Communism

Milan Kundera Warned Us About Historical Amnesia. Now It's Happening Again

Conflict-induced-apathy can be manipulated for political ends.

The struggle of man against power is the struggle of memory against forgetting.

—Milan Kundera

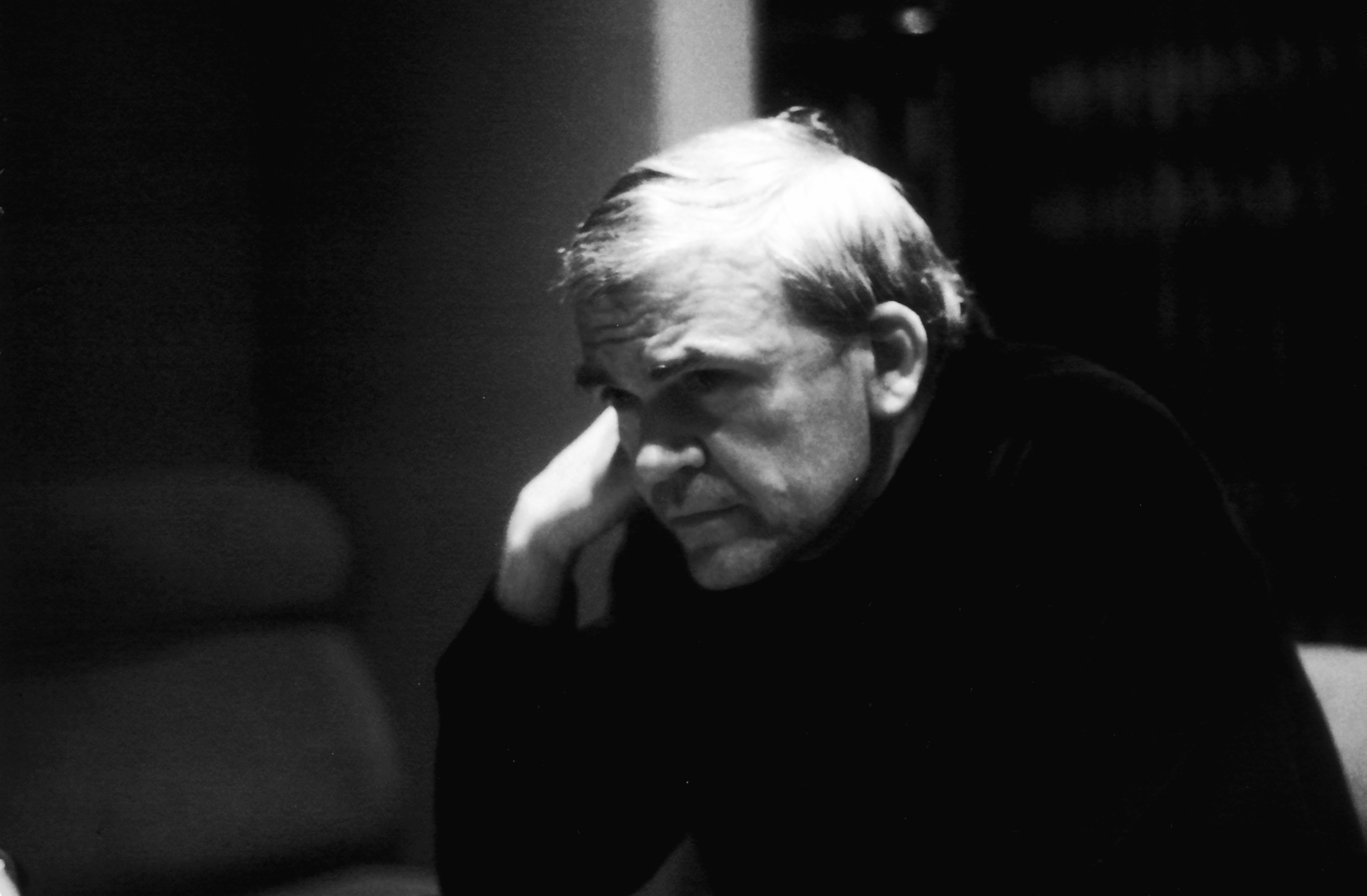

Milan Kundera is 90-years old on April 1, 2019 and his central subject—The Power of Forgetting, or historical amnesia—could not be more relevant. Kundera’s great theme emerged from his experience of the annexation of his former homeland Czechoslovakia by the Soviets in 1948 and the process of deliberate historical erasure imposed by the communist regime on the Czechs.

As Kundera said:

The first step in liquidating a people is to erase its memory. Destroy its books, its culture, its history. Then have somebody write new books, manufacture a new culture, invent a new history. Before long that nation will begin to forget what it is and what it was. The world around it will forget even faster.

I first read Kundera’s Book of Laughter and Forgetting (1979) back in 1987, when I was a member of the British Communist Party. The book shook my beliefs and Kundera’s writing became a part of a process of truth-speaking that shook the USSR to the ground in 1989.

In the 90s we believed we were living in a “post-mortem” era in which all the hidden graves of the 20th century would be exposed, the atrocities analyzed, the lessons learned. Lest we forget. We also thought we’d entered a time in which the Silicon Valley dream of digitizing all knowledge from the entire history of the printed and spoken word would lead us towards the infinite free library, the glass house of truth and the global village of free information flow. The future would be a time of endless remembrance and of great learning.

How wrong we were. The metaphor of the glass house has turned into that of the mirrored cube. The global village has collapsed into tribal info-warfare and the infinite library is now a war zone of battling conspiracy theories. The internet has become a tool of forgetting, not remembrance and the greatest area of amnesia is the subject that Milan Kundera spent his entire life trying to preserve, namely the horrors of communism.

This theme is set out on the very first page of the Book of Laughter and Forgetting in which Kundera describes a moment in Prague in 1948 amidst heavy snow in which the bareheaded Communist leader Klement Gottwald, while giving a speech in Wenceslas Square, was given a hat by his comrade Clemetis:

Four years later Clemetis was charged with treason and hanged. The Propaganda section immediately airbrushed him out of the history and obviously the photographs as well. Ever since Gottwald has stood on that balcony alone. Where Clemetis once stood, there is only bare wall. All that remains of Clemetis is the cap on Gottwald’s head.

After the fall of the USSR, there was a vast outpouring of truth-telling about the fallen communist regimes in Russia, Czechoslovakia, East Germany, Bulgaria, Hungary, Albania, Romania and Poland. The stagnant debt and corruption, the human rights abuses in political-prisons and orphanages, the hidden mass graves, the illegal human experiments, the secret surveillance systems, the assassinations, the mass starvations, and the overwhelming evidence of the failure in each country of “the planned economy.” The structures, too, of government-misinformation, the eradication of free speech and the re-writing of history—erasing your opponents by murdering them and then wiping all traces of their existence from the history books. In the 90s the hidden data from Stalin’s famine-genocide in the Ukraine (1923–33) was exposed. Later, the scale of Chairman Mao’s genocides staggered the world. Even the methods that communist regimes used to produce historical amnesia were exposed.

For a brief period, the consensus was that the communist experiment had failed. Never again, said the postmodernists and historians. Never again, said the economists and political parties. Never again said the people of former communist countries. Never again.

Fast forward 20 years and never again has been forgotten. The Wall Street Journal in 2016 asked: “Is Communism Cool? Ask a Millennial.” Last year MIT Press published Communism for Kids and Teen Vogue ran an excited apologia for Communism. Tablet announced, with some concern, a “Cool Kid Communist Comeback.” On Twitter, there is new trend of people giving themselves communist-themed names: “Gothicommunist,” “Trans-Communist,” “Commie-Bitch,” “Eco-Communist.” The hammer and sickle flag has been re-appearing on campuses, at protests and on social media.

How could we have forgotten?

A poll in the UK by The New Culture Forum from 2015 showed that 70 percent of British people under the age of 24 had never heard of Chinese communist leader Mao Tse-Tung, while out of the 30 percent who had heard of him, 10 percent did not associate him with crimes against humanity. Chairman Mao’s communist regime was responsible for the deaths of between 30 to 70 million Chinese, making him the biggest genocidal killer of the 20th century, above Stalin and Hitler.

One of the reasons Mao’s genocides are not widely known about is because they are complex and covered two periods over a total of seven years. Information on the internet tends to be reduced into fast-read simplified narratives. If any facts are under dispute we have a tendency to shrug and dismiss the entire issue. So it is precisely the ambiguity over whether Mao’s Communist Party was responsible for 30, 50 or 70 million deaths that leads to internet users giving up on the subject.

The rational way of dealing with clashing estimates would be to look at the two poles. To say, at the bare minimum, even according to pro-communist sources, Mao was responsible for 30 million deaths and at the other extreme, from the most anti-communist sources, the number is 70 million. So it would be reasonable to conclude that the truth lies somewhere in between and that even if we were to take the lowest number it is still greater than the deaths caused by Stalin and Hitler.

However, this reasoning process does not occur. Our reaction when faced with a disputed piece of data like this is similar to our response when faced with a Wikipedia page that carries the warning: “The neutrality of this article is disputed.” Fatigue and lack of trust kicks in. And so, without an argument needing to be made by Mao’s apologists, the number he killed is not zero, but of zero importance.

Conflict-induced-apathy can be manipulated for political ends. We see this in the way neo-communists set out their stall. They don’t challenge the data about the number of 20th Century deaths their ideology is linked to. Rather, they claim that there are conflicting data and that anyone claiming one data set is definitive has a vested interest in saying that—ergo, no data are reliable. And so they manage to airbrush 30–70 million deaths from history.

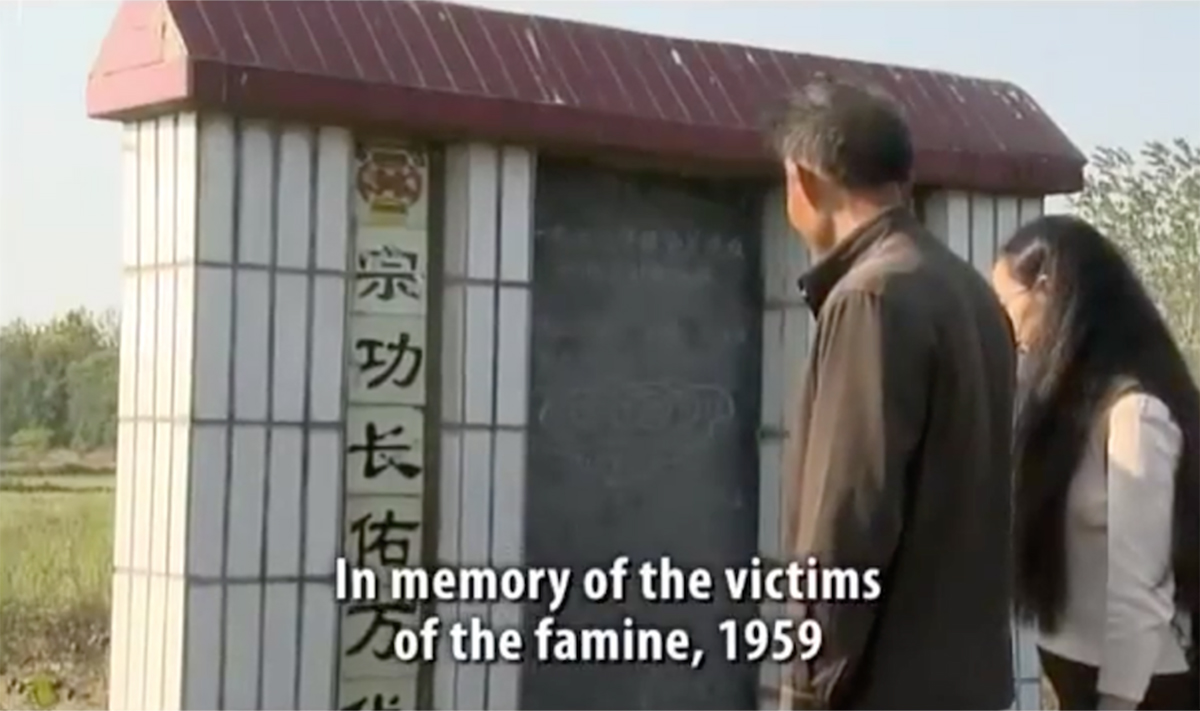

Part of what makes the data on communist genocides hard to pin down is that the state records were often erased by communist regimes. Take the largest genocide in the history of mankind—the Great Chinese Famine (1958–62). To date, no official recognition of this genocide has been made by China’s communist government. For 40 years this historical episode has been hidden and denied. There are 100 monuments to the Irish Famine, but to this day the only memorial to the Great Chinese Famine is one made by hand out of bricks and tiles, located in the middle of a Chinese farmer’s privately-owned field.

Only one memorial to the Great Chinese Famine is one made by hand out of bricks and tiles, located in the middle of a Chinese farmer’s privately-owned field.

Until the data on the deaths in communist China are definitively agreed, until they enter the history books, conflicting data will keep on being used to conceal the magnitude of Mao’s crimes. We also see this happening with the Ukranian genocide known as Holodomor (1932–33). Different political groups argue about whether the deaths were three million or 10, which then gives space to other groups online who want to deny it ever occurred.

If you want to make data vanish these days, don’t try to hide them, just come up with four other bits of data that differ greatly and start a data-fight. This is historical amnesia through information overload.

When we lose not just the data, but the record of who did and said what in history beneath the noise of contrary claims, then we are in trouble. We can even see this in the accusation made against Milan Kundera in the last 10 years—that he was a communist informant, that he was a double agent, that his entire literary canon was the result of a guilty conscience for having betrayed a fellow Czech to the communists.

The confusion and profusion of narratives around Kundera lead us to simply drop the author completely, due to conflict-induced apathy. It has already eroded his reputation. We will never know if what he said in his own defense is true, the argument-from-apathy goes, so we shouldn’t trust anything he’s ever said or written, even his indictments against communism—even his theories about historical amnesia as a communist propaganda tool. All of this might as well be forgotten.

To get rid of an enemy now, you don’t have to prove anything against them. Instead, you use the internet to generate conflicting accusations and contradictory data. You use confusion to elevate hatred and fear until that enemy is either banned from the net, their history re-written or erased from the minds of millions through conflict-induced apathy.

If the struggle of man is the struggle of memory against forgetting, as Kundera said, then we have in the cacophony of the internet a vast machine for forgetting. One that is building a new society upon the shallow, shifting sands of Historical Amnesia.