the electric chair, changed a few pertinent details, asserted their innocence, and appointed himself as the one who would avenge them.

This is just a sampling of the biographical falsehoods in The Sixteenth Round.

In 1961, having served his time for the muggings, Carter became a professional boxer and acquired the nickname “Hurricane.” Carter later blamed his managers for sticking him with a “mad dog image” and promoting him as a barely restrained savage fresh out of prison. “I didn’t appreciate it,” he wrote. “I would never say much,” he told interviewer Gerald Colby. “My manager would do all the talking. He was a publicity hound, and he would always bring up my past—that ‘my man was in prison’ stuff. I let it go, and that, I believe now, was a mistake on my part.”

In fact, Carter’s manager Carmine Tedeschi told Sports Illustrated that Carter “was a kitten with a heart of gold.” Tedeschi apologized when Carter hurt a sparring mate, saying, “Maybe it’s the heat, but Carter has a real peeve on today. He’s not that type of young man. Normally, he’s calm and gentle with everybody.” Carter, on the other hand, boasted in an interview with the Saturday Evening Post that he had once joked about shooting at police officers:

During last summer’s Harlem riots, for instance, [Carter] suggested, in jest, to Elwood Tuck, his closest friend, “Let’s get guns and go up there and get us some of those police. I know I can get four or five before they get me. How many can you get?”

At Carter’s 1967 trial, his defense attorney Raymond Brown moved quickly to prevent the prosecution from mentioning the Post article and his client’s violent rhetoric. Carter and Artis were guilty of Driving While Black, nothing more. Carter was a model citizen, while Artis was literally a choir boy. It was only later, after successful black radical autobiographies like Soul on Ice were published, that Carter, stewing angrily in his prison cell, (though not, as he later claimed, stuck in solitary confinement), decided he had been framed for his black activism. Now that joke about shooting cops became the kernel of an elaborate and entirely false scenario laid out in his autobiography and eagerly taken up by a raft of celebrity supporters and journalists.

By 1973, in his reincarnation as a dashiki-wearing radical political prisoner, Carter claimed he had been quoted out of context by the Saturday Evening Post. Of course, he had to misrepresent the quote, as he did in a 1975 Penthouse magazine interview:

I said that black people ought to protect themselves against the invasions of white cops in black neighborhoods—cops who were beating little children down in the streets—and that black people ought to have died in the streets right there if it was necessary to protect their children.

Carter said he was speaking of the Harlem Fruit Stand riot, a fracas in April 1964 during which some black school children were accused of turning over some cartons at a Harlem fruit stand. The police were called and started beating some of the children with nightsticks. Historian Truman Nelson wrote about the Fruit Riot in The Torture of Mothers, published in 1968 [emphasis added]:

How could we, in God’s name, know that this happens and expect these [Harlem] citizens and men to stand by without interceding by word or gesture while little kids not yet in high school are kicked and cuffed and beaten over their heads with clubs until they are bleeding?

Carter evidently plagiarized Nelson’s outrage in The Sixteenth Round and passed it off as his own [emphasis added]:

[T]he terrible violence that swept through the streets of Harlem the afternoon of April 17, indiscriminately striking down little kids who were not yet even of high school age…

hundreds of sadistic policemen arrived on the scene with their pistols drawn, and started kicking and cuffing and beating those little children over the head with their billy clubs until they were lying out in the streets, torn and bleeding like the abused lumps of helpless humanity they were.

Carter complained that from the time the Post article came out, “I was hog-tied and branded as a mad-dog, cop-killing nigger who was hell-bent on wiping out the law—single-handedly, no less.” The BBC podcast repeats his claim that Sugar Ray Robinson called him up and scolded him, “Man, what are you trying to do, get yourself killed or something? Have you got any idea what this article is saying?” But Robinson was in Europe at the time and long-distance phone calls were very expensive in the 1960s.

A review of the Paterson newspapers in those years shows headlines such as: “Carter, Back from Mississippi, Dedicates Self to ‘Carry My Share,’” “Carter to Call Summit Confab of Negro Leaders,” “Carter on Rights March,” “Black Power Objective to Smash System, Not Windows, says Carter,” “Head of CORE in Passaic Held in Dispute with Police,” and “Black Power Preached by Carter at Street Rallies.” But these headlines all refer to Rubin Carter’s cousin, Ed Carter. Who, inexplicably, was not framed for murder. The fact is that Rubin Carter was never a civil rights activist. He never spoke out about civil rights. There are no contemporary photos or news articles showing him doing or saying anything to show his concern for his fellow blacks. None. Since he was a local celebrity, Paterson’s newspapers would have covered him had he taken the slightest interest in the subject.

Not only was “The Man” not out to get Carter, at the time of the murders, Carter was working for “The Man.” The city of Paterson had received some federal dollars to splash around, as race riots were sweeping the country, and Carter was hired as a “Youth Outreach Counsellor” for the city at $2.50 per hour. Nevertheless, thanks to the stories spun in The Sixteenth Roundand elsewhere, Carter assumed the mantle of activist/martyr that is now a firmly established part of his legend. A profile in Maclean’s, the Canadian magazine, epitomizes his ersatz credentials. “Why did the New Jersey authorities pursue Carter with such a vengeance?” journalist Brian D. Johnson asks rhetorically, before answering his own question as follows:

He was a well-known, arrogant black man in a racist community. It was 1966… Race riots were ripping through American cities, and Carter symbolized a threat.

That, apparently, is all the proof any journalist needs to postulate a full scale conspiracy to commit judicial murder—a conspiracy that involved dozens of policemen, prosecutors, judges, two juries, and half-a-dozen newspapers.

Carter’s claim that he was targeted by the cops because of the “shoot some cops” quote is also bogus. Without exception, every incident that he recounts is false. This is not colourful storytelling—this is lying for a purpose. He wrote that after the Post article was published, “I began to feel the heat almost immediately” when he was arrested in Hackensack for “disorderly conduct” and “failure to give good account.” The charges were soon dropped. But the record shows he was picked up in January 16, 1964—eight months before the Post article even came out, a chronology of events which Carter casually reverses in his autobiography.

The next piece of evidence Carter lays before his readers is an arrest for atrocious assault in a nightclub. In Carter’s re-telling, he was, true to form, coming to the aid of a friend, but once he got involved, “the mayor of Paterson… and ninety of his goon-squad policemen were out looking for me.” The assault happened in August, and his victim didn’t press charges until early October, which was, again, before the publication of the Postarticle.

The only run-in which happened after the Post article came out occurred in April 1965 when he was picked up in an illegal after-hours bar. Carter says that he was visiting a friend at five in the morning to discuss business with him, when the cops busted in, accused everyone of illegal gaming, nearly shot Carter when they saw who he was, and hauled him away. Carter reprinted the newspaper article about his arrest in his book but altered it, editing out key details to hide the fact that his friend’s apartment was in fact an unlicensed bar, and his friend, whose bail was 35 times higher than Carter’s, was the real target of the raid. Then he complained about the paper’s “vicious lies.” When Carter appeared before Magistrate Charles Alfano, who must have been a boxing fan, Carter was fined $25 for disorderly conduct. He was the one who had been abusive to the policemen at the scene, not the other way around.

Carter claimed this horrific campaign of harassment constituted a conspiracy that went up to J. Edgar Hoover himself. He says Hoover sent a female agent “with a beautiful ass” to tail him in Los Angeles. Why Hoover needed to track Carter when all he had to do was read the sports pages is not clear, but the FBI did not have female special agents in 1964.

But—then came June, 1966, and the Lafayette Grill murders, which were “a godsend to the cops,” because now at last they could send troublesome, outspoken Carter “to the electric chair!” Carter and his supporters contended that he was pulled over by Officer Theodore Capter in the early morning hours of June 16, 1966, just because they were looking for two black men in a white car. In Paterson that’s just the way things go. But there were three men in the car—Carter, Artis, and a man who was later claimed to be a local barfly, a hopeless drunk. Capter initially let them go.

Less than twenty minutes later, when only Artis and Carter were in the car, Capter stopped them again. This time he was specifically looking for Carter because his car—white, with butterfly tail-lights and out-of-state plates—matched the descriptions given independently by Alfred Bello and Patty Valentine at the crime scene. Carter’s first lawyer, Raymond Brown, did not dispute the point at trial.

Brown: The second time you stopped the car at Broadway and East 18th, what was the posture of the car? Did you have to stop them? Were they being run down?

Capter: They were stopped waiting for the traffic light.

Brown: Nothing unusual?

Capter: No. The only thing, it fit the description that I received at the scene of the crime.

Brown: The description you had was that it was a car and when the brakes were applied it caused the rear lights to light up in a butterfly fashion?

Capter: Yes.

Carter reproduced this dialogue in The Sixteenth Round, except that he deleted his lawyer’s key question: “The description you had was that it was a car and when the brakes were applied it caused the rear lights to light up in a butterfly fashion?” The version given to Bob Dylan and Mohammad Ali in a bid to win their support reads like this:

“…The second time you stopped the car at Broadway and East 18th,” Brown asked, “did you have to stop them? Were they being run down?”

“They were stopped [while] waiting for a traffic light,” Capter answered.

“Nothing unusual?”

“No,” the sergeant answered. “The only thing [with two black males in it now,] it fit the description that I received at the scene of the crime.”

Subsequently, Carter’s supporters—including his biographer James Hirsch—have written that Capter said, “Awww, shit. Hurricane. I didn’t know it was you,” when he stopped Carter’s car the second time. That too is a lie. And as for the man with one dying eye, who said he ain’t the guy (Willie Marins, the sole survivor of the shootings), he lived to testify at trial. He said he didn’t know who the shooters were. It had happened so quickly and he’d taken a bullet to the head.

Carter testified that at the exact time of the murders, he was giving two women a ride home. As he humbly explained in The Sixteenth Round, “I had decided that no matter how high I flew in my career, or to what heights I scaled, I would never get too big to remember my people.”

“And they needed a ride to go three blocks?” Prosecutor Vincent Hull asked, gesturing to a diagram of the neighborhood around the Nite Spot.

“Well, this is a real dark area. This is a real dark area here,” Carter answered, meaning the street was not well lit.

“You didn’t even tell the Grand Jury you had taken these two women home, did you?”

“No, sir, I hadn’t.”

When John Artis took the stand during the first trial, he also had trouble explaining why he had given such confused and varied accounts of what he’d done and where he’d been that evening, first to Detective DeSimone and then to the Grand Jury. But still, Artis would have been much better off if he had asked for a separate trial and testified that he’d got behind the wheel of Carter’s car at 2:30 in the morning, but that he had no idea what Carter was doing before that. Although Artis was driving Carter’s car on the night of the murders, he was never anything but a hapless passenger during the legal ordeal that followed.

The BBC’s Crossman and Hammer did uncover some unsettling information about the prosecution—for example, retired Detective Robert Mohl volunteered, with a laugh, that he once knocked Alfred Bello out cold to show him who was in charge. And they fault the prosecution’s reliance on Bello, an almost comically inept petty thief. But Bello had undeniably been in the Lafayette immediately after the murders, and there was very little other evidence available. The bar had no security cameras. There were no cameras at intersections to snap a picture of a speeding car. There was no such thing as DNA testing. There was no crack forensic CSI team. Ambulances didn’t have paramedics. Hazel Tanis and Willie Marins were scooped up and taken to hospital in the long low station wagon that most people would recognize now as the Ghostbusters mobile. Nobody had a cell phone. And men and women often wore hats. The two black assailants were described as being “well-dressed.” John Artis was wearing a smart straw fedora when he went out dancing that night.

Hazel Tanis lived long enough to give a description of her assailant, the one who emptied his pistol into her breasts, her stomach, and her groin, to a police sketch artist.

But the police were not allowed to enter her statement into evidence because it was not taken as a “dying declaration”—that is, Detective DeSimone did not want to tell her that she was dying, which would have been the only way she could have been allowed to give testimony which was beyond the reach of cross-examination. It was an incompetent bunch of conspirators, if conspiracy there was, who would throw away the chance to introduce Tanis’s description of the moment she looked into the killer’s eyes and pleaded for her life. The all-white police conspiracy also dropped the ball when they declined to press criminal charges against Carter for beating a black female supporter, despite her accusation that he kicked her into unconsciousness while he was on bail in 1976 following an argument about a hotel bill.

Every aspect of the case, every witness statement, and every piece of evidence—such as the ammunition found in Carter’s car—was aggressively disputed by Carter’s various attorneys, for years and then decades. His friends the Canadians sincerely believed that there was a plot to frame Carter and wrote that they even began to doubt whether the murders had actually occurred!

The podcast series focusses on the accusation that the prosecution didn’t investigate Eddie Rawls more aggressively. Rawls was a friend of Rubin Carter, and a bartender at the Nite Spot, Carter’s favourite hangout. Rawls was also the stepson of Roy Holloway, the murdered black bartender. Even though the white man who killed Holloway was taken into custody at the murder scene, Rawls stormed down to the police station and demanded that the police “do something,” or he would. This was shortly before Lafayette Grill murders. Rawls failed a lie detector test on the night of the murders, but he was, after all, in an emotional state. He testified before the first grand jury less than two weeks later, then refused to speak to police.

Crossman and Hammer interviewed a retired New Jersey politician, Eldridge Hawkins, who claimed there was no evidence that the police had investigated Rawls—“what I found was such a blight on the criminal justice system”—and he is now writing a book about the case. But the prosecution always saw Rawls as an unindicted co-conspirator. At the Grand Jury hearing, Artis was asked if he had gone to Eddie Rawls’s home on the night of the murders, which indicates Paterson officials were already testing the hypothesis that Rawls’s apartment was where the guns and any blood-spattered clothing was dumped. Artis denied going there. Artis was asked if he knew Eddie Rawls.

A: Yes.

Q: Is Eddie Rawls a friend of yours?

A: A friend? You could call him a friend.

During the podcast, Steve Crossman asks Artis, “Who was Eddie Rawls?” Artis answers, “[Rawls] knew Rubin… but I didn’t know Eddie Rawls… He was a hot head, he was a touch-off.” Rubin Carter’s cousin Johnny Carter, also participating in the interview, coyly suggests that Eddie Rawls confessed to the murders on his deathbed.

If Crossman expected Artis to seize upon the suggestion that here at last was the proof of his innocence, he must have been disappointed when Artis barely reacted. Artis says little in the interview; he just laughs his deep, cigarette-varnished laugh. “If I were you, John,” Crossman says, “and someone had convicted me of murder, and I knew I didn’t do it, I would be desperately trying to find out who it was—I can’t imagine.” “I don’t care who did it. That’s their (the police’s) job,” says Artis. “Hawkins has a theory,” Crossman persists, “in which there were many people involved.” (Yes, he does, and two of those “many people” were Carter and Artis.)

Artis doesn’t say so, but of course he has heard all of this many times before during the protracted legal battle. He and Johnny Carter signal that they are not interested in pursuing this line of enquiry. They tell Crossman that the police were uninterested in establishing the truth, so it was pointless to try to search for it.

Crossman presses on. “Does the name Annie Haggins mean anything to you?… Oh. That’s the biggest eyeroll I’ve ever seen you do.” (Annie Ruth Haggins was never called to testify by the prosecution or the defense. During the investigation, she gave ever-changing versions of stories about the killings. She even said she was in the bar at the time of the shootings. But rather than using Haggins to try and raise reasonable doubt, the defense appeared to hold her in even greater contempt than Detective DeSimone, who concluded she was a crazy publicity-seeker. Ron Marmo, a lawyer on the prosecution team, also found Haggins too unreliable to use as a witness.)

Crossman persists with his questions, naming more of Carter’s associates. “What is your motivation? What are you trying to accomplish?” Johnny Carter suddenly demands. “I’d like to know what happened,” said Crossman. “That’s it.” “We’re not concerned about that,” answers Johnny Carter, suddenly channeling his dead cousin’s spirit. “Because it has nothing to do with us. We were innocent. The hell with who did it. We know we didn’t.” Crossman sounds a little baffled and deflated at their non-reaction and their evident indifference to uncovering the truth.

What should have been obvious to Crossman and Hammer is that neither the prosecution nor the defense needed Hawkins—or two BBC reporters—to explain to them that Rawls, the hot-headed stepson of the murdered black bartender, was a likely suspect. This was evident from the beginning. Prosector Marmo explains to Crossman that “there was nothing to put [Rawls] at the scene… so we couldn’t charge him… he could very likely have been involved and been an accessory…we can’t prove it.” But Crossman continues to insist that the prosecution “ignored” Rawls.

Crossman concludes the series by faulting the defense for not “investigating” Eddie Rawls: “It was in the defense’s interest to look into Rawls too, and there is no evidence that they did.” It is difficult to know how to respond to such naivete. The obvious answer is that Carter and Artis knew all about the role Rawls had played in the murders, and they did not want Rawls to explain what role they had played. Carter and Artis were unlucky enough to be caught, thanks to Patty Valentine’s description of the getaway car. Eddie Rawls was not caught, but the police went so far as to dig up his stepfather’s casket to check if he had hidden the murder weapons in there. But Eddie Rawls is not mentioned by Hurricane Carter in either one of his autobiographies. Nor is he mentioned, not even once, in the Canadians’ book, Lazarus and the Hurricane, although they claim to have spent years and a million dollars chasing down every possible lead and witness in the case.

Once distanced from the Rawls connection, defense lawyers Myron Beldock and Lewis Steel argued there was no reason for Carter to have avenged the murder of Rawls’s stepfather, a man he barely knew. After losing the second trial, the defense then appealed to Judge Sarokin, who agreed that Carter could have had no motive whatsoever to kill a white bartender in revenge for the slaying of a black one, and it was inflammatory and racist to make such a suggestion to the jury. The verdicts of the second trial were overturned and New Jersey decided not to stage a third trial.

Bear in mind that our BBC reporters do not share the tender sensibilities of Judge Sarokin. They believe that the racial revenge motive was plausible, and so did some of Paterson’s more disreputable elements on the murder night. In his grand jury testimony, Artis said that while he was nursing a large Coke in a nightclub, waiting for Carter, “two guys passed and said that they ought to kill every white person in this town.”

Rubin Carter said of himself in The Sixteenth Round, “I wanted to be the Administrator of Justice, the Revealer of Truth, the Inflictor of all Retribution.” Although it was heinous to suggest that a black man would commit a hate crime, the defense attorneys frequently and contemptuously described the white establishment of Paterson as being so racist, so eager to avenge the murders of three of their own, so bent on sending two black men to the electric chair, that their clients could never get a fair trial. And the all-white jury agreed! Tribal hate, tribal vengeance, were easily and readily attributed to the jurors.

The preceding is not a complete survey of the podcast series, or the Lafayette Grill case. It is an attempt to clear up some falsehoods—falsehoods which were repeated in Rubin Carter’s New York Times obituary. Imprisoned at 11. Army Boxing Champ. Targeted by the police. Coulda been the champion of the world.

But myth is more powerful and potent than the facts. The emotional resonance of “innocent black man, on the verge of winning middleweight crown, framed for murder” is irresistible to those already convinced by the meta-narrative of American racial injustice the Carter myth served. The facts of a complicated case cannot compete with a cry for justice wafted to the skies by a haunting gypsy violin.